Written by Arctotherium.

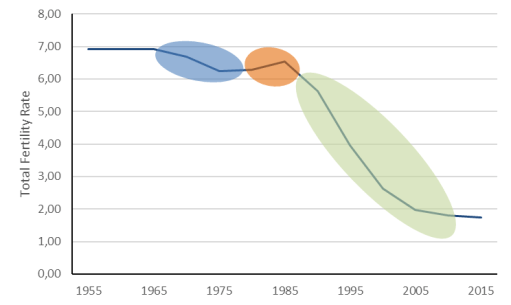

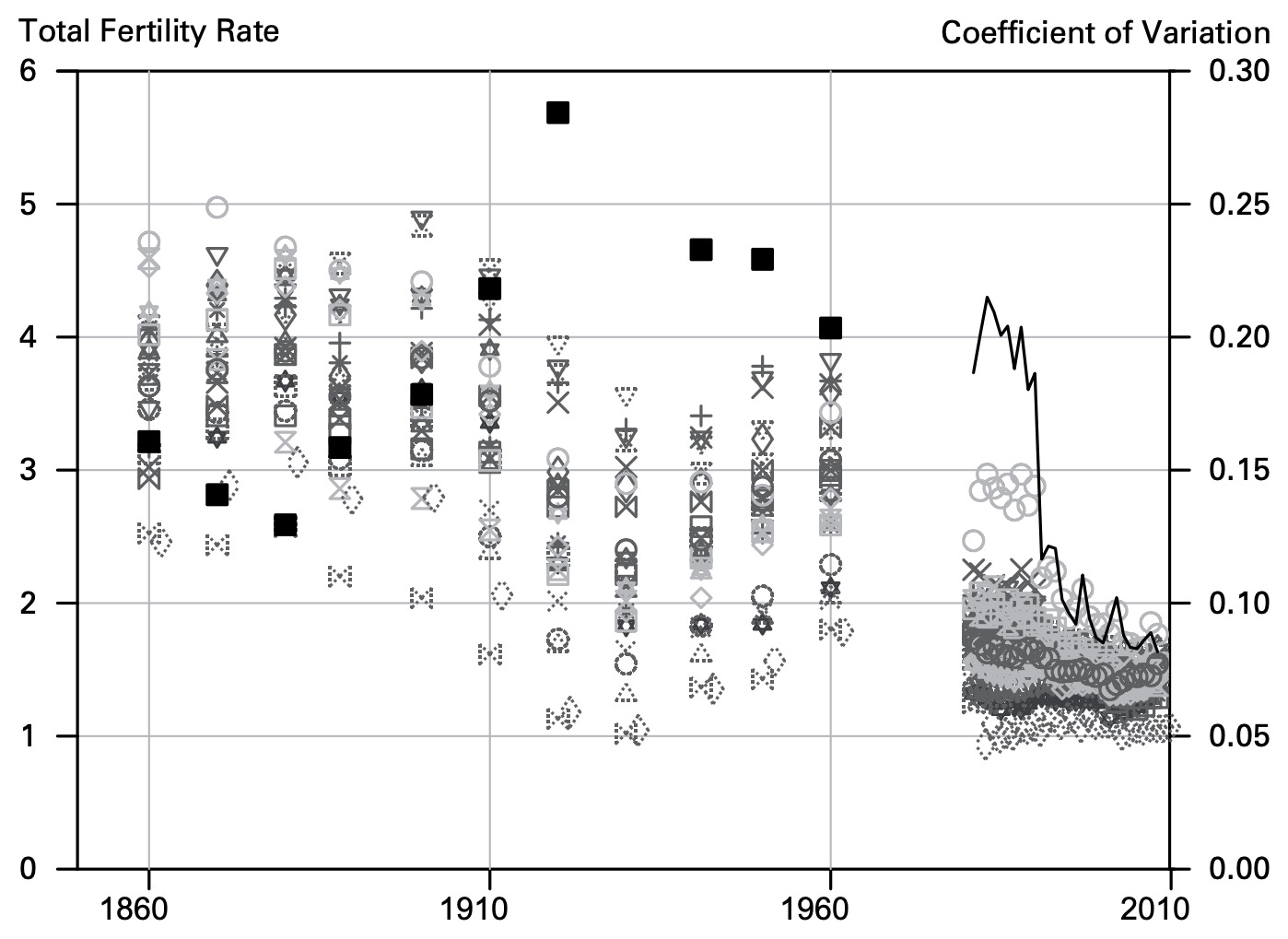

No one seriously disputes that state policy can lower fertility. Consider the case of Iran. Like many Asian countries (India, China, Singapore, South Korea) concerned about overpopulation, Iran started a population control policy in the 1960s. The Iranian Revolution initially reversed this on the grounds that it was incompatible with Islam. But even the ayatollahs could do the math and see that Iran’s agricultural land was nowhere near sufficient for a population in the hundreds of millions (especially when cut off from Western agricultural technology and expertise). So they sharply backtracked in the 1980s, leading to the fastest fertility collapse in history.1

But it’s undeniable that state pro-natalism in the 21st century doesn’t work well.2 Hungary spends about 5% of GDP on fertility programs, including large financial benefits (70% of median wage) to new mothers, large tax credits for mothers (including full income tax exemption for mothers with four or more kids), and subsidized loans (scaling with the number of kids) and savings. Plus, there’s free IVF.

France has already implemented most of the modern pro-natalist wish list (reducing income tax rates based on the size of the household, cash payments to mothers at birth, cash allowances for families, subsidized child care, universal paid parental leave, school cost payments, and housing subsidies for families with three or more children), though many of these programs are means-tested, and the French state has been ideologically pro-natalist since the interwar period. In total, France spends about 3.6% of GDP on family programs, rising to 4.7% if you account for the indirect income tax adjustments and pensions benefits (the highest in the OECD).

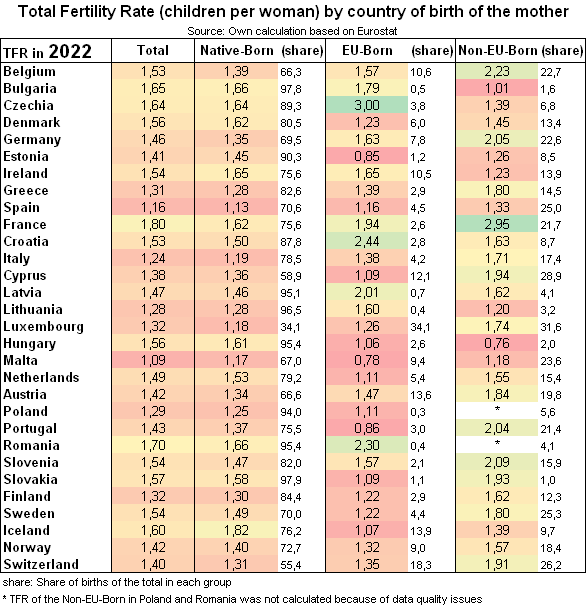

France does have the highest fertility in Europe… but this is largely due to the exceptionally high fertility (TFR = 2.95) of non-European immigrants, who account for 22% of total births. Rather than bringing French fertility to replacement, the French pro-natalist state overwhelmingly subsidizes large families in the massive Arab and African populations (which makes the problems of population decline worse, not better). Contrary to the Age of Malthusian Industrialism hypothesis, native French fertility (TFR = 1.62) is at the high end for Europe but by no means exceptional. And even this is probably increased by earlier generations of Arabs and Africans, since France has a much longer history of significant non-European immigration than other European countries (though it’s impossible to say by how much because France does not keep racial or ethnic statistics).

