Written by Josh Konstantinos.

You may not have noticed, but we’ve invented a new mating system. It has the sexual inequality of polygamy with fertility closer to a celibate religious order. The harem without the children. The monastery without the prayers.

No one announced this revolution. There was no manifesto, no movement, no moment when the old order ended and the new one began. The Pill arrived. Women entered the workforce. Divorce was destigmatized. Dating apps were launched. Each change seemed incremental and was framed as expanding freedom, which it did. But the cumulative effect was far from positive. We still use the old words — marriage, dating, relationship — the way Russians kept calling their country the Soviet Union for months after it had ceased to exist.

In the 2005 film Pride and Prejudice, Charlotte Lucas defends her decision to marry the buffoonish Mr. Collins:

Not all of us can afford to be romantic. I’m 27 years old. I’ve no money and no prospects. I’m already a burden to my parents. And I’m frightened. So don’t judge me, Lizzie. Don’t you dare judge me.

This sentiment feels alien today. A 27-year-old woman “frightened” about her marriage prospects? The desperation of Charlotte Lucas belongs to a world so distant it might as well be fantasy.

But these pressures existed until yesterday, historically speaking. And not only for women. As late as the 1950s, an unmarried man would be passed over for promotion. Such a man was seen as unstable, unserious. Then there was the most powerful incentive of all: sex. For most of history, premarital sex was genuinely difficult to obtain. Women who had it faced social ruin. Men who wanted regular access had one reliable path: marriage. Women traded sexual access for commitment. Men traded commitment for sexual access. Neither side could easily defect.

The Pill broke the incentives driving these cultural institutions. Now, sex could be reliably separated from reproduction. The downstream cultural attitudes survived, mostly, for another generation or so. They’re now passing away.

Marriage has become optional in a way it never was before. This is genuine progress — I wouldn’t suggest returning to a world where women needed husbands to survive. The freedoms are real and worth having. But a system can be freer and also more fragile. The question isn’t whether the old constraints were good. It’s whether the new equilibrium can sustain itself.

Compare Charlotte to a woman writing in TIME magazine in 2019. She’s a surgeon, 38 years old, sitting in a fertility clinic for an egg-freezing consultation. “I have prioritized my career over my personal life,” she writes, “and when I was younger, this tradeoff felt worth it.” She’d spent her twenties and early thirties in training. Now multiple doctors have told her the same thing: she waited too long. Her chances of having a biological child are “pretty low.”

Charlotte Lucas was frightened at 27 because she had to marry. The surgeon is frightened at 38 because she didn’t. Two centuries apart, same fear, opposite causes. We solved Charlotte’s problem. We created the surgeon’s.

But the surgeon’s dilemma is a symptom, not the disease. Something structural has shifted — something driving the sexlessness epidemic, the gender wars, the ideological chasm now splitting young men and women into opposing political tribes, the collapse in fertility that mathematically ends a society. We built a new mating system. But we didn’t realize what it would cost.

A global unraveling

In the United States, the share of young adults aged 18-29 reporting no sex in the past year doubled between 2010 and 2024 — from 12% to 24%. The increase was driven by men. At the 2018 peak, 28% of men under 30 reported no sex in the past year, compared to 18% of women.

On dating apps, women’s average match rate is 31%; men’s is 2.6% — a 12-fold difference. The most desirable men receive overwhelming attention while the majority receive almost nothing.

In South Korea, the 4B movement (no dating, no sex, no marriage, no childbirth) has contributed to the lowest fertility rate ever recorded: 0.72 children per woman. Deaths outnumber births. In Japan, 40% of never-married adults aged 18-34 have never had sex. The population is projected to fall from 124 million to 87 million by 2070.

