Written by Bo Winegard.

Since at least the beginning of written history, people have understood that humans are a diverse species. Although some modern scholars contend that race is a relatively recent invention, the documentary record suggests that ancient Greeks and Egyptians recognized that human populations are different from each other in predictable and patterned ways. Natural philosophers have long wrestled with human diversity, trying to understand its causes, its organization, and its consequences.

During the Enlightenment, they elaborated and systematized once vague and inchoate ideas, giving birth to the modern concept of race. Since then, race has been a contentious idea, inspiring furious debate and morally charged dissent. Indeed, most modern intellectuals argue that race is unreal, a classificatory relic from a blinkered past that persists chiefly because it allows privileged groups to protect their unearned advantages. Race exists because racism exists.

Paradoxically, many of these same intellectuals argue that racially conscious policies and analysis are the only way to confront pervasive racial injustice. Race may be illusory, but it has bewitched so many people that breaking its spell requires promoting more racial awareness.

The view that race is a pernicious myth, that most ethnic inequalities are caused by racism, and that the way to combat racial injustice is to heighten racial consciousness is so widespread that it is now the orthodox position, and views which contradict it are often either objurgated or suppressed. They are rarely taken seriously or addressed charitably.

Although most people who accept this orthodox position have not considered its theoretical assumptions carefully, and some almost certainly profess allegiance to it merely to avoid social or professional sanction, it is a coherent world view, consisting, inter alia, of these propositions:

Race is a social construct. Although humans vary genetically, they do not vary in predictable, patterned ways that can be classified as races.

Human populations vary primarily only in superficial features, such as skin color, although they may vary in some underlying traits such as blood types or lactase persistence.

Human populations do not vary in psychological traits and tendencies that were shaped by natural, sexual, or social selection.

Human population disparities, which are large and numerous, are caused by pervasive racism.

The primary challenger to this modern orthodoxy is a (more sophisticated) version of the older view: race realism. Race realism contends that racial categories carve out real and conceptually interesting variation in the biological world. It therefore argues that race is not an illusion or a distortion of human diversity. It is real just as sexes and species are real.

And because it asserts that race is a real, biological phenomenon caused by evolution, it also asserts that it is plausible that races vary not only in physical traits but also in psychological traits such as cognitive ability and self-control. The view that races differ from each other in psychological traits and tendencies at least partially because of genes is hereditarianism. Hereditarianism is a subset of race realism which consists roughly of the following propositions.

Race is a biological phenomenon. Humans vary genetically in predictable, patterned ways that largely conform to popular racial categories.

Races vary both in physiological and psychological traits and tendencies.

Racial disparities, which are large and numerous, are caused by a combination of variables, including underlying differences in cognitive and behavioral repertoires.

In this article, I hope to convince the reader that not only is hereditarianism reasonable, but also that not taking it seriously is potentially calamitous because it allows implausible and pernicious narratives about pervasive racism to flourish. For without reasonable competitors, such narratives proliferate like bacteria in an unclean wound, destroying the body politic by undermining trust in important institutions and promoting animosity against whites and other successful races.

It is true that some conservative social constructionists and culture-only theorists (i.e., non race realists) have pushed back against the excesses of racial progressivism. But their efforts are severely limited by their inability or unwillingness to discuss the recalcitrant underlying race differences in measured cognitive ability and violent crime that make large outcome disparities inevitable. Wanting to avoid controversy and disrepute, they refuse to use the best weapons in their armamentarium. The result is that their attacks are ineffective.

Estimating the cost of allowing the progressive racial narrative to thrive at universities, corporations, and media outlets is exceedingly difficult, but this cost is almost certainly higher than the (much feared) cost of promoting candid conversations about race differences. Thus, although the first and primary reason people should defend race realism is because it is more plausible than its rivals, it is also a crucial part of rebutting popular accusations and mendacities about the West, for until our intelligentsia is honest about the underlying reality of racial variation in socially consequential traits, misleading narratives of one kind or another will prevail. And reality will remain hidden in the gloom of our self-imposed ignorance.

Race is not (only) a Social Construct

Since at least the 1940s, intellectuals have raised objections to the concept of race, with more enthusiastic dissenters declaring it a dangerous and divisive myth that encourages invidious prejudices and ethnic factionalism (See, for example, Montagu, Livingstone & Dobzhansky, Sesardic, and Winegard, Winegard, & Anomaly for discussion). These dissenters were eventually so successful that their view, once an outlier, is now the mainstream view.

