Written by Noah Carl.

Many rightists concerned about mass immigration seem to be labouring under the delusion that the way to solve the issue is by getting “our guys” into power. Elect the right man – a Trump, a Farage, an Orbán – and things will start falling into place. If we could just piece together an electoral coalition broad enough to win 51% of the vote (or seats), then finally the matter could be dealt with. It should be obvious, however, that this view is completely naive and mistaken.

The problem is that in democracies, governments have a habit of changing hands. Even good ones get voted out. “Your guys” can do everything right and then get blamed for a financial crisis caused by entirely unforeseeable events on the other side of the world. Sooner or later, “the other guys” will be voted back in. And when they are, there’s nothing to stop them reversing everything “your guys” did. Asylum policies can be tweaked; settlement rules can be modified; even treaties can be re-signed. It only takes one election to be right back where you were before.

And that’s not the most pessimistic scenario. If the “other guy” happens to be an Angela Merkel, a Boris Johnson or a Justin Trudeau, you might find yourself in a much worse position than you were before.1 To paraphrase the IRA: restrictionists have to win every time; their opponents only have to win once. And winning every time just isn’t realistic.

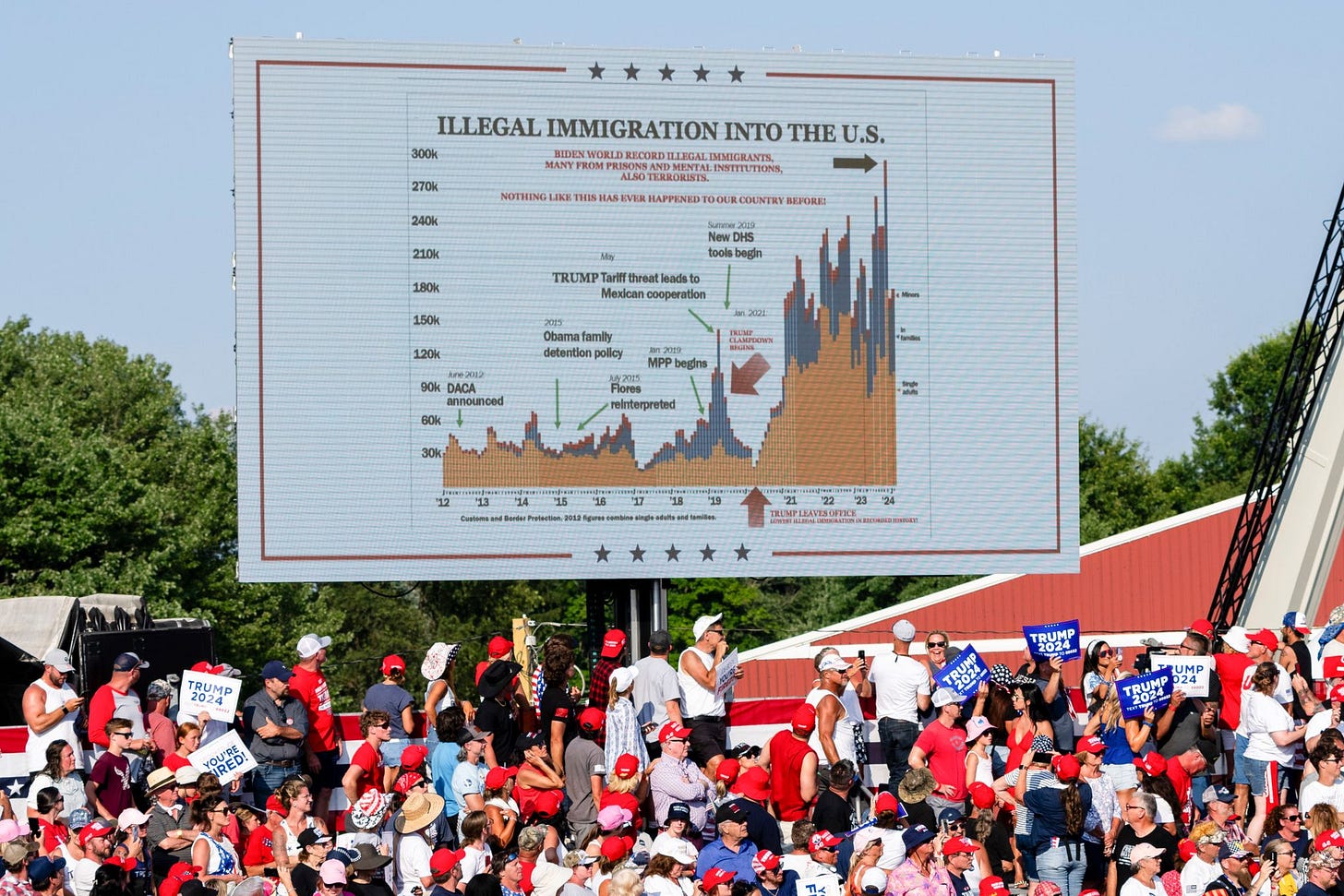

The problem I’m describing is clearly visible in the illegal immigration chart Trump credited with saving his life during the assassination attempt. It shows that border apprehensions reached a multi-year low in the final year of his presidency, but then skyrocketed soon after Biden took office.2 So any work Trump had done to reduce the level of illegal immigration was completely undone by his successor. Trump may well bring illegal immigration down if he’s re-elected president. But what’s to stop a future president Newsom, say, from letting it climb straight back up?

During the campaign to get Trump elected the first time, Michael Anton wrote an influential essay, ‘The Flight 93 Election’, in which he argued that conservatives were facing a situation analogous to that of the passengers who heroically stormed the cockpit of United Airlines Flight 93. “Charge the cockpit or you die,” Anton wrote. “You may die anyway … There are no guarantees. Except one: if you don’t try, death is certain.”

A major reason for Anton’s gloom about the prospect of a Clinton Presidency was, of course, her stance on mass immigration. And in the essay, he scoffs at those obtuse Republicans who insist that immigrants will soon reveal their “natural conservatism” at the ballot box by voting Republican rather than Democrat. Yet Clinton’s stance on mass immigration wasn’t very different from Biden’s. And mass immigration is arguably still the “mystic chord that unites America’s ruling and intellectual classes”, to use Anton’s words. Does this mean “death is certain” every time a Democrat wins the presidency?

