Written by Arctotherium.

“Immigration is America’s superpower” is a common thought-terminating cliché in US political discourse [1][2][3][4]. Proponents claim that the US can absorb the world’s human capital like a sponge and use it for geopolitical advantage, with many wanting more skilled immigration to “beat China” [1][2][3][4]. Brain drain is conceived as the keystone of a geopolitical strategy to preserve US hegemony and maintain America’s economic edge over other countries. The US can remain the world’s greatest power by opening the gates for as many people as possible, or at least as many above-average people.

Yet there’s an incredible hubris and bizarre lack of respect for immigrants’ agency implicit in this worldview.1 The hubris lies in the belief that the United States is so incredibly amazing that every capable person on Earth wants to be an American. The lack of respect lies in the belief that immigrants and their descendants don’t have their own views on how things should be run.

(I will include this disclaimer, which should not be necessary, at the start to make sure I’m not misunderstood. I am not saying no immigrants to the US are patriotic or truly American. I am saying that brain drain proponents assume this is the case for most or all immigrants for no good reason.)

When I say “geopolitical strategy,” I mean that the aim is to increase America’s power relative to that of other states. In 2025, the only real rival in the world is China, but India2 and a more unified European Union are plausible competitors too, especially if American demographic diversification continues. Unlike economics or science, geopolitics is zero sum: it doesn’t just matter what the United States is capable of, but what the United States is capable of compared to its competitors. Objectively, the USA is far more powerful in 2025 than in 1945, but geopolitically it is much weaker.

When brain drain works: The foreign experts model

It’s not impossible for states to deliberately use brain drain for geopolitical gain. This usually takes the form of what I call the “foreign experts model”. You identify specific areas in which national industry is inferior to foreign counterparts, and then invite small numbers of foreign experts in these areas (often many fewer than 10,000) to come and teach locals their skills, usually by paying them.3 The key components of the foreign expert model are:

It is demographically insignificant.

Foreign experts are expected to transfer their skills and knowledge to native students.

Foreign experts are recognized as foreign. There’s no expectation that they naturalize (though in some cases they do, and because of (1) this doesn’t matter much) and they’re usually excluded from political positions. They may have influence and authority in their domains of expertise, but not over the nation as a whole. This is crucial because giving up control of the state to gain geopolitical power is putting the cart before the horse.

Foreign experts are paid large sums of money or otherwise rewarded (usually above market value) for their expertise.

An illustrative example of the foreign experts model comes from the history of Saudi Aramco. Saudi Arabia has massive and easily-exploitable oil reserves, but did not have the local expertise to drill them after WWII. Relying on a wholly American-operated company would have left the country dependent on American goodwill and with little leverage. Iran and Venezuela chose to destructively nationalize their foreign-operated oil companies, while Equatorial Guinea and Nigeria allow foreign oil companies to operate autonomously in exchange for bribes and payouts. The Saudis took a wiser path:

At the very start of Aramco, the company was entirely owned and operated by Americans aside from menial labor. However, the Saudi government inserted a clause into their contract with the corporation requiring the American oil men to train Saudi citizens for management and engineering jobs. The Americans held up their end of the bargain, and over time, more and more Saudis took over management and technical positions. This steadily increased the bargaining power of the Saudi government, which periodically renegotiated its contract with the Americans over decades to get a greater share of the profits in exchange for more oil exploration or diplomatic concessions.

In 1973 and 1974, the Saudi government authorized two big final buy-outs of Aramco. The prices were not disclosed publicly, but the consensus is that the American oil companies were well-compensated, and that’s after they had made enormous profits for 30 years. This left the oil companies on good terms with the Saudis who were happy to employ them as consultants and specialists. Today, 80% of Aramco’s employees are Saudi, as well as all executives, though surprisingly not all board members.

History is full of similar examples. The English government invited German John Hurdegen to serve as “master of the assays of our mines” in 1545, paying him a salary of 40 pounds per year (approximately 32 times the annual wages of an English laborer at the time) and developed several other mines using German expertise. Small numbers of German engineers, surveyors, and managers brought superior German mining techniques to England, where they taught their skills to locals. Contrast this with the approach favored by Eastern European rulers, who transplanted entire colonies of Germans into their domains for their mining (and other) skills rather than having them teach locals.4

The Russian state under Peter the Great recruited 60 Dutch shipbuilders and around 750 Western European officers, technicians, and academics to found the Russian Navy. While we lack precise information on most of them, one English hydraulic engineer, John Perry, was offered 300 pounds (approximately 60 times the annual cash wages of an English laborer in 1700) plus expenses and bonuses for completed projects, for his service.

Meiji Japan used European and American military and industrial experts to build up their army and economy and colonize Hokkaido. The total number of “hired foreigners” (O-yatoi, a term coming from Yatoi, meaning “person hired temporarily”) was 2,000-3,000, and their combined salaries reached a third of the national budget in 1874. The Japanese government “did not consider it prudent to let them settle in Japan permanently,” and they were replaced by Japanese students once the latter finished training and learning.

The People’s Republic of China pays foreign experts in many fields enormous sums of money to come to China temporarily and share their skills with the Chinese, despite China having the lowest proportion of foreign-born inhabitants on the planet. Consider this description of how the Chinese shipbuilding industry surpassed the previously-dominant South Koreans:

China must have thought, ‘This is the moment.’ They recruited many engineers, and they must have been after things like the design drawings that they kept privately. Chinese shipbuilding companies tried to recruit Korean engineers by offering them ‘annual salary of 300 million won [~$216,000 USD], 2-3 year contracts’ as if it were a formula. They just sucked up the juice and sent them away when the 2-3 year contracts were up.

There is also China’s “thousand talents program,” in which “50-100 foreign experts each year over about 10 years” are recruited to “focus on the needs of China’s economic and social development in key industries and key areas” and are given research subsidies of 4-6 million renminbi in addition to their regular salaries and healthcare/old age benefits.5

Almost every country in the world did this with American experts in the 20th century, when American technology was the most advanced and American industry was by far the most productive. In fact, transplanting American know-how to Western Europe and Japan was an explicit goal of the postwar US government, successfully turning occupied and destroyed dependents into strong allies and economic partners. This did not require mass emigration from America, just small numbers of American experts living abroad, subsidized by the government as part of the Technical Assistance Program (TAP).

America has its own history of taking in small numbers of extraordinarily talented immigrants.6 The two most famous examples are the 1930s exodus of European scientists to the US (where they were extremely important to the Manhattan Project) and Operation Paperclip. Both fit the foreign experts model.

The total number of European scientific emigres in the 1930s, which included such luminaries as Enrico Fermi, John von Neumann, Edward Teller and Albert Einstein, was demographically insignificant—only a few thousand (less than half of the number of illegal immigrants crossing the Mexican border every single day under the Biden Administration). In fact, the 1930s are the only decade in American history with net-negative immigration.

Far from immigration being America’s superpower, the exodus of European scientists shows how it is possible to gain the benefits of extraordinary talent with almost no immigration at all. Although they were not typically recruited by the US government, several private organizations funded their emigration, with the Rockefeller Foundation paying for 303 and the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars paying for 335. Instead of money, the huge incentive offered was safety from the Nazis and the looming war. These scientists helped make US science world-dominant. But US academia did not rely on the products of Germanophone higher education in perpetuity; the new arrivals taught American students their skills.7

Operation Paperclip is an even purer example of the foreign experts model, since it was wholly centralized around the US government. After WWII, around 1,600 German experts in key technologies such as rocketry, most notably Werner von Braun, were rounded up by the US Army and brought to the US. The huge incentive offered in this case was effectively kidnapping; German experts were not given a choice (though I suspect the vast majority preferred living in the US to ending up in a Soviet sharashka, a war crimes trial, or staying in an obliterated Germany). The numbers, again, were demographically insignificant. And instead of continuing to rely on German rocket expertise indefinitely, the new arrivals transferred their knowledge to locals.

Applying the foreign experts model in the US today might involve paying 200 TSMC engineers seven figures to teach Americans how to make semiconductors, not bringing in hundreds of thousands of replacement-level Indian IT workers or Chinese college students. Anyone making analogies to the Manhattan Project or Werner von Braun to justify the latter is wrong.