Before challenging their claims, it’s worth noting that a very common strategy among race skeptics is to demolish a caricatured version of “race,” insisting that since that version doesn’t exist, social constructionism is the only viable alternative. But this would be like refuting a platonic conception of species and then claiming that species therefore don’t exist. Race realists do not believe that races share some kind of mysterious essence, nor do they believe that races are discrete and discontinuous. Instead, race realists posit only that racial categories pick out predictable and patterned biological variation. Race realism is no more committed to mysterious metaphysics than is species realism.

There are, of course, social constructionists who grapple with a more plausible version of race realism, and they have forwarded at least three serious challenges: (1) human variation is almost exclusively clinal; (2) human variation is not correlated; and (3) human variation between groups is very small compared to variation within groups. Unlike straw man arguments about racial essences, these challenges are reasonable, but either false or misleading. Furthermore, current evidence about the relation between genetic variation and self-identified race and ethnicity and the geography of one’s ancestors has refuted the claim that race is merely a social construction.

Variation is predominantly clinal. The claim that human variation is almost wholly clinal and thus inconsistent with the traditional concept of race has been around for many years. In 1962, for example, Livingstone asserted, “There are no races, only clines” (p. 279) Modern scholars often repeat some version of this argument, stressing the gradual blending of human groups into one another. For just one of many available examples, in a recent textbook on physical anthropology that contends that race is not a biologically meaningful concept, the author wrote that because “biological traits generally follow a geographic continuum…,” humans “cannot be subdivided into racial categories.” The assertion that human variation is gradual is largely, though not entirely, correct. But the claim that this invalidates the concept of race does not follow.

Scientists classify many variables that are continuous into discrete categories, understanding that there is fuzziness on the boundaries and that although the categories are not arbitrary, the precise nature of their divisions is. Chronological age is continuous, but that does not mean that the categories “infant,” “adolescent,” and “adult” are “biologically meaningless.” In fact, they are quite meaningful, and, like other reasonable classifications, they provide inferential potential. That is, they increase our knowledge about the individuals who belong to them. If Tony said, “I’m in the car with an infant,” we would know (in a predictive sense) more about the passenger of the car than we would if Tony said, “I’m in the car with a person.” Similarly if Tony said, “I’m in the car with an African American,” we would know more about the passenger of the car.

Because the lines of each division of a continuous variable are somewhat arbitrary, there will be reasonable debate about where one category should end and another should begin. Reasonable people might argue that infancy should end at two and other reasonable people might argue that it should end at three. But these debates don’t vitiate the use of the categories altogether. And they don’t mean that the classifications are anarchical. No reasonable person would suggest that infancy should extend until a person is twelve years old.

Consider another example. Color is largely continuous, but societies classify various wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation (or perhaps it is more accurate to say that they classify various phenomenological sensations) into discrete color categories. We use the words red, blue, green, purple, and pink quite fruitfully and without confusion in ordinary discourse. On occasion, debates arise. Is the dress red or purple? But this doesn’t mean that red doesn’t actually exist or that purple is entirely socially constructed.

Therefore, even if we imagined, arguendo, that human variation was entirely clinal, then it would be similar to many continuous variables that we divide into discrete categories for ease of understanding. And it would be socially and scientifically reasonable to categorize it into racial groupings. If, for example, humans from central Africa all the way to Northern Europe created a perfect cline (they do not), then it would not be distortive to divide that cline into different categories, since people at 51 degrees N latitude would be more similar to people at 48 degrees N latitude than they would be to people at 10 degrees N latitude. There would be fuzziness and debate about the boundaries, but the categories would not misrepresent reality.

However, the situation for social constructionists is even worse than this because human variation is not, in fact, entirely clinal. Geographic barriers such as the Sahara Desert and the Pacific Ocean have impeded the free movement of humans, resulting in some discontinuities. Some of these barriers are large and/or imposing (e.g., Sahara); and some are small and/or permeable (e.g., rivers and marriage rules). As Bruce Lahn and Lanny Ebestein wrote:

Anatomically modern humans first appeared in eastern Africa about 200,000 years ago. Some members migrated out of Africa by 50,000 years ago to populate Asia, Australia, Europe and eventually the Americas. During this period, geographic barriers separated humanity into several major groups, largely along continental lines, which greatly reduced gene flow among them. Geographic and cultural barriers also existed within major groups, although to lesser degrees.

