Nassim Taleb is still wrong about IQ

Blocking your opponents isn't the route to knowledge.

Written by Noah Carl.

Back in 2019, Nassim Taleb posted a diatribe against intelligence research titled ‘IQ is largely a pseudoscientific swindle’. He has since updated the piece a number of times, inserting new paragraphs and screenshots to produce what can only be described as an aesthetic mess. Less important than the aesthetics, however, is the science — which Taleb gets badly wrong.

The central argument in the original version was that IQ “mostly measures extreme unintelligence”. Yet zero supporting evidence was provided. A few cherry-picked datapoints were added to subsequent versions, such as a table showing that the death rate from motor vehicle accidents in Australia flattens out above an IQ of 100. (Taleb wants you to take his word for it that what’s true of motor vehicle accidents in Australia is true in general.) However, it continued to rely heavily on simulations and theoretical points.

As evidence that the piece really was a diatribe, rather than a good-faith critique, Taleb referred to “racists/eugenists, people bent on showing some populations have inferior mental abilities”. He also casually smeared Charles Murray as a “mountebank”. Ironically, just a few months earlier, Taleb had published an article on “bigoteering”, which he defined as a “shoddy manipulation” to force your opponent to spend time explaining why they’re not a bigot. So Taleb says “X is bad” and then a few months later does X himself.

‘IQ is largely a pseudoscientific swindle’ has already been the subject of several rebuttals, including a particularly thorough one by Sean Last. However, I’d like to revisit the article — for two reasons. First, a number of relevant studies have been published since it was originally posted. And second, the damned thing keeps going viral on social media, most recently thanks to a fawning thread by self-proclaimed “statistics person” Kareem Carr.1

Taleb’s flawed “analysis”

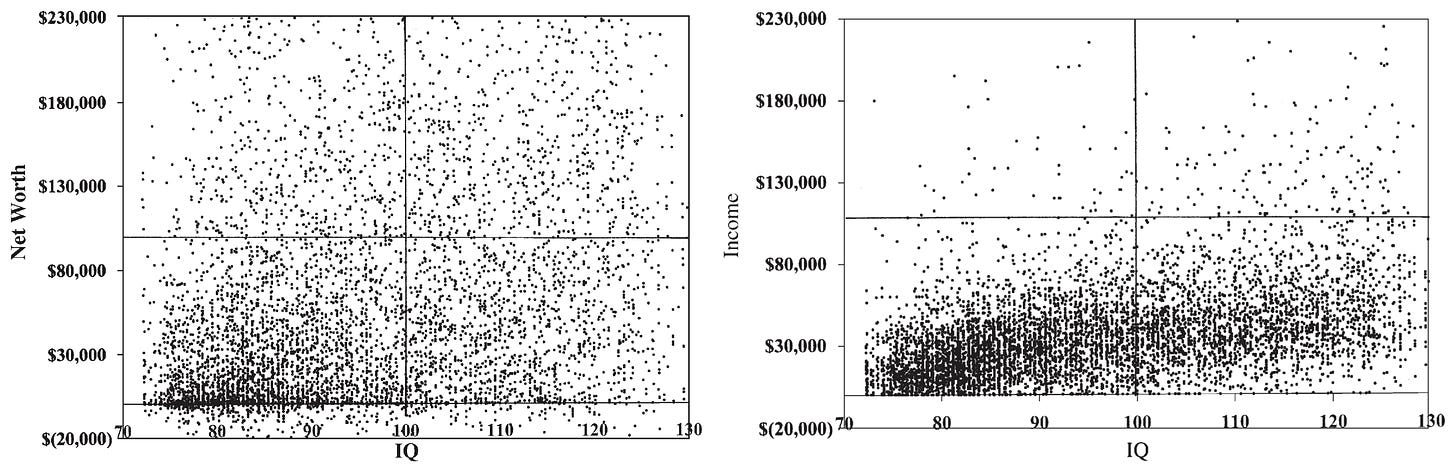

Before getting to the empirical evidence that refutes Taleb’s argument, it’s worth dealing with his flawed “analysis”. All versions of his article since March 2019 have included two charts taken from a 2007 paper by Jay Zagorsky. These charts plot IQ’s relationships with wealth and income in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth — the same survey used by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray in The Bell Curve.

In both cases, Taleb simply draws a horizontal line at $40,000 and notes that above the line there isn’t much of a relationship — there is “mostly noise”. Needless to say, I’m not impressed.

