Written by Noah Carl.

In 1931, a large group of German scholars published a book titled A Hundred Authors Against Einstein, criticising the theory of relativity.1 This was an early example of academics getting together and leveraging sheer numbers to try to discredit a colleague’s work.2 Einstein, for his part, was unfazed. Commenting on the book, he’s reported to have said, “Were I wrong, one professor would have been quite enough.”

In recent decades, efforts of this kind have become more common. Yours truly was the subject of an academic petition back in 2018.3 But many others have also been targeted. The petitions — or “open letters” as they are sometimes termed — can be quite funny to read. So before getting to the point of this article, let’s go over three of my favourites.

In 2017, the historian Rachel Fulton Brown became the subject of an open letter addressed to her department at the University of Chicago. It was prompted by some slightly profane comments she’d made about a fellow historian, as well as her associations with — gasp — Jordan Peterson and Milo Yiannopoulos. The letter condemned Brown’s “ignorance of basic theoretical principles of race theory” and her “fundamental lack of knowledge concerning the discourses of structural racism and white supremacy”. It also claimed that her words do “grievous damage”. Grievous, I tell you!

That same year, the philosopher Rebecca Tuvel became the subject of an open letter addressed to the journal Hypatia, which had recently published her article In Defense of Transracialism. The petitioners alleged a “failure of the peer review process, and one that painfully reflects a lack of engagement beyond white and cisgender privilege”. Hilariously, they had to add a postscript following a backlash because their original letter had not explicitly denounced “anti-Blackness”. The petitioners thanked the instigators of this backlash for pointing out the “dangerous erasure of anti-Blackness and the erasure of the Black labor on which the rhetoric of our own letter is built”. You can’t make this stuff up.

In 2018, the physicist Alessandro Strumia became the subject of a petition denouncing a recent talk he had given at CERN, in which he argued that male not female physicists are discriminated against in hiring and promotion.4 The petitioners began by engaging in the ridiculous hyperbole that “the humanity of any person … is not up for debate”. They also accused Strumia of having a “deep contempt for more than half of humanity”. Incredibly, the petition was signed by over 4,000 people, including many respected physicists (i.e., people you might have hoped would be less susceptible to such obvious hysteria). And as if the whole thing couldn’t get any more cringe, it was posted under the name “Particles for Justice”.

Which brings me to my point. Since 2019, I have been collecting academic petitions and open letters, and have assembled a database of no less than 81. My database only includes petitions targeting other scholars: I was not interested in those supporting certain policies (e.g., the minimum wage) or calling attention to broader issues (e.g., climate change).

To qualify for inclusion, a document had to condemn or harshly criticise a specific scholar or call for sanctions against them (e.g., disinvite them from giving a talk, retract their paper) and be signed by at least five academics. Criticisms published in academic journals were excluded, as were petitions signed exclusively by students and departmental “statements” that lacked a list of signatories. I was interested in efforts by groups of academics to damage another scholar’s reputation by appealing to the authority of their names and credentials.

The list of targets is available here. Do let me know if you’re aware of any that I’ve missed (I am still refining the database). A special mention goes to Bruce Gilley, who has been the subject of four separate petitions — more than anyone else.

