Pinker is wrong: We should "go there"

In his new book, Steven Pinker steel-mans the case for not discussing race and IQ. He isn't persuasive.

Written by Bo Winegard.

Few topics inspire bad arguments as reliably as race differences in intelligence. So often have I responded to them that I have plausibly been accused of obsession. But as long as the bad arguments persist, someone must respond. Consider it a public service.

The latest comes from Steven Pinker’s new book, When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows… It deserves attention precisely because it comes from Pinker, a celebrated academic and an outspoken defender of free speech and open inquiry. This is not some indignant progressive who made a career of castigating “racist pseudoscience”, but a rational centrist who has long argued against the left’s denial of human nature.

Pinker announces that he is presenting “the best case I can think of for limiting intellectual expression,” so we shouldn’t necessarily take the ensuing argument as his settled view. Even so, at least one fellow skeptic, Michael Shermer, said on his podcast that he was “pretty convinced by the argument.” Whether Pinker agrees with it himself, it evidently persuaded at least one other person and thus deserves scrutiny.

Pinker concedes at the outset that he “cannot muster an argument for censorship or punishment.” What he can do, however, is “envision a case for a different policy: don’t go there.”

But what, in practice, is the difference between censorship and refusing to “go there”? Pinker’s answer is that “everyday social life” offers a model “in which we leave some observations unstated”. There is, after all, no law against brusquely announcing that someone is fat, yet most of us refrain from doing so because it would be rude and boorish. Much of civilized life, in fact, is maintained by tactful evasions, euphemisms and silences.

True enough. But let us press the analogy. Suppose that in a university seminar on intelligence someone states, “On average, whites score higher on IQ tests than blacks, and some researchers believe this difference is partly genetic.” Would he be expelled from the class? Surely not. If he instead asserted, “The girl in the front row is morbidly obese,” he certainly would be, even if his claim was true. It is therefore difficult to see how “everyday social life” offers a useful model here.

Pinker wishes to avoid endorsing censorship even hypothetically, yet the suppression of discussion about race and IQ demands precisely that—if not formal sanctions, then at least social punishment. How else could we stop motivated researchers from pursuing the topic or firebrands from discussing it? One might as well support a voluntary moratorium on pornography or Quentin Tarantino movies. A policy of silence, of “not going there”, requires something more than private disapproval.

Pinker proceeds to quote a passage from Noam Chomsky, which I reproduce because it is central to his case:

Given the virtual certainty that even the undertaking of this inquiry will reinforce some of the most despicable features of our society, the seriousness of the presumed moral dilemma depends critically on the scientific significance of the issue that [the researcher] is choosing to investigate. Even if the scientific significance were immense, we should certainly question the seriousness of the dilemma, given the likely social consequences. But if the scientific interest of any finding is slight, then the dilemma vanishes …

A possible correlation between mean IQ and skin color is of no greater scientific interest than a correlation between any two other arbitrarily selected traits, say, mean height and color of eyes … In the present state of scientific understanding, there would appear to be little scientific interest in the discovery that one partly heritable trait correlates (or not) with another partly heritable trait. Such questions might be interesting if the results had some bearing, say, on some psychological theory, or on hypotheses about the physiological mechanisms involved, but this is not the case … It would be foolish to claim, in response, that “society should not be left in ignorance.” Society is happily “in ignorance” of insignificant matters of all sorts.

Pinker adds that “the major possibility for harm” lies in the prospect that “people might be tempted to use [such findings] as Bayesian priors in their treatment of individual African Americans, unjustly putting them at a disadvantage.” I will return to this supposed cost in a moment.

It is not entirely clear that Pinker endorses Chomsky’s reasoning, since he later acknowledges the serious difficulties inherent in maintaining a policy of genteel silence about race differences. Nevertheless, because he cites Chomsky approvingly before noting the limits of such self-imposed ignorance, the passage warrants closer scrutiny.

