Why has violent crime declined in Britain?

The decline can be seen in multiple independent datasets. So what are the causes?

Written by Noah Carl.

On Twitter/X, it is common to see large right-wing accounts claiming that violent crime in Britain is out of control based on random videos of people fighting or getting stabbed. The caption to the video will say something like “Modern Britain” or “Sadiq Khan’s London”. Needless to say, this is not a compelling statistical argument. In fact, the best available data show that violent crime is much less frequent now than it was in the late 1990s.

Portable video cameras were rare ten years ago and were almost non-existent twenty years ago. The reason why you didn’t use to see videos of people fighting or getting stabbed is that such incidents weren’t filmed and then broadcast on social media (which also barely existed twenty years ago).

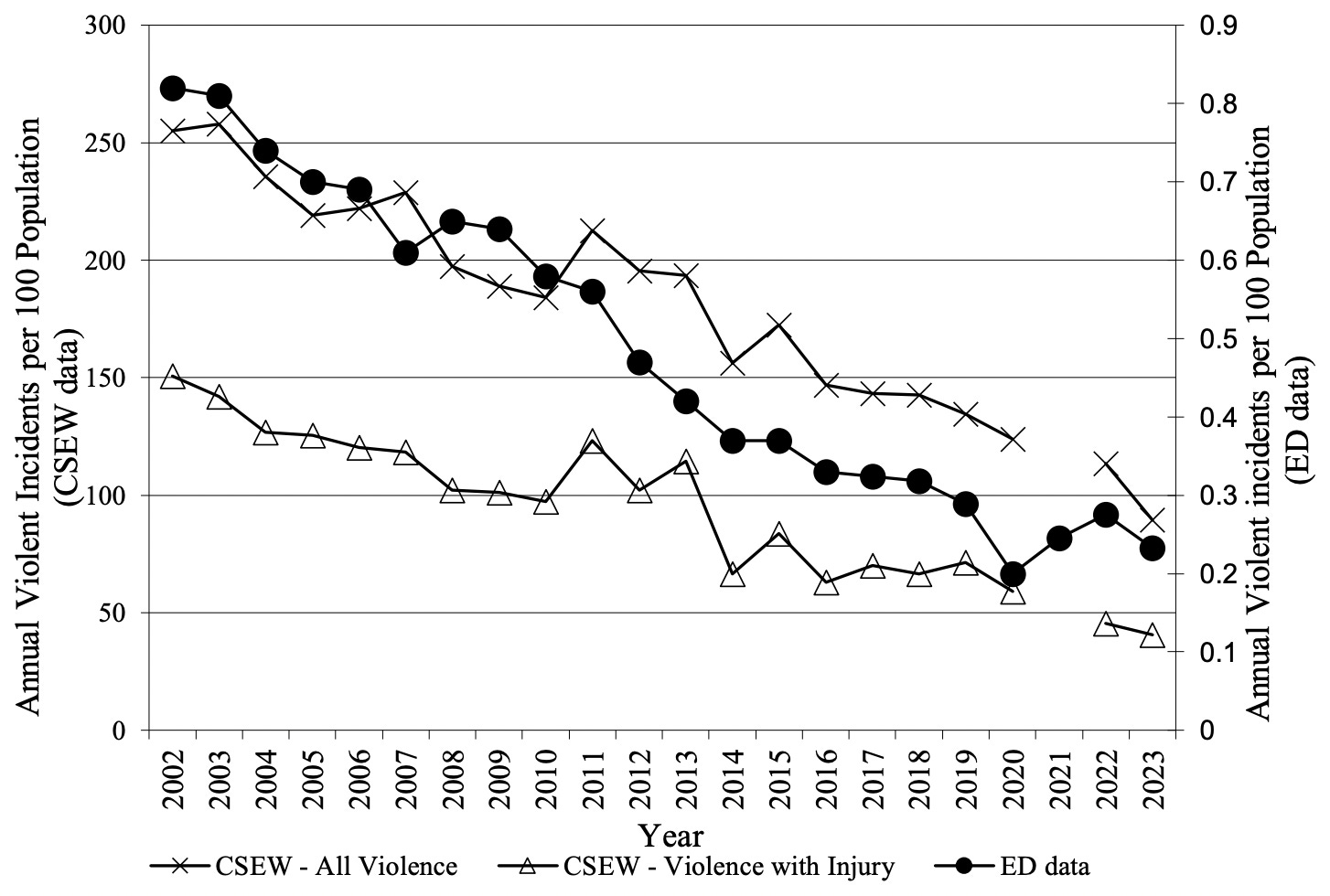

Britain’s violent crime decline is evident in both police-recorded data on homicides and estimates of violent incidents derived from the Crime Survey of England and Wales – as shown below.1