These discontinuities gave rise to the patterned phenotypic variation that caused humans to notice race differences and to attempt to classify them in the first place. And the classifications they devised were not arbitrary or motivated chiefly by racial animus. Rather, they were motivated by a sincere desire to understand human variation after noticing that human populations are slightly but predictably different from each other.

Variation is not correlated and categories are arbitrary. Jared Diamond, the eloquent and wide-ranging scholar, forwarded a popular version of this argument, writing that “There are many different, equally valid procedures for defining races, and those different procedures yield very different classifications.” So, for example, we might think that a classification based on skin color is objective and indisputable.

But if we chose a different variable such as antimalarial genes, our once obvious and unassailable categories would be upended and rearranged. Swedes would be “grouped with Xhosas but not with Italians or Greeks.” Race, therefore, is a factitious byproduct of our lust for classification with deleterious consequences for minorities, and it should be rejected.

But this would be like claiming that current biological taxonomies are arbitrary or discardable because one could, if one wished, formulate a scheme in which bats and blue jays (flying animals) are in one group and rats and ostriches are in another (non-flying animals). Biological classification is generally not based on one characteristic; and those who contend that race is a real category rely upon evolutionary history, genetic profiles, and phenotypic profiles, inter alia, to make their categorizations, not skin color alone. This does not usually result in obscure or esoteric classifications; and, in fact, the resulting classifications largely correspond to popular intuitions about racial categories because genetic variation, evolutionary history, and phenotypic variation are related to each other. Phenotypic variation reflects underlying genetic variation which in turn was caused by evolution (among other forces).

Human variation between groups is small compared to within. The geneticist Richard Lewontin forwarded the most influential version of this argument in a 1972 article, in which he wrote, “Since such racial classification is now seen to be of virtually no genetic or taxonomic significance either, no justification can be offered for its continuance.” Some variant of this argument remains a virtual catechism among those who deny the importance or validity of racial classification. And although it might sound superficially compelling, the leap from the assertion that variation is greater within than between racial groups to the assertion that race is of no genetic or taxonomic significance is logically unjustified and empirically erroneous.

In a 2003 article, A. W. F. Edwards dubbed this argument “Lewontin’s fallacy,” noting that “the information that distinguishes populations is hidden in the correlated structure of the data.” In other words, it is the pattern, the correlated differences, that are genetically and taxonomically important and that allow various methods of analysis to predict self-identified race/ethnicity from genetic data with remarkable accuracy. For a simile that’s not too misleading, racial variation is like a melody: It is the structure of the notes, not the notes themselves, that is important. Four version of the same melody in different keys are easily recognizable so long as one hears enough of the melody. The significance of race, like the significance of a melody, is in the pattern.

Again, race realism is not committed to an extravagant ontology. It does not claim that races are discrete, non-overlapping biological categories. Instead, it merely asserts that racial categories, like many other fuzzy categories, are useful for organizing human genetic and phenotypic variation. And the classifications are useful because racial categories largely correspond to geographic ancestry which largely corresponds to self-identified race/ethnicity.