Modern brain drain to the US

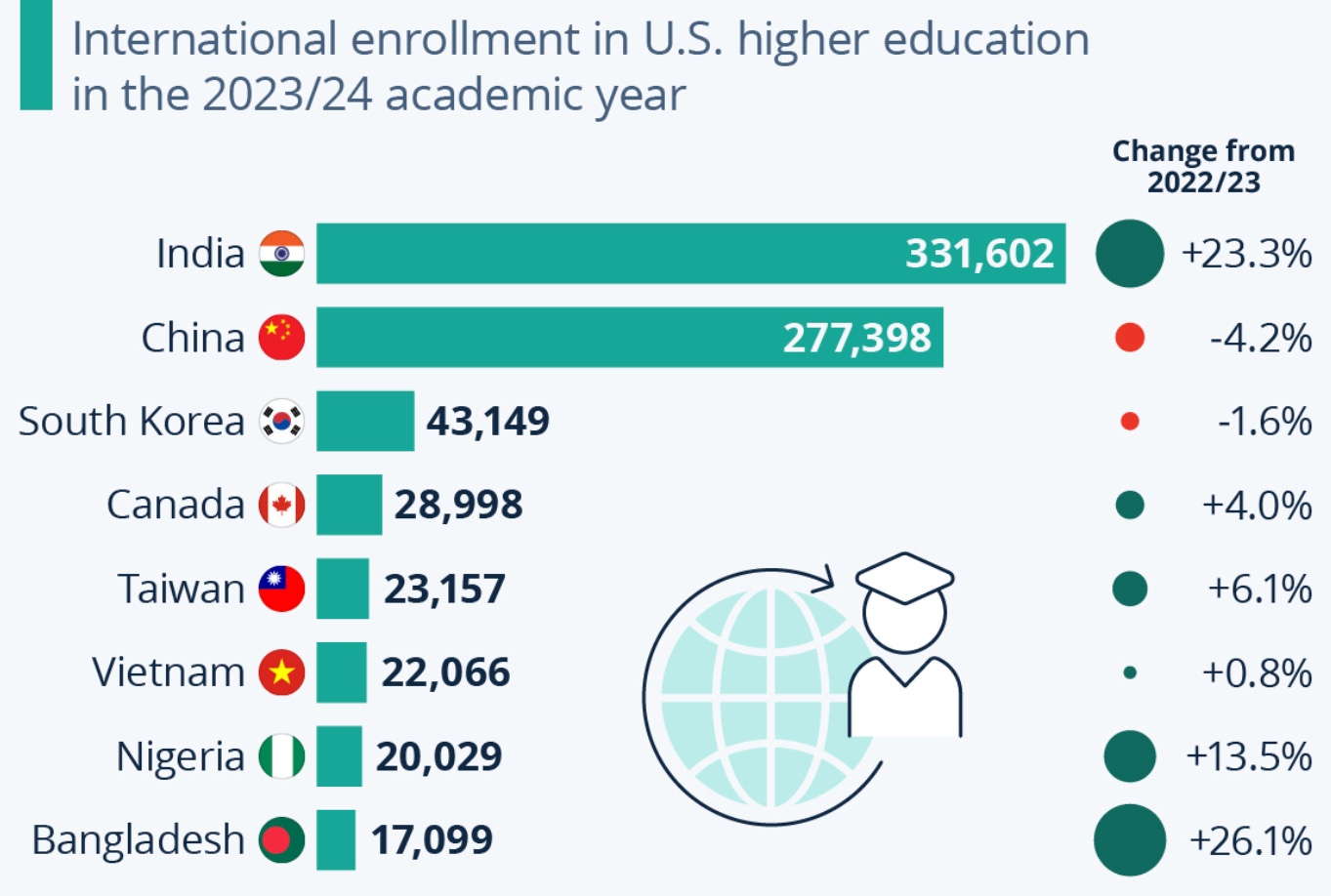

Rather than targeting small numbers of experts for their unique technical skills and presence in superior foreign industries, brain drain to the US today involves bringing in millions of marginally above-average people in the hope that a handful are loyal geniuses. The two major routes are student visas and skilled labor visas such as the H-1B. “America’s superpower” advocates typically want to massively expand both, with proposals such as ending country caps on employment-based green cards, and stapling a green card to every STEM diploma, being common. (Both of these proposals would primarily benefit Indian immigrants, who make up 62% of the green card backlog and 29% of foreign students—not counting secondary migration from Canada, Britain or the UAE).

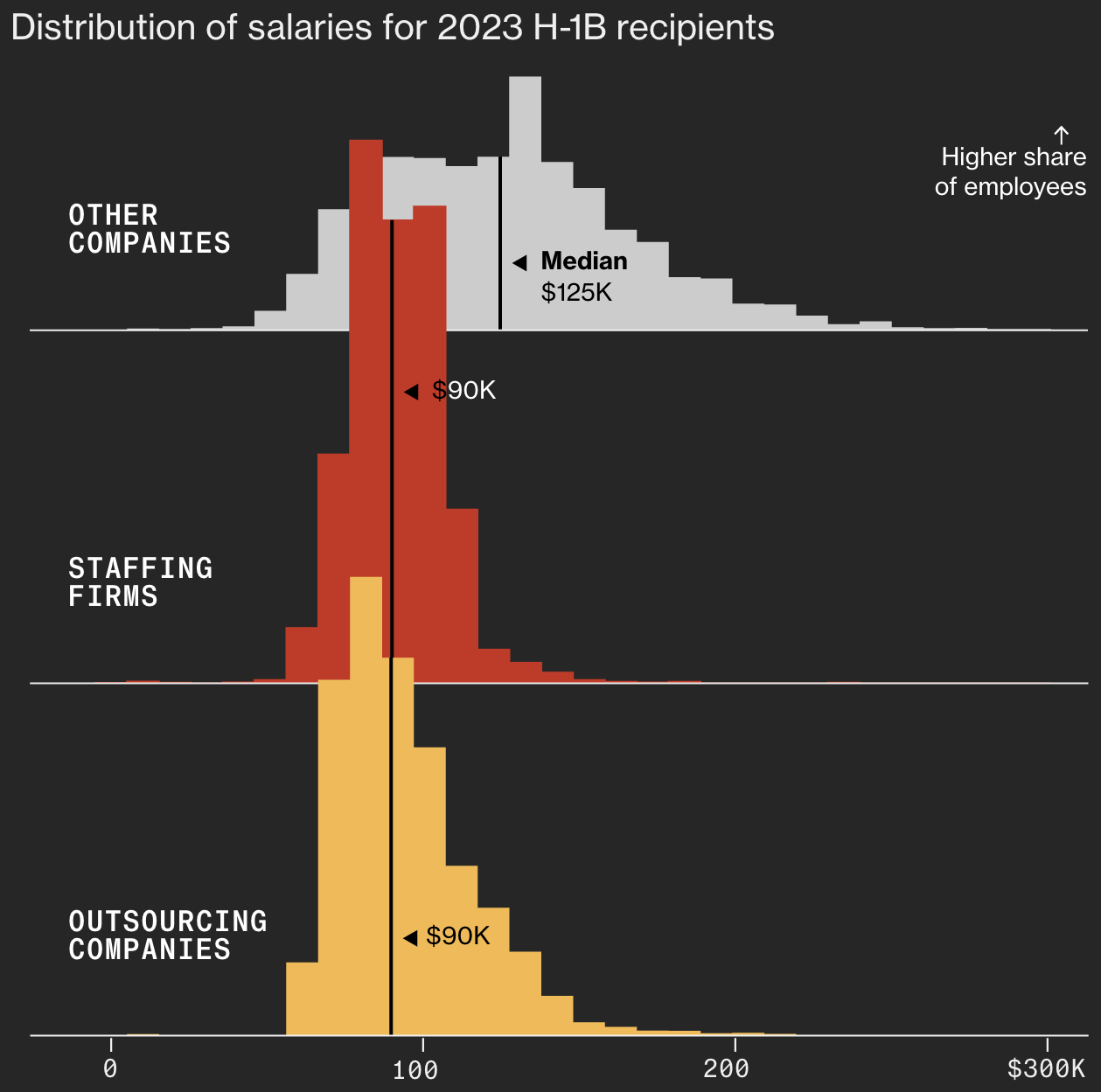

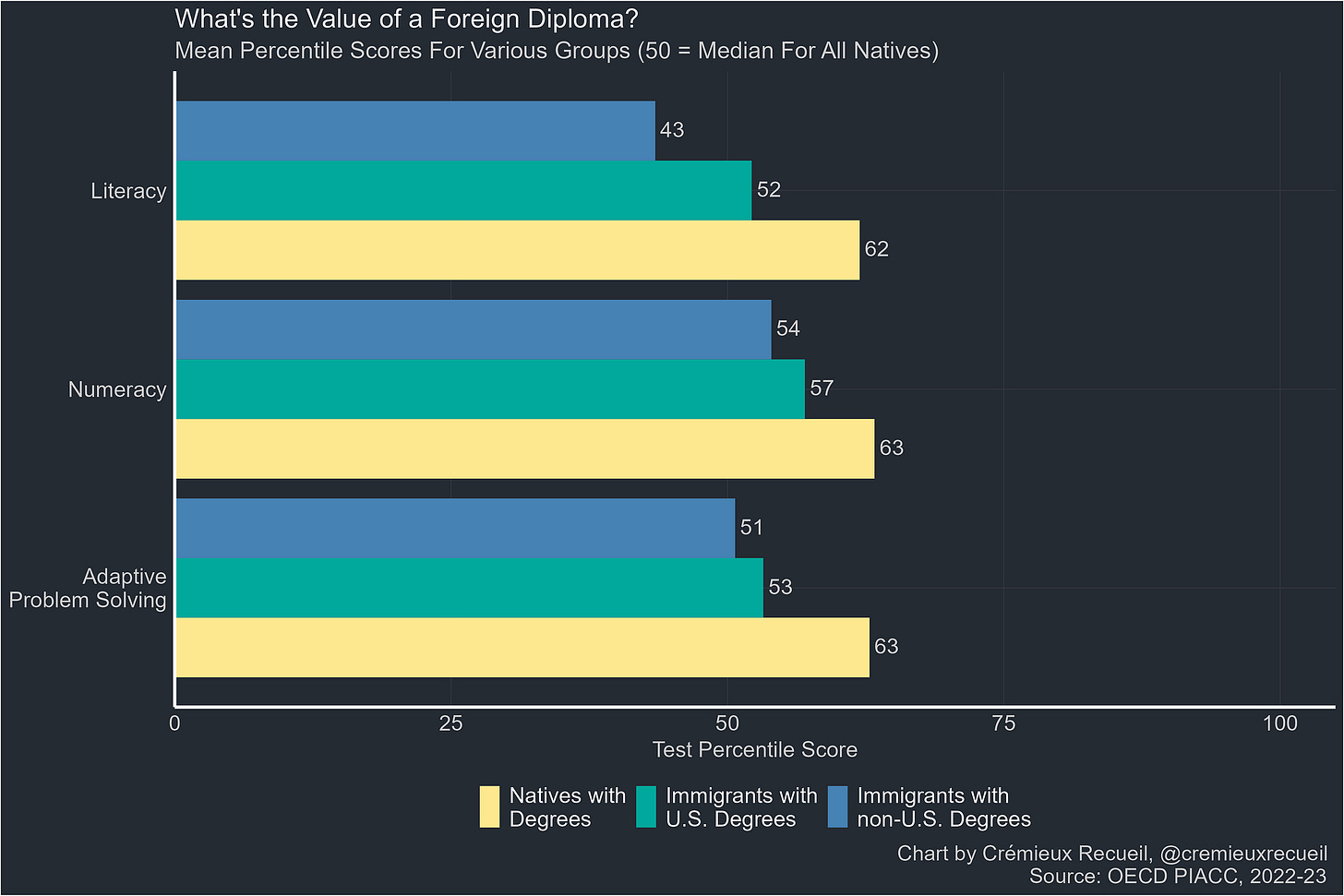

Rather than being an expert in a novel industry or a world-class talent, the typical skilled worker visa recipient is a replacement-level IT worker.

