Written by Bo Winegard.

I am haunted by the fear that progressives more clearly understand race than mainstream conservatives. By this, I do not mean that they accurately grasp the nature of race differences or correctly diagnose the causes of race disparities. Rather, I mean that they comprehend the power, the importance, and the inevitability of race. And thus while conservatives have attempted to alleviate racial tensions by promoting colorblindness, progressives have eagerly exploited racial politics.

Coleman Hughes’s book, The End of Race Politics, confirms and deepens my fear. Lucid and engaging but rarely straying from Reaganite orthodoxies, it could serve as a philosophical manifesto about race for mainstream conservatism. Therefore, its failure to wrestle with the difficult and perhaps insuperable problem of race differences while promoting a superficially appealing but ultimately doomed vision of colorblindness is illustrative of more than a flawed book. It is illustrative of a flawed political movement.

Because the ideal of colorblindness is pervasive among conservatives and centrists, and even among many liberals, my criticism of it and of The End of Race Politics will undoubtedly rankle many readers. Certainly, I take no great joy in it. Ten years ago, with minor quibbles, I would have praised the optimism of the colorblind ideology. Now, I consider it a pernicious will-o’-the-wisp, alluring but implausible and therefore dangerous. Like other seductive ideologies, it cloaks with virtue its falsehoods and improbabilities. It doesn’t debate or persuade. It converts or it condemns.

In the twentieth century, conservatives, embracing their role as hardheaded realists, correctly resisted and ridiculed communism, perhaps the most seductive and venomous ideology ever conceived by man. But today, they embrace colorblindness and its inevitable consequences, e.g., rapid demographic change, widespread racial progressivism, and the demonization of anyone who resists. After all, in a colorblind world, drawing attention to racial differences or to the deleterious effects of demographic change is not just wrong, it is heresy. We may see race, and we may see that the racial composition of the West is changing, but we cannot discuss it. At least, not without an armory of euphemisms.

My hope in this piece, a critical review of The End of Race Politics, is to convince conservatives to reconsider their position.

Racial politics are inescapable because race is inescapable. Pretending otherwise might be expedient. But so too is putting a veneer over a decaying house. Alas, the illusion cannot last, and the house will eventually collapse. Reality is ineluctable. Best to confront it honestly.

DOES RACE EXIST?

Any assessment of the viability (and desirability) of colorblindness must begin with an assessment of race itself. For if race is merely a social construction, as the orthodoxy maintains, then its continued participation in our individual and social consciousness is unnecessary and likely undesirable. We can and should eliminate it as we eliminated other illusory social categories such as “warlock,” “werewolf,” and “possessed.”

However, if race is a real biological phenomenon and not just a bewitching illusion, then the project of colorblindness runs into immediate trouble. How do we prevent people from perceiving and discussing reality? And even if possible, is not such a goal as authoritarian as insisting that everyone publicly accept that 2 + 2 = 5?

Perhaps not. One could contend that race is real but that highlighting it, like highlighting a person’s unsightliness, is boorish and unseemly. After all, civilized people often keep unpleasant or embarrassing truths to themselves, understanding that social harmony requires tactful silence as much as it requires grace and charm. Moreover, in a multi-racial country like the United States, emphasizing race might incite racial anger and ruinous racial competition. Subduing racial tensions by abstaining from invidious conversations about race does not require a Stalinesque tyranny. It requires good manners and self-restraint.

Nevertheless, if race realism is correct, colorblindness is not necessarily a noble desideratum. At minimum it would require painful tradeoffs. For example, it would require self-imposed limits on discourse about a potentially important topic, and it would prohibit using knowledge about race differences to increase the efficiency of medicine, policing, and other social programs. On the other hand, if social constructionism is correct, then colorblindness is more obviously desirable since the only sacrifice it would require is the relinquishing of an illusion. We would lose nothing of empirical, political, or moral consequence.

Despite its popularity, the position that race is an arbitrary social construction is exceedingly implausible—perhaps even absurd. Without examining the underlying genetic evidence, one can easily perceive that human groups are different from each other in predictable, patterned ways. Denzel Washington belongs to one group (blacks); Paul Newman to another (whites); and Bruce Lee to yet another (Asians). This takes no expertise and requires only a functional human brain and the appropriate concepts (which would likely develop in any culture). Racial categorization results from natural cognitive and emotional predispositions because human populations differ from each other in reliable, correlated ways.

This is not the end of the story, of course, and social constructionists have forwarded a variety of arguments against the commonsense view of race adumbrated here. Nevertheless, it does illustrate that a strong version of social constructionism is counterintuitive, at best.

Recognizing the implausibility of the social constructionist perspective, Hughes positions himself as a reasonable centrist eschewing extremes on both sides:

“The concept of race falls into a third category. It’s neither completely natural nor completely socially constructed. It’s a social construct inspired by a natural phenomenon.”

This is a common strategy in the race debate. One first accepts, even embraces, the reality of human variation. But one quickly contrasts it with a caricatured version of race realism which views races as pure and primordial—perhaps even the product of separate creations. This grotesque parody of race realism is then ceremoniously denounced and repudiated. The virtuous center remains, its wisdom and righteousness affirmed by the odiousness of its alternatives.

The point is to reject and stigmatize race realism and its inconvenient consequences without endorsing arrant nonsense such as that human populations are the same or that group differences are only literally skin deep. (This was once a common saying and is still common enough, though it is obviously untrue.) Thus those who pursue this strategy often disregard human variation in practice (if not in profession) and form an alliance with social constructionism which maintains the appearance of intellectual respectability but which ultimately denies and/or ignores the importance of race differences.

Hughes pursues an abridged version of this strategy, one that is admirably free of ad hominem attacks. In fact, Hughes only explicitly mentions “race realism” (actually “race realist”) once and in the appendix. Thus his position is often only contrasted with an implicit variant of race realism, which, being implicit, he does not denigrate. (Though he does mischaracterize “hardcore race realists” as believing that there are “hard-and-fast distinctions between the races.” Most race realists have never believed such a thing.)1

He writes:

“All the foregoing examples illustrate that the race categories we’ve created are arbitrary—not only with respect to science but also with respect to the social policy objectives they are used for. Yet despite that arbitrariness, these categories have a huge impact on people’s lives.”