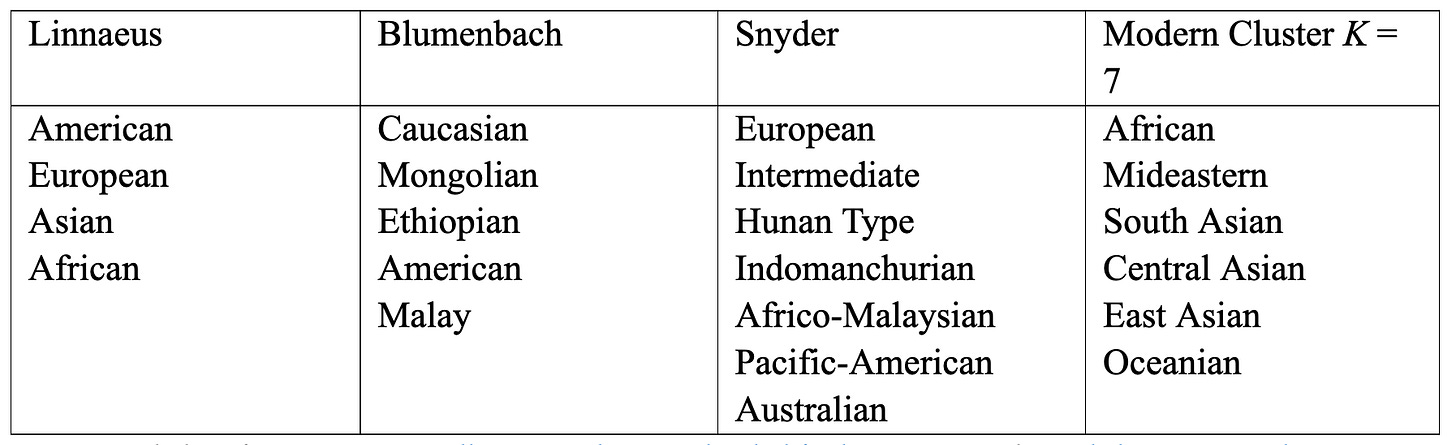

Some counter that race realism is confused because race realists do not even agree on the number of races. But this is a common problem in classificatory systems. Some people lump; some people split. Some people see red; some people see crimson and vermillion and cardinal and cranberry. A universally agreed upon racial taxonomy is unlikely, and the racial classifications a particular person uses will inevitably depend upon his interests. But this does not mean that the classification is arbitrary, anarchic, or entirely socially constructed; it simply means that the classification, like other fuzzy classifications (e.g., species, colors, ages, genres of fiction, et cetera), depends upon human motivations.

Race exists not because clever racists in the enlightenment perpetrated a fraudulent racial hierarchy to justify their bigotries, but because human populations evolved in different environments and ecologies; consequently, they evolved slightly different characteristics.

The most obvious is skin color, which lucidly illustrates the point. Races cluster geographically on skin color, and this clustering is strongly related to exposure to UV radiation. Dark skin appears to provide protection from radiation while light skin appears to facilitate absorption for vitamin D synthesis, though it may also have evolved through sexual selection.

Race realism is a straightforward and inescapable consequence of taking Darwinism seriously. Many progressives proudly wave the Darwinian banner when ridiculing conservatives for creationism or other benighted beliefs, but they quickly furl it when the discussion turns to race or sex. This selective celebration of Darwinism may be politically convenient, but it is not scientifically or philosophically commendable.

Races Differ Psychologically

Although the orthodoxy is stridently opposed to race realism, it does not deny that human populations (the euphemism it uses instead of race) vary physically. The differences in skin color, hair texture, facial structure, and other physical traits are simply too conspicuous to reject. However, it often denies that human populations vary psychologically, and it vehemently denies that they vary psychologically because of genes. This is an important distinction. Theorists can forward claims about human psychological differences without widespread disapprobation so long as they include the comforting assurance that such differences are almost entirely culturally caused. Hereditarianism must be rejected.

And so it is. Often with a fleet of moral accusations and (plausible) threats of perpetual unemployment, at least in academia. But although these tactics are effective at stifling debate, they do not change reality. The theory and evidence for hereditarianism is strong and growing by the year. Race is real. And race differences in psychological propensities and cognitive repertoires are likely common and heritable, with consequences that are not easy to dismiss.

The best studied race difference is the difference in cognitive ability as measured by various IQ tests and other related instruments. Although there are a variety of such differences across groups, the one that compels the most attention is the difference between Blacks and Whites, especially in the United States. Currently, Blacks and Whites are separated by about 15 IQ points or roughly a standard deviation. As Earl Hunt wrote in his mainstream textbook on intelligence, “There is some variation in the results, but not a great deal. The African American means [on intelligence tests] are about one standard deviation unit…below the White means…”

These differences showed up soon after the invention of reliable tests of cognitive ability and have remained relatively, though not perfectly, stable across time. They are, one might say, intransigent. Optimistic scholars often point to a narrowing of the B-W gap caused by Black gains in the second half of the 20th century, but such gains appear to have paused, and the gap remains quite large.