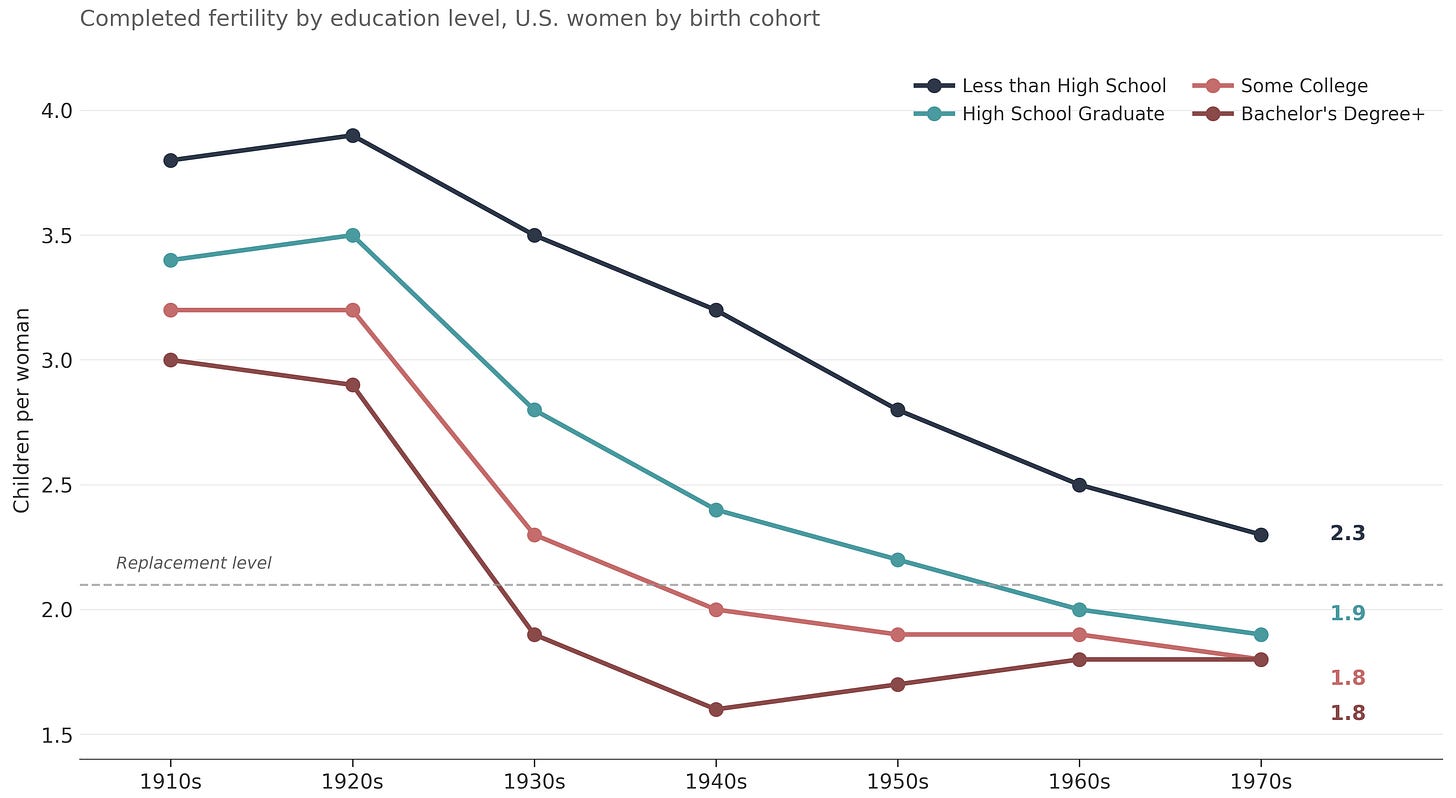

If you’re older than 45, you likely live in a world where people still got married. The figures above may feel like dispatches from another planet. They’re not. They’re dispatches from the other half of your own country. Among women born in 1980, 71% of college graduates were married by 45. Among those without degrees, it was only 52%. Marriage has become a luxury good. And all groups are converging toward the same destination: below replacement fertility.