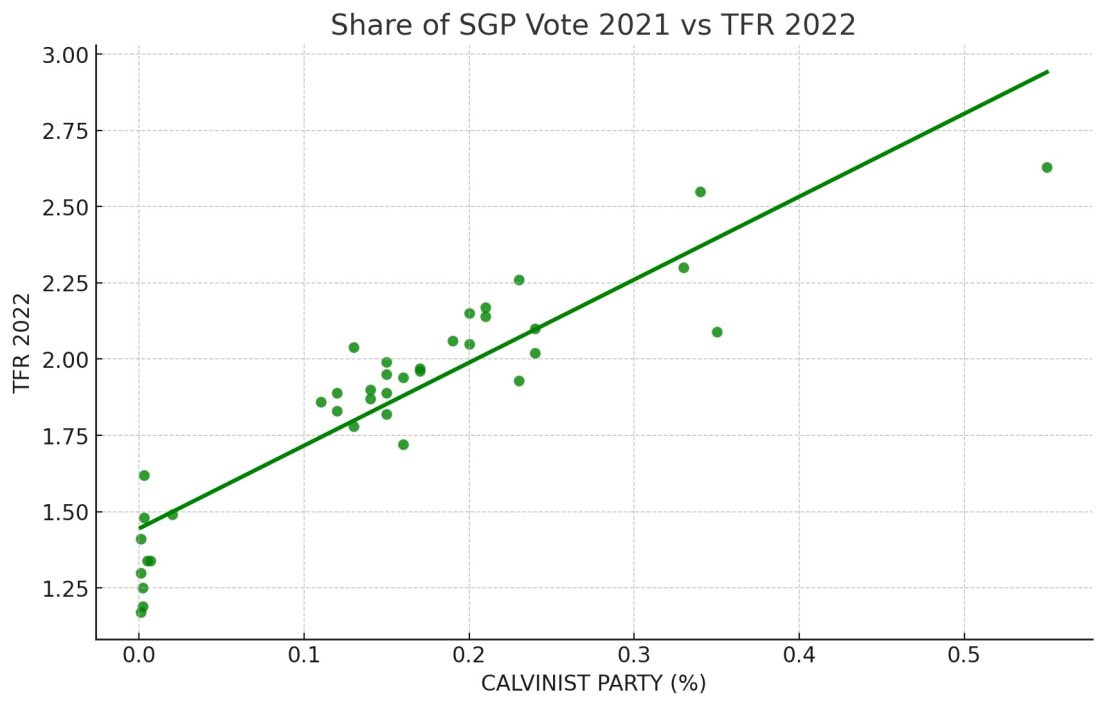

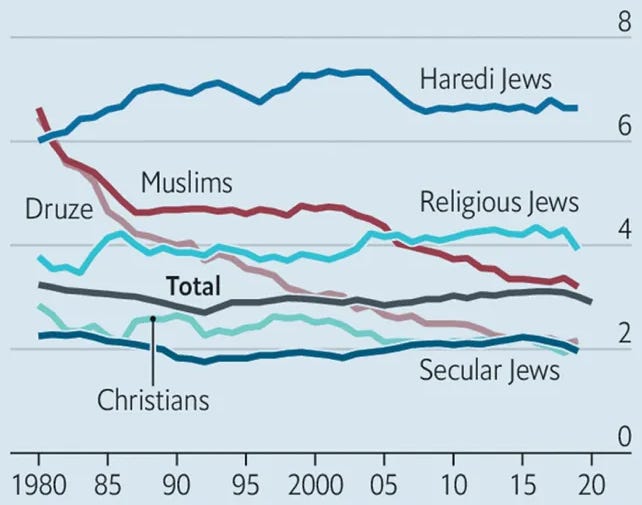

The only really effective high-fertility groups in economically advanced countries are patriarchal and pro-natalist religious groups, which are often separated from mainstream society by technological choices or language barriers. Some examples are the Haredim3, practicing non-ultra Orthodox Jews4, the Amish, orthodox Dutch Calvinists (strict enough to oppose women’s suffrage), and Finnish Laestadians. As a rule, the more culturally separated from mainstream society, the higher the fertility and the lower the attrition out of the group.

However, there are some interesting historical exceptions to this rule in the Cold War Eastern Bloc. Communist governments saw their people as tools of the state5, not individuals and citizens valuable in-and-of themselves. A larger population meant more workers, farmers, engineers and soldiers, the better to build socialism and defeat Western capitalist imperialism. This was particularly critical in command economies where growth came from increasing inputs rather than efficiency. Since large-scale immigration was not an option, several Eastern Bloc states tried to increase their subjects’ fertility.

This impulse ran headlong into the fact that Communism was ideologically feminist and atheistic. Communist states promoted female entry into higher education and the formal workforce (during the first half of the Cold War, the fact that Western states didn’t do this was one of the superior features of the West pointed out by Soviet dissidents such as Solzhenitsyn). They also removed taboos on promiscuity, premarital sex and illegitimacy, and destroyed the high-fertility religious groups so noticeable in the West. These social changes were not as complete as their post-60s Western counterparts because so much of Eastern Europe’s population comprised rural and backward peasants partly cut off from the culture of the center, and because they were top-down, not in any way organic.6 Yet they still greatly changed Eastern European life. While hormonal contraception was rare, abortion was incredibly common in the Eastern Bloc, essentially serving as a one-for-one substitute.

While nowhere near as successful as the Western Baby Boom, Eastern Bloc pro-natalism is worth studying — for two main reasons. The first is that the Eastern Bloc’s legal and political regime governing sex relations was much closer to Western countries’ today than to that of the Baby Boom-era West.7 The second is that, unlike the Baby Boom, which was not planned and arose from the spontaneous interaction of the Western European Marriage Pattern and postwar prosperity, the Eastern Bloc pronatalist programs were state policy. It’s much easier to copy laws than to socially engineer society from scratch.

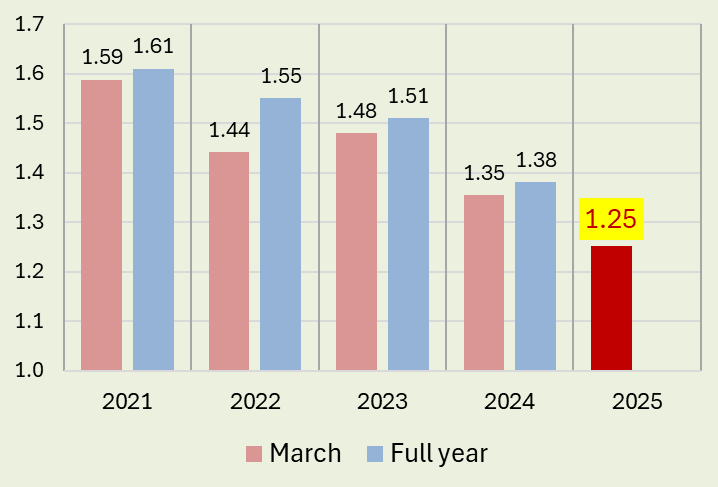

There’s another reason Eastern Bloc pro-natalism is worth studying. After decades of strong anti-natalism, the CCP has reversed course and is now promoting marriage and larger families. It doesn’t matter much over the next couple of decades8, but whether China has a TFR of 0.9 or 1.8 might be the most important fact in the second half of the 21st century. I don’t know if they will be successful: it’s very difficult to rebuild a large-family culture after an entire generation without them, and East Asia’s propensity for extreme negative-sum status competition is a major obstacle.

The Soviet Union

As the biggest, longest-lasting and most important Eastern Bloc country — and the only one in which Communism was not imposed by a foreign army — the Soviet Union has the most complex history with family policy and pro-natalism.

In line with orthodox Communist views on the family, the early Soviet Union imposed both a Sexual Revolution and second-wave feminism from above. Specific initiatives included:

Paid maternal leave two months before and after childbirth (1917).

Women were given both the right and obligation to work in the 1918 constitution, with sex quotas introduced in 1920. Common marital property was abolished, which meant that a woman had no right to property officially owned by her husband. To attain rights to possessions, women had to work for a wage in the formal sector. More sex quotas protecting women from being fired were introduced in 1922.

Legalization of homosexuality (1917).

Women were no longer expected to take husband’s surnames (1917).

Abolition of the legal categories of legitimate and illegitimate children, with children receiving the same rights both inside and outside of wedlock (1917). Paternity was recognized and enforced through the courts based solely on the request of the mother. Her word alone was considered sufficient proof, and a mother could receive child support from multiple potential fathers.

The introduction of no-fault, unilateral divorce (1917). Women, though not men, were entitled to alimony after a divorce.