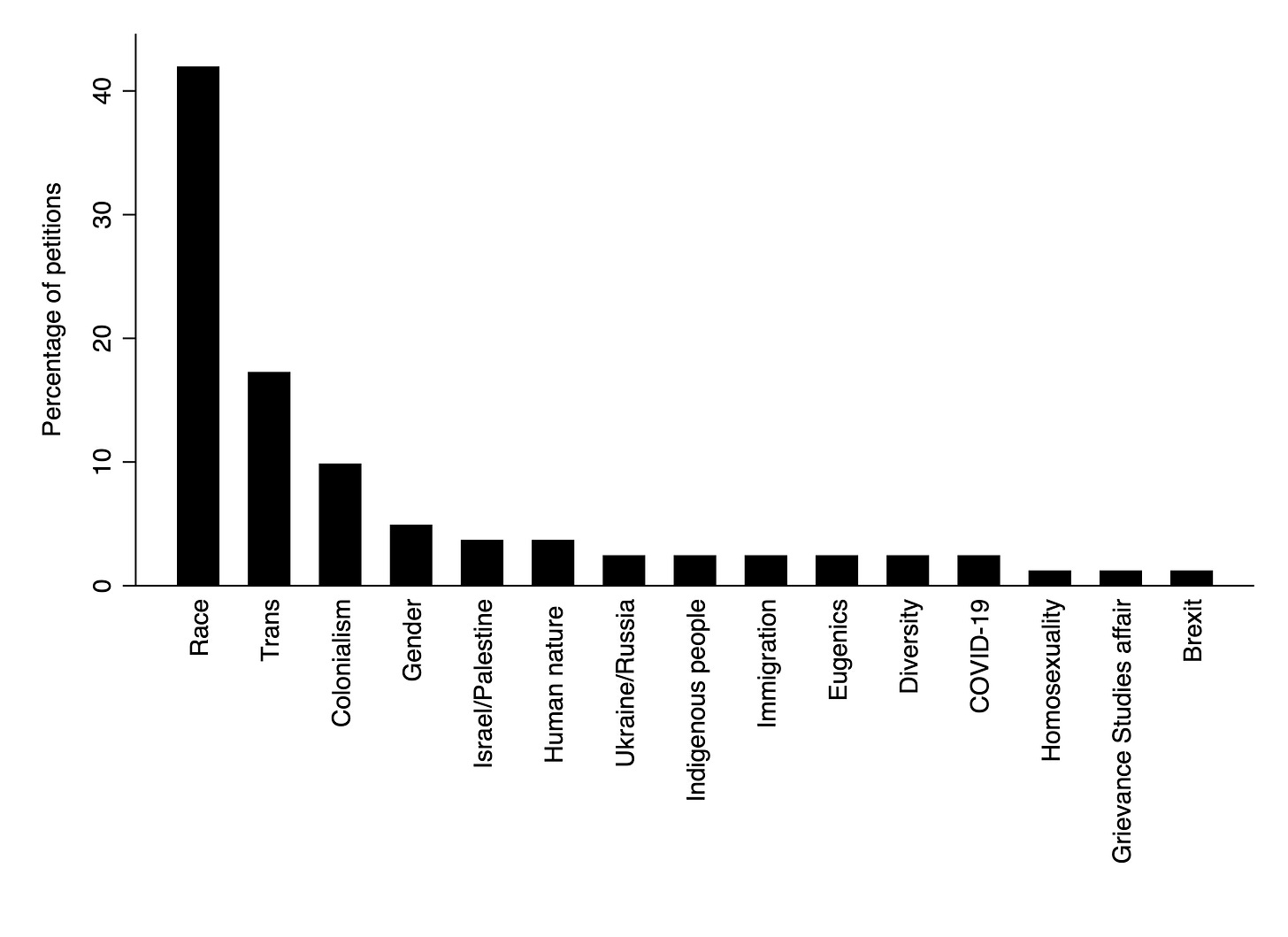

The number of signatories per petition ranged from 5 to >11,000, with a median of 300.5 In terms of issues, race was the most common one by far, accounting for 42% of all petitions.6 Trans was the next most common, accounting for 17%, followed by colonialism.