Similarly, foreign-born students with US degrees are barely more literate or numerate than the US average, and they are below the (very low) US-born college-educated average.

When you bring in so many moderately bright people, some are inevitably very successful, like Elon Musk. But this is a nationally self-destructive way of finding them. The combination of ability and numbers guarantees elite replacement and consequent loss of national self-determination. The chief goal of US geostrategy should be allowing the American people to flourish; giving up American control of the US for the sake of geopolitical power defeats the entire purpose.8

Rather than recruiting talent in defiance of the market incentives, 21st century brain drain to the US is driven by said incentives. Skilled immigration to the US does not increase expertise in industries where the US is not already the leader. Instead it has the opposite effect: diffusing US expertise to the rest of the world. Worse, whereas the foreign experts model strengthens domestic sources of talent by providing extremely capable individuals with large spillover effects, modern brain drain to the US undermines the domestic talent pipeline by encouraging wasteful signalling and by forcing competition with the entire rest of the world.

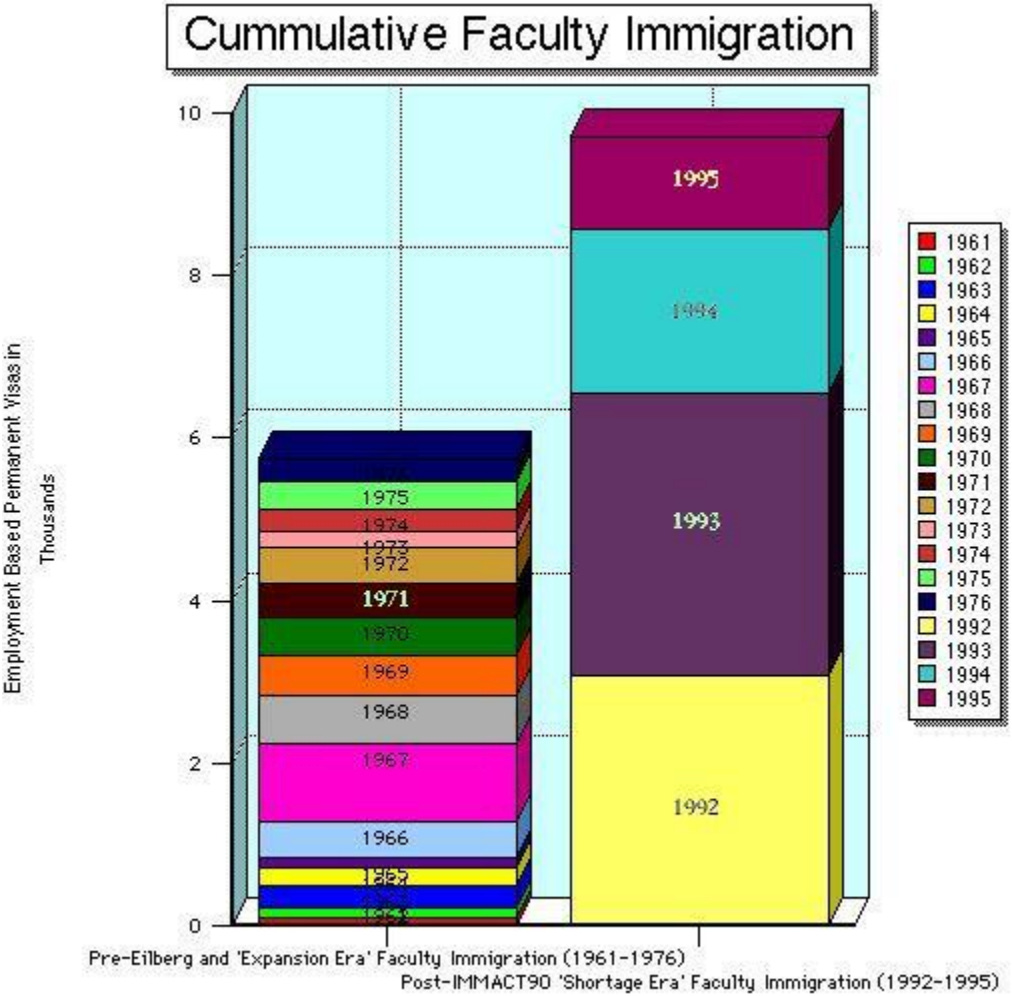

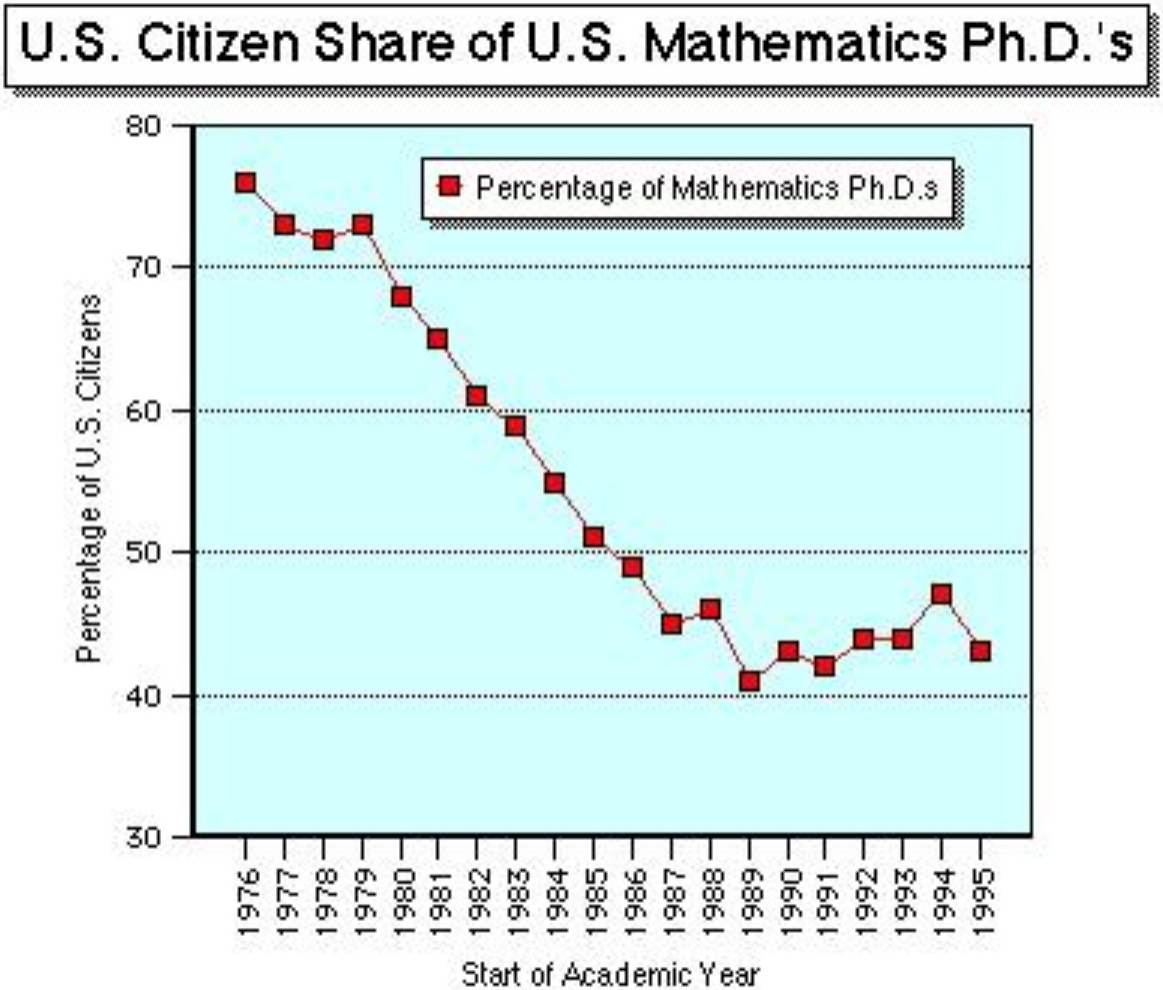

Modern US-style brain drain replacing the foreign experts model is much more recent than commonly understood. US STEM only became thoroughly de-Americanized after the end of the Cold War—for three reasons. First, spending on defence R&D, and with it the protected market guaranteeing a spot for native-born Americans who could be better trusted, was slashed as part of the “peace dividend.” With the Soviet Union gone, there were no plausible military threats to the United States.9 Second, there was a one-time influx of scientists from the former East Bloc, especially the USSR, which interrupted training and credentialing for American STEM scientists in the same fields, squeezing out American researchers. Third, the Immigration Act of 1990 created the H-1B visa.

STEM, unlike fields such as law, finance or business, travels well: the same equations govern radar in the US and China. When combined with immigration, this has the consequence of putting potential American STEM grads (though not specialists in softer fields) in competition with the entire rest of the world. Which, in turn, makes a STEM career more demanding and less rewarding compared to alternatives.