Of course, the mere existence of a phenotypic difference between groups does not confirm genetic causality. And scholars have debated the etiology of race differences in IQ, often with great fervor, since they became widely known. The two broadest causal theories are called environmentalism and hereditarianism. Environmentalism claims that genes account for little or none of between-group differences (20% or less), while hereditarianism, as previously noted, claims that genes account for significant proportion of between-group differences (21% or above).

Hereditarianism is supported by many lines of argument, including high within-group heritability, transracial adoption studies, persistence of differences, Spearman’s hypothesis, tests of measurement invariance, admixture studies, different proportions of target alleles in mental abilities, and even MRI studies. Some of these are persuasive; some are only suggestive. But all support the hereditarian position that a not insignificant proportion of group variation (20% or more) is caused by differences in genes. Here, I will focus on high heritability and admixture studies, which are possibly the two strongest lines of evidence.

Heritability is an estimate of the proportion of phenotypic variation in a particular time and place that is caused by genetic variation. Intelligence is consistently one of the most heritable psychological traits, with estimates often exceeding 70% in adult samples. This means that 70% of the variation in intelligence is caused by differences in underlying genes (in the place and time of the sampling population). Importantly, heritability of IQ is similar among different racial groups (moderate to high).

Many scholars have contended that within-group heritability cannot be uncritically applied to between-group heritability. The mere fact that a trait is highly heritable within one race does not mean that group differences are caused by genes. Perhaps, for example, the environment for Blacks in the United States is so deprived and degraded that it uniformly suppresses their intelligence vis-à-vis Whites. This is often illustrated with an infamous example of corn seed that is planted in two pots with different soils, call them A (fecund) and B (impoverished). Suppose that the plants vary both within and between pots and that the within-pot variance is 100% heritable (caused solely by genes). We cannot say that the between pot differences are caused by genes as well because the soils are different. In fact, the between pot variation could be 100% environmental!

This thought experiment can be useful for poking and prodding our intuitions, but like other thought experiments, its utility depends on context. And in the case of the B-W IQ gap, the thought experiment is worthless or even misleading since it is implausible that Blacks and Whites inhabit entirely different but uniform environments. And even if one had an extremely pessimistic view of the United States, a view in which the country is still haunted by widespread racism, the analogy between a race whose median income is over 40,000 dollars and whose plight has been assiduously addressed for at least half a century and corn seeds planted in barren soil stretches credulity.

Furthermore, within-group heritability does have consequences for thinking about between-group heritability. As within-group heritability increases, the size of the required environmental difference to account for between-group differences also increases. For example, a standard deviation difference between groups on a trait with 50% within-group heritability (and between-group heritability of 0%) requires an environmental difference of 1.414 standard deviations. And if the within-group heritability is 80%, then the required environmental difference is 2.236. It is difficult to imagine an environmental variable or variables that meet these lofty demands.

A commonly forwarded environmental variable presumed to account for the IQ gap is socioeconomic status. Data from a variety of studies indicate that the SES (a composite variable that considers parental income, occupation, and educational level) gap between Whites and Blacks is roughly d = .66. Thus, as Russell Warne writes, “these socioeconomic status differences account for only 7.3% to 47.6% of the environmental variance” required to explain the gap if the between-group heritability is zero (i.e., is not partially genetic). And this is being excessively charitable since the causal relation between SES and IQ is almost certainly from IQ to SES more than it is from SES to IQ. In other words, the environmental difference in SES is causally related to IQ because IQ causes lower SES and not because SES causes lower (or higher) IQ.

When we encounter highly heritable traits that reliably differ between groups and appear largely unaffected by environmental intervention, it is reasonable to believe that the group differences are at least partially genetic in origin. This heuristic is not perfect; few heuristics are. But it is reliable enough that those who challenge it should face an imposing evidentiary challenge. Fanciful thought experiments are not a substitute for rigorous examination of real-world evidence. And, to date, the totality of evidence does not support the environmentalist position. In fact, most of the evidence supports hereditarianism.

Still, this is an indirect source of evidence and argument. Admixture studies are more direct and compelling. These use populations whose genetic ancestry varies (i.e., whose genetic ancestry is from different areas of world) to relate the proportions of admixture to outcome variables such as intelligence. The main idea is that individuals who have higher proportion of admixture from an ancestral group should more closely resemble that group than individuals with a lower proportion of admixture. For a non-human example, if a population of dogs hybridized with grey wolves, we would predict that the dogs with higher proportions of admixture (wolf ancestry) would more closely resemble the grey wolves than those with lower proportions of admixture.