It might have occurred to you that many policies can be reversed by the next government: tax rates can be cranked back up; utilities can be brought back into public ownership; patronage flows can be rerouted to favoured interest groups. What’s so special about immigration? What is it about that issue that makes focussing solely on electoral politics naive and, indeed, mistaken?

Demographics are destiny. Once a person has been admitted and granted permanent settlement, you’re basically stuck with them (and with their children, their grandchildren and so on).3 Which means that although specific immigration policies can be changed, the effects of those policies cannot. If every time “the other guys” get into power, they let in X million people and give them the right to stay, “your guys” will be fighting a losing battle. The ratchet of demographic change will move in only one direction, and the best you can hope for is to simply slow it down.

Suppose communists seize power and proceed to socialise the means of production. The economy will take a major hit, but it will eventually recover: China became one of the world’s fastest growing economies after Deng Xiaoping implemented his pro-market reforms. Demographic changes, on the other hand, are much harder to undo.

The ratchet effect of electoral politics, whereby “your guys” put the brakes on demographic change and then “the other guys” slam the accelerator, is particularly intractable for two reasons. First, “the other guys” (by which I mean left-wing parties) will always be tempted to “elect a new people” by bringing in migrants to bolster their electoral coalition. In both the US and the UK, ethnic minorities vote overwhelmingly for left-wing parties. At the last Presidential Election, only 26% of non-whites voted Republican. And at the last General Election, only 21% voted Conservative or Reform.

The second reason the ratchet effect is so intractable is that immigrants are more supportive of immigration than are natives.4 According to my calculations, the difference amounts to about 0.33sd in the UK and about 0.30sd in the US.5 Each new person therefore contributes to demographic change in two ways: first, through his addition to the population; and second, by boosting the level of pro-migration sentiment. It’s true that immigration often provokes a backlash, whereby natives become more hostile than they otherwise would have been. But this backlash may not be great enough to offset the impact of immigrants themselves.