And:

“The arbitrariness of race is not a fixable problem. It’s built into the very act of classifying people by race.”

But if race is not “completely socially constructed,” as Hughes contends, then how is it arbitrary? The answer is not entirely clear, but it seems to stem from Hughes’s view that “real” categorizations require “sharp lines” which are not available for races. At the beginning of his discussion of race, he argues:

“In science, for instance, our goal is to describe nature. So we develop concepts and categories that map onto nature as closely as possible, such as the concept of a tree or the concept of mass in physics. These are natural concepts—concepts that map onto nature with great precision.”

Then he notes that race belongs to a third kind of category, one that is neither entirely a social construct nor entirely natural.

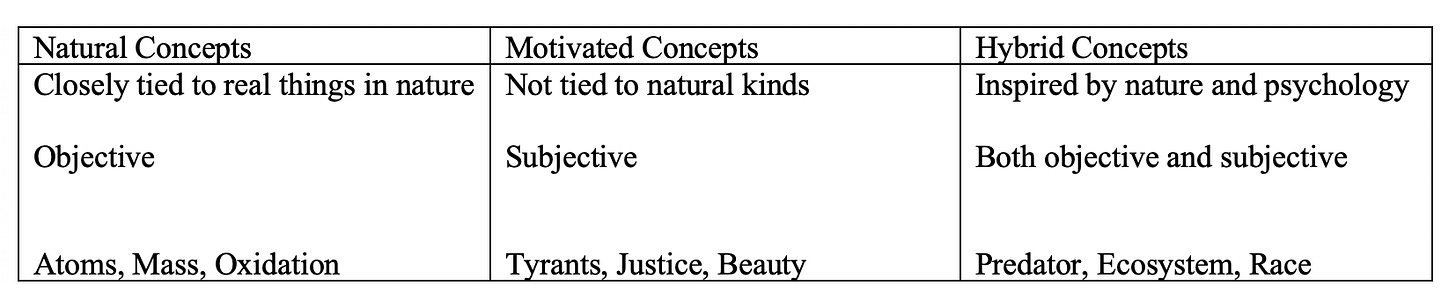

A charitable reconstruction of the argument seems to be this. Our classifications come in three major varieties: (1) those that are psychologically motivated; (2) those that are naturally motivated (i.e., what philosophers call “natural kinds”); and (3) those that are some combination of the two. An example of the first classification might be “tyrants,” a subjective category that could include anyone from Julius Caesar to Joseph Stalin to Idi Amin. An example of the second classification might be “copper,” an objective category that would include all objects composed of the chemical element copper with the atomic number 29. And an example of the third category might be “predator,” a fuzzy category that would include most animals that eat other animals, but whose boundaries might provoke debate and uncertainty, e.g., is a goldfinch a predator?

Race is a hybrid concept. It is not entirely socially constructed. Humans, after all, do vary and that variation is related to ancestral geography. But it is partially socially constructed. The U. S. census categories, for example, were not created after protracted study of biology or probing conversations with evolutionary theorists and population geneticists. Rather:

“These categories were created based upon a vague mix of intuitions about racial difference and political lobbyists attempting to sway the categorization in one direction or another.”

In the appendix of The End of Race Politics, Hughes offers a slightly more technical argument, contending that we can imagine three scenarios for human clustering (or races). Because this is his most carefully considered argument against race realism, it is worth quoting at length.

“Scenario A: Imagine a room full of people. Your task is to measure their height (inches) and weight (pounds), and plot the data on an x-y coordinate graph. But here’s the twist: the only people in the room are NFL linebackers and preschool children…

Scenario B: Now imagine performing the same experiment, but this time the room is filled with one thousand college freshman…

Scenario C: Now imagine performing the test again. This time, the room is filled with three groups: seventeen-year-olds, fifteen-year-olds, and thirteen-year-olds. When you plot the data, you faintly perceive that there are three natural [emphasis added] clusters, but you don’t know where you would draw the line between them…

…there are valid ways of clustering ourselves that broadly match the major out-of-Africa migrations and the lay concept of race, but those clusters overlap and bleed into one another to such as extent that it is not possible to draw an actual line between races that has any meaning in the real world. In other words, no real-life racial sorting mechanism could ever be justified on even purely scientific grounds (to say nothing of political or moral grounds).”

This makes the fallacious reasoning in Hughes’s dismissal of race realism clear. He contends that we perceive “natural clusters” but also that the actual lines we might draw between them have no meaning. This is clearly false. Claiming that “Seventeen-year-olds are taller and heavier than thirteen-year-olds” would be meaningful and it would be correct. This is the basis for creating age divisions for sports in high school. Seniors are not allowed to play on the freshman teams just as boys are not allowed (or perhaps I should write, “once were not allowed”) to play on the girls’ teams because we recognize that older athletes have physical advantages over younger athletes, on average.

At any rate, Hughes often contradicts his own claim that such lines would be meaningless. For example, he writes that:

“President Obama is the son of a white mother and a black father, so we categorize him as black.”

And:

“To qualify for certain government programs, for instance, someone needs to have one-fourth Native American ancestry.”

And:

“…the top-earning blacks earn 9.8 times as much as the lowest-earning blacks…”

If racial categories were meaningless, these sentences would be as perplexing as a Lewis Carroll poem. What could it mean, after all, to be the son of a “white” mother and a “black” father if those adjectives (based on meaningless lines drawn between phenotypic clusters) were meaningless?

Hughes’s underlying problem is a confusion about the nature of concepts and classifications that includes a misguided demand for clear demarcations that would, if consistently practiced, bring much of our science to a screeching halt. Many of our most useful categories, including race, are fuzzy with imprecise (and unclear) boundaries, more like family resemblances than essences without overlap.