The delay that destroys fertility

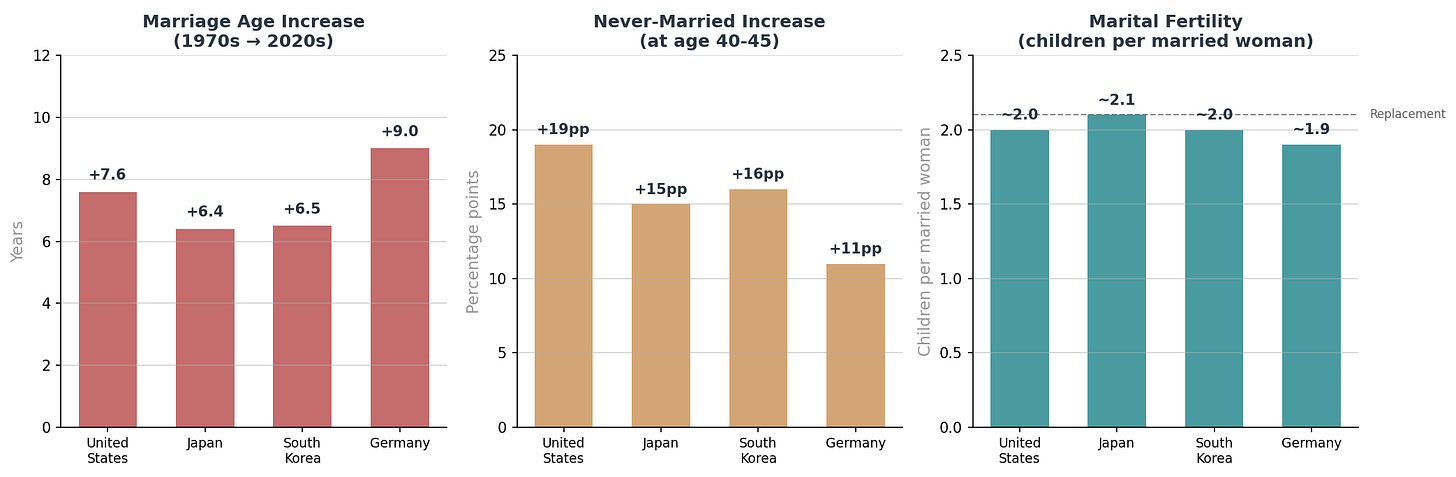

Even among people who eventually marry, the delay itself has substantially reduced childbearing. In 1960, median age at first marriage was 20 for women. By 2023, it was 28 — an eight-year increase.

Biology hasn’t changed. A woman marrying at 20 had fifteen fertile years ahead. A woman marrying at 29 has perhaps six to ten, with fertility declining sharply after 35. Dating apps extend the search; career investment pushes marriage back; each year lost is fertility lost. IVF clinics are full of women who assumed they had more time.

Births happen within durable, socially enforced pair-bonds, not serial relationships with zero exit costs. Marriage and all that it entails — shared finances, legal ties, social expectations — makes the enormous investment of raising children viable. Serial dating has no lock-in. Either party can exit at any time. Without that commitment structure, neither side has an incentive to make the sacrifices that children require. When you can get sex without marriage, and marriage without urgency, you delay.