Legalised abortion, which was provided free of charge (1920). By the mid-1920s, abortions in Moscow outnumbered births by 3 to 1.

Unlike their 1963-73 Western equivalents, these changes were entirely top-down, and they did not require those making the changes (the Communist Party) to give up any power. Furthermore, the early Soviet Union was not nearly as connected and integrated as the Western world in the 1960s. The reach of the Soviet state in the countryside where the vast majority of the population lived was limited until collectivization began in 1929, which is when Soviet fertility really collapsed.

Recognizing in the 1930s that the Soviet Union desperately needed military and industrial strength, and that the disintegration of the family and collapse of the Russian birth rate threatened this, Stalin partly reversed the changes to family policy. His reforms included:

Banning abortion except to protect the life of the mother (1936).

A 6% childlessness tax applying to men aged 25–50 and married women aged 25–45 (1941). To this was later added a 1% tax for those with 1 child and a 0.5% tax for those with two.

State allowances to mothers of large families (initially 7 children, later reduced to 3), and single mothers (1944). Note that single mothers in a country where 40% of prime-age men have been wiped out are different from than those in one with a balanced sex ratio. The allowances were halved in 1947.

Official state recognition and encouragement of large families with medals, title, and honors — starting at five children and increasing in prestige with each child. Mothers with 10 or more surviving children were given the title “Mother Heroine” along with privileged access to goods, public utility payments, and a state pension (1944).

Women losing the ability to appeal to the courts for alimony and recognition of paternity unless they were cohabiting in a registered marriage (1941).

Making divorce more difficult by requiring motives, a fee, a court obligation to attempt reconciliation between the spouses, and publication in the local newspaper (1944).

Soviet demographics were absolutely devastated by WWII, with about a third of adult men dying in the war and many more being left crippled. This greatly limited Russia’s postwar population boom, but it maintained a TFR of around 3 under Stalin’s pro-natal policies, which allowed a partial recovery.

As with many of Stalin’s reforms, some of these initiatives were rolled back with destalinization in the 1950s, and other pro-natal incentives were put in place. In particular, abortion and divorce were made easier, but the monetary incentives for children were increased. In this way, the post-Stalin Soviet state came to more closely resemble its modern counterparts. Some specific changes were:

The re-legalization of abortion in 1955. Abortion quickly became by far the most important instrument of family planning again.

Monthly allowances for children of men in obligatory military service.

Divorce being made easier in 1969 by involving the Registry of Civil Deeds (ZAGS) rather than the courts (though it was still more difficult than it had been before 1944).

Pregnancy and maternity benefits (already equal to 100% of salary) being extended to all women regardless of employment record in the 1970s.

During this period, Russian TFR dropped from around 3 to around 2, where it remained until the fall of the USSR. While higher than the US and most other Western countries in the second half of the Cold War, this was still disappointing. In the 1980s, the Soviet state tried a couple of other incentives, namely more money and prioritizing young couples for housing.

There was a lump-sum of 50 rubles at first birth, 100 rubles for subsequent children of working mothers, and 30 rubles for non-working mothers.

The USSR adopted a policy from East Germany in which young married couples were given priority for rooms, and young married couples with children priority for apartments, as well as interest-free loans.

These seem to have worked better: Russian fertility rose in the last decade of the USSR despite a terrible economic situation. But Soviet pro-natalist initiatives collapsed with the fall of communism, and there was a 15-year interregnum with very little deliberate family policy in Russia. The modern Russian state maintains several pro-natalist policies, but has little continuity with its Soviet equivalent and the same flaws as its Western equivalents.

East Germany

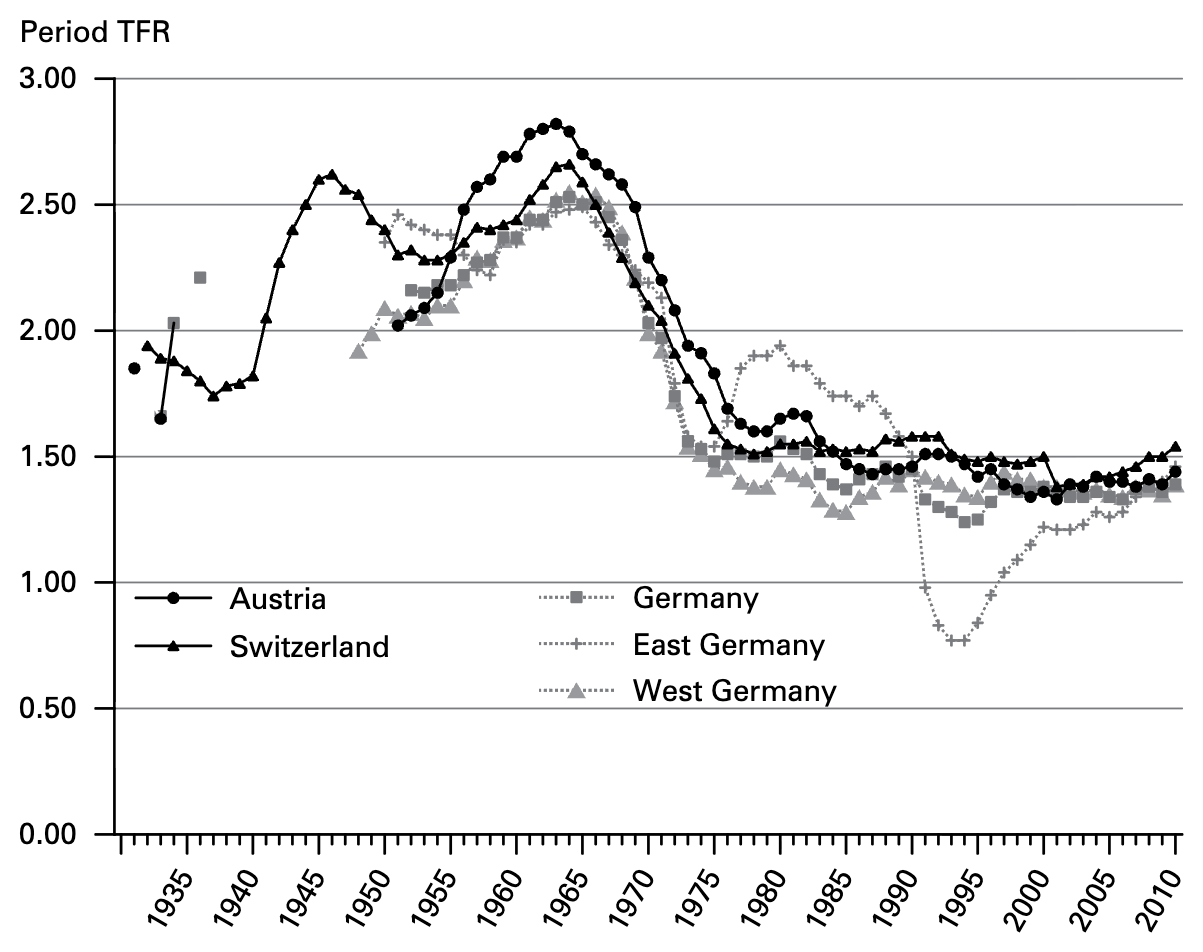

Fertility in the countries of Germanophone Central Europe followed very similar trends after WWII.9 They had an anemic Baby Boom (which is why Germany is one of the most aged countries in the world today), followed by the Second Demographic Transition collapse to one of the lowest TFRs in Europe. But East Germany is noticeably different, with significantly higher (though still below replacement) fertility between the end of the Baby Boom and 1990, and then significantly lower from 1990 to 2008.