Color is a good example. Because of the properties of our visual system, a small section of the electromagnetic spectrum is visible. This is a continuous spectrum, and the human eye can distinguish hundreds of thousands to millions of colors; however, owing to cognitive limitations, we generally do not attend to all these differences, and we do not classify color into hundreds of thousands of categories. Rather, we make practical distinctions, understanding that the specific lines we draw are always somewhat arbitrary, i.e., there is not a precise and unambiguous division between, say, orange and yellow or between blue and purple.

A more intuitive and enlightening example of a fuzzy category is the concept of a genre. Although genre is not a scientific concept, it is indispensable for film and literary analysis. There are many genres: horror, thriller, drama, comedy, romance, science fiction, western. And on and on. Often, we have no trouble putting a film or a novel into a genre. A Nightmare on Elm Street, for example, clearly belongs in the horror category, whereas The Big Lebowksi clearly belongs in the comedy category. But things are not always so simple. Where does Fargo belong? Is it a thriller? A drama? A comedy? Or maybe a black comedy? What about Silence of the Lambs? Is it a thriller? A horror film?

The point, of course, is that these questions do not always have unequivocal answers because genres are fuzzy categories—they can blend and bleed into each other. A slow moving and poignant drama can suddenly transform into an exhilarating action film, while a terrifying horror film can become a subdued philosophical reflection upon mortality.

Instead of accepting Hughes’s tripartite division of concepts and classifications, we should be more pragmatic, recognizing that all classifications are socially constructed since they are created by humans, even supposedly “natural kinds” such as zinc or copper. (The example Hughes gives of “tree” is an odd one since tree is not monophyletic and is quite fuzzy with no precise scientific meaning.) Some classifications, however, are more informative than others. For example, the category of “cattle” is more informative than the category “things with horns.” Similarly, “existential horror” is more informative than “comedy.”

Relatedly, we should recognize that the Socratic ideal of clear, coherent definitions without exceptions and of essences that divide nature at pre-established seams is a chimera in a post-Darwin world. Reality is a continuum, a gradated canvass not a paint by numbers with clear lines and pure colors. Our categories should (and often do) reflect this. And so long as they do, race realism is a perfectly reasonable position.

For race realism does not contend, as Hughes suggests, that human populations are wholly discrete and discontinuous. Nor does it contend that human populations are defined and distinguished by mysterious essences. It is not committed to Platonic metaphysics, obscurantism, or rightwing mysticism. It is no more esoteric or metaphysical than sex or species realism. In fact, it is a straightforward consequence of taking Darwin seriously.

It consists of the following propositions:

(1) Race is a biological phenomenon. Humans vary in patterned and predictable ways.

(2) Race is an evolutionary phenomenon. The patterns of human variation are largely caused by natural and sexual selection (and other evolutionary processes).

(3) Race is a psychological phenomenon. Races vary not only in physical traits but also in psychological traits.

Before considering The End of Race Politics in more detail, I should briefly defend these propositions since my embrace of race realism is the chief cause of my disagreement with Hughes’s book.

Earlier, I noted that ordinary people have no problem perceiving racial groups such as white, black, Asian, and Hispanic and categorizing people into them, e.g., Lebron James is black and Ryan Gosling is white. As we have seen, critics of race realism counter that these classifications, though apparently obvious, are in fact illusory because they do not accurately reflect the reality of human genetic variation. Or because they are inevitably arbitrary (see the above about fuzzy categories). But the evidence overwhelmingly contradicts the illusionist position. Genetic variation is related to ancestral geography which is related to social race (and self-identified race and ethnicity or SIRE). In fact, if not for the triumph of political correctness, modern intellectuals would likely celebrate the genetic evidence as an impressive vindication of early race theorists—the same race theorists they instead dismiss as bigoted cranks.

As Charles Murray wrote about Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza’s The History and Geography of Human Genes

“[It]… revealed for the first time that genetic differentiation of populations showed a continental pattern. …it was nonetheless jarring to see how closely the clusters corresponded with traditional definitions of races at the continental level. The five continents in question were Africa, Europe, East Asia, the Americas, and Oceania.”

Similar examples abound. Here are a few.

Noah Rosenberg and his colleagues wrote:

“At K = 5, clusters corresponded largely to major geographic regions.”

In another paper, he and his colleagues wrote:

“Examination of the relationship between genetic and geographic distance supports a view in which the clusters arise not as an artifact of the sampling scheme, but from small discontinuous jumps in genetic distance for most population pairs on opposite sides of geographic barriers, in comparison with genetic distance for pairs on the same side.”

Sarah Tishkoff and Kenneth Kidd wrote:

“The emerging picture is that populations do, generally, cluster by broad geographic regions that correspond with common racial classifications (Africa, Europe, Asia, Oceania, Americas).”

And as Bruce Lahn and Lanndy Ebestein noted, this pattern is not surprising because:

“Anatomically modern humans first appeared in eastern Africa about 200,000 years ago. Some members migrated out of Africa by 50,000 years ago to populate Asia, Australia, Europe and eventually the Americas. During this period, geographic barriers separated humanity into several major groups, largely along continental lines, which greatly reduced gene flow among them. Geographic and cultural barriers also existed within major groups, although to lesser degrees.”

What is more, this genetic variation corresponds to common racial categories in the United States (and elsewhere).

For example, Hua Tang and colleagues wrote:

“Numerous recent studies using a variety of genetic markers have shown that, for example, individuals sampled worldwide fall into clusters that roughly correspond to continental lines, as well as to the commonly used self-identifying racial groups: Africans, European/West Asians, East Asians, Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans…

We have shown a nearly perfect correspondence between genetic cluster and SIRE for major ethnic groups living in the United States, with a discrepancy rate of only .14%.”

Peristera Paschou and colleagues wrote:

“A complete leave-one-out validation experiment demonstrates that, using all available SNPs, assignment of individuals to their self-reported populations of origin is essentially perfect.”

And Emil Kirkegaard wrote:

“In conclusion, social race and genetic ancestry are nearly interchangeable.”