First, this will be true on a great many scatterplots, even when the correlation itself is quite strong. For example, if you simulate a correlation of 0.5 with, say, 500 datapoints and then cover the bottom half of the chart, it will be hard to discern much of a relationship in the top half. This doesn’t mean the relationship isn’t there.

Second, Taleb’s claim is that IQ “mostly measures extreme unintelligence”, and to test that you would examine the relationship above a certain value of IQ, not above a certain value of wealth or income. In other words, it’s the right-hand side of the chart he should be looking at, not the top half. Jonatan Pallesen bothered to test whether the relationship flattens out, rather than relying on Taleb’s path-breaking method of eyeballing the chart. Comparing the linear and locally weighted regression lines, he found no evidence that it does.

Third, while the association between IQ and wealth is admittedly rather weak2, the association between IQ and income is clearly visible on the chart. And it would be even more visible if the income variable had been log-transformed, as it arguably should have been. Income is known to have a positively skewed distribution, so it is typically “logged” prior to analysis.

Threshold effects?

As mentioned above, Taleb’s central argument is that IQ “mostly measures extreme unintelligence”. Fortunately, this is readily testable. And we’ve already seen that it is false in one of the few datasets Taleb actually cites in his article. Americans of high intelligence earn more, on average, than those of merely average intelligence.