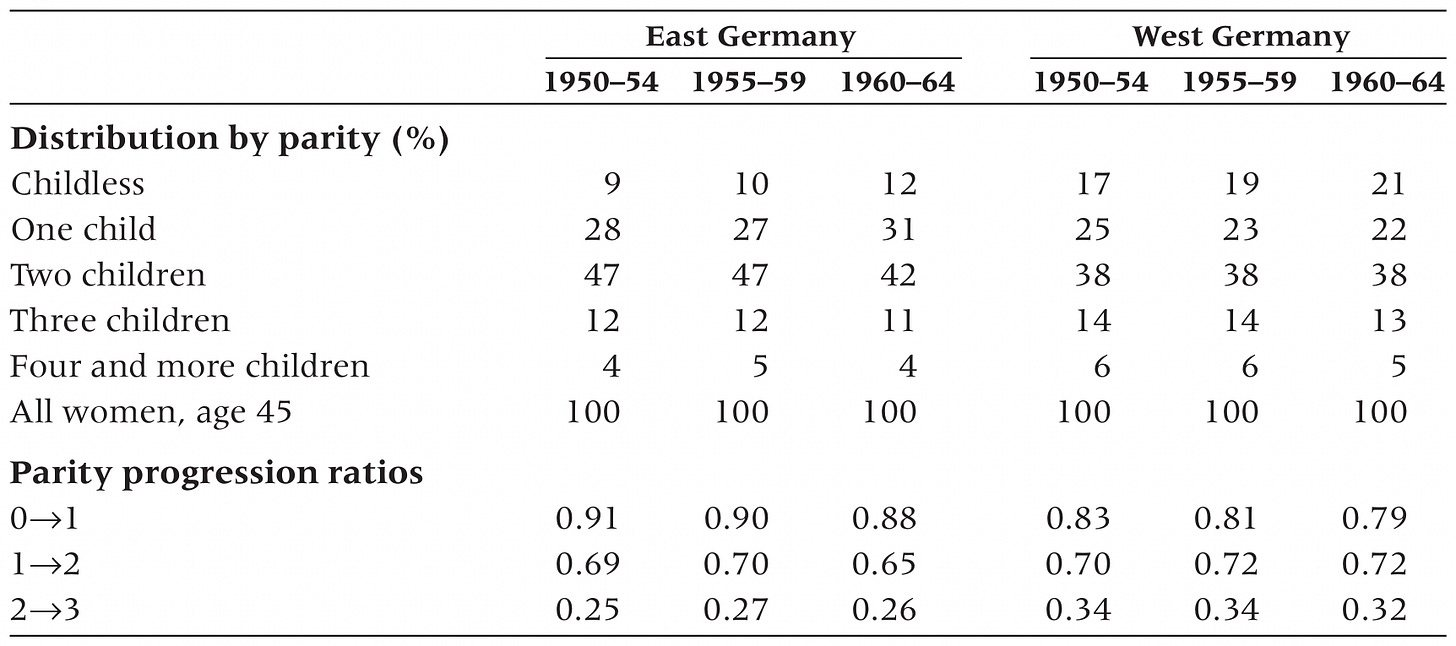

East Germany introduced several pro-natal reforms to combat fertility collapse: financial incentives for marriage and birth (1972); free daycare for children over 1 year (1972); and a “baby year” of leave for new mothers after birth with full pay and a guarantee of keeping her job (1976). This seemingly worked, but with one big caveat. The measures were designed to promote large families, but East Germany had fewer large families than the West throughout the relevant time period.

The East German TFR advantage came from two sources. First, lower childlessness, peaking at 12% when the Berlin Wall fell versus 21% in West Germany. And second, early age at first birth. Both the 1975–1990 advantage and the 1990–2008 disadvantage were partly timing effects10, with East German women having kids earlier in the late Cold War and then later in the post-reunification chaos. Average age at first birth in East Germany in 1989 was 22 (the same as in the US in 1970) versus 27 in West Germany.

The reason for both these differences is simple: East Germany had a chronic housing shortage. You might think this would reduce fertility, and it would in a market economy, but East Germany was a command economy where houses were rationed rather than sold. If you wanted to move out of your parent’s (tiny and cramped) apartment, you had to get married and have a kid. “In most cases, it was the only way to get an apartment in the state-controlled allocation system.” This strongly encouraged both early marriage and family, and was very effective, though it did not encourage large families. East Germany’s various baby bonuses and transfers to parents, which were designed to promote large families, had little impact.

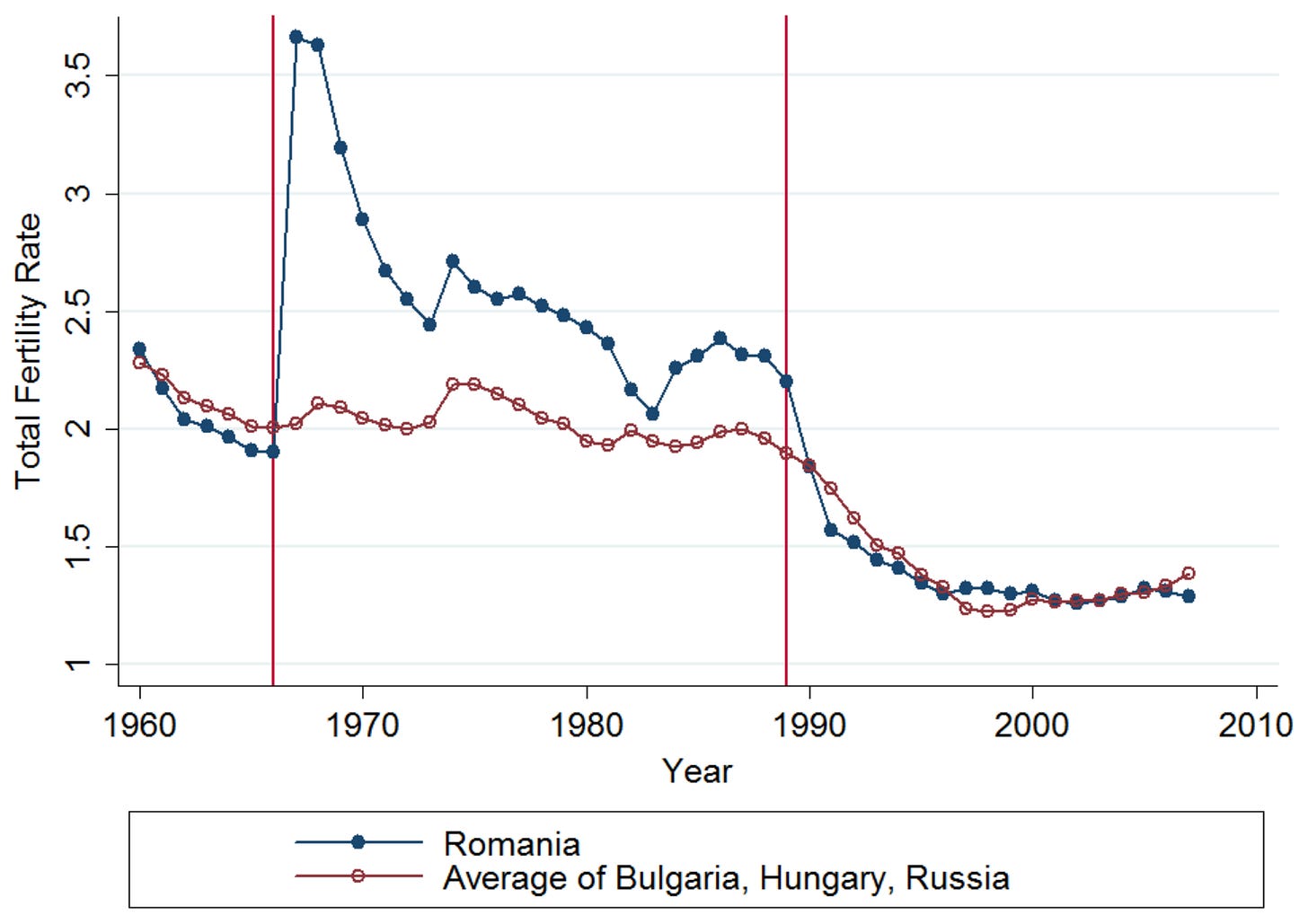

Romania: Decree 770

By far the most successful, and infamous, example of Eastern Bloc pro-natalism is that of Romania. In 1967, dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu banned abortion in almost all cases (except rape, incest, the life of the mother, women over the age of 45, and women who already had large families). Modern contraception wasn’t banned, but was nearly impossible to obtain as the state stopped importing it from the West. This was enforced by monthly gynecological visits, with discovered pregnancies monitored to term. TFR nearly doubled from 1.9 to 3.7 in a single year.

