Robert K. Merton and the Modern Ethos of Science

The problem isn’t just a few rabble-rousers who managed to infiltrate science from the “studies” departments.

Written by Noah Carl.

In his pioneering work The Sociology of Science, Robert K. Merton defined the “ethos of science” as that “affectively toned complex of values and norms which is held to be binding on the man of science”. Although the ethos had never been formally codified, he argued it could be inferred from the “moral consensus of scientists” as expressed in “countless writings on the spirit of science” and “indignation directed toward contraventions of the ethos”.

As to the specific norms Merton was referring to, he outlined four – which have since become known as the Mertonian norms of ideal scientific practice.

The first is universalism: scientists and their claims should be judged on the basis of impersonal criteria. The second is communism: scientific discoveries are a product of collaboration and are owned by the whole community. The third is disinterestedness: science is done for the sake of advancing knowledge, not for some other reason. And the fourth is organised scepticism: scientific claims must be tested and verified before they can be accepted.

Merton’s book was published in 1973 – more than half a century ago. What is the status of Mertonian norms today? Adherence is not what it could be, to put it mildly. Scientists become the targets of vicious cancellation campaigns if they step out of line on hot-button issues. They must voice support for inane left-wing tropes like “diversity” that have been shoehorned into academia by activists. And they’re told that basic concepts like objectivity are manifestations of a nefarious ideology called “whiteness”.

The problem isn’t just a few rabble-rousers who managed to infiltrate science from the “studies” departments. Major institutions like journals and professional associations have become mouthpieces for left-wing ideology – frequently spouting the sort of verbiage you’d expect to hear at the DSA Convention. Of course, some disciplines are more politicised than others, with social science and medicine faring worse than biology, chemistry and physics.

One area that has a long and storied history of politicisation is the genetic basis of human intelligence, especially group differences. As I proceed to argue, all four Mertonian norms have been largely abandoned by the scholars and other gatekeepers working in this area.

Universalism

The acceptance or rejection of scientific claims, Merton wrote, “is not to depend on the personal or social attributes of their protagonist”. So you can’t dismiss a theory because you don’t like the person advancing it. Nor should you prevent that person from taking part in research. “To restrict scientific careers on grounds other than lack of competence,” Merton notes, “is to prejudice the furtherance of knowledge”. Indeed, “free access to scientific pursuits is a functional imperative”.

What do we find today when it comes to the study of genes and intelligence?Anyone accused of promoting “racism”, “white supremacy” or “eugenics” – often for no other reason than that they subscribe to a particular explanation for intractable group differences – is essentially unwelcome in academia. Their claims are rejected and their careers are restricted because of irrelevant, personal criteria.

If you are deemed a “racist”, you cannot get an academic job, and if you have one you’ll most likely lose it. You’ll be disinvited from conferences after your presentations have already been accepted. You’ll be completely ostracised by the laboratory you directed for 35 years, even if you won a Nobel prize for discovering the structure of DNA. And your papers will be posthumously retracted – on explicitly moralistic grounds.1

Communism

“Property rights in science are whittled down to a bare minimum,” Merton wrote. “The scientist’s claim to “his” intellectual “property” is limited to that of recognition and esteem”. In addition, “the institutional conception of science as part of the public domain is linked with the imperative for communication of findings. Secrecy is the antithesis of this norm”. So scientists must be transparent; they must make their results available to others, and must share their data with them.

What do we find today when it comes the study of genes and intelligence? Access to important datasets is increasingly restricted. Often only people with the requisite credentials and institutional affiliations may use them. And even then, researchers must promise not to ask “forbidden” questions.

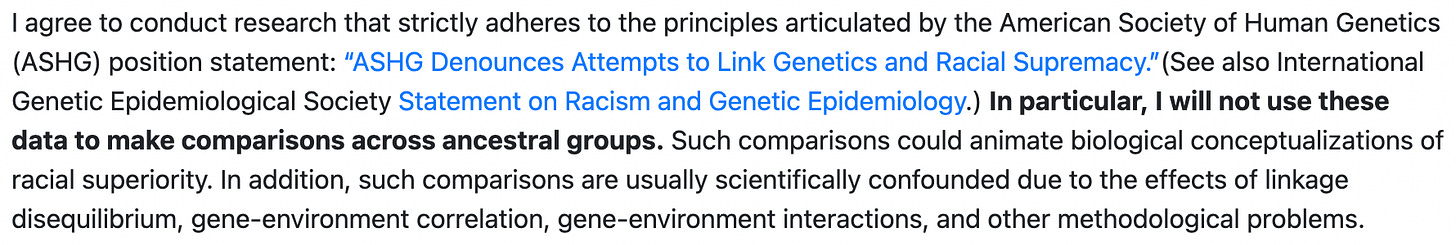

Back in 2021, the Social Science Genetics Association Consortium (a group of researchers supposedly interested in the genetic basis of human behaviour) included the following stipulation among the terms of use for their data:

So you had to agree not to perform particular analyses that might be of scientific interest – in part because doing so could “animate biological conceptualizations of racial superiority”. To the SSGAC’s credit, it seems that this stipulation was subsequently watered down; the boldface sentence and the one after it have been removed. You now merely have to read a position statement dealing with “racial supremacy”.