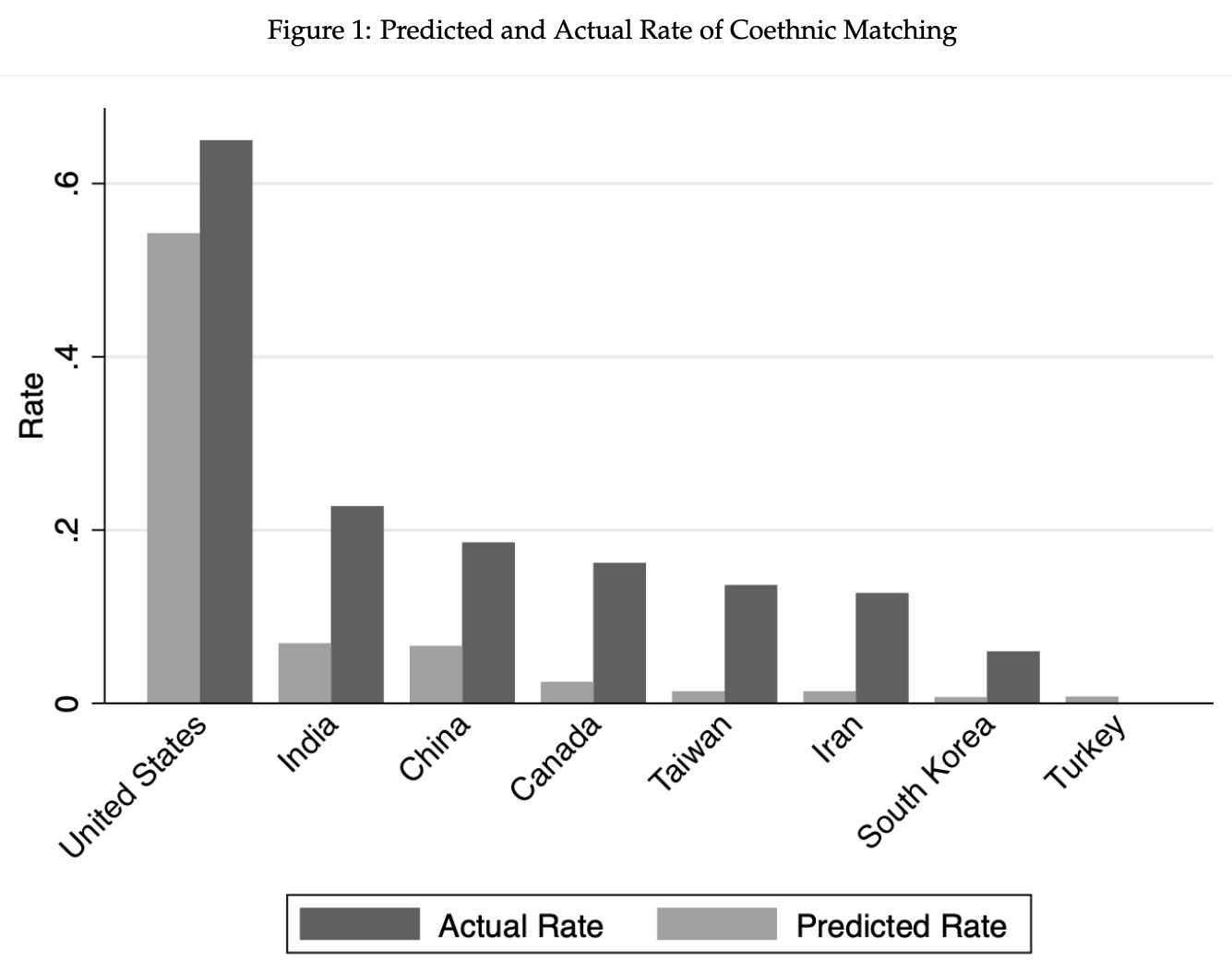

The fact that non-American ethnic groups tend to favor their own in academia makes this worse, with non-American advisors being more likely to mentor, provide internships and industry connections, and otherwise assist their co-ethnics.

Language barriers (many US STEM lecturers cannot speak good English) exacerbate this problem, with the result that many upper-level US STEM programs are now totally dominated by non-Americans, usually Chinese or Indians.

Ideas cross borders easily in the 21st century

The real world is not like a Paradox 4X, where every country has their own tech tree and produces a certain number of research points per turn. Countries that produce very little science in absolute terms, such as Belgium, are not decades or centuries behind the US technologically. This is because ideas and technologies cross borders easily in the 21st century. The fact that a research paper is written or technology is invented within the physical borders of the US does not make it an American technology in the geopolitical sense (with a few minor exceptions). Hence it does not necessarily improve the US geopolitical position. Consider the critically-important steel industry of the late 19th century. The major improvements and discoveries were made in Britain, but were better implemented in Germany and the US. The 21st century-version of steel might be electric vehicles: key technologies were invented in the United States, but they are mostly manufactured by Chinese companies.