The extraordinary initial increase was transient. Romania’s social structures and sexual norms relied on widespread abortion to manage fertility, and when that was suddenly banned people didn’t immediately change their behavior. As such, there was a short, sharp spike in births, with infamous social consequences: a massive spike in children abandoned at orphanages and maternal mortality ten times higher than comparable Eastern Bloc countries. Romanians needed a few years to adapt to the new regime, but adapt they did, and Romanian fertility quickly came back down. Still, it remained persistently higher than peer countries until the collapse of the Eastern Bloc.

Ceaușescu didn’t just ban abortion and contraception. He also levied an additional income tax on childless individuals over the age of 25, as well as implementing more common pro-natalist policies such as family allowances scaled by the number of children, maternity leave, mandatory workplace nurseries, and propaganda campaigns. By 1985, public expenditure on these material incentives equalled half the defense budget — in a state dedicated to eliminating the national debt. The Romanian bachelor tax was initially 10% on incomes below 24,000 lei and 20% on incomes above 24,000 lei, much higher than its Soviet equivalent, and it may have been raised later.11

What Decree 770 shows is that it’s entirely possible for a powerful state with sufficient disregard for its subjects to raise fertility above replacement by brute force even under state atheism and second-wave feminism. Of course, Ceaușescu was the only Eastern Bloc leader executed after regime change, so this approach does have its risks.

Conclusions

I do not believe that Eastern Bloc pro-natalism is either replicable or desirable. However, the record of the various interventions that were tried paints a clear picture of which ones worked and which ones didn’t. From least to most effective, you have:

Monetary transfers.

Medals, honors, and pro-natal propaganda.

Restricting housing to married couples, ideally with children.

Restrictions on divorce (Stalin only).

Completely banning all forms of abortion and contraception.

Unsurprisingly, the interventions that have been adopted by modern pro-natal states were the least effective. The efficacy of China’s pro-natal efforts will be determined by how far down this sequence they’re willing to go. (I claim no special knowledge about the inner workings of the PRC).

