What explains the black–white homicide gap?

The common theories are incomplete at best.

Written by Noah Carl.

The brutal and racially motivated murder of Iryna Zarutska, a Ukrainian refugee, has brought the issue of black crime back into the public eye. As numerous commentators have been reminding us, black Americans account for a disproportionate share of the country’s violence.1 When it comes to murder, their age-adjusted victimisation rate is about eight times that for white people. (Because homicides are overwhelmingly intra-racial, victimisation rates are a good proxy for offending rates.2) And this disparity has been remarkably consistent over time: as far back as the 1920s, the black homicide rate was at least seven times higher. What explains it?

We can begin by dispensing with liberals’ preferred explanation, poverty, which has been thoroughly debunked. In short, when you analyse homicide rates at the fine-grained level of US counties, percentage black is just about the strongest predictor, and its effect size remains very large even when controlling for poverty and other factors.3 Poverty also doesn’t really make sense as an explanation: why would being poor cause you to go out and kill someone? In earlier centuries, it was elites who were most violent. Nor do the temporal trends add up. The US murder rate skyrocketed in the 1960s when poverty was falling. It then nosedived in the 1990s despite poverty flatlining. In fact, the murder rate was higher in 1990 than it was in 1900—when about 90% of the population lived in poverty by today’s standards. Plus, studies that try to disentangle cause and effect find little evidence that growing up poor makes people commit crime.4

Conservatives’ preferred explanation, family breakdown, isn’t substantially better. Once again, percentage black remains a very strong predictor of the homicide rate when you control for single motherhood. And the big drop in violence during the 1990s didn’t coincide with any major changes in family structure. By 2010, the murder rate was as low as it had been in 1960—when only 20% of black children lived in fatherless households (compared to more than half today). This doesn’t mean family breakdown has no impact on homicide, since different factors may have caused the rise and subsequent fall, but it does suggest it’s less important than commonly assumed. There is also evidence that children who grow up without a father because their father died do not have the same problems as those who were abandoned. Which suggests that absence of a father in the household isn’t the causal variable.

At this point, some readers are probably thinking, “I know what you’re going to say: IQ is the real explanation”. Actually, no. What’s interesting about the black–white homicide gap is that IQ cannot explain most of it. Yes, people with lower IQs are more likely to engage in violence, and black Americans have a lower average IQ. But they commit homicide at much higher rates than you’d expect from their average IQ.5