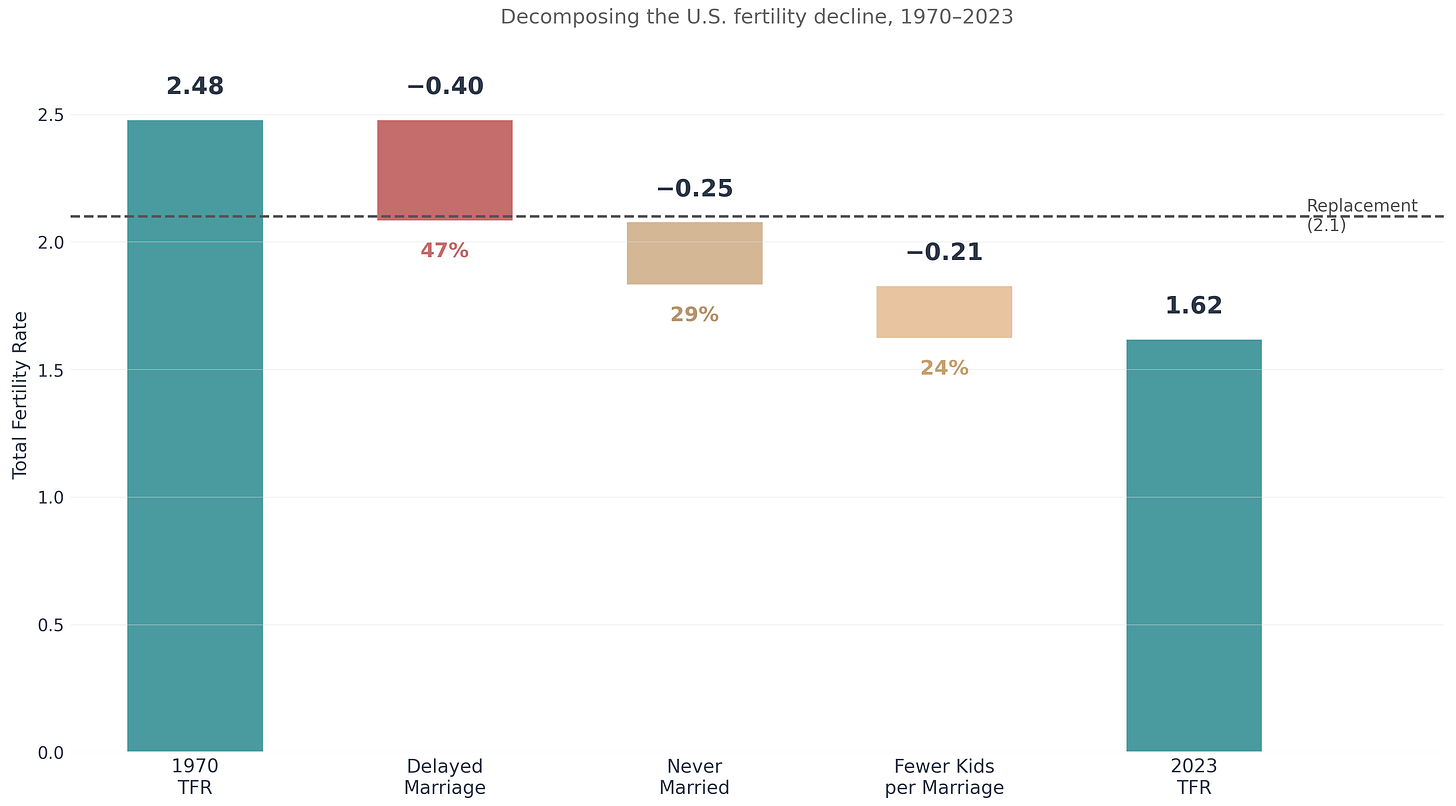

Consider the following. Of the 0.86 child decline in American fertility since 1970, delayed marriage may account for 47%.1 Never marrying may account for 29%. And married couples having fewer children? Just 24%. The collapse isn’t about family size preferences. It’s about families not forming in the first place. This finding isn’t unique to the US. Across many developed nations, the same pattern holds.

In Japan, the total fertility rate fell from 2.1 to 1.2 — but marital fertility has remained stable at approximately 2.1. South Korea tells the same story: marriage age rose six years in three decades, the never-married rate at 40 jumped from near-zero to 18%, and TFR collapsed to 0.72 — the lowest ever recorded. Germany, with a TFR of less than 1.4, matches the pattern too. Married couples still have children. The problem is that fewer people are getting married, and those who do are marrying late.

This has happened before

This may not be the first time a civilization has run into the problem of weakened norms of pair-bonding combined with (apparently) effective contraception. The Romans had their own version of the Pill: Silphium, a plant from the Libyan coast, was believed to be an effective contraceptive. (The historical analog isn’t perfect, as Roman silphium was so expensive it was limited to the elite class of Rome.)

Still, birth rates among the senatorial class declined so sharply that they could no longer sustain their own population. Senators chose to remain unmarried; those who did marry avoided having children. It preserved their wealth, limited entanglements and gave them freedom. Emperor Augustus responded with legislation: the Lex Julia in 18 BC and the Lex Papia Poppaea in 9 AD encouraged citizens to marry and have children. Unmarried men couldn’t inherit property or attend public games. The childless could only inherit half their bequests. Women who bore three or more children received legal privileges. Adultery became a public crime.

The irony was not lost on contemporaries. The Lex Papia Poppaea was proposed by two consuls, Marcus Papius Mutilus and Quintus Poppaeus Secundus, both of whom were unmarried and childless. The law encouraging Romans to have children was sponsored by men who refused to do so themselves.

The laws were deeply unpopular. Roman elites found loopholes and staged sham marriages. Marriage and birth rates among the elite did not rise significantly. Augustus had to banish his own daughter Julia for adultery, and later his granddaughter too. The quick legislative fix failed.

Silphium was expensive, so only the elite could afford it. Moreover, they had harvested it to extinction by the first century AD. The last stalk was apparently given to Emperor Nero.