Appendix: the flaw with most modern pro-natalism

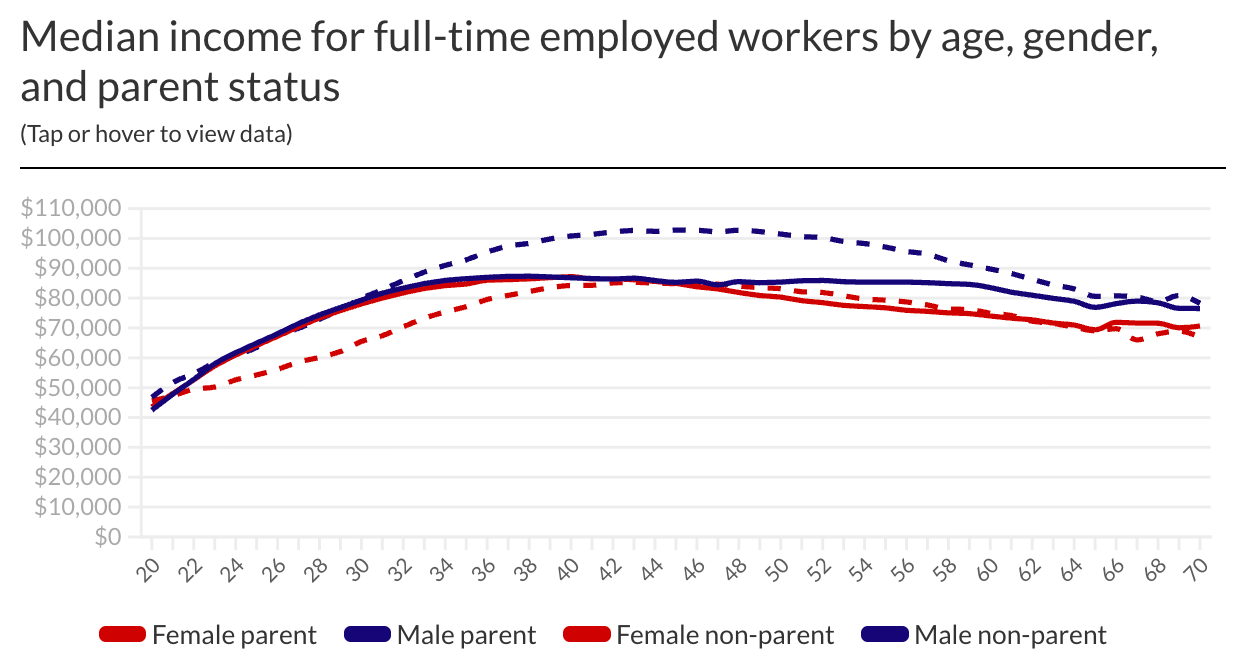

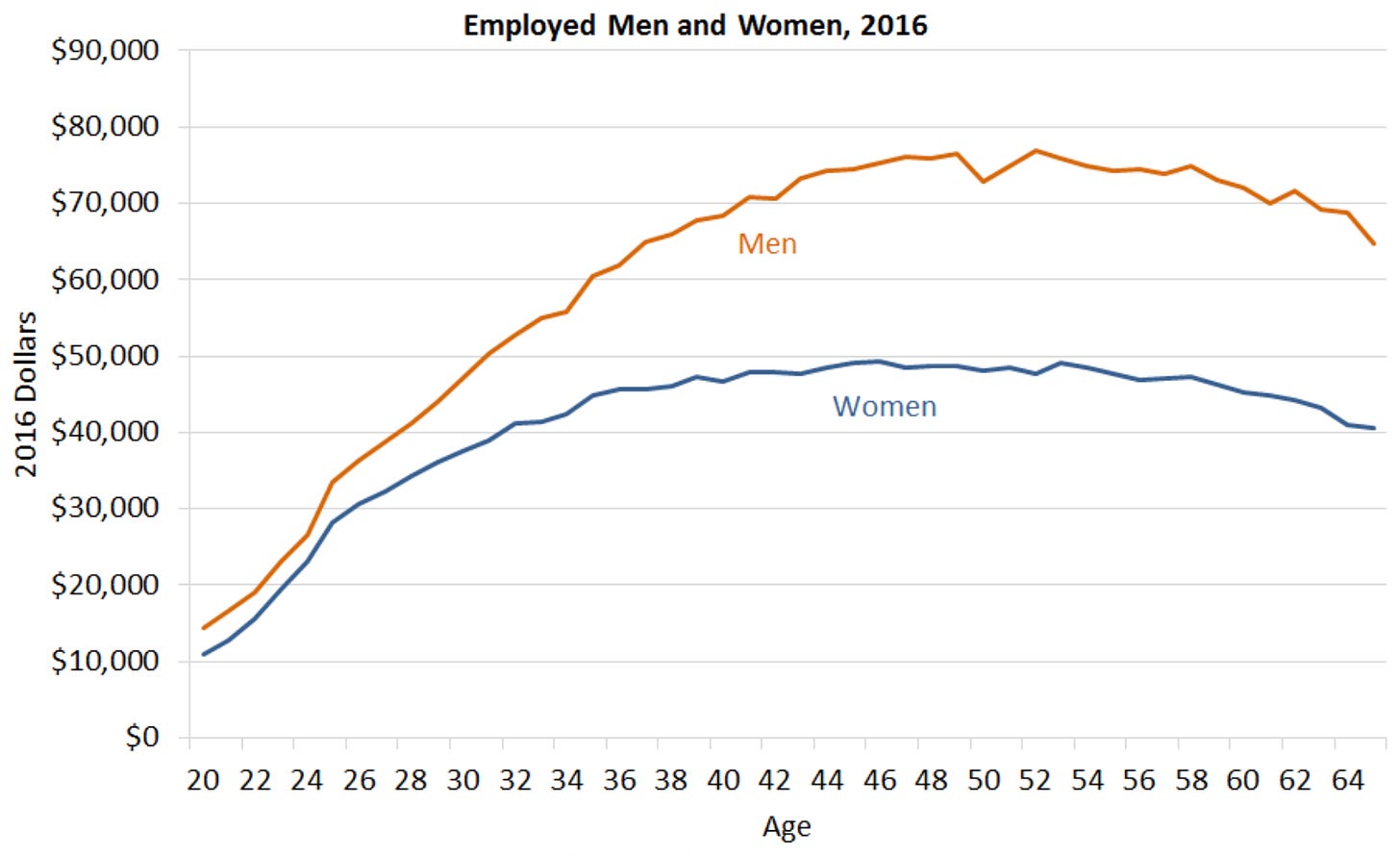

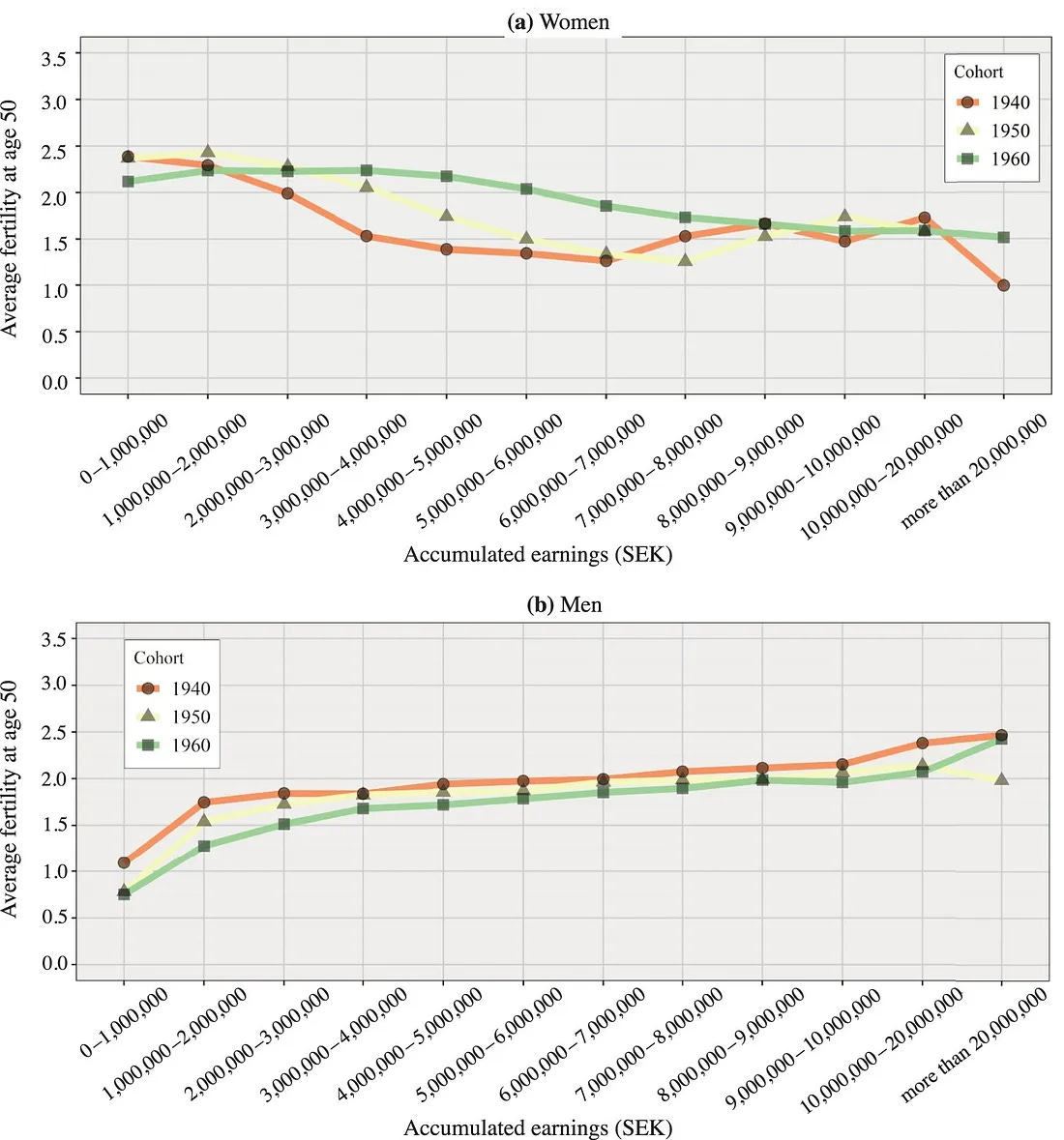

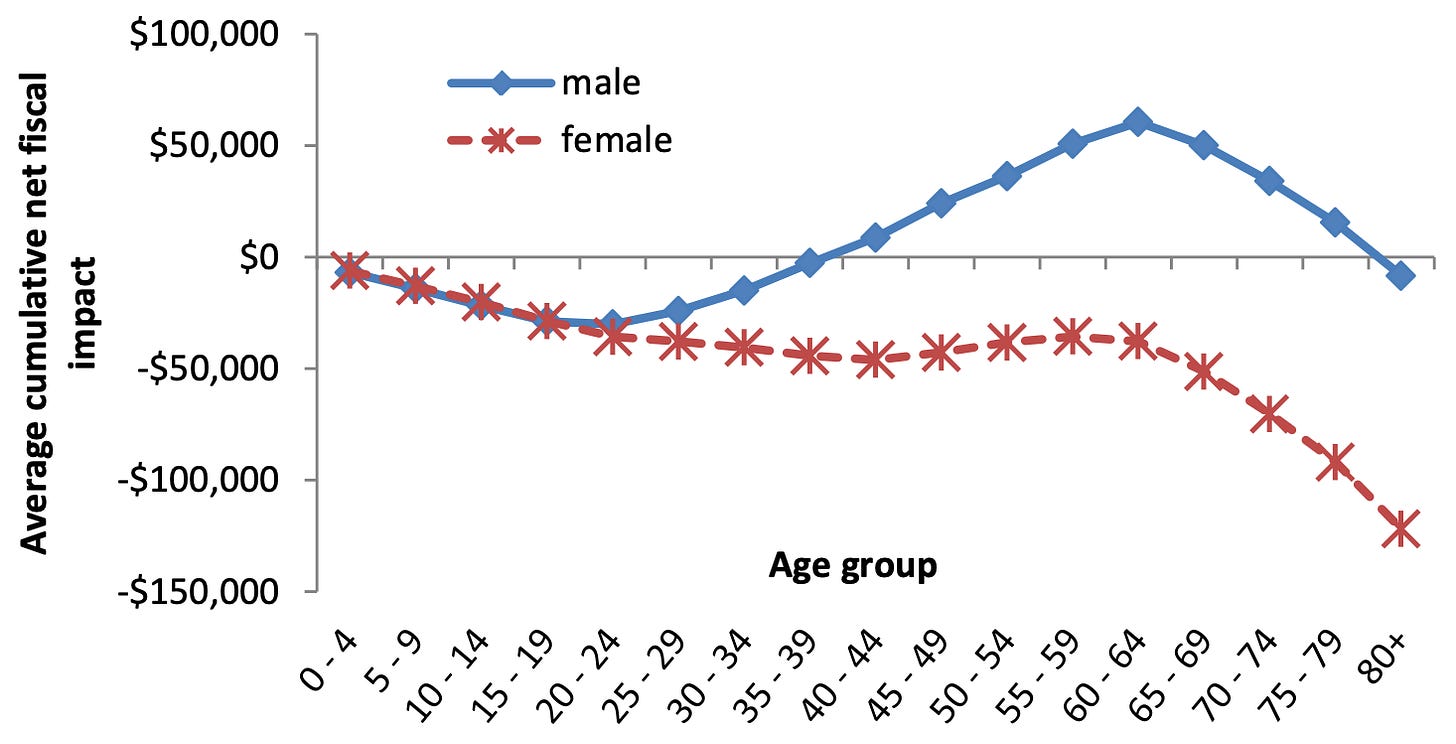

Most modern pro-natalist efforts and proposals, like JD Vance’s $5,000 Child Tax Credit, consist of some form of monetary or in-kind transfers (such as state-subsidized child care) to mothers. These transfers have to be paid for by taxes. Men pay most taxes.12

And not just men, but married (or long-term cohabiting) fathers.