However, not all data-holders have backtracked like the SSGAC did. James Lee, a distinguished researcher at the University of Minnesota, has described his travails attempting to access the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes – held by the publicly funded National Institutes of Health. Sometimes, he notes, the NIH denies access to variables like IQ on the grounds that studying their genetic basis could be “stigmatising”. And in certain cases, the organisation has “retroactively withdrawn access for research it had previously approved.”

Intelligence researcher Stuart Ritchie had a similar experience with the NIH. He and his colleagues wanted to compare the accuracy of various polygenic predictors of IQ. Yet when attempting to access summary statistics from a 2019 study, they were told that such data “should not be used for research into the genetics of intelligence” or certain other social outcomes.

One important dataset held by the NIH is All of Us, which aims to collect genetic and health information on a racially diverse sample of 1 million Americans. All of Us has a specifically tailored policy on “stigmatising research” whose definition of “stigma” comprises five elements:

The policy states that the curators “should take steps in earnest to prevent resource use with the potential to stigmatize and to punish bad actors”. What does this mean in practice? Science was told that All of Us “would likely reject any proposals focused solely on educational attainment”. (The Million Veteran Program, another major biobank, said the same thing.) Indeed, Charles Murray spoke off the record to someone with access, and they outlined the limits researchers face, namely “no study of IQ” and “no topic that might show offensive group differences”.

Yet another researcher who has had trouble on this front is economist Greg Clark, as he explained in an interview with Aporia last year. When applying for funding for a project on genes and social mobility from the National Science Foundation, Clark encountered the view that “we should not spend any money on any research that would not allow us to increase rates of social mobility”.2

Disinterestedness

“Science,” Merton wrote, “includes disinterestedness as a basic institutional element.” He argued that widespread adherence to this norm, as reflected in the “virtual absence of fraud”, is attributable to a “distinctive pattern of institutional control” whereby scientists attempt to verify (or indeed falsify) one another’s claims. Thanks to this incentive structure, scientists generally work towards the common goal of advancing knowledge, rather than the personal goal of achieving status.

However, achieving status for oneself is not the only motive one might have for acting with partiality in the context of science. Another reason for doing so is pursuing some political objective, such as “anti-racism”. And when the balance of political forces becomes sufficiently skewed, as it has in social science, the incentive structure to which Merton referred breaks down. Which is why we find scientists openly privileging some hypotheses while disfavouring others.

There are many examples of political philosophers calling for restrictions on the study of group differences in IQ. (Michael Woodley and I discuss half a dozen in our recent paper.) But you’d imagine that scientists working in the relevant fields would want to follow the truth wherever it may lead. This turns out not to be the case, as a recent “consensus report” on social and behavioural genomics makes clear.