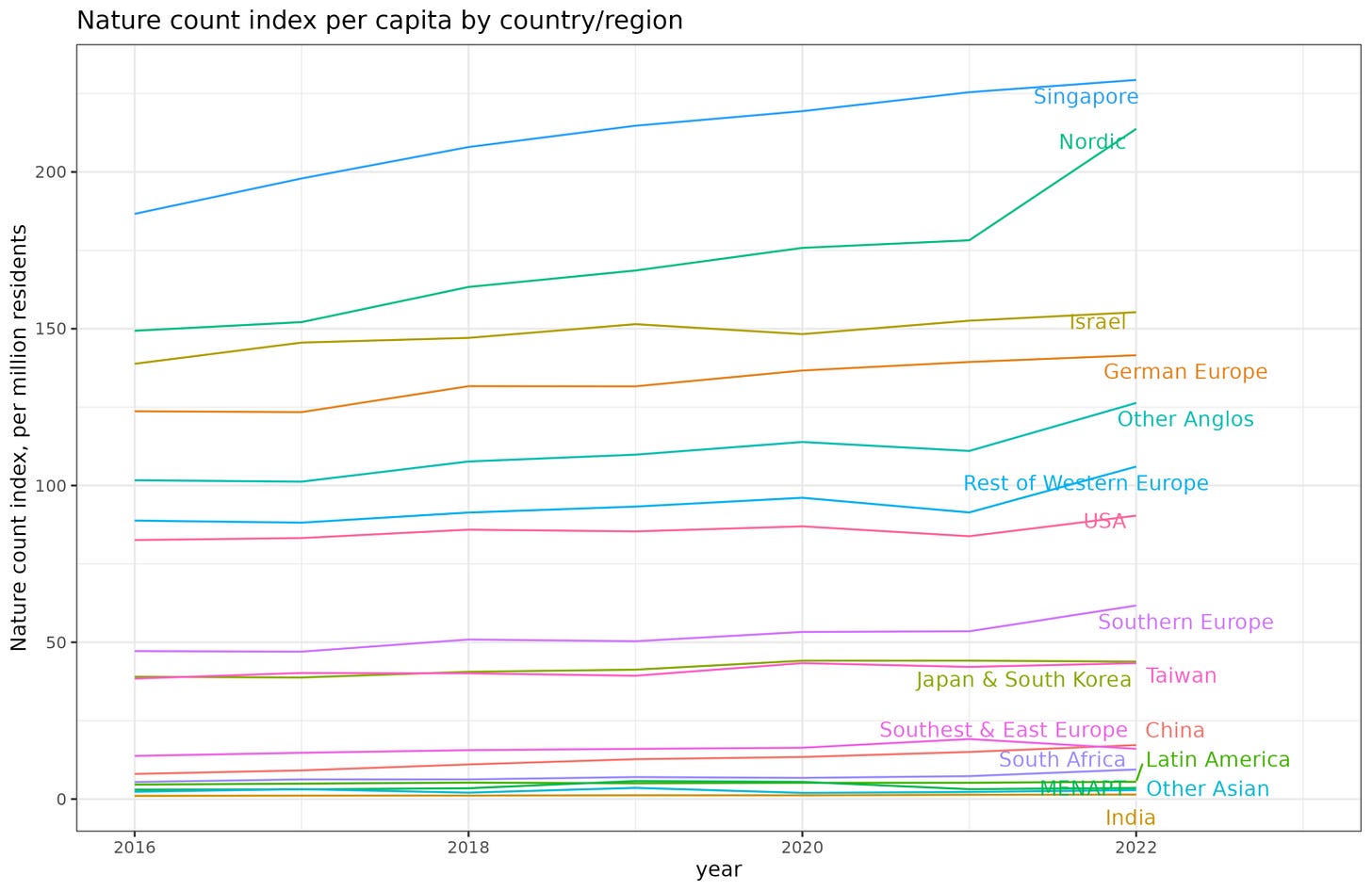

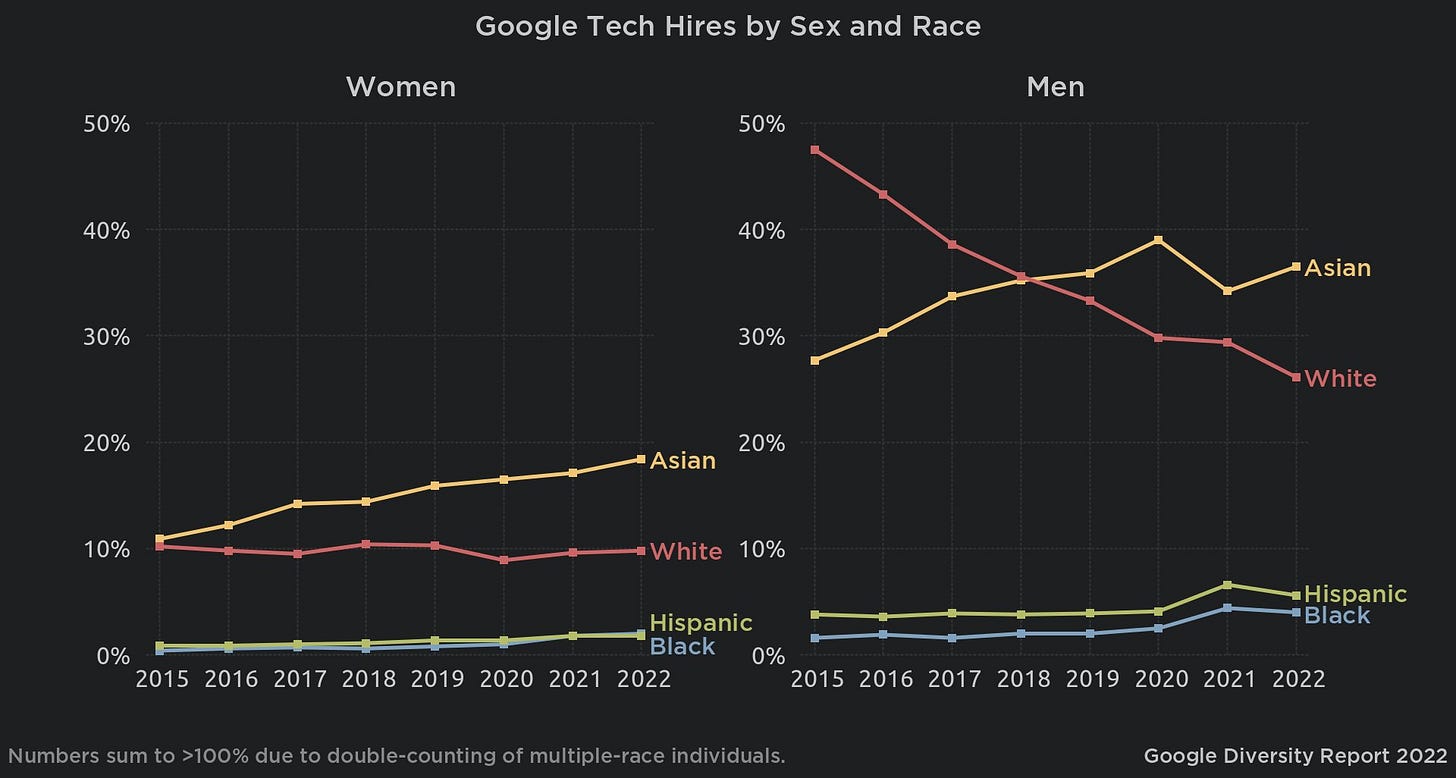

Generally speaking, immigration facilitates the diffusion of ideas across borders. In the US, we are not getting significant numbers of immigrants in fields where the US lags behind, like Korean shipbuilders or Chinese robotics engineers. Instead, skilled immigrants to the US typically come here to work in industries where the US is already the world leader, such as programming. This erodes US leads rather than expanding them: “In surveys of Silicon Valley, 82% of Chinese and Indian immigrant scientists and engineers report exchanging technical information with their respective nations.”

Which is why brain drain boosters who point to the high share of US patents and scientific papers produced by immigrants are barking up the wrong tree: even if the science and innovation physically taking place within US borders is dramatically increased by US-style brain drain (though given the Lotka curve distribution of scientific accomplishment, you could gain the vast majority of this benefit with a tiny fraction of existing skilled immigration), this does not make immigration a strength of the US—because that science and innovation does not stay here.

Mixed loyalties

Many supporters of brain drain as national strategy seem to be missing that patriotism matters. This omission is common among ideas-focused cosmopolitans, but what these people need to understand is that they are abnormal. Just because you don’t care about your nation, state or ethnic group, does not mean everyone else is the same. It takes two to make peace, but only one to make war. Take the Chinese in Australia during the 2019 Hong Kong protests:

Despite being the aggressors in this case, invading protesters’ personal space and menacingly shouting people down, the patriots perpetually framed themselves as victims. Citing an earlier incident in which a group of protesters in Hong Kong threw the Chinese flag into Victoria Harbor, the loudest of the patriots demanded answers from the Melbourne-based protesters for this offense, as if they had personally grabbed the flag from his hands: “Answer my question, are you on the same side as those people who threw our flag into the harbor?” Such accusations and pre-emptive self-victimization in turn provided cover for such blatantly threatening comments from the Chinese students as “We Chinese just want Hong Kong’s land, we don’t care about the people” and “We’ll upload video of this to Weibo, then see if you all are still alive tomorrow.”

In the US, Indians create organizations such as The IndUS Entrepreneurs (TiE), the Wadhwani Foundation, and the Network of Indian Professionals of North America (NetIP) to facilitate ethnic networking (which, by definition, excludes Americans) and often attribute their “conquest” of Silicon Valley10 to a combination of culture and ethnic solidarity (mentoring, investment, networking and so on) [1][2][3][4]. In the words of Vivek Radhwa:1112

Why were Indians so successful?

The first few who cracked the glass ceiling had open discussions about the hurdles they had faced.

They agreed that the key to uplifting their community, and fostering more entrepreneurship in general, was to teach and mentor the next generation of entrepreneurs.

They formed networking organizations to teach others about starting businesses, and to bring people together. These organizations helped to mobilize the information, knowhow, skill, and capital needed to start technology companies. Even the newer associations had several hundred members each, and the more established associations had more than a thousand members.

The first generation of successful entrepreneurs—people like Sun Microsystems co-founder Vinod Khosla–served as visible, vocal, role models and mentors. They also provided seed funding to members of their community.

The Indian networking organizations learned the rules of engagement of Silicon Valley and mastered these. For a while, these were the most vibrant and active professional associations in the region.

Another example is Anupam ‘Tino’ Puri, the first Indian hired at the famous consulting firm McKinsey13, who proceeded to lead white-collar outsourcing from US companies to India and who focussed on hiring and promoting more Indians within the company. Yet another is IBM CEO Arvind Krishna, who has publicly supported Prime Minister Modi’s vision of Atmanirbhar Bharat.

I’m not attacking these people, except insofar as they claim to be American. Ethnic and national loyalties are normal and to be expected. I am attacking fantasists who think that just because someone comes to the US to make money, they are suddenly loyal Americans who are “on our team”.

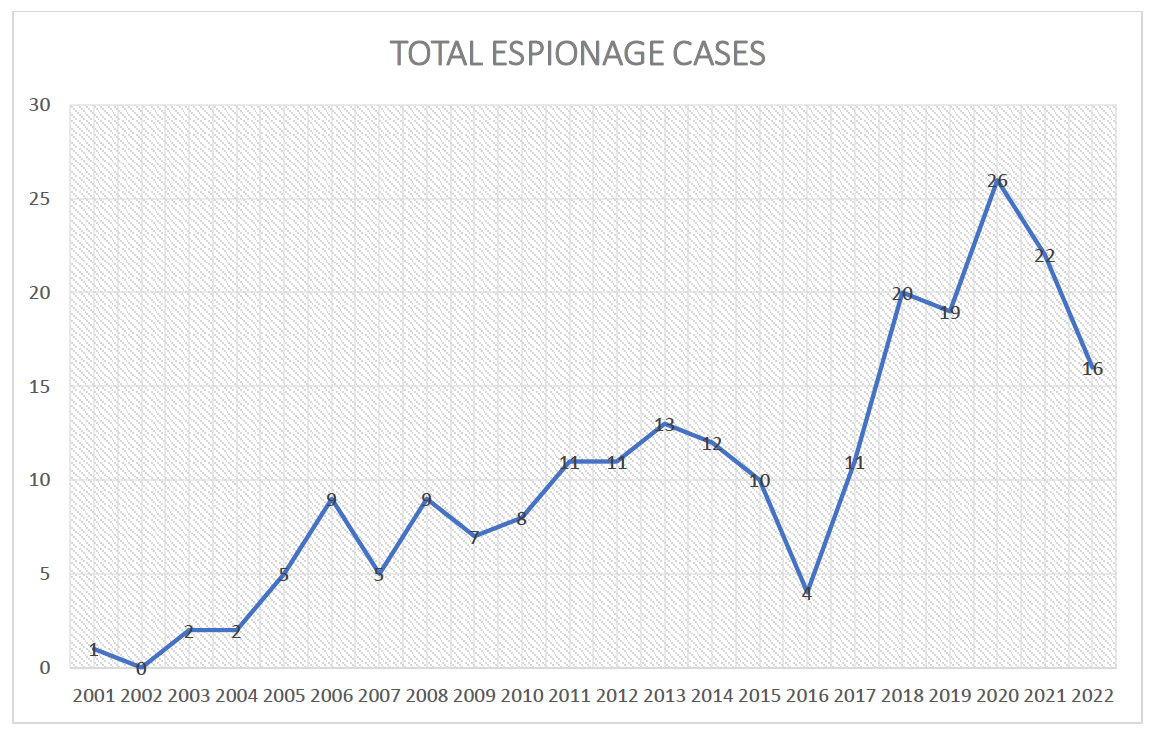

Espionage

Given the reality of mixed loyalties, it shouldn’t be surprising that skilled immigrants often constitute an espionage risk. This can be very serious. Take the infamous Pakistani nuclear physicist AQ Khan. In 1961, he moved to West Berlin as a foreign student, then to the Netherlands and finally Belgium to finish his education, graduating with a Doctorate in Engineering in 1972. Khan was undoubtedly among the best and brightest of Pakistan, the sort of high-agency STEM genius that brain drain advocates hold up as America’s greatest strength. Was allowing A.Q. Khan into the West a good decision? No.

Khan got a position at the Physics Dynamics Research Laboratory, a Dutch firm specializing in uranium enrichment via centrifuge. He stole centrifuge designs and blueprints, and after returning to Pakistan set up an international network of illicit suppliers for centrifuge parts using his contacts, leading to the 1998 Pakistani nuclear bomb. From there, he diffused nuclear technology further. The North Korean, Iranian and Libyan nuclear programs all trace back to A.Q. Khan. Pakistan has had multiple serious nuclear war scares with India in the last five years. North Korea, which has a history of doing things like axe-murder Americans, can act with relative impunity thanks to its nuclear arsenal, and Israel and the US recently bombed Iran over their nuclear program.

There are many examples from the US. For instance, Noshir Gowadia, an Indian Parsi designer of the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber, and Chi Mak, who worked on nuclear submarines, both sold secrets to China.

During the Christmas 2024 H1-B argument on X, one statistic cited by H1-B proponents was that 43% of US STEM PhDs are foreign born. This should be a five-alarm-fire. A serious country with the national interest at heart would be doing whatever it took to improve the native-born and ethnic American STEM pool rather than pretend that ethnic Americans don’t exist.