Assuming (plausibly) that it’s not, demographic change may culminate in what could be termed an “immigration singularity”. This is the point where the process becomes self-sustaining because immigrants tend to support pro-migration parties, and once they reach a critical mass in the population, restrictionists can no longer win elections.

Don’t misunderstand me. I’m not saying that people opposed to mass migration shouldn’t bother voting or campaigning for their preferred candidates – that they should be indifferent between Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson, or Donald Trump and Gavin Newsom. My claim is: they have to recognise that getting the right man into office isn’t a long-term solution. Sure, it will slow the problem down and make it more manageable, like slapping duct tape over a burst pipe. But the duct tape isn’t going to last forever; at some point, the water needs to be turned off.

So what is the long-term solution? Curtis Yarvin would say an absolute monarch is the only institution capable of breaking up the pro-migration oligarchy and regaining control of our borders. While his arguments are often ingenious, I fear that his proposal has as much chance of being adopted as the Constitution Party has of making a clean sweep this November. If a second Stuart Restoration is what it takes to address the immigration issue, we’re going to be waiting an awfully long time.

The real solution is altogether less exciting: people opposed to mass migration need to win the argument. Restrictionism and demographic stability must triumph in the marketplace of ideas. Admitting hundreds of thousands of people from disparate cultures should become as unthinkable as persecuting minorities, dismantling the welfare state or starting a war with an ally. It should be off the table, politically. If the immigration statistics come in and show that city-sized numbers have been admitted, the Prime Minister should be expected to resign.

You might point out that there was a sizeable majority against immigration in Britain up until at least the 1990s, but this didn’t stop Tony Blair’s government throwing the doors open as a way to “rub the right’s nose in diversity”.6 However, having public opinion on your side (to the tune of 60 or 70% of the population) doesn’t equate to winning the argument. Why not? To prevail in the sense described in the previous paragraph, you need to win over elites. Or enough of the them, anyway: there will always be idealistic Guardian columnists who don’t believe in borders, just as there will always be business lobbyists whose salaries depend on them not understanding that migration has costs.

You need to win over enough judges, journalists, policy wonks, high-level bureaucrats, and indeed, politicians. There must be a general consensus on the issue. (You don’t have to persuade every last racial grievance activist in the decolonisation movement.) Supporting mass immigration should be seen as quirky and eccentric – like being an anarchist or an Austrian-school libertarian.

How do you go about achieving this? Narrative-friendly rhetoric. You have to recognise that liberals (of both the left and classical variety) subscribe to a different narrative than conservatives – that they have different values, and speak a different political language. Trying to convince them the way you would a conservative isn’t going to work.

As Arnold Kling observes, conservatives tend to frame issues in terms of civilisation versus barbarism, whereas left liberals tend to frame them in terms of oppression versus exploitation. Meanwhile, classical liberals tend to frame issues in terms of liberty versus coercion. Which means that pontificating on the greatness of Western civilisation and the barbarism of immigrants is a losing strategy. It might be a good way to rally fellow conservatives – but it’s unlikely to persuade anyone on the other side.

Liberals don’t want to hear about “the Great Replacement,” “Third World invaders” or “White genocide”. They see the circumstances of someone’s birth, such as whether they were born on this or that side of a national border, as largely accidental. They have a much wider circle of empathy than conservatives (which is part of the reason we ended up with mass immigration in the first place). And they really, really don’t want to be seen as racist.

However, this doesn’t mean they’re immune to argument. (You’d better hope they aren’t because otherwise the ratchet of demographic change is going to keep turning every time “your guys” lose an election). In my experience, the most effective approach is pointing out that the numbers don’t add up. What do I mean?

Despite being generally well-informed, many liberals think the current level of immigration is something given by nature – and you can either be a bad person who wants it to be lower, or a good person who wants it to stay the same. What they don’t realise is that we already exclude the vast majority of people who want to migrate. According to surveys conducted by Gallup, hundreds of millions of Africans, Asians and Latin Americans would like to come and live in the West; the main reason they haven’t shown up yet is they assume they’ll be turned away at the border. So if we adopted a different migration policy, such as “anyone who can make it to the West will be allowed in”, the level of immigration would be far, far higher.