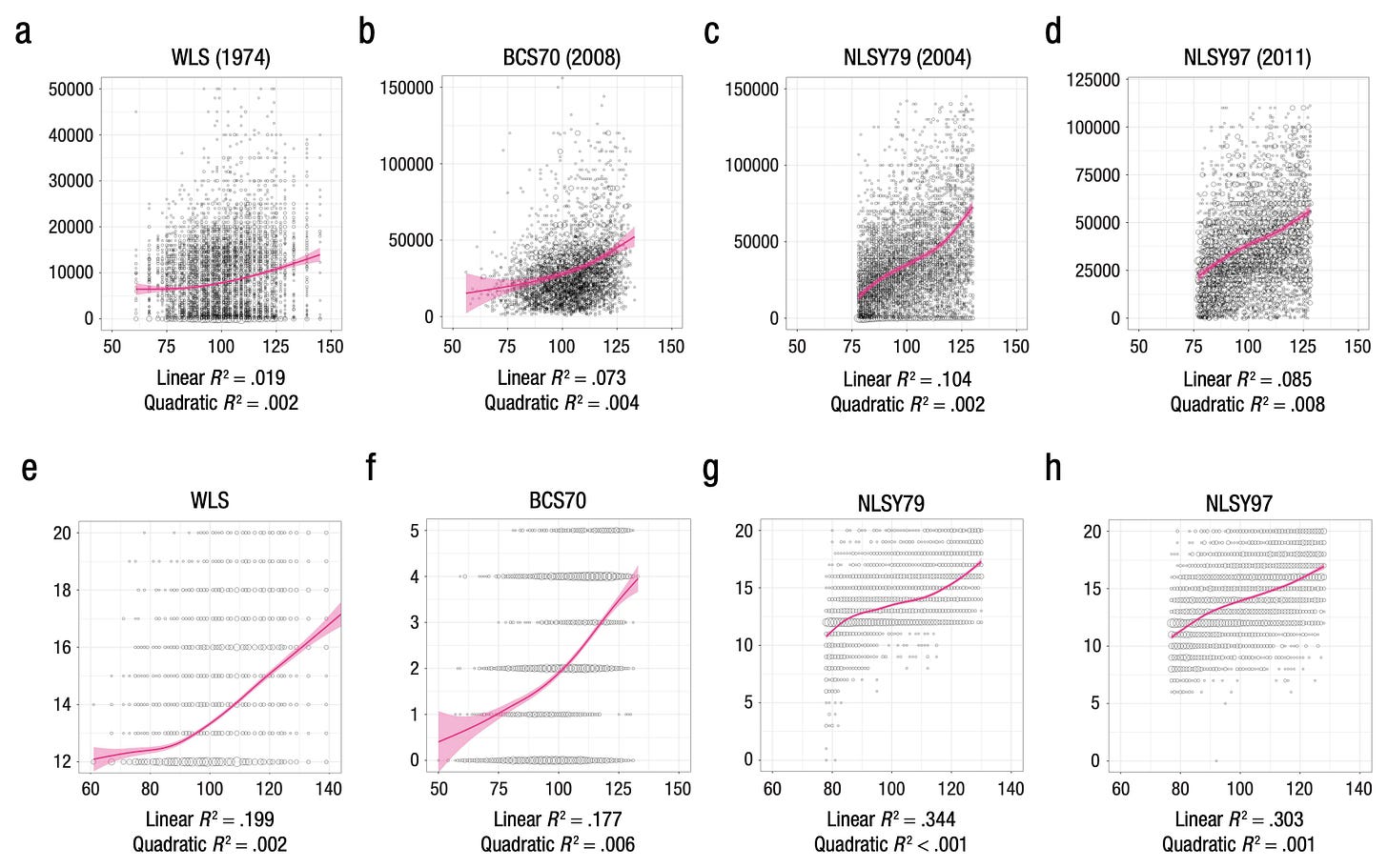

Two recent studies have tested Taleb’s claim more rigorously. Matt Brown and colleagues examined the relationship between cognitive ability and various outcome measures in four longitudinal datasets. They tested for non-linearity (i.e., flattening out) in several different ways but found “no support for any downside to higher ability and no evidence for a threshold beyond which greater scores cease to be beneficial”. As you can see in the charts below, none of the lines becomes shallower and several of them become steeper.

A similar study was carried out by Spencer Greenberg and colleagues, based on data from an online testing service. It again found that “effects were similar across the whole range of IQ scores”.3

Taleb has actually addressed the paper by Brown and colleagues in the latest versions of his article. His characteristically humble response is that his argument is now “closed” because the paper “confirmed all of its conclusions”, proving that “IQ explains almost nothing”. As evidence for this, Taleb presents a table showing the percentage of the variance in each outcome measures above and below certain IQ thresholds that is not explained by IQ, with the values ranging from 83% to 100%.

The first thing to say is that this is called moving the goalposts. Brown and colleagues clearly refuted Taleb’s claim that IQ “mostly measures extreme unintelligence”. Hence he is falling back on a different claim — that IQ doesn’t explain enough of the variance to personally satisfy him.

Indeed, his table is somewhat misleading because the values correspond to subsamples of the data defined by IQ thresholds. The overall percentages of variance explained by IQ are about twice as large as his table implies (see Figure 6 here). For example, his table implies that IQ explains 7% of the variance below an IQ of 100 and 12% above. Yet Brown and colleagues found that it explains about 26% of the variance overall.

What’s more, Brown and colleagues may have underestimated the strength of the associations between cognitive ability and some of the outcome variables. Income is notoriously difficult to measure accurately, which has the effect of reducing correlations with predictor variables.