Perhaps the most important and challenging principle of race realism—certainly the most challenging to the ideal of colorblindness—is that races differ not just physically but also psychologically. That is, races have different mental traits and tendencies, the most important of which is cognitive ability. Or, as Charles Darwin put it:

“The races differ also in constitution…Their mental characteristics are likewise very distinct; chiefly as it would appear in their emotional, but partly in their intellectual, faculties.”

This is not the place to defend hereditarianism since the debate between those who think that race differences in intelligence and other mental traits are substantially genetically caused (hereditarianism) and those who think such differences are mostly or entirely environmentally caused (environmentalism) is as voluminous as it is contentious. But two points. First, whatever the etiology, racial differences in intelligence are large and undisputed in the relevant literature. And second, hereditarianism is not irresponsible speculation or an intellectual veneer for bigotry; rather, it is a strong theory supported by copious evidence and powerful arguments. Even if one rejects it, the view that it is odious nonsense is untenable.

Hughes contends that race is neither entirely natural nor entirely socially constructed. However, he also holds an antiquated, essentialist view of categories, in which “real” concepts carve reality at clearly defined and precise articulations. Since race is a fuzzy concept, Hughes rejects it, arguing that any line we would draw between one race and another is arbitrary. The End of Race Politics proceeds to ignore human diversity, offering a view of race that is functionally the same as social constructionism.

The fallacy is the demand for a world of discontinuity and essentialism. That world was obliterated by Darwinism, which teaches that life is a continuum, not a system of eternal and unchanging forms.

Race is as real as many other fuzzy concepts. It is a genre, not an essence. And it is informative because it captures patterned genetic and phenotypic diversity and it matches continental ancestry. Races are different in more than superficial ways. Most importantly, they differ in mental characteristics including cognitive ability. The case for colorblindness must, if it is to be persuasive, wrestle with this reality. And in my estimation, its defeat is inevitable. Race realism is the unstoppable wheel that crushes the dream of colorblindness.

IS COLORBLINDNESS MORALLY DESIRABLE?

Written in limpid prose for a popular audience, The End of Race Politics is breezy and enjoyable, but it is not analytically scrupulous. After finishing it, I’m still not entirely sure what colorblindness means, which is hardly a picayune complaint about book whose chief argument is that we should embrace colorblindness. (To be fair, colorblindness is certainly a fuzzy concept—and I do understand it well enough to discuss it.)

Hughes writes that:

“The colorblind principle…[is that] we should treat people without regard to race, both in our public policy and in our private lives.”

He helpfully clarifies that contrary to the popular saying colorblind people still see color—they just try to treat people “without regard to race.” But this raises many questions and concerns, some of which are amplified by apparent inconsistencies in the book. Is it a violation of colorblind principles to prefer romantic partners who are a specific race? Is it a violation of colorblind principles to prefer friends who are a specific race? Is it a violation of colorblind principles to avoid dangerous areas of cities that are predominantly black? Is it a violation of colorblind principles to prefer certain communities over others because of their racial composition? One might think the answer to all these questions is “yes,” but that is not obvious to me, and Hughes seems ambivalent himself, at one point praising racial diversity in the New York Police Department:

“…it’s a good thing that the NYPD is racially diverse because effective policing depends in part on the perception of the legitimacy of the police. A police force that consisted of all white men would not be perceived as legitimate by a population as racially diverse as New York.”

Perhaps this is just a contradiction in Hughes’s thinking. Or perhaps he has a more nuanced idea of colorblindness in mind, one which is consistent with concerns about race and representation. Whatever the case, it is difficult to reconcile Hughes’s claim that racial diversity in the NYPD is good with his claim that “we should treat people without regard to race.” The act of praising racial diversity requires treating people with regard to race. Moreover, it encourages institutions to focus on race, especially if racial diversity is impossible to obtain through meritocratic processes.

Hughes ultimately concedes this point, writing:

“We want police forces that maintain race-neutral standards of entry and are racially diverse. But insofar as there is an inherent trade-off between those two goals—and there very well could be in some cases—it could make sense to compromise on the former.”

But this is incongruent with much of his book, including a sentence from the preceding paragraph:

“We often hear slogans such as ‘diversity is our strength.’ As nice as these platitudes may sound, race is a meaningless trait that does not map neatly onto anything that we should care about.”

Contending that race is meaningless while lauding racial diversity is a bit like claiming that color is meaningless while celebrating a rainbow.

In the next section, I will question the empirical feasibility of colorblindness. But here, I suggest that the unresolved questions and contradictions of The End of Race Politics draw attention to the possibility that colorblindness is not an unalloyed moral good, even in principle. I do not deny, of course, that it is seductive and has captured the imagination of many conservatives (and liberals alike). But at least part of its seductiveness is its promise that if we just work hard enough, the problem of race will go away. And most people who have become enamored with the ideal of colorblindness have not carefully reflected upon its ramifications.

Consider this scenario. A black man is accused of murdering a white woman. He is arrested and put on trial. His jury consists of twelve white people and the judge presiding over his trial is also white. Is this fair?

If you are like me, you would answer no. People should not face juries composed entirely of members of another race just as they should not be policed by departments composed entirely of members of another race. But once one accepts this, as Hughes apparently does, then one accepts that race matters. Race is morally consequential. And the only debate is about the management of race consciousness.

Perhaps a defender of the colorblind ideology would answer that racial diversity is only necessary in a racist society, a society in which white people have too often denied justice to black people. As racism subsides and colorblind principles spread, the need for racial diversity will wither away.

This sounds suspiciously like another failed prophecy of a withering away, namely, the Marxist prophecy of the withering away of the state after the realization of socialism. We have no reason to believe that colorblindness is possible or that people will ever cease to care about racial representation. Instead, racial affinity and tribalism appear to be natural and ineradicable features of human nature. A transfiguration of man into a cosmopolitan creature without racial preferences is almost certainly not on the horizon.