But this is exactly the group for which income translates to more children! So you have a case where, to pay for pro-natal incentives, the men who need money for larger families have their income reduced and labor disincentivized through higher taxes. That doesn’t mean direct monetary transfers for children are totally ineffective, but the taxes required to pay for them very much work at cross-purposes with the intended goal. The taxes required, and whom they fall on, is one explanation for why Nordic pro-natal states have largely failed.

This is even more true for other common pro-natal interventions. Consider Hungary, where women are exempted from income tax after a certain number of children, which in turn discourages the male-breadwinner family model and places the tax burden even more squarely on the shoulders of married fathers. This policy has effectively erased the sex gap in income. Unsurprisingly, despite being very expensive, it has not worked well.

Most in-kind transfers, like free childcare, are even worse, because they increase female earned income — and the higher the lifetime earned female income, the lower the number of children.

A recent study from Spain found a near perfect inverse relationship between how much a pro-natal program increased fertility and how much it affected women’s earned income (only promotion subsidies raised both).

So you effectively have a situation where the group for which income actually translates to children have their income reduced to pay for pro-natal incentives. This renders those incentives much less effective than they should be on paper when they comprise cash, and actively counterproductive when they comprise in-kind benefits. Just about all commonly-floated pro-natal policies fall into one of these two buckets.

The obvious response is that pro-natal policies and monetary incentives should focus on increasing men’s income, especially men’s earned income, relative to women. If this isn’t politically feasible, the correct thing for governments to do is nothing beyond supporting non-mainstream religious groups through opt-outs from public education. I’d note that the US, with its limited pro-natalist policies, has higher native and white fertility than almost every country in Europe.

Appendix: more firepower?

One argument is that modern pro-natalist efforts would work, but the numbers are just too small to achieve their goals — and the solution is more money. What about a $200,000 lump-sum payment per child? The US has about 3.6 million births per year, so this comes out to $720 billion per year. That’s a lot of money, but not so much the government couldn’t afford it by cutting entitlements. This seems like a winner, if you can pry political power from the cold, dead hands of the retiree lobby. But is it?

There are two major groups13 that would benefit from this, those being already-stable couples with children deciding whether or not to have another (e.g., going from 2 to 3), and the American underclass, in which single-motherhood and reliance on welfare is already the norm. The extra money will not help people who want to enter a stable relationship before having kids do that, and it might even hurt them (since they’ll be paying higher taxes).

This incentive would be far stronger for the underclass, because of their negligible earned income and because they put much less effort into raising their kids than stable married families do. Measured in approximate market value, the US underclass already gets half or more of its income from government programs.

But cash is much more valuable to this group than in-kind government benefits like food stamps or Section 8. (Hence phenomenon of using EBT cards to buy staples, then re-selling those staples for a fraction of the cost and using the money to buy luxuries.) The lump sum proposal essentially involves offering a decade or more earned income to this group for having a kid. If the government did this, you would see a subculture of women having a kid for the check, immediately blowing the money, and then having another kid next year. Having a dozen kids, not really raising them (someone will take care of it, since we don’t let kids with negligent parents go hungry), and living like a millionaire, would be a genuine lifestyle for some women.

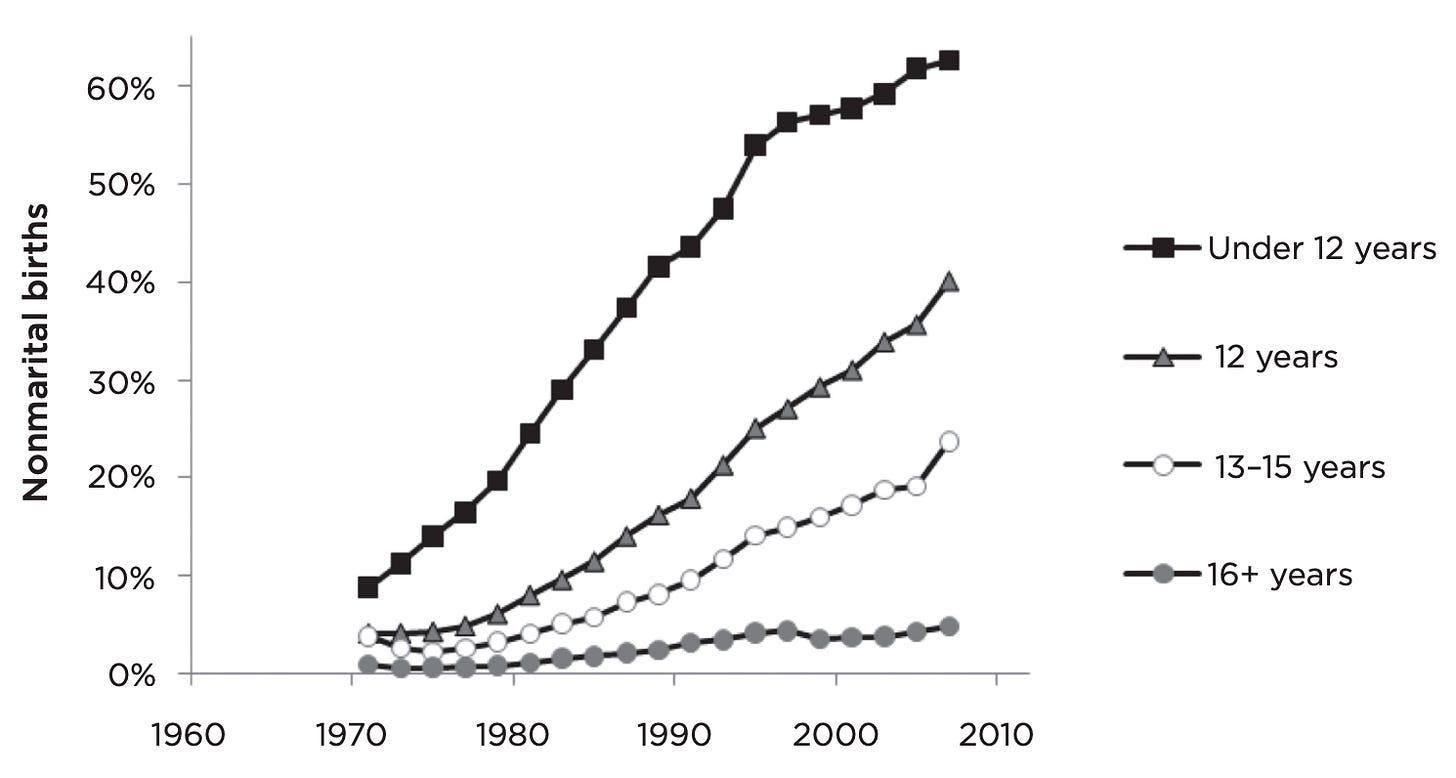

The silver lining of the worldwide post-2012 fertility decline is where it’s concentrated. The strong negative SES-fertility relationship characteristic of the demographic transition is flattening out and possibly even reversing in some countries because lower-class, less-educated women are much less likely to get married or enter long-term stable relationships.

This means that while dysgenics is still ongoing both between and within countries, it is not nearly as bad as it used to be. But that could easily be reversed by giving out large unconditional sums of money for children.

This is not idle speculation. Underclass women14 having children for the benefits (and underclass men living off of a mix of their girlfriend’s baby money and petty crime) used to be common enough to motivate Bill Clinton’s bipartisan welfare reform. Before this reform, the US government paid poor mothers large sums per kid. The average Aid for Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) payment in 1994, after state-level cuts had already begun was $420/month ($918/month in 2025 dollars), enough for non-working poor families to have similar incomes to working ones, especially in heavily-black areas.

These children were generally not well taken care of, requiring additional government programs to raise, to say nothing of the large criminal element. And an immediate $200,000 check is enormously more generous than the figure above.

There’s some evidence that the 1996 welfare reforms had no effect on fertility, but a priori that’s unlikely (and indeed, if giving parents money doesn’t lead to at least slightly higher fertility, political pro-natalism is dead in the water). The solution to this puzzle is that prior state level reforms and media campaigns led to widespread expectations (~61% of black women) that welfare would soon be ended (Clinton ran on ending welfare in 1992). Hence fertility in the relevant subgroups began its downwards trend before the 1996 federal law.