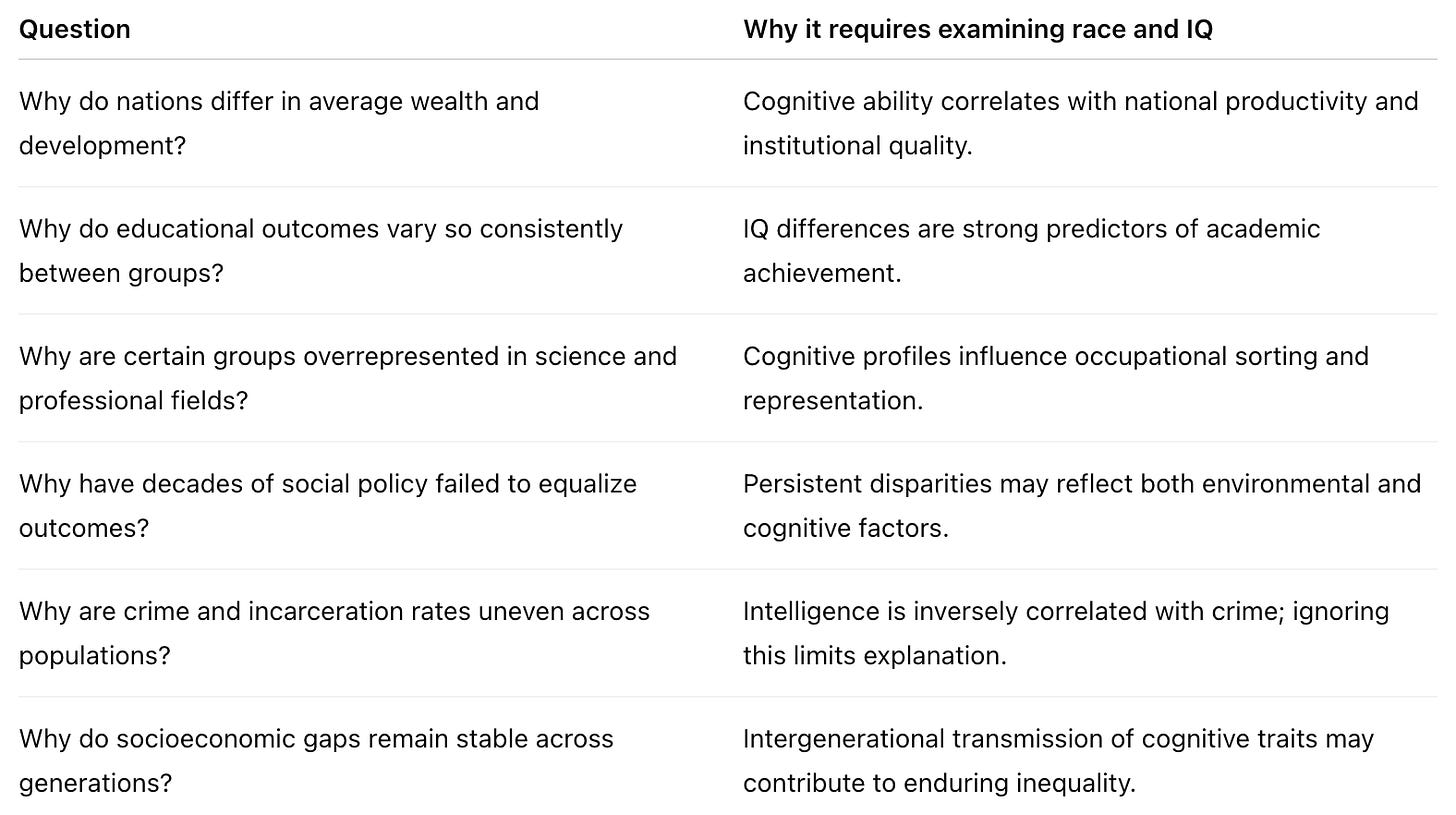

The central flaw in Chomsky’s argument is his claim that the relation between race and intelligence holds no more scientific interest than the correlation between any two arbitrarily chosen traits. Race is both a biological and social reality, a product of evolutionary history and a salient marker of human identity. Intelligence, as measured by IQ, is strongly predictive of life outcomes, including educational attainment, income, rates of violence, and even marital stability.

Differences in mean IQ scores between populations therefore bear directly on questions of social inequality and public policy. To claim that these disparities are somehow trivial or uninteresting is absurd. What is more, refusing to study them precludes any serious explanation of persistent group differences in achievement, an omission that inevitably invites ideology to fill the gap.

Suppressing discussion of race and IQ is thus like spewing an epistemic smog into the intellectual atmosphere. It makes it impossible to answer (or even to address) many important questions. Why is Europe wealthier than Africa? Why are whites more likely to be professors than blacks? Why are Jewish people more likely to boast outstanding achievement than gentiles? And on and on.