If racial affinity and tribalism are natural and possibly permanent, colorblindness becomes less appealing since it would require the constant suppression of an innate propensity, one whose fulfillment often provides a sense of meaning and identity. Consider a different example, one that is admittedly more extreme but not without real-world advocates: the abolition of the family. Suppose that I wrote a book espousing the principle of family blindness which forwarded the radical claim that people should treat others without regard to familial relationship both in public and in private. One would likely respond that such a principle is not only empirically implausible but also morally abhorrent. We should care more about our family than about strangers. (Some utilitarians, Marxists, and anarchists might reject this, but most people would not.)

But what makes race so different from family? Why should we eliminate private racial preferences but not familial preferences? I can think of two responses. First, racial affinity is almost certainly less strong than the affinity for immediate family. Therefore, it is easier to eradicate or at least to attenuate. And second, familial favoritism has not caused the tumult and tragedy that racial favoritism has caused. After all, the love for one’s own family has not inspired an eloquent but embittered dictator to attempt to annihilate all other families. And therefore, it is less objectionable.

The first response is at least partially correct. Racial affinity is less intense than familial affinity. In fact, racial preference is likely a weakened form of familial preference and depends on the same mental mechanisms which ultimately evolved through kin selection. However, it does not follow that we can eliminate or even subdue racial affinity. Nor does it follow that we should.

The second response is almost certainly false. Familial favoritism has produced vast grief and suffering, motivating internecine conflicts, ruinous wars, and perpetual competition. Its intensity and apparent intransigence to “reason” is precisely why radicals have often targeted the family, seeking to dissolve bonds of kinship so that more “rational” bonds could replace them. True, no Hitler of the family, fulminating against people with different surnames, rose to prominence in the twentieth century, but powerful people have killed from time immemorial to advance the interests of their family.

What distinguishes family abolition from colorblindness is that familial preferences are so strong that few people except for blinkered ideologues have truly believed that families could be abolished. Most politicians and intellectuals have accepted that families are natural and ineluctable units of human association, units that could only be abolished by tyranny and with a severe loss of meaning and significance. Therefore, healthy societies celebrate the unique love of families while curbing dysfunctional kin favoritism. They establish norms and rules that promote meritocracy, and they condemn nepotism, but they do not condemn the familial preferences that lead to it.

This might suggest a moral lesson for race. Perhaps colorblindness is not only impossible but also undesirable. After all, many people find meaning and identity in race just as they find it in family and community. Current orthodoxy (both left and right) ridicules this particular pursuit of meaning and identity only in whites, while praising and encouraging it in other races. Which is both a vexing hypocrisy and perhaps a confession that racial identity is appealing and meaningful. (To Hughes’s credit, he ridicules it in all races.)

Hughes writes:

“In envisioning a future for America, I imagine a country where citizens live securely and exercise their freedom to seek happiness…

In my ideal future, the people of this country would be so busy pursuing the things that really matter that we might go weeks or months at a time without ever thinking about the concept of race.”

But the reader is never told what the things that matter are nor why they cannot include ethnic or racial identity. Presumably, Hughes believes that family matters. And community. But why are these tribal units more legitimate sources of meaning than race? Furthermore, one might ask, if one’s happiness lies in cultivating racial identity, then is it not an encroachment on his or her “freedom to seek happiness” to discourage and stigmatize such an identity?

Of course, racial identity like other forms of identity (e.g., religious, political, et cetera) can lead to disastrous zero-sum competition which splinters social groups and reduces trust and community spirit. But it does not have to. Many believers embrace their religious identities and take pride in being members of a particular faith. They choose friends with similar religious beliefs. And they attend meetings that encourage and inculcate their identity. Yet, they do not want to wage war on other religious groups or even on heretics or apostates. Perhaps they would prefer to live in a community with other members of their faith. And perhaps they would fight for their religious interests in the political arena. But their identity is not a source of existential danger to the United States.

There is no obvious reason racial identity would lead inexorably to disaster, to fractious communities and polarized politics, while other such identities would not. In fact, honesty about racial consciousness, if judicious, might be liberating to the political system.

Colorblindness has been espoused so often and so enthusiastically by conservatives (and classical liberals) that it has become a platitude, one that is often endorsed without reflection. This is perhaps especially so because progressives hypocritically castigate whites for any display of racial identity, and white conservatives, already terrified of being called racists, are therefore wary of explicitly supporting white identity. In fact, most of them seem sincerely to wish that the race problem would just disappear. Colorblindness appeals to them for the same reason that quack medicine appeals to a person dying from an incurable disease. Desperation.

However, the moral case for colorblindness is not obvious; in fact, in some contexts, colorblindness seems actively immoral. Few people would like to face a jury of their “peers” composed entirely of members of another race. Even Hughes concedes that race does in fact matter in certain contexts in the very book that champions colorblindness! Once one accepts that racial representation is meaningful, the case for colorblindness starts to unravel. Racial consciousness is inevitable and possibly legitimate. And perhaps instead of espousing colorblindness, we should discuss responsible ways to guide racial identity. Especially since colorblindness is all but impossible to achieve in the real world. The wheel of race realism approaches.

IS COLORBLINDNESS POSSIBLE?

I have written this review as though The End of Race Politics chiefly criticizes conservative race realists while promoting colorblindness as an alternative to white identity. But that is not true. In fact, most of Hughes’s disagreement with modern identity politics is directed at what he calls the “neoracism” of progressives, which he deplores. And his attacks on this racial progressivism are often compelling and effective, as when he sharply but correctly notes:

“According to the strange dictates of neoracism, whiteness is inherently evil and blackness is inherently good.”

However, like many mainstream conservatives, Hughes mythologizes the civil rights movement, contending that its greatest leaders, especially Martin Luther King Jr., were advocates of colorblindness whose “deepest convictions” have been betrayed by modern progressives. In this telling, the optimism and universalism of the civil rights movement, a proudly colorblind movement, was hijacked by race hucksters and identity-obsessed intellectuals, who:

“…reject the explicit principles of civil rights leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.”