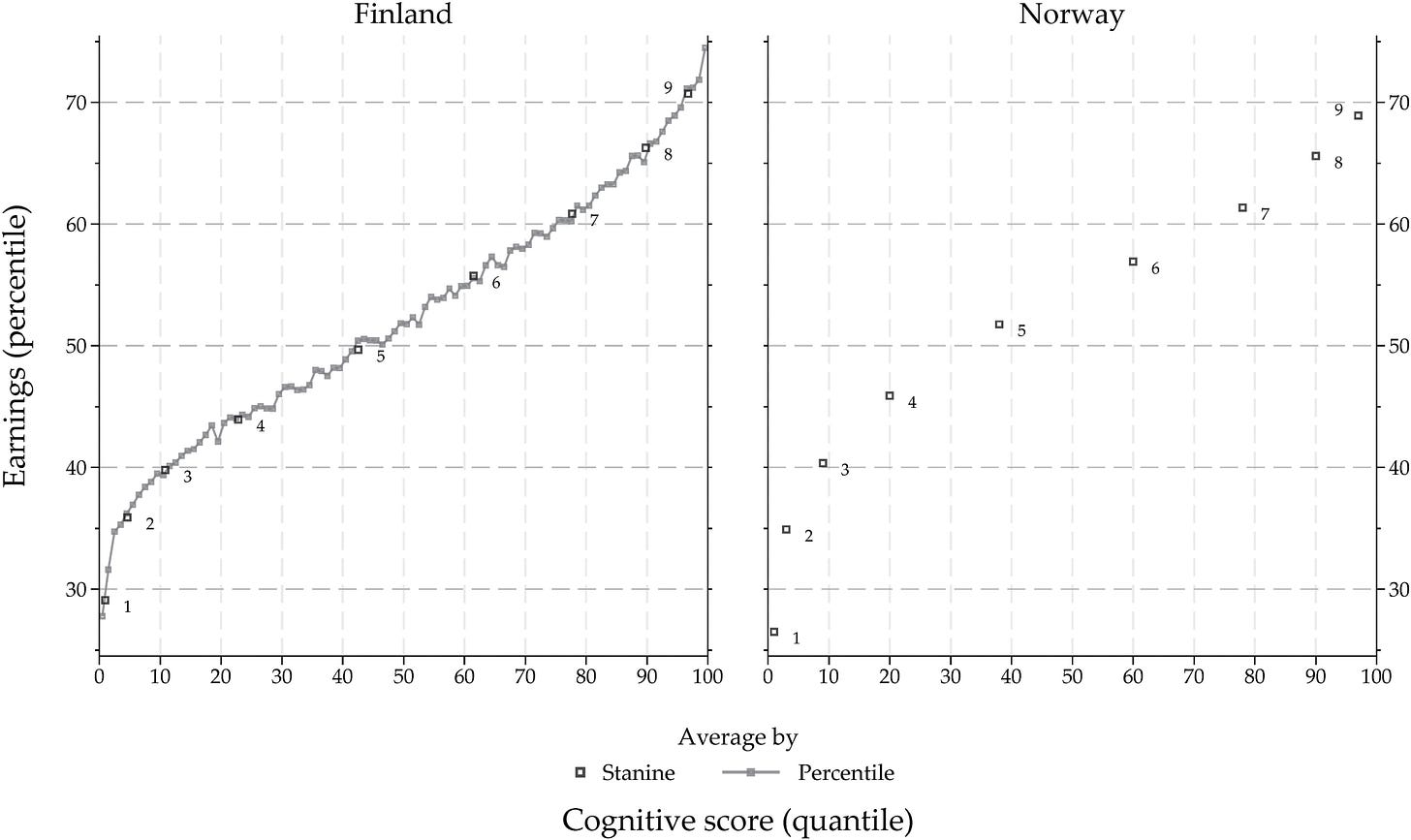

Further evidence that IQ remains predictive in the upper half of the distribution can be found in two recent Nordic studies. Marc Keuschnigg and colleagues examined cognitive ability’s relationships with wages and occupational prestige in Sweden. They ended up “rejecting the claim that past a certain threshold having even higher cognitive ability does not matter”. Bernt Bratsberg and colleagues performed a similar analysis for Norway and Finland, reaching the same conclusion.