An important caveat regarding the homicide rate is that the spike in 2003 is attributable to the inclusion of 173 victims of serial killer Harold Shipman, who were actually killed at various points over the preceding 25 years. Assigning these murders to their proper years would reduce the value for 2003 but would not change the overall pattern. Indeed, it would raise the values for most or all years before 2003. Note that the value for 2002 is, in any case, the second highest in the series.

What’s more, the uptick in 2017 is attributable to the inclusion of 96 victims of the Hillsborough disaster, who actually died in 1989. (For various reasons, nobody was charged in relation to the incident until 2017.) Assigning these homicides to their proper year would reduce the average homicide rate in the most recent period.

Regarding the rate of violent incidents, there have been some criticisms of the survey on which it is based. Yet so far as I can tell, none of these can explain away the pattern in the data. For example, a methodological change in a single year cannot explain a continuous change over multiple decades.2 It has been claimed that the survey undercounts domestic violence, which may be true, but this is obviously not the type of violence most people have in mind when they think of violent crime.

The rate of violent incidents is derived from a victimisation survey, and it is likely that households whose adult members are criminals would not agree to take part. If violence that only involves individuals from non-participating households (e.g., feuds between rival gangs) is increasing, then the overall violence may have declined by less than official figures suggest. However, I’m not aware of any evidence that this is true, and even if it were, the fact that ordinary people are now much less likely to be victimised is itself important and in need of explanation.

There’s even some evidence that it is false. The decline in violence seen in the Crime Survey of England and Wales is wholly consistent with the decline in admissions to emergency departments for violent injuries. This is shown in the chart below, based on data from a large number of hospitals in England and Wales.

The question, then, is why has violent crime declined?3

Demographic trends

People on the right often assume that crime is out of control for the simple reason that the fraction of the population that is non-White British has increased. Yet they forget that some non-White British groups have low crime rates.

Although Blacks, Albanians and certain other groups commit a lot of crime; Indians, Chinese and Arabs commit very little. And these latter groups have also increased as a share of the population. For example, Indians have an arrest rate of 4.2 (compared to 8.8 for White British), and they have gone from 1.8% of the population in 1991 to 3.3% in 2021. Even Muslims commit crime at only slightly higher rates than White Britons when adjusting for age.

So the net effect of changing ethnic demographics, conditional on other factors, is much less negative than commonly assumed. (This may not be the case in other European countries, where non-Western immigration has been less selective.)

Another relevant demographic trend is population ageing. We know that violence in all societies follows an age-crime curve whereby the vast majority is perpetrated by males between the ages of 15 and 35. It’s therefore germane that the fraction of the population in this age-range decreased by four percentage points between 1991 and 2021. Meanwhile, the fraction older than 60 (a group that perpetrates virtually no violence) increased by three percentage points.

Social and economic trends

One context in which violence often takes place is when people have been drinking. Because inhibitions are lowered and judgement is impaired, trivial altercations are more likely to turn violent. Indeed, a 2016 US study found that 40% of homicide victims had elevated blood alcohol content at the time of their killing.

Hence it is surely relevant that the amount and frequency of drinking has fallen considerably over the last two decades, with the fall being concentrated in the most crime-prone age brackets. According to data from the ONS, the percentage of 16–24 year olds who drank alcohol in the last week fell from 60% in 2005 to 48% in 2017, while the percentage of 25–44 year olds who did so fell from 68% to 54%. Falls in the percentage who drink heavily were even greater.