I do not pretend to be a scholar of the civil rights movement; however, I have some knowledge of the teachings and beliefs of its most prominent figures—and nearly all of them supported at least one species of explicit race preferences: affirmative action. This is hardly trifling since affirmative action is as close to a literally racist policy as one can encounter in modern America, and thus it flagrantly violates the principles of colorblindness. Debates abound, of course, about the nature of this support for affirmative action. Was it support for a minimalist form of affirmative action that assiduously searched for and recruited minorities from impoverished areas? Or was it support for a maximalist form of affirmative action that endorsed racial quotas?

I do not have the space or the knowledge to contribute intelligently to these debates. However, Hughes’s account appears unreliable. For just one example, Hughes uses the Philadelphia Plan, a quota-based affirmative action policy that required contractors to hire minority workers, as an example of a betrayal of the colorblind goals of the civil rights movement and asserts that:

“Clarence Mitchell, the pro-colorblindness chief lobbyist of the NAACP, called Nixon’s Philadelphia Plan a ‘calculated attempt…to break up the coalition between negroes and labor unions.’”

But this is misleading in two ways. First, the Philadelphia Plan was not created by Nixon ex nihilo in a startling betrayal of colorblindness. Rather, the Philadelphia Plan developed out of efforts in the Johnson administration that were supported by civil rights activists. As Dean Kotlowski wrote:

"The move toward affirmative action came instead from the Labor Department…Between 1965 and 1967…policy inched toward the forbidden terrain of racial quotas…Slowly, the agency adopted a result-oriented approach in which the government awarded contracts to companies that set targets for hiring minorities. In what became known as the Philadelphia Plan, LBJ’s Labor Department experimented with such numerical ‘timetables’ for construction contractors.”

What is more, Clarence Mitchell, although expressing concerns about Nixon’s motives, actually supported the Philadelphia Plan.

This debate might seem as tiresomely pedantic as a butterfly collector caviling about the misclassification of some species or another. But it is germane to the central thesis of this review that colorblindness is doomed to fail because it illustrates that the civil rights movement was inextricably associated with racial politics. Indeed, although the civil rights movement often used universalistic rhetoric to appeal to wide audiences, it was a racially conscious movement—one that sought to equalize the races in the real world. The problem is that this goal is impossible to achieve because the races are different in nontrivial ways. Colorblindness meets the crushing wheel of race realism.

Hughes argues that the rise of racial progressivism (i.e., “neoracism”) was caused primarily by (1) the loss of a common enemy (the Soviet Union); (2) the decline of Christianity; and (3) the invention and spread of smartphones and social media. These are plausible enough and have been forwarded elsewhere as causes of the rapid proliferation of racial progressivism, but, in my view, they ignore the chief cause: The failure of the civil rights movement to close large and persistent gaps between whites and blacks.

Those who held equalitarian views in the 60s legitimately believed racial equality was natural and that racial disparities were caused not by innate differences but by racist policies and a legacy of racial oppression. Repeal the policies and rectify the injustices, equality would inevitably follow. In that optimistic view, black underperformance was like a beach ball held beneath the water by the hand of racial bigotry; once the hand released the ball, it would naturally rise to the surface. But this did not happen. And that encouraged advocacy of more race-based policies, i.e., affirmative action, and the search for the elusive causes of the persistent gaps, since, by faith, equalitarians could not and would not accept that they were caused by innate race differences in cognitive ability and self-control.

Even a charitable observer might contend that although the civil rights movement began with noble intentions, it was transformed by the ruthless realities of race differences into an unscrupulous advocacy movement for black interests that has succeeded in appropriating vast resources from more successful races. This appropriation requires justification. If advocates of black (and now Hispanic) interests contended that they wanted to secure as many resources as possible from whites and Asians, most people would see their desire as morally illegitimate. They would be little better than self-interested opportunists waving the banner of racial identity. So they have created elaborate myths and theorized about subtle sociological forces such as systemic racism, the phlogiston of race disparities, which invariably vanishes when scrutinized but which yet must exist, permeating every pore of society.

Hughes offers a devastating critique of this lamentable degeneration of the civil rights movement into modern racial progressivism, an ideology which relies upon myriad fallacies, including, most importantly, the disparity fallacy, or the belief that “…racial disparities provide direct evidence of systemic racism.”

Although authors such as Ibram X. Kendi have occasionally been mocked for explicitly endorsing a version of the disparity fallacy, it is pervasive not only among progressives, but also among centrists and even some conservatives. Mainstream outlets across the spectrum are replete with articles railing against some supposedly racist outrage or another, citing large disparities between blacks and whites as evidence. Blacks are incarcerated more than whites. Racism. Blacks are expelled more than whites. Racism. Whites earn more than blacks. Racism. Whites live longer than blacks. Racism. The pattern of the accusations is as predictable as the clicks of a metronome.

But the social world is full of disparities. Blacks, for example, dominate the National Basketball Association (NBA), composing roughly 70% of the players in the league. Very few anti-racists assail the NBA for its bigotry against whites. Nor do New York Times columnists write philippics against Adam Silver, the commissioner of the NBA, for presiding over such a racist institution. Instead, the NBA is fulsomely celebrated. This speaks to progressive double standards about race and representation, of course, but it also illustrates our intuitive understanding that many disparities are the natural result of impartial processes.

Hughes helpfully distinguishes between malignant and benign disparities:

“Malignant disparities are those caused by discrimination—or otherwise arrived at through unfair process. Benign disparities arise naturally because of culture and demographic differences between groups.”

And he notes that many of the disparities that progressives bewail are benign. They are not caused by racist whites, racist institutions, or some mysterious racist miasma that subtly holds blacks down. They are caused instead by different interests, cultural backgrounds, or age compositions.

Unfortunately, this is where Hughes’s refusal to accept race realism and his implicit alignment with social constructionism and its denial that races differ from each other in any but superficial ways most distorts his analysis. His category of benign disparities has only two causes, demographic (e.g., differences in age) and cultural. But surely another salient cause of race disparities, one that is vastly more important than either culture or demography, is the nature of race differences in mental characteristics, including intelligence, self-control, and aggression.