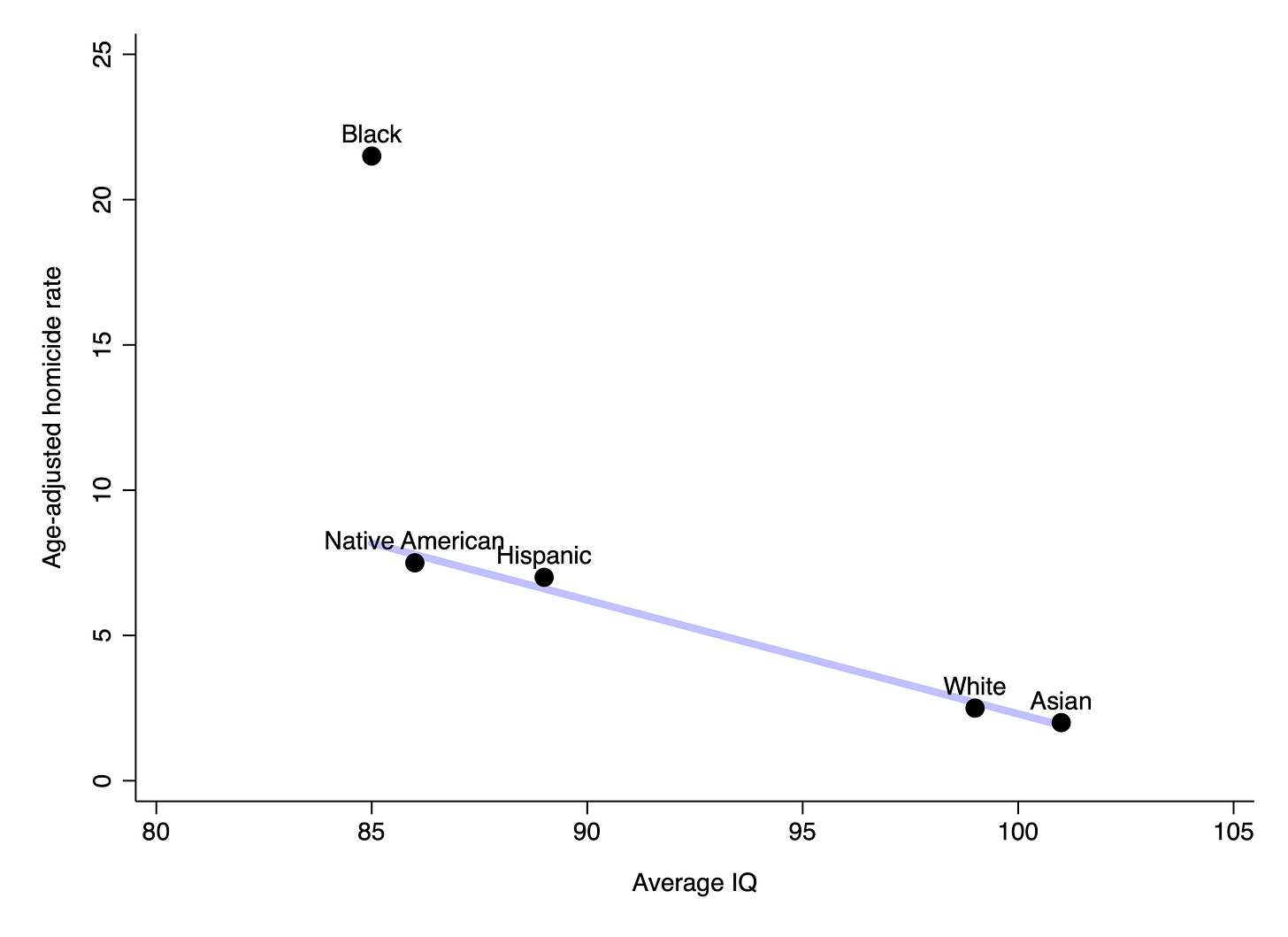

The chart below plots the relationship between average IQ and age-adjusted homicide rate across the five major “racial” groups in the US.6 The blue line shows the relationship among the four groups other than blacks. It predicts that blacks should have a homicide rate of around 8 per 100,000. Their actual rate is over 20 per 100,000. According to this (admittedly crude) analysis, IQ can only explain about 30% the black–white homicide gap.

About the numbers: age-adjusted homicide rates were taken from the CDC. They correspond to the year 2007, the latest I could find with data for all five groups, though this shouldn’t matter as the ratios are fairly constant over time. Average IQs were taken from Race Differences in Intelligence by Richard Lynn. Other datasets point to slightly higher figures for Native Americans, Hispanics and Asians, yet Lynn’s are consistent with NAEP scores from the relevant time period.7 And while higher figures for Native Americans and Hispanics would increase the slope of the regression line, a higher figure for Asians would pull it down. Even if the chart’s prediction for the black homicide rate is slightly too low, it’s unlikely that IQ explains more than 35% of the black–white gap.

Note that the very same pattern is seen in Britain. Black people commit substantially more violent crime than Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, despite having similar average IQs. It is also worth noting that poverty and family breakdown are at least partly downstream of IQ. So the portion of the gap explained by those two variables necessarily overlaps with the portion explained by IQ.

What else, then, could explain the gap? I am aware of three possibilities.