The wider point is this: you simply cannot see the world clearly if you do not understand racial differences. Race and IQ is not some trivial correlation such as that between foot size and height. It is of vast significance for anybody who wants to understand reality.

Moreover, promoting this elevated form of ignorance about race differences in intelligence will not stop progressives from speaking or obsessing about race. It will merely allow their theories of racism to prevail unchallenged in a distorted marketplace of ideas. In effect, Pinker’s counsel resembles that of a besieged general who, in the name of decorum, lays down his arms and allows the enemy to plunder his city.

Consider one example of what might happen in this world of voluntary silence. A liberal professor points to enormous outcome disparities between blacks and whites, arguing that these disparities are dispositive proof that America is pervaded by racism. A conscientious student, Tiffany, who had loved America, feels disheartened. The disparities really are alarming. She asks advice from her psychology professor, Robert. But what if Robert has embraced the notion of a genteel silence about race differences in intelligence?

Tiffany: I learned in my sociology class that blacks are paid much less than whites. They are also more likely to be homeless and incarcerated. Is this not evidence that America is racist? What else might explain it?

Robert: I don’t think anything edifying can possibly follow from discussing race differences. We should try to ignore them and focus on individuals.

Tiffany: Well, ok, but how do we explain these huge differences? My professor said that the country is racist and that Ibram X. Kendi was right all along. I don’t want to believe that, but how else am I to make sense of these differences? Why do white people get paid more? Is there really white privilege? Are whites holding blacks down?

Robert: To the best of our ability, we should focus only on individuals. Once we think about groups, we get lost in a divisive conversation.

Tiffany: What could be more divisive than the reality of widespread racism in the country though!

Robert: If we must address this, perhaps cultural differences between groups is to blame.

Tiffany: You mean that black culture is worse than white culture?

Robert: Let us not say “worse.” Let us say different.

Tiffany: But if it leads to less money and more incarceration, surely it is fair to describe it as worse. And if it is worse, why do blacks not absorb the superior white culture?

Robert: It’s really just different. But let us not trouble ourselves with these things. We should treat people as individuals and not worry about group statistics. Those are meaningless.

Tiffany: This is impossible. How can I ignore this? My country might be beset by racism. Doesn’t that matter to you!?

I cannot imagine any curious person being satisfied by Robert’s answers. The embrace of silence, however, would produce millions of Tiffanys searching for explanations and absorbing the only one readily available, i.e., the one that attributes every disparity to racism. The result would be deepening distrust of the nation, growing animosity toward the status quo, and the conviction that liberalism itself is merely a patina over an unjust system of racial exploitation.

And this is all to preempt what Pinker describes as the “major possibility for harm” from discussing race and IQ, namely that people might use demographic information as Bayesian priors when assessing individuals. But this is not, in fact, an unequivocal harm. Should people not be allowed and sometimes even encouraged to use demographic data to inform their priors? I think so, though I admit the issue is somewhat tricky.

Let us begin with a reasonably uncontroversial example. It is past midnight in a seedy hotel. A woman is alone, making her nightly journey to work. As she walks down the corridor, she notices an elevator standing open. If she hurries, she can catch it. Inside are either two men or two women. Should she be indifferent to the sex of the occupants, maintaining equal priors about her safety? Most people, I suspect, would not only understand but endorse her use of demographic cues in assessing risk. If two men, she might wisely hesitate; if two women, she might hurry.

What if we change the example to two white men with scrubby clothing and tattoos, or two Asian men in suits. Again, I suspect most people would recommend using demographic (and class-based) cues. But what if we change the example to two black men or two white men. Suddenly we pause. It just seems wrong to judge individuals based on group characteristics! On the other hand, it also seems wrong to tell a woman that she must, in the name of decency, ignore base rates. Wrong and illiberal. Wrong and Orwellian. Like a war on noticing.

Here we encounter a conflict between two otherwise commendable principles. The first is that we ought to treat people as individuals; the second, that we are entitled to observe the world and use all available information when making decisions. However, the latter is difficult to reconcile with a strict version of the former, since demographic information often provides useful predictive clues—at least until more specific, individual data become available.