What’s more, the number of people who want to migrate is only going to rise. The highest concentration of potential migrants is found in Sub-Saharan Africa – whose population the UN projects will exceed 2 billion by the middle of the century. Which means that in only 25 years, Sub-Saharan Africa will go from being 50% larger than Europe to almost three times larger. There will soon be billions of people who would like to come and live in the West.

Taking in billions of people is obviously not feasible, as even the most sanctimonious liberals would be forced to concede. If we did it, there would be some kind of societal breakdown. Or else the actual far-right would come to power and start deporting people en masse – which wouldn’t be a pretty sight. The plain fact is: we cannot help more than a small fraction of migrants who want our help. Any help we can provide is a drop in the bucket; for every person we pat ourselves on the back for letting in, we have to shut the door on nine others.

Once the liberal has conceded that excluding the vast majority of people who want to migrate is a matter of necessity, there is no longer any case for letting people in simply because they were born on the wrong side of a national border. Migration controls become legitimate. And this raises a question: “if we must exclude the vast majority of migrants anyway, why should we take the hundreds of thousands we’re currently taking?” Immigration demonstrably contributes to social tensions, including the rise of the “far right” (who ostensibly pose an existential threat to democracy). Why would we inflame social tensions, and risk having a “far right” government, just to provide a drop in the bucket’s worth of help to poor people overseas? After all, there are more effective ways to help such people than by taking a small fraction of them as immigrants.

At this point, the liberal may pivot from a humanitarian argument to one based on the need for talent and skills. But from the perspective of his own professed values, this argument is even less plausible. High-skilled emigration strips developing countries of their best and brightest citizens – of the human capital they desperately need to develop. So if you care about the welfare of people left behind in those countries (as liberals claim to), you really ought to oppose it. As Sir Paul Collier, author of The Bottom Billion, notes: “We might be feeding a vicious circle, in which home gets worse precisely because the fairy godmothers leave.”

My point in this essay is not to scold right-wing activists for posting edgy memes on Twitter, or tell them to cool it with the anti-immigrant remarks lest they offend liberal sensibilities. (I’m not trying to play the moralist.) Rather, the point is to emphasise that mass immigration can’t be curtailed for any meaningful length of time until a sufficient number of liberals have been brought on board. Which means that getting into power isn’t enough: winning the argument is necessary.

Noah Carl is Editor at Aporia.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

The decline during the final year of Trump’s presidency may have been partly or largely due to Covid.

In principle, people can be retroactively stripped of citizenship and deported – but it’s almost never done in practice. Nor should it.

Immigrants’ support for immigration is evident in the phenomenon of chain migration.

For the UK, I analysed data from Wave 23 of the British Election Study Internet Panel. Pro-migration sentiment was measured on an 11-point scale from “allow many fewer” to “allow many more”. Three different indicators for ‘immigrant’ were used: not being a British citizen; not being born in the UK; and having an ethnicity other than “white British”. Effects were similar across the three indicators (when controlling for age and sex). For the US, a similar analysis was done using the 2016 wave of the American National Election Study.

Win the argument rather than win the election. A very basic point but one that hadn't occurred to me.

And don't annoy liberals by listing all the ways migrants are destroying our way of life, as I usually do. Instead point out that those we do already let in are only the smallest tip of an iceberg, an iceberg capable of sinking our puny western lifeboat.

Okay, now I know how to argue nicely with annoying do-gooders. Now I just need to corner one for long enough to make that argument.

But a great essay.

You can't "win the argument" with liberals. If they were open to noticing-reality-type reasoned argument then they would not be liberals (of the kind I think you mean). Being a 21st c. 'liberal' is not, at bottom, about weighing the evidence on immigration or any other real issue....it's about imagining yourself more sophisticated than the commen herd. A form of personal vanity really....unfortunately a very seductive one. https://grahamcunningham.substack.com/p/the-migrants