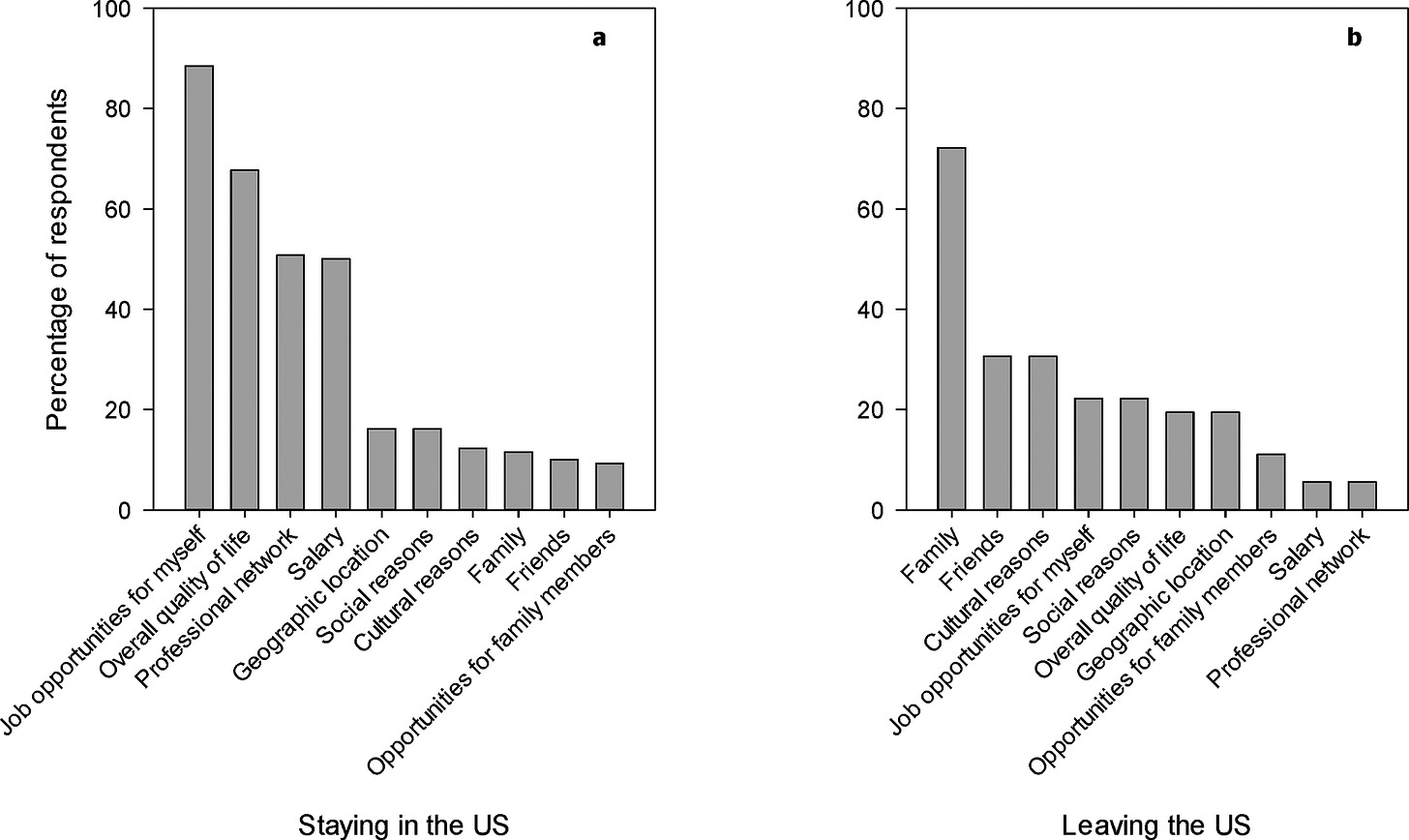

Return migration

Morris Chang, founder of TSMC, is sometimes used as an example of the folly of immigration restriction. If not for restrictionism, the narrative goes, TSMC would have been founded in America, the US would dominate semiconductor production, a high-margin and strategic industry, and Taiwan would be much less of a potential flashpoint for a devastating US-China war.14 The trouble is: Chang wasn’t deported, nor did he have his work visa denied, nor was he forced out of the US in any other way. He voluntarily chose to leave because he thought, correctly, that he could manufacture semiconductors better in Taiwan than in the United States, taking the semiconductor knowledge he gained in the US with him.15 Instead of showing why immigration restriction is self-destructive, Chang illustrates how immigration erodes technological leads, in this case US semiconductors.

The lesson is not unique to Chang. More and more Chinese academics and experts, from Apple chip engineers to Harvard math professors, have been returning to China in recent years. This is normal and there is no way to prevent this. Brain drain boosters confused the fact that many capable Chinese moved to the US because US wages and living standards were high with them having some sort of spiritual or emotional attachment to America.

Now that parts of China are developed with a high quality of life, many Chinese experts are returning, bringing knowledge gained in the US with them.16 The same thing is happening among Poles in Germany. This is why parasitically skimming the human capital off temporarily poor countries (and countries with human capital worth skimming off are only temporarily poor) rather than developing your own is a guaranteed-losing strategy in the long run. It destroys the domestic talent pipeline, and once the source country develops there’s nothing left to fall back on.

Foreign students

As part of a broader nationalist drive to catch up with the West, Meiji Japan subsidized Japanese students to study abroad. Once they’d completed their studies, these students replaced foreign experts temporarily brought into Japan.

Sending out foreign students is something farsighted states behind the technological frontier do to catch up. Because many of these students inevitably return home (and even those that don’t retain some cultural links) foreign students facilitate tech diffusion and reduce technological gaps between countries. They do not increase them. This is true in both India and China, the two biggest sources of foreign students by far (making up 54% of the total). To quote Xiaohui Liu and colleagues on the Chinese high-tech industry, “human mobility is an important source of external knowledge spillovers, and returnee presence facilitates both direct technology transfer and indirect technology spillovers to other local firms.”

This is why the extremely common belief that foreign students in the US are a source of American scientific and technological pre-eminence is not only wrong but backwards. Their preponderance in the US STEM education pipeline drives potential American scientists and engineers into finance or business, while (inevitable) return migration and links to their homeland reduce US leads.

Brain drain enables broken institutions

US-style brain drain not only reduces US leads in science and technology, it also serves as a bandaid to keep broken institutions limping along. This is most obvious with occupational licensing. Take medicine. The US has a long, expensive and restrictive pathway for educating doctors. Prospective US doctors are forced to spend four years of their lives and tens of thousands of dollars to attain an irrelevant undergraduate degree. On top of that, Medicare-funded residency slots are capped by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.

Since the supply of US-trained doctors is essentially rationed, the market mechanism cannot work properly (increased wages do not lead to more doctors). This leads to shortages, which are partly covered up by recognizing foreign licenses as equivalent to US ones.17

This artificially-produced dependency on foreign credentialing pipelines is then perversely used to argue for more immigration, via pathways such as the J-1 visa. You see the same pattern in nursing (EB-3 visa), teaching (J-1 visa, where in addition to supply being restricted, demand is mandated by law), physical therapy, and pharmacology. From the standpoint of public choice theory, this makes sense. Lawmakers respond to the concentrated interest of professional associations to reduce supply at the diffuse expense of the public. Once the problems this causes become obvious, they bow to the concentrated interest of immigrant lobbies instead of removing the legal straitjacket they created.