Huge, unconditional cash benefits for children could work in countries with no racial underclass or culture of single motherhood, like South Korea or Japan. But the likely effect in the US or most Western countries would be a return to the 1980s, when dysfunctional people had enormous numbers of net-negative children. Needless to say, this would be bad for the state finances and everyone else. It would make France’s current pro-natal policies, which boost fertility among unemployed Arabs and Africans, look pro-eugenics. A similar racial fertility gradient as existed in Latin America in the second half of the 20th century would likely develop.

I worry that many pro-natalists know and understand why an extremely fertile underclass is a bad thing, but that the taboo against racism stops them from addressing this directly. Hence we begin to see proposals that would only work if egalitarianism were actually true… but in the real world, where it isn’t true, they would be a disaster. I also worry that some pro-natalists are starting to view maximizing the number of people physically on Earth without regard for who they are as a goal in and of itself — they see an Age of Malthusian Industrialism as something to strive for. This will become more of a problem as the movement picks up political steam.

A slightly different version of this article was published here.

Arctotherium is an anonymous writer interested in demographics and the future of civilization. You can find more of his writings at his blog Not With A Bang or at his Twitter.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

I am amazed at the number of people who cite low Iranian fertility as evidence that feminism, secularism, or education are irrelevant, apparently not knowing about this very successful population control campaign, or that the Iranian population is very secular, Iranian women outnumber men in higher education (more than 60% of the total, rising to 70% in engineering), and Iran has one of the highest education-to-workforce ratios in the world.

Which is not the same as saying it doesn’t work at all. But I can’t help but notice that the big successes touted by professional pro-natal activists are things like “fertility still collapsed, but TFR was 0.1-0.2 higher than the counterfactual.” Even this is likely overstated because of the standard pro-intervention bias you find in most academic studies and because most papers look at short-run effects. Pro-natal programs tend to “fade out” because they pull births forward without changing cohort fertility as much you’d expect by looking at TFR or birth rate changes. Contrast this with anti-natalists reducing the TFR from 6 to 2 in 20 years in Iran, or Nazi Germany raising it from 1.6 to 2.6 in a decade.

Israeli fertility is often held up as exceptional and credited to a nationalist and pro-natalist state, but that’s not really true. The fertility of Israel’s various streams is about what you’d expect based on similar groups elsewhere. Israel just has by far the highest fraction of “breeder cults” (ultra-Orthodox Jews), serious patriarchal Abrahamic religious groups (religious Zionists), and religious Middle Easterners (Mizrahi, Arabs). A Netherlands that was 15% Amish, 10% orthodox Calvinists, and 50% Arab would be similar. Secular Israeli Jews have higher fertility than most similar groups (TFR = 1.9), but not substantially higher. This is about the same as Iceland or South Dakota, and probably increased by cultural spillover from the religious.

Orthodox Judaism is costly and difficult to practice. Even in its non-ultra-Orthodox form, it’s far stricter than most other religious groups, in a way not captured by conventional metrics of religiosity like worship attendance.

You can see shades of this worldview in intellectuals who argue for immigration on the grounds that immigrants are superior subjects to their native counterparts because of their lower crime rates, higher marriage rates, stronger worker ethic, and higher educational attainment, and that increasing the number of subjects increases the power of the state, allowing us to “beat China.” These arguments are not factually correct. Educational attainment in and of itself is bad, immigrants don’t work harder and aren’t more productive than their American counterparts, and immigrants’ descendants regress to their racial means in the United States in terms of both crime and marriage. But even if they were factually correct, this line of argument would still reflect the mindset of an oriental despot or Russian Tsar rather than a self-governing citizen.

Note that organic does not necessarily mean popular. The 60s changes were not popular in the West until they happened — but they weren’t imposed by a dictatorial oligarchy.

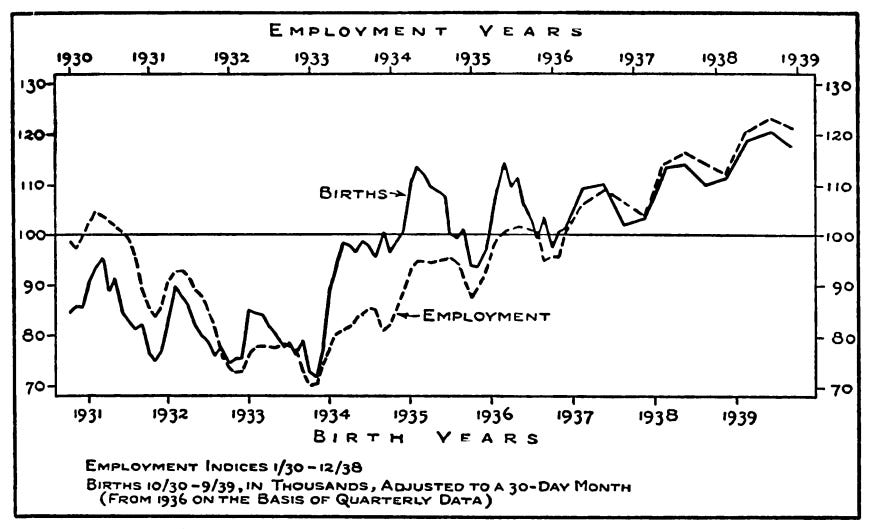

This is also why I don’t think Nazi pro-natalism, which was very successful, is a good example to draw from. The Nazi program combined marriage loans (with 25% forgiven per child), abortion bans (in Weimar Germany the most common method of family planning), increasing male employment through military Keynesianism, and the cultural promotion of motherhood. German TFR rose from 1.6 to 2.6 from 1933 to 1940. It’s hard to disentangle exactly which policy was most important, but given the similar (though much smaller) rise in Sweden in the same time period, and the rise in fertility as countries exited the Depression in the late 1930s, my belief is that the Nazis effectively started the postwar Baby Boom a decade early by increasing male employment. This would not have worked if the factors that connected male employment to fertility were taken away, as they were with second-wave feminism between 1963 and 1973. Eastern Bloc pro-natalism, while less successful, was starting with a less advantageous social situation much more comparable to modern states.

And depending on the course of technology, it may never matter. The singularity renders fertility concerns, along with everything else, irrelevant. My gut feeling is that it will probably (>50%) render the question moot, but since I can neither predict nor control this, I’d rather write about the base case where neither happens.

I’m a little surprised that Switzerland, which did not have a quarter of the relevant cohort of men killed in WWII, was so similar to Germany and Austria.

Though timing matters. If you have two populations with the same life expectancies and completed fertility, but population A has its kids earlier, population A will be both larger and younger at any given point. Both cohort fertility and TFR are useful for different purposes.

This Romanian source claims the tax was later raised, but doesn’t give details or numbers, and the cited subchapter of the book (Politica Pronatalistă A Regimului Ceaușescu II Instituții și practici) does not exist, at least in the Internet Archive version I found. I’m not sure if the citation is fabricated, a different edition of the book or something else. Multiple English-language sources claim the tax was 30% on income, but all of them cite this 1987 journal article, which appears to have made the number up. If anyone knows for sure and can send me a primary source, I’d appreciate it.

This is exacerbated by the fact that public sector and quasi-public sector jobs (created by regulation or state pushes for higher female employment) tend to be female-dominated. (This is not to say all public sector jobs are useless, only that a simple analysis of taxes paid and benefits received will make public sector jobs look better than they should.)

Plus extremely fertile ethnic subcultures, like Haredi Jews, the Amish, and Somalis. Frankly, I would not be happy about paying $2M to each Somali family in Minneapolis so they can have ten kids each. Haredim and the Amish are less of a problem, but that’s still a lot of money.

Lest I be accused of being racist: this was not just a black phenomenon, as Charles Murray’s Coming Apart is at pains to document. Lest I be accused of being anti-racist: in the 90s, this was first and foremost a black phenomenon, with a significant fraction of Latin Americans.

"Communist governments saw their people as tools of the state, not individuals and citizens valuable in-and-of themselves" – unlike Capitalist governments that see their people as tools of rich individuals, not people and citizens valuable in themselves?

Thanks for the interesting article.

The stupidest thing a country can do to increase its population is to allow the immigration of diverse people.