Yet Rome did not go extinct. While senators avoided children, slaves, freedmen and provincials kept having them. The elite was eventually replaced: Tenney Frank’s analysis of 14,000 burial inscriptions found that by the Imperial period, a large fraction of Rome’s population descended from freedmen. These individuals learned Latin, adopted Roman law and worshipped Roman gods. Elite replacement with cultural continuity.

The same will not happen today. Contraception is no longer a luxury good. The lifestyles that once required senatorial wealth — delayed marriage, serial relationships, voluntary childlessness — are now available to anyone with a smartphone. The fertility collapse isn’t confined to an elite that can be replaced from below. It’s universal among everyone who participates in the modern mating market.

Where did monogamy come from?

If monogamy runs against the interests of the powerful, and even draconian laws from a god-emperor do not change behavior, how did the West end up with near-universal monogamy? The answer is a thousand-year social engineering project by the Christian Church.

Joseph Henrich’s The WEIRDest People in the World documents this transformation in detail. The Church’s “Marriage and Family Programme” systematically dismantled the kin-based structures that supported polygyny. The Programme banned cousin marriage out to sixth cousins, breaking up the tight clan networks that had organized society. It prohibited not only polygyny itself, but also concubinage and divorce. It required consent from both bride and groom, undermining arranged marriages that served family interests.

The Programme was strictly enforced. Kings were excommunicated for taking second wives. Nobles were denied church burial for keeping concubines. Communities were mobilized to report violations. No one was exempt.

The effects were profound. As clans dissolved, people had to form relationships beyond their kin. This created what Henrich calls “WEIRD” psychology: individualistic, guilt- rather than shame-based, high in impersonal trust and oriented toward abstract principles. The historian David Herlihy has described the Programme as “a great social achievement of the early Middle Ages”, since it enforced the same rules of sexual conduct for rich and poor alike.

Monogamy proved advantageous in competition with other societies. Monogamous societies had lower male violence, broader trust networks, and more investment in children. They out-competed polygamous ones. By the 20th century, formal monogamy had spread globally — not because it comes naturally to humans, but because the societies that practiced it dominated.

This makes sense from a game theoretic perspective: monogamy benefits society but runs against the interests of those with power to defect. High-status men benefit from polygyny. Women may even prefer to share a high-status man over exclusive access to a low-status one. The incentives favour defection. Maintaining monogamy requires external enforcement.

How we got here

In 2012, Tinder launched with a simple innovation: the swipe. Left for no, right for yes. The interface was deliberately game-like — the same variable reward mechanism that makes slot machines addictive. Within two years, the app was processing a billion swipes per day.

The designers had built something more consequential than they knew. Before Tinder, you met partners primarily through work, church and friends. You screened maybe fifty or a hundred realistic candidates over the course of your twenties. And there were still social costs attached to promiscuity.

Tinder changed things. Suddenly women had access to every male user within a fifty-mile radius — thousands of candidates, sorted by attractiveness, available for private evaluation, with zero social cost. And here’s the thing about this kind of rating system: the same people rise to the top.

The data is stark. Analysis of dating app behavior shows that women like about 14% of male profiles, whereas men like 46% of female profiles. The result is that a small percentage of men receive the vast majority of female attention. The top 10% of men get over half of all likes. The bottom 50% of men get about 5%.

Technology alone didn’t create this situation. It just removed the last constraint on a system that had been eroding for decades. Women’s economic independence removed the material need for marriage — a woman with a career doesn’t need a husband for survival. The collapse of institutional enforcement removed the cultural pressure. Church attendance fell, divorce was destigmatized, cohabitation became routine and premarital sex universal. Dating apps were the final blow: a technology that made the new equilibrium visible.

If you designed a system to maximize sexual access for high-status men while maintaining the pretense of monogamy, you couldn’t do better than the one we’ve built by accident.

The worst of both worlds

Traditional polygamy at least maintained fertility. A chief with five wives sired twenty children. Solomon had 700 wives. The Ottoman sultans populated entire empires. Childbearing was the point.

We’ve invented something different: effective polygamy without children. High-status men cycle through partners, but nobody reproduces. Why? Because reproduction requires the lock-in that marriage provides. Serial dating offers men all the benefits of access with none of the costs of commitment. And women, waiting for commitment from men who have no incentive to provide it, delay childbearing until it’s too late.