Scientific accomplishment

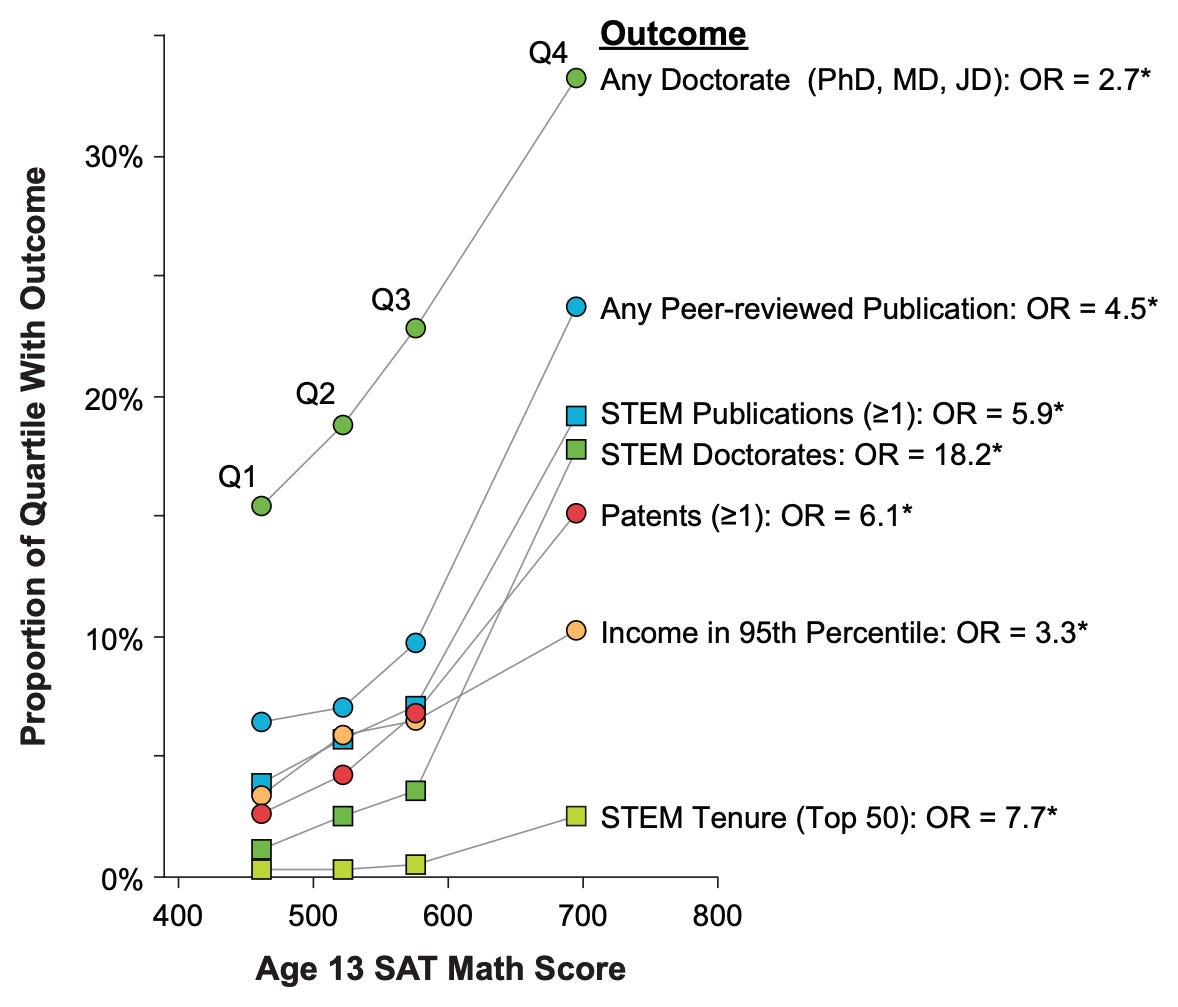

Long before Taleb ever dreamed up ‘IQ is largely a pseudoscientific swindle’, there was overwhelming evidence against his central argument. I’m referring to the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth, which has followed cohorts of Americans who scored in the top 1% of the Math SAT at age 13. As Kimberly Robertson and colleagues stated back in 2010, “empirical research fails to substantiate the threshold hypothesis”.

In the chart below, participants from the Study are divided into quartiles based on their age-13 Math SAT score. Hence Q4 corresponds to the top 25% of the top 1%, while Q1 corresponds to the bottom 25% of the top 1%. Even within this highly selected sample, cognitive ability has predictive validity. Participants in Q4 were more likely to obtain a doctorate, file patents and publish scientific papers. They were also more likely to have an income at the 95th percentile.

When it comes to scientific accomplishment, we have to turn Taleb’s thesis on its head: IQ mostly measures extreme intelligence.4 Having an IQ of 90, as opposed to an IQ of 70, isn’t much of an advantage in science since you have to have an IQ of at least 110 to contribute anything at all. And most top scientists are in the 120+ range. So rather than there being a threshold above which IQ doesn’t make much difference, there’s a threshold below which it doesn’t make any difference.

This is consistent with smart fraction theory, which holds that practically all technical innovation is done by people in the right tail of IQ — the population’s “smart fraction”. The theory is strongly supported.

Conclusion

While Taleb has made important contributions in a number of areas, such as the study of rare events, his commentary on intelligence falls well short of the mark. He makes no effort to seriously engage with the literature and repeats claims that were debunked years ago. He also debases himself by making the sort of absurd allegations you’d expect to hear from a woke student activist, such as “the online magazine Quillette seems to be a cover for a sinister eugenics program” (yes, he literally says that).

Crucially, his assertion that IQ “mostly measures extreme unintelligence” is flat-out wrong (no pun intended). For outcomes like income and educational attainment, IQ remains predictive well into the upper half of the distribution. And when it comes to scientific accomplishment, it’s far more predictive in the right-hand tail than in the left.

Taleb pours scorn on “IYIs (intellectuals yet idiots)”, apparently unaware that intelligence research is largely rejected by the academic establishment. Ironically, it’s his position that screams IYI.

Noah Carl is an Editor of Aporia.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

Wealth is an unwieldy variable for several reasons. It depends heavily on random factors, such as the timing of bequests from deceased relatives. Well-off people can have low or even negative wealth if they hold a lot of debt (e.g., student loans or a mortgage). And it’s much harder for individuals to estimate their wealth than their income.

A caveat is that relationships were very weak, suggesting that the measure of intelligence may have suffered from ceiling effects and the sample may have been non-representative.

Unfortunately this is all too believable. Taleb’s covid hysteria was off the charts. Apparently he’d dismissed all the epidemiology that showed its seriousness was limited to those already vulnerable, such as the elderly. Instead he bought into the fear. It’s always disappointing when smart people don’t use their heads.

I covered the entirety of Taleb’s article as a five-year anniversary: https://hereticalinsights.substack.com/p/iq-and-talebs-wild-ride