The first is testosterone. We already know that men commit vastly more violent crime than women and that many differences between the sexes can be traced back to men’s higher testosterone levels. It therefore stands to reason that any racial group with higher testosterone levels would also commit more violent crime. Lee Ellis reviewed the evidence in 2017, and found “modest support” for the theory that testosterone explains racial differences in violence. While testosterone does predict violent crime, and blacks do have higher testosterone levels than whites, these generalisations may not hold for every measure of androgen exposure.

The second possibility is traits relating to anti-social personality, including aggression, impulsivity and lack of remorse, which may reflect faster life history. Lynn is the foremost proponent of this theory and he presented some evidence for it in a provocative 2002 paper. (This was followed by a book in 2019, which I haven’t read.) Lynn notes that blacks score significantly higher than whites on the psychopathic deviate scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, with whites scoring significantly higher than Asians. Blacks also have higher rates of conduct disorders and ADHD.8 However, some of these differences are relatively modest. For example, the average black–white gap on the psychopathic deviate scale is only d = 0.40. On the other hand, differences at the mean are magnified in the right tail—the part of the distribution from which criminals are drawn.

The third possibility is culture. Over the years, various scholars have argued that black crime stems from a “culture of violence”, perhaps similar in nature to the culture of honour that prevails among whites in the American South. A recent example can be found in a 2020 essay by Lawrence Mead, which was retracted following a scurrilous petition signed by hundreds of academics that accused him of “explicit racism”. (His essay did not even mention genes.) The main problem with this theory is the fact that black people are disproportionately involved in violence not only in the US but in other countries too, and it would be rather surprising if the same culture had arisen independently in all these separate places.

Which explanation is correct? Based on currently available evidence, it’s hard to say for sure. And of course, the various possibilities are not mutually exclusive. For example, differences in testosterone may be partly mediated by differences in anti-social personality. In all likelihood, every theory mentioned in this article has a grain of truth in it (with poverty being the least important). The key point is that conventional theories are insufficient.

Noah Carl is an Editor of Aporia.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

It goes without saying that I am not blaming all black people for violent crime. I am simply discussing statistical disparities.

The ratio of victimisation rates is similar to the ratio of offending rates. Discussion tends to focus on victimisation rates because they are based on high-quality data from the CDC (rather than patchy data from the BJS).

The sons of black families in the top 1% of the income distribution are incarcerated at the same rate as the sons of white families at the 33rd percentile. In other words, black men from the richest families in America commit serious crimes at the same rate as white men from families who are poorer than two thirds of Americans.

A study of Swedish lottery winners observed zero effect of parental wealth on children’s delinquency.

In The Bell Curve, Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray found that blacks were 2.5 times more likely to have ever been incarcerated than whites—even when holding age and IQ constant.

I put “racial” in quotes because Hispanics, Asians and to some extent blacks are groups of mixed ancestry.

Lynn’s figure of 89 for Hispanics is also consistent with the 2001 meta-analysis by Philip Roth and colleagues.

Plus, they have higher rates of psychotic disorders like schizophrenia.

“What else, then, could explain the gap? I am aware of three possibilities.” …”Which explanation is correct? Based on currently available evidence, it’s hard to say for sure. And of course, the various possibilities are not mutually exclusive.”

This. I’ve seen your posed quandary in many forms during my entire career in academia. The problem is indeed “multi variate”. To continue to look at the “problem” and ask “which *one*?” is fruitless and leads to confusion. The answer is simply, there is no single cause, nor will society addressing any single cause solve the “problem”. This is why society is still confused and stymied to this day wrt the “Black problem”. Every effort to alleviate Black pathology has assumed a single cause to be addressed and therefore (predictably) failed miserably. We as a species just are not equipped to handle/conceive of such multi variate phenomena, much less address such pathology.

If IQ correlates with crime, and only a minority of blacks commit the most heinous crimes, and this minority likely has IQs even lower than the black average (and maybe even higher testosterone), plus the culture that a very low IQ group of fatherless teens would create (a kind of downward spiral), would that get you your answer? Even an “unproven” theory (as per Popper, no evidence can “support” a theory) can still be a very good theory—especially if the alternative theories have been tentatively falsified.