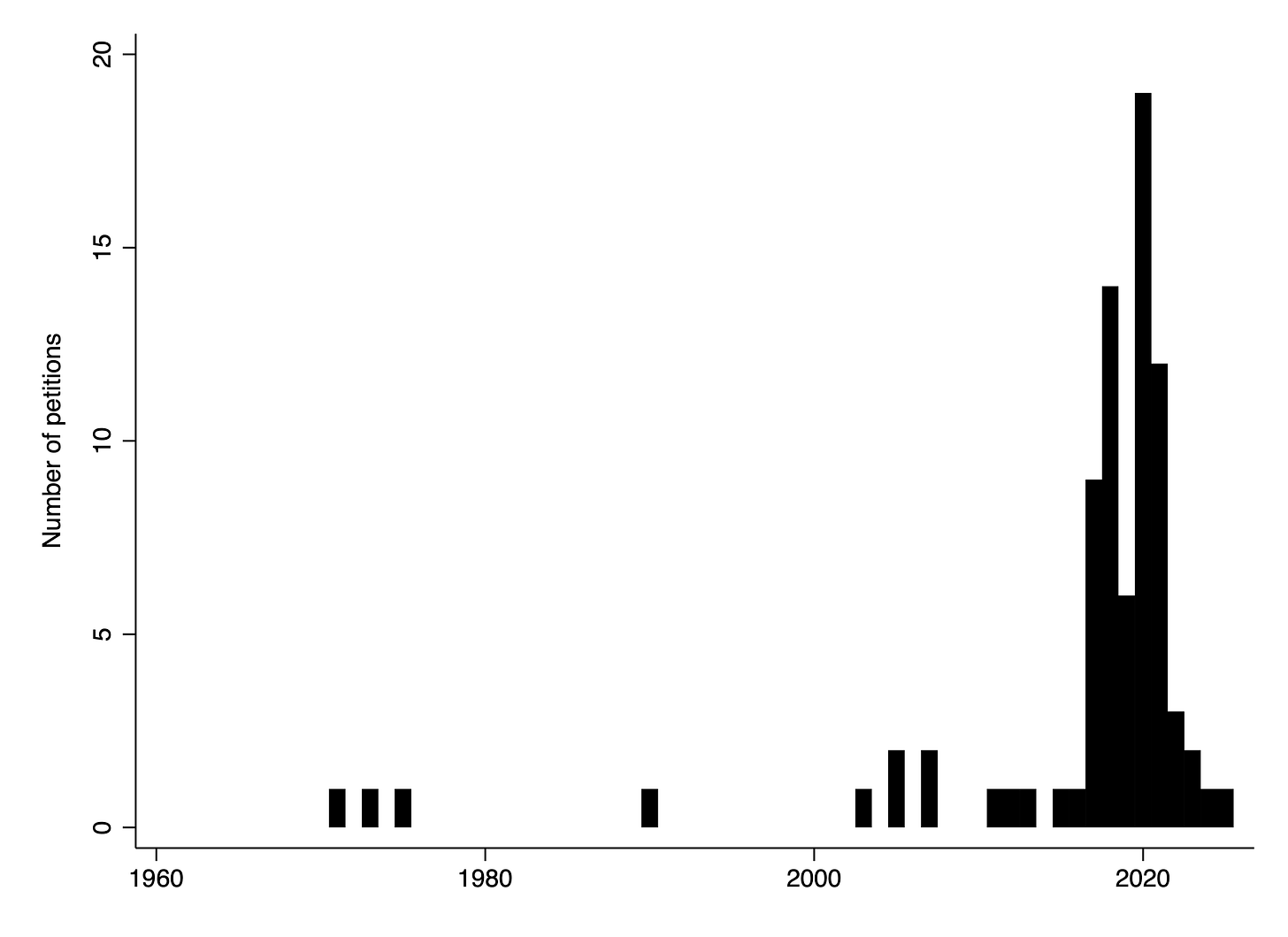

In terms of the distribution over time, the petitions were overwhelmingly concentrated at the peak of the Great Awokening, with 60 out of 81 occurring in the period 2017–2021. The two earliest petitions correspond to those against the hereditarian researchers Richard Herrnstein, Arthur Jensen, Hans Eysenck and William Shockley. The third, in 1973, is the letter criticising E. O. Wilson’s book Sociobiology. The fourth, in 1990, is a petition against the hereditarian researcher Michael Levin.

Of course, the concentration of petitions in the most recent period could be partly an artefact of those in earlier periods being harder to find and document. On the other hand, petitions signed by academics (as opposed to students) were undoubtedly rarer in the past, so you might expect that each one would leave a larger impact on the historical record. To track down cases, I used a combination of search engines and AI. I also emailed other targets to ask if they were aware of any cases I had missed.