In the United States, Hispanics and Blacks are both highly admixed. Hispanic ancestry is 55-70% European (the rest is from the Americas and Africa); and Black ancestry is 15-25% European (the rest is almost completely from Africa). Hereditarianism predicts that since the intelligence of Europeans is higher than Africans or Natives Americans, Blacks and Hispanics with higher levels of European ancestry should have, on average, higher intelligence (as measured by IQ tests).

The best studies have indeed found a positive correlation (r = .23 to .30) between intelligence and European ancestry, consistent with hereditarian predictions. These studies are all limited in various ways, of course, but they do address a common objection: Perhaps the European admixture is correlated with intelligence because it is correlated with skin color; and skin color elicits varying degrees of discrimination. People who have more European ancestry are, on average, lighter skinned; therefore, they face less intense racism than those with less European ancestry (who are darker skinned, on average). In Jordan Lasker and colleagues’ study, for example, they imputed skin color from genetic data and found that “Skin color was not significantly related to cognitive ability in any of our models which included genetic ancestry.”

Reasonable objections remain; and thus far, only a few admixture studies have been published. But the best studies strongly support the hereditarian hypothesis; and none of them undermine it. A fair-minded person should update his or her views after examining these data.

Peer-reviewed evidence about other psychological differences among races is mixed and often poor quality. The personality literature generally finds small—and often inconsistent—differences on the Big Five (openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, extraversion, and neuroticism); but these should be interpreted with caution because personality research, especially that which relies upon self-report, is riddled with problems. Furthermore, as Emil Kirkegaard argued, “…the findings [of small personality differences] should be viewed with suspicion in light of existing stereotypes, which tend to be especially accurate for demographic groups.” The point, of course, is not that these stereotypes are necessarily true—but that they suggest differences which should be researched more carefully.

Charles Murray, in his book “Human Diversity,” provided tantalizing evidence of race differences in cognitive and personality variables by analyzing variation in the frequency of target alleles among populations using Phase 1 of the 1000 Genomes Project. These target alleles were identified by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were associated “an increase in magnitude or intensity” of various traits, from diseases to mental abilities.

First, Murray examined group differences in target allele frequencies within the same race (e.g., Chinese and Japanese) using SNPs associated with schizophrenia. The correlations were quite large, .98 for African groups (African Americans and Kenyans), .98 for Asian groups (Chinese and Japanese), and .97 for European groups (British and Italians). The proportion of chromosomes that possess the target alleles in the sub-groups for each race is very similar. But when Murray conducted the same analysis between races, the “landscape is completely different,” with smaller correlations of .74 between African and Europeans, .81 for Asians and Europeans, and .70 for Africans and Asians.

Then Murray operationalized “large difference” in proportion of target alleles between groups as .20 (rounded up from .186). That is, if Europeans had a target allele proportion of .5 and Asians had a proportion of .7, that counted as “large.” For cognitive traits, over 30% of target alleles from each comparison, e.g., African compared to Asian, were large. For personality features, which included measures of adventurousness, alcohol consumption, general risk tolerance, risk-taking tolerance, life satisfaction, positive affect, subjective well-being, and well-being spectrum, the respective percentages were 42% for the African-Asian comparison, 38% for the European-African comparison, and 35% for the Asian-European.

The meaning of these target allele differences is currently impossible to know; but they suggest that we will find many small to moderate behavioral and cognitive differences among human races that are caused at least partially by genes. Race is more than skin deep. As Murray noted, “Virtually all traits, whether physiological, related to disease, or related to cognitive repertoires, exhibit many large differences in target allele frequencies across continental populations [i.e., races].”

Race Realism and its Discontents

Humans vary across the globe not only in physical appearance, but also in language, in clothing, in literature, in government, in architecture—in all the myriad ways humans organize and enhance their lives and societies. As Nicholas Wade, in his unfairly maligned “A Troublesome Inheritance,” wrote, “…the most significant feature of human races [is] not that their members differ in physical appearance but their society’s institutions differ because of slight differences in social behavior.”