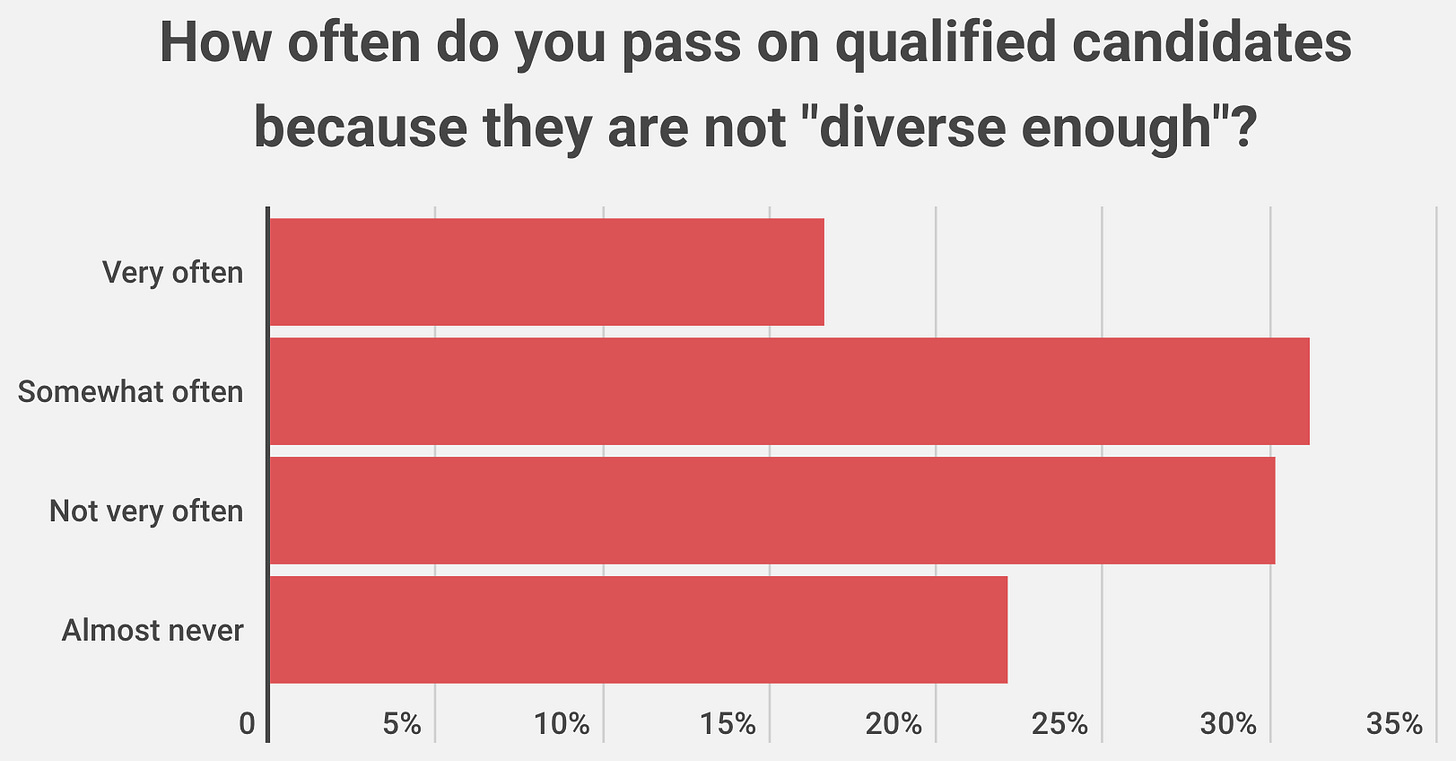

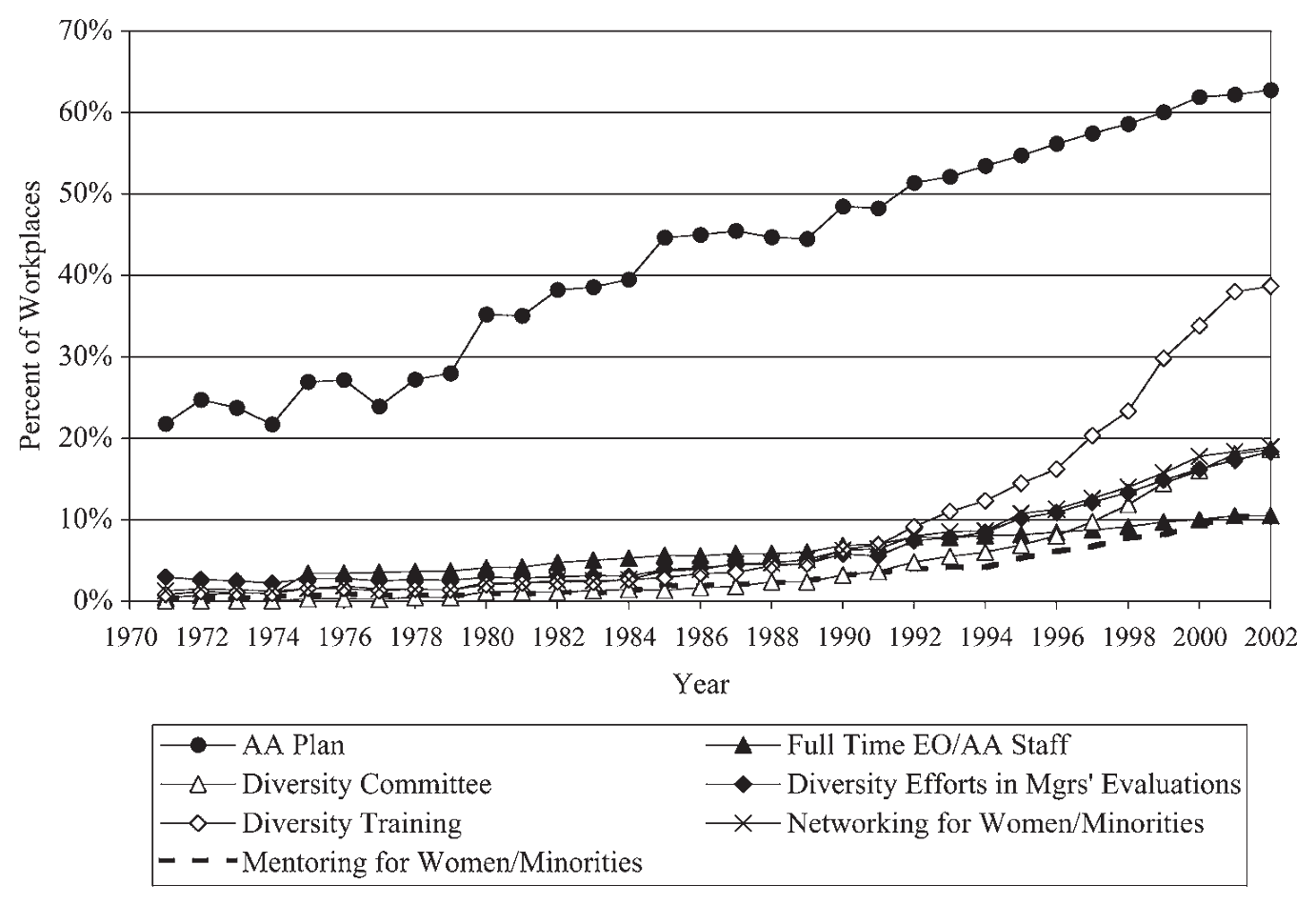

Even more than occupational licensing, the single most dysfunctional institution enabled by brain drain is affirmative action, a euphemism for quasi-aristocratic legal privileges for nonwhites and women, justified by claims of historic oppression rather than divine right. The racial privilege that gets the most negative attention is preferences in prestigious college admissions, because it is quantifiable and because Asians in particular are harmed, with Ed Blum, the strategist behind SFFA v. Harvard, having stated that he “needed Asian plaintiffs” to win.

Prestigious college admissions are only the tip of the iceberg. In particular, there’s been a generations-long political push to drive white men out of high status and well-compensated positions.18 This occurs though mechanisms such as setting aside a certain fraction of government contracts for non-white-men, and companies like Lockheed Martin, Microsoft, Nike, and Apple giving executives and hiring managers bonuses for hiring fewer white men.

The trouble is, many of these positions require specific technical skills, and for reasons of both interest and ability, the domestic technical talent pool outside of white men is very thin.

If forced to fall back on domestic sources of talent, organizations from tech companies to local governments would very quickly either compromise on “diversity” or face immediate and visible failure in the real world. But by recruiting Asian talent overseas, these institutions can keep functioning despite massive anti-white-male discrimination, with the result that the American human capital base erodes while more and more US institutions become dependent on dubiously-loyal foreigners (a recent high profile example is the Department of Defense relying on Chinese coders via Microsoft).

Conclusions

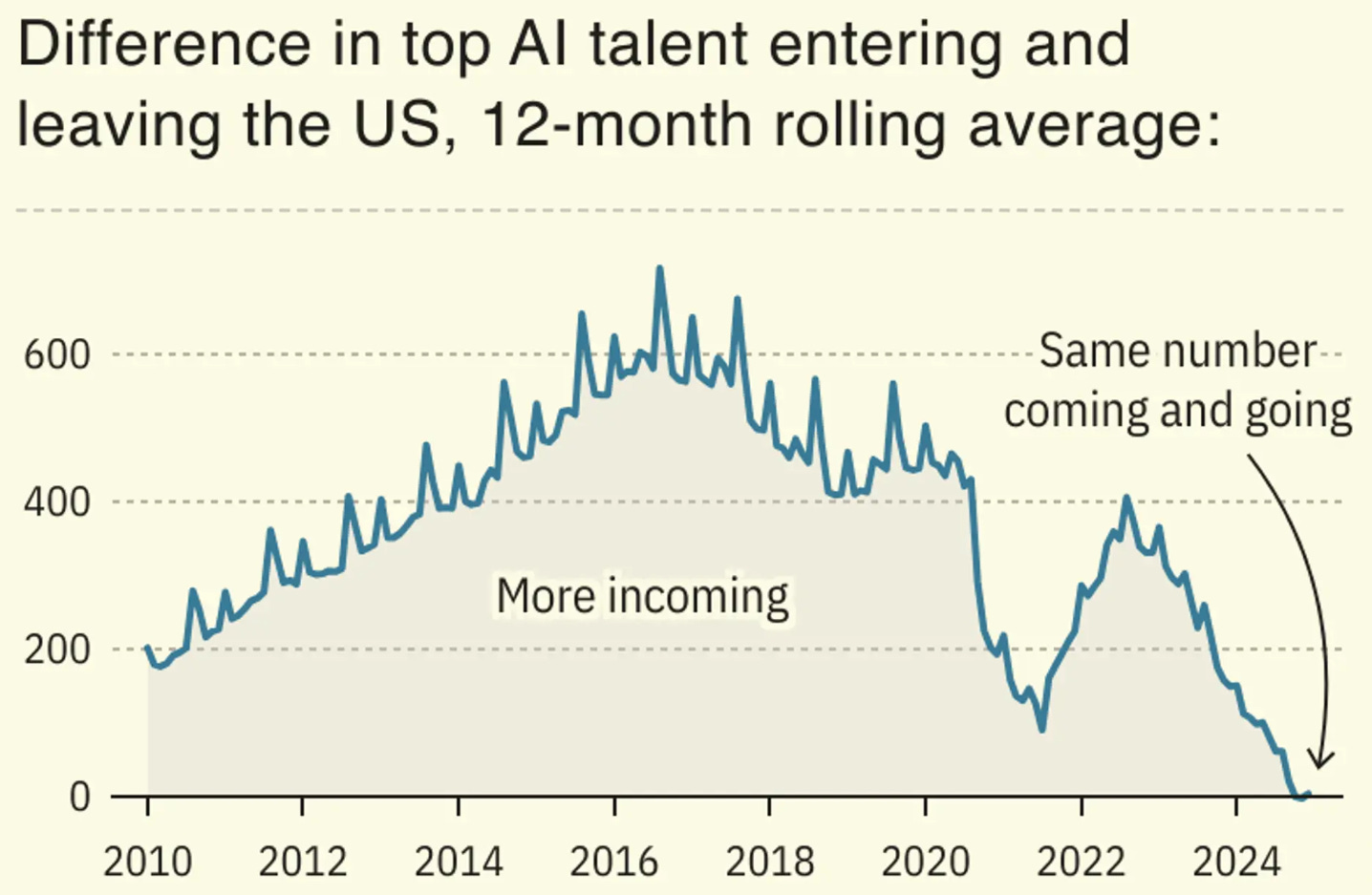

Modern brain drain to the US is not a strategic asset for the country; it is a liability. However, it could be turned into an asset by transitioning from the current “millions of mediocrities” model to a true foreign experts model of the kind that worked so well historically. For example, much writing on AI correctly points out how reliant the US industry is on foreign talent, with around 70% of high-end researchers being foreign born, and then condemns the Trump administration for hostility to immigration. But they typically fail to point out the tiny numbers involved.