Reading through the petitions, I noticed that the same words and phrases appeared again and again. Hence I coded each petition for the presence of six themes, based on the presence of specific terms.7

43% mentioned terms related to “diversity, inclusion and equity”. 70% mentioned terms denoting “isms” or “phobias” (e.g., “racist”, “transphobic”). Half mentioned the term “community” (e.g., “transgender community”). 51% mentioned terms relating to harm (e.g., “harmful speech”). Half mentioned the term “marginalized” or its synonyms (e.g., “oppressed”). And 35% mentioned the term “legitmize” or its synonyms (e.g., “normalize”).

In fact, the basic structure of many of the petitions was almost identical: emphasise the importance of DEI; identify the target as a racist/transphobe; claim that the target’s speech is harmful to marginalised communities; assert that any association with the target legitimises racism/transphobia; and call for sanctions against the target.

It’s important to remember that academic petitions and open letters comprise only a subset of (actual or attempted) academic cancellations. Indeed, the vast majority of such cancellations are instigated not by academics but by irate students, administrators, alumni, donors, politicians and members of the public. FIRE’s Scholars Under Fire Database lists 1,662 incidents and for only 7% is the “source” given as “scholars”.

Nonetheless, academic petitions are of interest due to the blatant flouting of scholarly norms they represent. I’m referring to such norms as, you know, addressing the argument not the person, and communicating through scholarly channels rather than using mob tactics to pressure institutions. When it comes to students, a certain amount of activism is to be expected. But academics are supposed to be serious people. At the very least, they’re meant to act like adults. Can you imagine, say, 300 electricians ganging up on a colleague because he expressed a view they didn’t like? It would never happen.

Another reason academic petitions are of interest is that they comprehensively debunk the myth that most academics are independent minded truth-seekers who think for themselves. Compared to the general population, your typical academic is probably less intellectually courageous, and more susceptible to groupthink, social contagion and herd behaviour. Even scientists working in the most arcane areas of physics are not exempt from this generalisation.8

While academic petitions are not a new phenomenon, they appear to have been extremely rare until around 2017, when they suddenly exploded in frequency. Their trajectory therefore mirrors that of various other phenomena from the Great Awokening, such as cancellations in general and use of terms like “racism” and “transphobia” in the news media. Three issues — race, trans and colonialism — account for about two thirds of all petitions. The first two are unsurprising given their prominence in public discourse at the time; the latter is there due to its prominence in left-wing academia.

As for the decline over the last four years, I would chalk it up to the general retreat of wokeness, as well as the fact that many of the most “troublesome” individuals have already been cancelled.

Noah Carl is an Editor of Aporia.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

The authors are often described as “Nazi professors”, but only a handful were anti-Semitic and several were Jewish (one of the lead authors was called Hans Israel). Nor is the book anti-Semitic.

Of course, there were earlier examples of scholars attempting to discredit their colleagues’ work, often on grounds of “heresy”.

This spurred me to produce a satirical guide for how to write an academic petition.

Some of the signatories may not have been academics, especially on the larger petitions. For eight petitions, the number of signatories was unknown.

This is consistent with my and Michael Woodley’s finding that racial or population differences in intelligence is the most common topic for controversies in the field of intelligence research.

Seven petitions whose texts could not be tracked down were excluded from this analysis.

Recall the petition against Alessandro Strumia. There have also been several petitions signed by geneticists and several signed by economists.

Outstanding, Noah. I'd be interested in the study for Econ Journal Watch — you could riff at Aporia as well, of course.

I think of the following quote from Edgar Allen Poe:

"The 'thousand profound scholars' may have failed, first, because they were scholars, secondly, because they were profound, and thirdly, because they were a thousand."

This is great. Did you also compile the names of all the signatories? The next step is to examine the demographics of the signatories. I bet Orwell will be proven right (young women).