This variation (diversity) is of course recognized by academics and those on the political left—and is singled out as something meriting enthusiastic celebration—but is almost invariably ascribed to environmental causes. Sometimes these proposed environmental causes are almost random, as when a scholar attributes differences between West and East to some philosopher or another; and sometimes they are more predictable as when a scholar attributes differences between countries and continents to the availability of resources (e.g., domesticable animals, crops for agriculture). But however predictable or aleatory the causes, they are almost invariably environmental. (There are some laudable exceptions that are carefully worded.)

Race realism, however, contends that the vast diversity of human culture is caused not only by environment and caprice, but also by genes. Culture is not randomly associated with human populations, nor is it foisted upon them by a few singular geniuses or tyrants; instead, it develops from them organically like a bird’s nest or a spider’s web. It is, in some sense, an extended phenotype, an extension of the human organism’s body and mind. This is not a perfect analogy. Unlike a bird’s nest or a beaver’s dam, human culture can also evolve rapidly. And human behavior is much more plastic than a bird’s or a beaver’s. But humans are not blank slates; and the cultures they create are reliably related to their underlying traits.

A simple and uncontroversial illustration of this point is the difference between the culture of teenagers and the culture of adults within the same society. Adults recognize, and often lament, that adolescents create and consume a culture that is different from the culture that adults create and consume. (Of course, adults also create many of the products that teenagers consume because it is a lucrative business.) There are, of course, several explanations for the cultural difference between adults and teenagers, but an important one is that teenagers and adults have slightly different physical and psychological traits. What is true of the difference between adult and teenage culture is, mutatis mutandis, true of the difference between the cultures of human populations.

One potential example. There are persistent and well-studied differences in self-construal and collectivism between the West and the East such that the West is more individualistic and independent than the East. Theorists have often attributed these differences solely to cultural responses to environmental challenges. But the race realist would forward a different hypothesis: Small, reliable genetically caused cognitive and personality differences between Europeans and Northeast Asians lead to profound and fascinating cultural differences. More specifically, differences in environmental challenges and in cultural responses to those challenges led to genetically caused differences in personality and cognition, and these likely led to heightened cultural differences.

Of course, some cultural differences are random and not related (in any interesting sense) to underlying variation in genes. But a useful heuristic is that persistent and widespread cultural differences are at least partially genetically caused. Everything from aesthetic sensibilities to rule of law to style of government is caused by differences in psychological propensities, which, in turn, are caused by some unknown combination of genes and environment. This is true for individuals, and it would be miraculous if it weren’t also true of races.

In principle, many evolutionary theorists claim to accept this perspective because they claim to be guided by gene-culture coevolutionary theory; but in practice, they often go to remarkable, even absurd lengths to deny it. For example, in “The WEIRDest People in the World,” a book that attempts to explain human psychological variation and the peculiarity of the West, Joseph Henrich argues that “…genes probably contribute little to contemporary variation” and that “…if they do, they may be pushing in the opposite direction to that typically presumed.” The book also virtually ignores well-known differences in cognitive ability between the Europeans and other populations, which, although debated and controversial, have been better studied than most other (cross-national) traits and reliably predict many apposite outcomes, including GDP, innovation, Nobel Prizes, pollution, crime, and corruption.

Henrich is not an outlier, and the point here is not to malign him or his work unfairly (the book is quite good), but rather to illustrate how powerful the taboo against race realism is and how much it distorts modern thinking about these topics. The notion that the differences between Europe and other civilizations are almost entirely caused by cultural forces is prima facie implausible, and the only substantive argument Henrich offers against the genetic theory is that WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) psychology largely evolved in charter towns and free cities, which were cauldrons of disease and death, therefore selecting against “a psychology adapted to dense populations, impersonal markets, individualism, specialized occupational niches, and anonymous interactions.”

This argument is implausible for a variety of reasons, and it seems likely that at least some of the WEIRD psychological repertoire evolved before Christianity (though, of course, humans continued to evolve, both culturally and genetically, through the middle-ages and into the modern industrial age). But even if one were to accept it, the differences between nations and civilizations in IQ is almost certainly at least partially genetic in origin. Thus, at minimum, genes play some role in psychological variation across the globe (within and between countries and civilizations). However, the one recent mainstream book that attempted to make the case that genes play a role in cultural differences, namely Nicholas Wade’s “A Troublesome Inheritance,” was vilipended by scholars and pundits, many of whom had clearly not read it. Wade’s reputation suffers to this day. It’s not surprising that ambitious professors strive to avoid his fate.