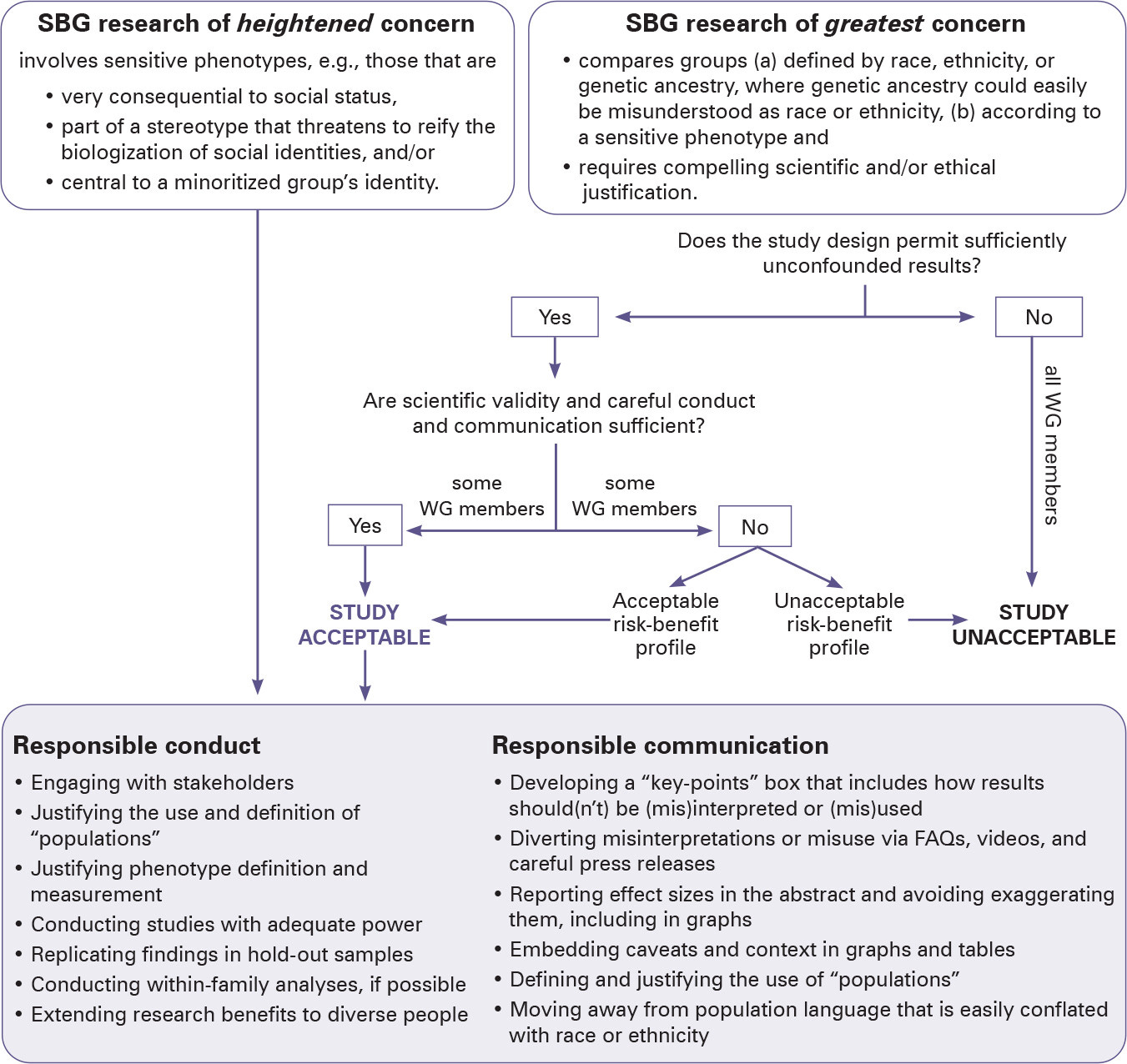

The report summarises three years worth of deliberations between nineteen scholars with supposedly “very diverse views”. These nineteen comprise bioethicists, historians, psychologists, economists and geneticists. After discussing the history of behavioural genetics and the science of polygenic prediction, they consider the risks and benefits of SBG research. Part 6, dealing with “justifiable and unjustifiable” research, is of most interest.

The authors distinguish between research of “heightened concern” and research of “greatest concern”. The former refers to research on “sensitive phenotypes” like intelligence, while the latter refers to research comparing racial or ancestry groups on such phenotypes. You’ll be pleased to learn that research of “heightened concern” is considered justifiable. And research of “greatest concern”? Here’s what the authors have to say: “We all hold that, absent a compelling justification – a criterion that some of us think will never be met – researchers should not conduct, funders should not fund, and journals should not publish such research.”

As to what they mean by “compelling justification”, they include the following schematic. It shows that all nineteen scholars – the ones with “very diverse views” – believe that research on group differences in IQ is “unacceptable” unless the study design permits “sufficiently unconfounded results”. It also shows that some of the nineteen believe that, even then, such research is “unacceptable” unless the study has a favourable “risk-benefit profile”.

Now, we’d always like our results to be less confounded. But I can’t imagine any criterion that would allow one to demarcate “sufficiently” unconfounded results from “insufficiently” unconfounded ones. Even RCTs are not definitive. Would Charles Darwin’s The Descent of Man qualify as “sufficiently” unconfounded? Presumably not. Which means that one of the seminal texts on human evolution would be deemed “unacceptable”.3

Note the asymmetry here. The authors do not call for restrictions on group differences research in general. They only call for restrictions on research into genes and group differences. (Studies on environmental causes of group differences are totally fine.) So you’re allowed to study some explanations for an observable phenomenon, but not allowed to study others. I’m unsure exactly what you call this, but it’s not science.4

Organised scepticism

Scientific practice, Merton wrote, involves “the temporary suspension of judgement and the detached scrutiny of beliefs”. Indeed, “the scientific investigator does not preserve the cleavage between the sacred and the profane.” As a consequence, science may “come into conflict” with attitudes that have been “crystallised and often ritualised in other institutions”. Which institutions? “Resistance on the part of organised religion has become less significant,” he notes, “as compared with that of economic and political groups”.

Scientists should remain detached from the subject matter of their research, and they should subject all relevant claims to critical scrutiny. Dogma has no place in science. In fact, for science to function properly, it must be kept separate from domains like politics that are not predicated on organised scepticism. Yet when it comes to the study of genes and intelligence, we find that fact-value conflation is widespread while contested propositions are treated as dogma.