A reader of this review who rejects race realism might think: But race realism is a controversial hypothesis, so why should Hughes consider it in his book? I hope my arguments in the earlier section on race realism were persuasive, but even if they were not, race differences in intelligence and other mental characteristics are not, in fact, controversial among those familiar with the literature. The only controversy is about the causes.

Beginning with the widespread use of standardized intelligence tests during the early 1900s, researchers discovered large race differences in IQ—especially between blacks and whites. The size of this gap has fluctuated a bit across time, and some scholars have argued that it shrunk substantially across the twentieth century, but the totality of the evidence suggests that it is still roughly one-standard deviation, i.e., blacks score roughly 85 (perhaps a bit lower) and whites score 100. (This is in the United States—though similar differences are found around the globe.) This difference is quite large and socially consequential. Incontrovertibly, it accounts at least partially for racial disparities in income, wealth, representation in STEM fields, grade point averages, standardized test scores, law degrees, medical degrees, and graduation rates (among other things).

Race differences in self-control are less well studied than intelligence; however, some studies have found lower levels of self-control in blacks, matching theoretical predictions based on differences in criminal offending. Race differences in violent crime are substantial, especially in large cities, likely reflecting both cultural and innate psychological differences—e.g., those in intelligence, impulsivity, and aggression. The exact mix of causes is impossible to say, but these patterns of disparate criminal offending are reasonably consistent across space and time in the United States.

Hughes’s optimism about colorblindness is directly related to (1) his misdiagnosis of the rise of racial progressivism and (2) his rejection of race realism (and concomitant silence about race differences). Once one accepts the reality of race differences, though, one sees that the civil rights movement was doomed to fail in its goal to equalize the races. And thus its transformation into racial progressivism, though perhaps lamentable, is understandable.

Real colorblindness would have to accept the existence of enormous outcome disparities in income, wealth, incarceration, et cetera, in perpetuity. In other words, it would have to accept that in virtually every desirable domain of social outcome, whites would outperform blacks (and Hispanics).

How big would these disparities be? We cannot know. But we can use data to speculate. For example, using the 2023 SAT Suite of Assessments Annual Report, one can examine SAT performance by race (though this is limited to proportions per units of score, e.g., the percentage of whites who scored between 1400-1600). The percentages are rounded, so the following are only estimates; nevertheless, they clearly illustrate the immense problem colorblindness faces. In 2023, the proportion of blacks in a pool of all the 1400-1600 test scorers was roughly 2% (n = 2,260), whereas the proportion of whites was 43% (n = 45,158) and the proportion of Asians was 46% (n = 48,527). On the other hand, the proportion of blacks in the pool of the 400-790 test scores was 27% (n = 67,786), whereas the proportion of whites was 24% (60,211) and the proportion of Asians was 2% (5,823). The overall group means on the test were blacks = 908; whites = 1082; and Asian = 1219.2

Thus, an entirely meritocratic university that accepted only students who scored 1400 and above would have few black people. (Unless, of course, it was such a desirable university that it could take all the high-scoring blacks.) And the numbers are even starker in the realm of elites scores, i.e., 1500s and above. In 2020, for example, Charles Murray estimated that the numbers were 900 blacks, 27,500 whites, and 20,000 Asians. Racial diversity at prestigious universities is not difficult to achieve, but it is not the kind of diversity elites celebrate, since it consists of whites and Asians, not blacks.

The disparities in SAT (and other standardized test) scores are caused primarily by differences in intelligence. And thus, they are unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

These differences have important downstream consequences. High status jobs are often cognitively demanding. And there are simply vastly more whites and Asians who can perform well in those jobs than there are blacks and Hispanics. Not incidentally, what evidence we have suggests that affirmative action does not stop at universities—it permeates society. Charles Murray’s analyses from the 1972 cohort of the National Longitudinal Study and the 1979 and 1997 cohorts of the National Longitude Study of Youth found large and consistent race differences in IQ among accountants, K-12 teachers, registered nurses, et cetera. The pattern was always the same. Whites scored the highest; blacks, the lowest (Hispanics were in the middle; Asians weren’t included). Furthermore, available evidence indicates that blacks score lower than whites on both subject and objective measures of job performance, which is consistent with the IQ disparities since IQ is positively related to job performance.

Even with massive affirmative action preferences and strong evidence of favoritism for blacks in hiring, progressives berate the United States for being racist against blacks. If race-based policies ended tomorrow, black-white disparities would swell like turbulent waves through which it is unlikely the fragile vessel of our multi-racial democracy could survive.

Blacks, told endlessly by elites that they have been victimized and oppressed by whites, would be understandably indignant about their diminished status. White progressives, dedicated to equalitarianism, a faith beyond reason, would advocate for riots that would dwarf the 2020 BLM riots. And intellectuals would write learned diatribes against whiteness, calling for an immediate end to the white supremacist West. Colorblindness would destroy the country. That is, unless we were honest about underlying race differences, which would require talking about and caring about race. Colorblindness contains its own contradiction and bursts apart from the inside once it confronts reality.

Hughes does not directly address this challenge. But he does offer some half-hearted bromides about replacing affirmative action with early interventions and “programs that close the skills gap.” For example, he writes:

“Efforts to achieve true equity should focus instead on high-quality kindergarten and pre-K, high-quality weekend learning programs, high-quality charter schools, and high-quality after-school tutoring. By ‘high-quality’ I mean programs, schools, and tutoring that focus on skills development.”

I do not know what “true equity” means—perhaps it means actual equality—but these recommendations remind me of the optimistic writings of many a 1970s Marxist who eagerly anticipated the creation of a revolutionary New Man who would no longer be selfish or materialistic. The problem in the case of closing skills gaps through early intervention is the same as it is in the case of eradicating selfishness: all efforts to achieve the desired goal have failed and will continue to fail.