This trend is driven by the rising non-White share of the population, and likely accounts in part for the “unexpectedly” low crime rates among South Asians and Arabs. The ONS reports that in 2017, 61% of Whites drank alcohol in the last week, compared to only 31% of non-Whites/Other.

Another context in which violence often takes place is during muggings and burglaries. Yet owing to the replacement of cash by debit cards, the falling price of consumer goods, and improved personal security (including window locks and burglar alarms), the expected benefits from mugging someone or burglarising their home have dropped substantially. As a consequence, these crimes have become less common.

In fact, a 2014 study found that the “security hypothesis” was the only one of 17 proposed explanations for the crime drop in Western countries that passed all four evidence-based tests the authors came up with.

One final trend that may be relevant is the decline in lead pollution, as proposed by the famous “lead-crime hypothesis”. While this probably did contribute to the reduction in violent crime, a 2022 meta-analysis detected sizeable publication bias in the literature, such that the true effect of lead pollution is lower than previously claimed. The authors conclude that declining lead pollution in the US can explain about 15% of the homicide reduction between 1976 and 2009.4

Incarceration

When individuals are found guilty of crimes of a sufficiently serious nature, they are put in prison. This reduces crime through two distinct mechanisms: incapacitation (removing crime-prone individuals from the population) and deterrence (raising the expected costs of crime in the minds of prospective criminals). It follows that the crime rate should fall when the incarceration rate rises, other things being equal.

What happened in Britain starting in the mid 1990s? There was a large rise in the incarceration rate. Between 1993 and 2012, it went from 0.09% to 0.15% – an increase of more than 75%. It has since declined slightly, but remains far higher than it was in the mid 1990s. The large rise was brought about by an increase in the number of people sentenced, as well as an increase in the average sentence length. Note that psychiatric hospital detentions also increased over this time period.

Since criminality follows a power law whereby a small number of offenders account for a disproportionate amount of crime, boosting the incarceration rate by 75% should put a sizeable dent in criminal offending. (You only have to imprison a small fraction of the population to pre-empt almost all serious crime – as the case of El Salvador illustrates.) And this appears to be what happened in Britain.

Now, you would expect conservatives to be cheering this rare victory for law-and-order politics. Instead you have them engaging in wild speculation about the unreliability of official crime figures. The appropriate response to the evidence adduced above is to point out that locking up criminals works. But many on the right want to insist that a massive rise in incarceration was actually followed by more violent crime.5

Conclusion

Contrary to the impression you’d get perusing large right-wing Twitter/X accounts, violent crime in Britain is not out of control. In fact, it’s much less frequent now than it was in the late 1990s – a pattern seen in various Western countries. The likely reasons for this decline can be grouped under three major headings: demographic trends; social and economic trends; and incarceration.

Although the non-White British share of the population has gone up, some non-White British groups commit crime at lower rates than White Britons. Meanwhile, the fraction of the population in the most crime-prone age brackets has dropped. Drinking is down, as are muggings and burglaries. And the level of lead pollution has fallen too. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there has been a large rise in incarceration.

Noah Carl is Editor at Aporia.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

To chat with fellow Aporia readers and attend meet-ups, join our Telegram. You can also follow us on Twitter.

For an explanation of why the Crime Survey of England and Wales provides the best available data for many types of crime, see my previous article on the topic.

In order for changes in sampling to explain the pattern, the sample would have to be getting more and more biased towards low-crime areas with each successive year. This is rather implausible.

The decline in violent crime is something that has been documented in various Western countries, and it would be odd if Britain were an exception.

The increased time young men spend playing video games is yet another potential cause of the violent crime decline, with some scholars having argued that gaming acts as a substitute for criminality. However, other scholars have argued the opposite, based on experiments that find gaming prompts aggression. Overall, the evidence seems mixed.

Rising incarceration is thought to be a major reason why crime fell in the US during the 1990s.

Your local soviet insists that more bread was produced this year than in every previous year combined, so you should not fret about the store shelves being empty.

I wonder who is lying, your local soviet, or the store shelves?

This is poor work by Aporia's standards. Specific categories of crime, such as rape, gang activity, and acid attacks, have exploded in frequency across England over the past few years. Go read Licence to Kill by David Fraser.