Referring to the consensus that human populations are quite similar from a genetic point of view, the geneticist David Reich notes that “this consensus has morphed, seemingly without questioning, into an orthodoxy.” The orthodoxy maintains that “average genetic differences among people grouped according to today’s racial terms are so trivial when it comes to any meaningful biological traits” that they can be safely ignored. Yet as Reich points out, “it is simply no longer possible” to ignore such differences.

For example, a 2018 statement by the American Society for Human Genetics claims that “any attempt to use genetics to rank populations demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of genetics”. Which is an odd pronouncement coming from a professional association of scientists.

If they mean “rank according to some metaphysical notion of superiority”, then it would demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding – though not of genetics. Rather, it would demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of epistemology. Geneticists have not discovered that metaphysical superiority resides somewhere other than the genes. Metaphysical superiority is, by its nature, not amenable to scientific inquiry. Hence geneticists have no special expertise talking about it, and the statement above is arguably false.

On the other hand, if they mean “rank according to average genetic potential on some socially valued trait”, then the statement is clearly false. Ignore IQ for a second. Height is socially valued. Does the ASHG want to insist that using genetics to rank, say, Western Europeans and Congolese pygmies by average height would represent a “fundamental misunderstanding” of their discipline?

In 2020, the ASHG issued another statement to “reiterate our strong opposition to efforts that warp genetics knowledge for social or political ends”.5 Here we find a similarly dubious pronouncement: “it is inaccurate to claim genetics as the determinative factor in human strengths or outcomes when education, environment, wealth, and health care access are often more potent factors”.

To begin with, why is “environment” specified in addition to “education”, “wealth” and “health care access”? Aren’t those other three all part of the environment? More importantly, it is not inaccurate to claim genetics as the “determinative factor” in certain outcomes. What about Down’s Syndrome, or other conditions resulting from aneuploidy? What about pygmies’ short stature, the Bajau’s prowess in diving, or Tibetans’ resistance to altitude sickness?

The modern ethos of science

Half a century ago, the sociologist Robert Merton outlined four norms of ideal scientific practice: universalism, communism, disinterestedness and organised scepticism. These were the informal rules by which scientists were expected to conduct themselves. Today they are under threat. One area where they’ve been largely abandoned is the study of genes and human intelligence.

People with the “wrong” scientific or political views are unwelcome in academia (even if they discovered the structure of DNA). Publicly-funded datasets are increasingly off-limits, rather than being accessible to the whole scientific community. Researchers working in relevant fields openly privilege some hypotheses for non-scientific reasons. And professional associations issue forth vaguely-worded and dogmatic statements.

The modern “ethos of science” bears little resemblance to the one described by Merton. And if anything, it’s only getting worse.

Noah Carl is Editor at Aporia.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

When analysing data from the UK Biobank, geneticist Francisco Ceballos and his colleagues “discovered a population with 6k times more incest (father-daughter)” but the “bioethics committee did not allow us to publish” because “it could be used by far-right groups to attack this community”.

In spite of all this, the authors want you to know they are all “highly averse to the idea of policing the production of knowledge”.

Already in 2022, the journal Nature Human Behaviour had announced that they “reserve the right” to reject or retract articles that are “premised upon the assumption of inherent biological, social, or cultural superiority”.

The irony of saying this in what is obviously a progressive-coded statement was apparently lost on them.

I've been thinking lately about how social science has transformed the modern world. If you look into all the major social movements since the end of WW2, they all had some sort of backing by social science research - everything from the UNESCO Statement on Race to Brown vs. Board of Education, to open borders immigration. It now appears obvious that most of that research was of poor quality or outright fraudulent, and the the research that should have been completed was prohibited for ideological reasons.

There are a number of theories lately about the rise of "wokeness" and the root causes of our modern social milieu, but in almost every case it seems the the arguments for radical change were supported by bad science. I know many highly educated liberal-minded people and they commonly justify their beliefs with various social science dogma. They are technically making the best educated decision based on the scientific knowledge they are exposed to, it's just that the science is often of poor quality. The conservatives, with their instinctual mistrust of intellectuals, ended up being right on many issues simply because they didn't believe the experts.

Perhaps the replication crisis, our racial turmoil, mass migration and even the explosion of transgenderism in kids all have the same root cause - bad science.

In an earlier, pre-Woke world, the world's biggest genetics researcher, BGI, was collecting DNA samples from geniuses around the world. Many Google staff were invited to contribute, but the bulk of the samples came from China, where geniuses a plentiful. As I recall, the IQ division was run by a teenager, a fascinating story in itself.

Steve Hsu, who was involved with BGI knows the history, which would make a good Aporia feature.