Race realism is discomfiting because it contradicts contemporary dogmas about human equality. Races, like individuals, are not the same. And because they are not the same, they will create slightly different cultures and have different social outcomes. In the West, vast disparities in income, wealth, and crime are almost exclusively attributed to ubiquitous racism, but race realism rejects this narrative as implausible and divisive. Systemic racism in the West, although often invoked as a nearly omnipotent force, is virtually non-existent. In fact, one of the rare, obvious examples of systemic racism is affirmative action, which actively favors Blacks and other “victims” of oppression in the United States.

And yet, many who are suspicious of systemic racism object to race realism and hereditarianism because they view them as unseemly and factious. Indeed, even many conservatives appeal to culture or father absence when attempting to explain intransigent race differences. This is almost certainly expedient since honest discourse about race is currently unpopular and often inimical to one’s career. Nevertheless, if race realism is correct, all attempts to deny race differences will succeed only in the way that painting over fungus on a wall succeeds. The underlying problem will remain, even if people can’t see it. And in the absence of a coherent explanation of racial disparities, the progressive narrative, a narrative that blames inequalities on ubiquitous racism and bigotry, will remain persuasive to many people. And that narrative, unchecked by more plausible alternatives, will continue to erode trust in important institutions while engendering resentment in those whom it erroneously claims are oppressed.

Conclusion

I have argued that race realism is more persuasive than social-constructionist alternatives, but it is crucial to reject crude caricatures. Race realism is not committed to Platonic metaphysics or to viewing races as discrete or wholly distinct from each other. Instead, it is committed to viewing race as a useful biological category that picks out patterns of human genetic diversity which are reliably related to geographic ancestry and phenotypic traits. Many of the attacks on race realism are therefore dismissible because they are directed against straw men. However, other challenges remain, which are reasonable but ultimately unpersuasive. Human variation is not entirely continuous, but even if it were, race is still a reasonable category. Human variation is not haphazard or uncorrelated, and racial categories are not arbitrary. And human variation is greater within than between groups, but this does not vitiate the taxonomic utility of race.

I have also argued that hereditarianism is supported both by theory and by the abundance of available evidence. Not only do humans vary in physical traits such as skin color and facial structure, but they also vary in personality and cognitive traits such as impulsivity and intelligence. A straightforward consequence is that human cultural variation is not arbitrary. Different races create slightly different cultures because they have different psychological propensities. And this has obvious relevance for many contemporary debates about systemic racism, immigration, and other race-related policies. Answers are not easy. But self-imposed ignorance, even if motivated by moral sensitivity, is unlikely to help. For the silence of race realists allows erroneous narratives about pervasive racism to proliferate. Flimsy counterarguments that reject hereditarianism are unlikely to slow their spread.

Bo Winegard is an Editor of Aporia.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

Whilst this is an excellent essay about race - and race realism - I think it is important to be clear that for many (perhaps most) white Progressives, the real psychological driver of their stance is not primarily even about race. Being anti-racism is really about signalling that you are a nicer (and more sophisticated) person than your fellow 'deplorable' white peers. It is a war of white on white and Race is just a proxy. Western middle class liberalism has long been on a headlong pathological self-destructiveness that will mystify future historians when they survey the wreckage. https://grahamcunningham.substack.com/p/invasion-of-the-virtue-signallers

So, from reading this article and other sources on the topic, it seems like the following statements are true:

1. There has never been any direct evidence that human population groups have the same average cognitive abilities. In fact, all experiments have shown otherwise.

2. The theory that all groups have the same average cognitive ability was based on ideas that seemed plausible at the time, but have become difficult to believe with current genetics data.

3. Cognitive equality was originally a fringe theory, but became popular due to ideological pressure after the second world war.

4. Many of our failed social policies were based on the assumption this theory was true.

The worst part of this, besides all the millions of people who have been hurt by our failed social policies, is what this says about human beings. Our best and brightest believed an incredibly dangerous lie, that in retrospect seems pretty silly, but vanishingly few people ever went against the grain and opposed it.