A reasonable compromise is that individuals may, and indeed should, use demographic information to form Bayesian priors, while institutions may not. I may choose, for instance, to walk down a street populated by women rather than one populated by men without violating any essential liberal norm. But an institution cannot, on the same logic, hire a woman over a man on the basis of demographic averages.

This is not an ideal compromise, since it would inevitably lead to less accurate decision-making. But that is a question for another essay. The important point here is that the great harm Pinker hopes to avoid is no harm at all. Indeed, the reverse is more plausibly true: it is immoral to possess knowledge of group differences (as Pinker surely does) yet conceal it from the public so that, in their ignorance, they are deprived of the information needed to make rational decisions.

In a curious passage, before conceding that the case for “not going there” is riddled with difficulties, Pinker contends that “deciding to leave certain questions unanswered is not anti-intellectual, because it would itself be justified by reasoned argument.”

I don’t doubt that refraining from inquiry can sometimes be defended by reasoned argument (as can almost anything) and it is true that many Christian thinkers once warned against the dangers of idle curiosity. But that does not make the stance any less anti-intellectual. In 1854, one could have reasoned with Charles Darwin that the theory of evolution was “dangerous” and that ignorance was preferable to knowledge. Perhaps such reasoning could have been persuasive; it would still have been anti-intellectual.1 Communities in which people voluntarily abstain from attempting to explain the world are indeed best described as anti-intellectual, even if they arrived at their norms through rational argument.

Pinker concludes by supporting color-blind policies in public and private:

As the writer Coleman Hughes has argued, there are good reasons for even the most open-minded people to want to keep the issue of race and intelligence out of mainstream conversation. But that tacit agreement should be a part of a larger commitment to color-blind policies in public and private life.

I am ambivalent about the wisdom of color-blind ideology, but the most obvious objection to this passage is that there is no reason to expect the left to stop obsessing over race anytime soon. Thus, the argument would be like saying that “defund the police” is a good idea so long as we all refrain from committing crimes.

Since color-blindness will not happen in contemporary America, we must face reality as it is. And in this reality, the left will continue to talk about race and to blame racism for widespread racial disparities. Like others who have recommended silence about race differences, Pinker does not tell us how we should respond. But a kind of gentlemanly silence seems utterly inadequate.

Before concluding, I should note a point of agreement. Pinker is not entirely wrong. Discussing racial differences in intelligence and other socially valued traits is incendiary, and in many contexts inappropriate. The social norms that restrain such discussion are not arbitrary. Race is contentious because multi-racial societies are fragile, perpetually threatened by resentment and conflict. I do not think that a politician should casually joke about racial differences in intelligence.

Yet in certain contexts, judicious conversation about these differences is not merely permissible but necessary. Diversity is here to stay, and we must learn to live with it. Part of that task is learning to discuss it honestly. If we do not supply accurate answers to serious questions about racial disparities, the left will gladly supply inaccurate ones. And if those answers become dominant, many will come to believe that liberalism itself is nothing but a procedural disguise for white supremacy, and they will become avowed enemies of liberalism. I do not think liberalism can endure many more enemies.

Pinker might very well agree with this, for it is worth keeping in mind his argument for silence was, as he wrote, an attempt to steel man the case against untrammelled free expression. At any rate, it is comforting for those of us who recommend candor to know that even someone as bright as Pinker struggles to make a compelling argument against honesty about race differences.

Bo Winegard is Editor of Aporia.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

To be clear, it’s perfectly rational to prefer to live in an “anti-intellectual” community. But it’s still anti-intellectual.

Studying race differences (even in relation to IQ) doesn't make one a racist or supportive of racism any more than studying sex differences makes one a sexist or supportive of sexism. Only through understanding the true causes of differences can we get away from the blame game being pushed by critical race theorists.

Bo, thanks for an excellent rebuttal to Pinker's stand on IQ and race. I have been an admirer of Steven Pinker, and I find his recent stand puzzling.

"Race is both a biological and social reality, a product of evolutionary history and a salient marker of human identity. Intelligence, as measured by IQ, is strongly predictive of life outcomes, including educational attainment, income, rates of violence, and even marital stability."

These points are demonstrably true, and I would expect any rational, logical-thinking person to concur. Therefore, I suspect a political ideology narrative is involved.

"Since color-blindness will not happen in contemporary America, we must face reality as it is."

This is the case not only in America, but throughout Western Civilization, Asia, and even sub-Saharan Africa.