As early as 1969, Arthur Jensen argued compellingly that compensatory education had failed to achieve its goal of closing skills gaps (i.e., intelligence gaps). Though many have attempted to refute his arguments, they hold up remarkably well. As Charles Murray wrote in Facing Reality:

“The short story is that ordinary exposure to education does indeed have an effect on cognitive ability for all children, but that no one has yet found a way to increase cognitive ability permanently over and above the effects of routine education. The success stories consist of modest effects on tests that fade out…

The NAEP results give us a simpler way to think about the intractability of the problem. The mean differences separating European teenagers from African teenagers in math and reading haven’t diminished since the last half of the 1980s. That’s more than three decades during which hundreds of billions of dollars have been poured into attempts to improve the education of disadvantaged children, including the intense effort to reduce test-score differences through No Child Left Behind.”

The notion that if we just try harder, strive better, and invest more, we will finally equalize the races is the same kind of quixotic notion conservatives correctly ridicule when progressives forward it. It is magical thinking. But it is understandable as a vain attempt to preserve colorblindness while rejecting race realism. Affirmative action is off the table since it focuses explicitly on race. What is left? Either accepting defeat or offering the same chimerical solutions that have been forwarded and tried thousands of times before. The wheel of race realism crushes colorblindness.

Worse, the faux colorblindness that is practiced in the real world serves as a weapon to bludgeon whites who collectively fight against the appropriation of their resources and the demographic transformation of the West. Elites do not denigrate racial identity for blacks or Hispanics. Quite the opposite. They encourage it. However, the moment whites express identity or racial consciousness, elites rail against it, warning that it presages the second coming of the great beast of white supremacy. Thus, white identity is taboo while black identity is celebrated. I commend Hughes for resisting this double standard. But his laudable consistency will be no match for the hypocrisy of those who will use his arguments to maintain the current status quo of double standards.

THE GOD THAT FAILED

The End of Race Politics is an optimistic book. It tells centrists, conservatives, and classical liberals what they want to hear. Race is an arbitrary social category. The real racists are not mainstream conservatives, but race-obsessed progressives who fixate on identity. If we reject their divisive worldview and embrace colorblindness, the problem of race will wither away. And thus, though constantly besieged by neoracists on the Left and benighted populists on the Right, the cosmopolitan dream of a flourishing multi-racial country is still possible.

Certainly, Hughes should be commended for his repudiation of progressive double standards about racial identity. And for ridiculing much of the balderdash that prevails in mainstream commentary on race. However, The End of Race Politics is a flawed book which embraces a dubious ideology. It relies upon specious arguments to reject a caricatured version of race realism. And once it rejects race realism, it effectively ignores human variation. Therefore, it does not address the most serious challenge to colorblindness: the existence of recalcitrant race differences.

It was this reality—race differences—and not some tragic strategical mistake that likely led to the development of racial progressivism. Early advocates of civil rights were mostly sincere equalitarians. They believed that racial equality was natural and that racial inequality was unnatural. Once anti-black racism was conquered, they argued, race gaps would close. But this did not happen. Therefore, disappointed equalitarians had to search for explanations. Systemic racism and other more subtle forms of prejudice were great candidates. After all, how else can we explain the persistence of race disparities? Thus, racial progressivism was the nearly inevitable development of the clash between equalitarianism and reality.

Colorblindness is not possible in a world in which race differences are large and reliably related to social disparities. If Hughes’s colorblind preferences prevailed, disparities would dramatically expand. And the billions of dollars that currently flow into the coffers of diversity bureaucracies and other projects specifically designed to elevate the status of blacks and Hispanics would stop. The reaction to this would be hysterical and destabilizing. Elites would become even more hostile to the country, decrying its relentless anti-black racism and fomenting revolution.

The only way to prevent such hysteria would be to discuss race differences openly and honestly. In other words, colorblindness is only possible if we talk about and focus on race. In other words, colorblindness is impossible.

1. Colorblindness is possible only if we talk about race differences.

2. Talking about race differences is not colorblindness.3: Therefore colorblindness is impossible.

At times, Hughes dimly recognizes this. Although he endorses colorblindness, he also explicitly endorses the value of racial diversity in certain institutions, e.g., the police department. This concession to race consciousness is a Pandora’s box for colorblindness. Once one accepts that race consciousness matters in some domains, it becomes difficult to deny that it should in others. And soon, the ideal of colorblindness becomes the reality of racial politics.

Like other seductive ideologies, colorblindness offers hope. But it does so at the expense of reality. Pluck out the eye of reason and you will see the promised land. These are precisely the most dangerous ideologies. Conservatives once understood this. And to their lasting credit, they fought valiantly against the false god of communism. Sadly, they have succumbed to the seductions of a different false god. Arthur Koestler wrote that “a faith is not acquired by reasoning.” Similarly, a faith is not lost by reasoning. It is lost when its preservation in the face of an implacably hostile reality becomes more trouble than it is worth. I hope this review adds to that trouble.

Bo Winegard is the Executive Editor of Aporia.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

I must emphasize that despite my strong disagreements with the book, it is admirably free of cheap shots or unsavory accusations. I wish more authors wrote with the charm of Coleman Hughes.

These should be treated as very rough estimates. I left out the category “Two or More Races” from the analysis. The resulting percentages with when that category is included are black = 2%; white = 40%; and Asian = 43%. For the 400-790 category, the respective percentages are black = 26%; white = 24%; and Asian = 2%. What is more, some test takers did not indicate race. I do not know if this group was random or not.

I think the most insightful part of the article is your diagnosis for the etiology of the pernicious narrative of systemic racism. After the civil rights movement, people who championed the equality of blacks and whites were soon bludgeoned by the cold, harsh reality of race disparities, thus inducing them to seek a false cause behind this unseemly disparity.

I have not read Hughes' book, but you seem to fundamentally misunderstand what the concept of color-blindness is. It has nothing to do with whether race is socially constructed or biological. Nor does it mean that no one can talk about race.

I think it can best be summarized as:

"Treat people as individuals, not as members of a group"

I know that people with red hair and people with black hair have their hair color determined by genetics. That does not mean that I treat them differently because of the color of their hair.

As an aside, I really do not like the term “color-blindness.” I prefer the term “merit-based decision-making by institutions.” If it leads to disparities so be it. Everyone benefits in the long run, even those who appear to be the losers.