We’re talking maybe 10,000 people total in the entire world, with annual fluxes into and out of the US, including during the open-borders Biden years, in the hundreds. It is entirely possible to recruit as much of this talent as is willing to move to the US while cutting skilled immigration by 99%, and we should. OpenAI technical staff and people Mark Zuckerberg is willing to pay a hundred million dollars to recruit are not generic H-1Bs or foreign students, and conflating the two is dishonest.

Successful brain drain does not require abstract “openness to immigration” at all. The most successful historical examples, Meiji Japan and Dengist China, are among the societies most hostile to immigration in all of history. And the influxes to the US in the 1930s and 1940s were accompanied by the lowest immigration levels in US history. In fact, “openness to immigration” can make absorbing foreign talent harder. Given the effects of modern immigration on internal migration, it’s clear that most mass immigration into Western countries today reduces local quality of life.

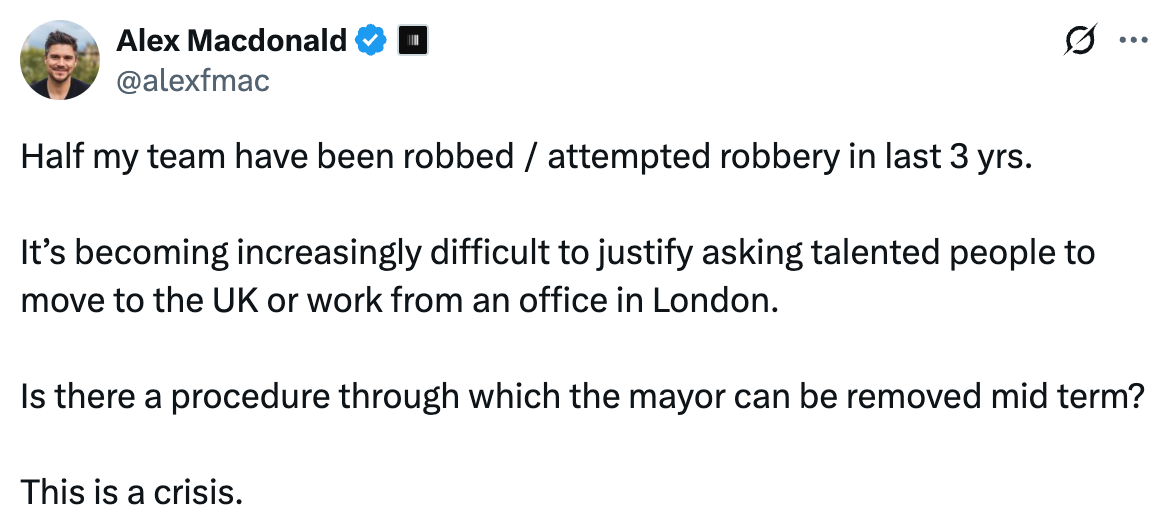

Consider how socially-housed foreign phone thieves and subway murderers make it harder, not easier, to attract the handful of European or Chinese AI experts who might otherwise want to live in London.

Instead of arguing that the US needs to be more open to immigration or high-skill immigration generally, advocates of using immigration for US geostrategy should be specific. Say which technologies the US should dominate and give names of particular foreign experts, how much they should be paid, and the total numbers of individuals involved (hundreds or thousands, not millions). Doubling down on the present system, which diffuses US technological advantages, increases vulnerability to espionage, enables broken institutions, and undermines the domestic talent pipeline, not to mention giving away the entire country, is not acceptable.

Arctotherium is an anonymous writer interested in demographics and the future of civilization. You can find more of his writings at his blog Not With A Bang or at his Twitter.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

Not to mention a lack of respect for Americans, who are apparently useless layabouts to be discarded and replaced with superior immigrants.

The path to Indian superpower is not internal development, but a friendly Indian diaspora taking control of most of the Anglosphere, including the US. Think the Israel Lobby but in support of a state two orders of magnitude larger. The path for the EU is simpler: with the world’s second largest resource of human capital, it is maybe three policy changes away from rival superpower status at any time.

Though compensation was occasionally political refuge, as with interwar central European scientist emigres to the US. Or else cooperation was simply coerced with kidnapping or prison camps, as with the Soviet exploitation of German technical expertise after WWII.

The medieval/early modern Eastern European approach of transplanting entire ethnic groups, especially Germans and Jews, as immigrants led directly to WWII and the Holocaust. It’s not like Slavs can’t learn to read or mine or trade. The US approach to “brain drain” today is much closer to the Eastern European model than the English one.

In China, this subsidy alone is worth $1.1–1.7 million dollars at PPP, but Chinese exchange rates are murky at best, so I leave the figure in renminbi in the main text.

The 1885 Alien Contract labor law, which sensibly banned labor recruitment overseas as incompatible with republicanism (since it left the composition of “the people” up to private interests), included a foreign-experts carveout, specifically for “skilled workers needed to help establish a new trade or industry” (emphasis mine). The purpose was to find experts in areas where the US was not the world leader and hence diffuse foreign technology to the US rather than the other way around. This is very different from mass recruitment of credentialed labor overseas in areas where the US dominates.

While these emigres were not at all sympathetic to the US’s major opponent at the time, Nazi Germany, the USSR was another story. Klaus Fuchs and his co-conspirators gifted Stalin the Bomb and ended the American nuclear monopoly shortly after it was created, showing the risks of relying on foreign talent. This is why, rather than continuing to rely on the European scientific ecosystem during the Cold War, the US used the European physicists so important in WWII to set up an American domestic nuclear talent pipeline (the whole US security clearance infrastructure, one of the very few areas where modern USG still discriminates against the foreign-born, grew out of this).

And because Americans are the “state-forming people” of the US willing to sacrifice for the country, it wouldn’t even work in a crisis where US geopolitical power became necessary, as opposed to merely “nice to have.” How many H-1Bs would show up if we had a draft and were fighting WWIII?

American policymakers and intellectuals were criminally stupid, treacherous or naive about China from 1991—2016 or so. By 2008, the CCP was explicitly talking about the US as the main enemy, ideological subversion as the major threat, and replacing the US as world hegemon as the major goal. It took another 8 years for Trump to actually force recognition of this on the US political sphere, by which time internal US trends and Chinese technological development combined to make doing anything substantial about it difficult at best. Charlie Munger and Pat Buchanan both got this right in their own ways.

I find the combination of ethnic triumphalism incompatible with national feeling (“Indians are taking over”) with dripping racial resentment (“despite the racism, xenophobia, and other ‘usual minority problems”) common in Indian diaspora discourse in the US [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] wholly objectionable and seeing it again and again is what initially inspired me to start looking into the views of the Indian diaspora. This sort of anti-white racial hostility is common to many minority groups in the US, but is particularly noxious in the case of Indian Americans, effectively all of whom immigrated after 1970 and hence have always received racial privilege. The vast majority are 21st century immigrants parachuted into upper-middle-class American life immediately upon arrival. They therefore have zero legitimate grounds for grievance; it’s nothing but ethnic enmity. I am, of course, generalizing here, and not all Indians behave this way. But far too many do, and immigration policy, implemented by indifferent bureaucracies that cannot possibly evaluate individuals for loyalty, needs to look at rules and not exceptions.

He’s not totally right, of course. All the ethnic networking in the world wouldn’t create this success if Indian-Americans weren’t talented. They are, thanks to very selective migration.

There’s something of a celebration parallax here. If you say Indian ethnic networking is part of the explanation for Indian success in the US, and that’s a good thing, no one bats an eye. If you say Indian solidarity exists and is both a bad thing and evidence that most Indians in the US are not Americans, you’re in trouble.

See Anita Raghavan’s The Billionaire’s Apprentice, which, as is typical in Indian diaspora discourse, portrays this in a positive light.

Given the dominance of East Asia in manufacturing (a product of a homogenous and high-IQ population, very low wages relative to the US, especially in the 20th century, crushing organized labor, and looser environmental standards), I think this is probably wrong. If TSMC had not been founded in Taiwan, chances are the leading chip manufacturer would be in South Korea or Japan.

This is sometimes portrayed as going home, but that’s not strictly true, since Chang was from mainland China—though Taiwan is still legally considered part of China and this was much more true during the Cold War.

The data on Chinese who study abroad are sobering. As recently as 2000, about 40,000 Chinese students were studying abroad, and only a handful returned to China afterward.22 By 2018, however, China’s Ministry of Education reported that there were 662,100 Chinese studying abroad, 480,900 of whom (73 percent) returned to China afterward. A recent news story reported that about 1.6 million Chinese students now are studying abroad and that about 400,000 of these individuals are at academic institutions in the United States.

Ireland and Britain have very similar problems, with half of foreign doctors in the NHS being below British standards, widespread qualifications fraud, and enormous overrepresentation of foreign-trained doctors in medical misconduct cases.

Some people are under the mistaken impression that affirmative action (“DEI”) is a recent phenomenon, especially outside of education. It is not. Chapters 4 and 5 of Jared Taylor’s Paved With Good Intentions, written in 1992, goes into the many forms this system has taken for generations, starting with Lyndon Johnson’s 1965 Executive Order 11246 demanding contractors take “affirmative action” to ensure nondiscrimination against protected categories. Since there are no hard criteria to establish discrimination, this has led to an arms race of different entities competing to give more and more privileges to people who aren’t white men.

This is a thoughtful article that covers this topic well. You didn't mention the Dubai model. Something like 80% of the country is foreign. Indians make up a huge chunk of that foreign population. But the UAE does not give them a path to citizenship. It is extremely rare for a person to be granted UAE citizenship.

We could implement something similar. Make it much harder for someone to become a US citizen. Instead the current 5 year residency period, we can make it 10 years like Switzerland. And not only that. We can also require large payment a requirement for the citizenship application. Trump is selling "Gold cards" for $5M a piece. A lot of countries have citizenship by investment. By making $1M a requirement for ALL naturalization, we will have solved the problem of the Somalians, Haitians, and Guatemalans changing the politics of the country.

And this $1M entry would still allow people like the $10M AI engineer to become a US citizen.

The H1-B visa program is the modern equivalent of importing Chinese “coolie” labor into the US to build the railroads in the 1800s.