No one aside from the deeply religious would argue that we should eliminate contraception and go back to shotgun weddings. Yet cultures face an ultimate test that doesn’t care about our preferences: reproduction. A culture that doesn’t reproduce won’t exist. At a TFR of 0.72, South Korea is losing more than half its population every generation. There will be practically no South Koreans left within a few generations. Similar math applies to Japan, Southern Europe, and many Western countries.

Immigration is not a solution. Immigrants invariably converge to host-country fertility rates within a generation or two. They only maintain high fertility if they resist assimilation. The moment they adopt Western norms, they adopt Western fertility behavior too. The only communities maintaining high fertility are those that embrace traditional religions: the Amish, the ultra-Orthodox, and some Muslim groups. The future therefore belongs to the unassimilated. It will not be populated by those who subscribe to mainstream Western culture.

Technology may provide an escape route — artificial wombs, dramatically extended female fertility, or some other innovation we can’t yet imagine. But there’s no guarantee. And we’re facing the problem right now.

In No Country for Old Men, Anton Chigurh asks: “If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?” We followed certain rules: individual freedom; romantic love as the basis for marriage; the right to delay childbearing; the dissolution of social pressures that channeled people toward family formation. But they are what brought us here: to a mating system selecting itself out of existence.

In a sense, this problem will solve itself. The human race will continue — the only question is which humans. If we want the answer to include societies that value individual liberty, secular governance and equality before the law, we need to make those societies compatible with having children.

Joshua Konstantinos is the author of Sleeping on a Volcano: The Worldwide Demographic Decline and the Economic and Geopolitical Implications.

Become a free or paid subscriber:

Like and comment below.

These are the author’s estimates. They were obtained by analyzing publicly available demographic data, and are broadly consistent with those of Sarah Hayford.

'Analysis of dating app behavior shows that women like about 14% of male profiles, whereas men like 46% of female profiles. The result is that a small percentage of men receive the vast majority of female attention. The top 10% of men get over half of all likes. The bottom 50% of men get about 5%.'

What is often left out is that the same Hinge data showed a comparable skew among women, even if it was slightly lower: the top 10% of women got 46% of the likes and the bottom 50% got 8%.

A recent study showed that while women received far more swipes, they didn't swipe up more in terms of within-gender desirability (measured by swipes received) than men, and matches actually tended to be closely matched in desirability.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0327477

This is consistent with studies on traditional dating sites: while men cast a wider net by sending far more initial messages, there was a similar desirability gap between the sender and recipient for both sexes, and a similar effect of desirability on replies received.

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aap9815

The dating app argument tends to start and end at the observation of imbalanced swipe rates, but swipes alone provide zero information on who is matching, exchanging messages, going on dates, or engaging in actual sexual acts through them.

The match rates cited here are as a percentage of likes rather than total swipes. Looking at the same source that this and commonly cited swipe rates are taken from, while the median man received an average of 1.1 matches per day, the median women received 2.75. This seems like a pretty big disparity until you realize that with roughly 3x as many men using dating apps, women will naturally receive around that many more matches than men on a per capita basis.

We can go further and look at actual outcomes to find that there is also basically no difference in how many men or women in the population actually meet up with people through dating apps:

'Despite this, many men and women still find success on Tinder. According to one survey, more than 20% of millennials surveyed reported meeting someone off of Tinder. Men were more likely to use the app as well as more likely to have met someone from Tinder.'

https://www.thebolditalic.com/the-two-worlds-of-tinder/

Other outcome-based measures such as on the percentage of people who had sex with someone through a dating app in the past year, those who have dated someone through online dating, numbers of relationships started through dating apps, and the number of unique dates men and women have had through dating apps, show near perfect parity.

It's a popular notion that dating apps have facilitated 'hook-up culture', but in reality very few heterosexual hook-ups occur through them. One study found that only 20% of Tinder users had a one-night stand through it, and most of them had only one. It took about about 300 matches on average for either a one-night stand or a long-term relationship to come from it.

https://nuancepill.substack.com/p/have-dating-apps-ruined-dating

We don't have to limit our analysis to dating apps, either. We can look at population-level sexual behaviour to see if this is having the predicted effect. This narrative predicts increasing sexual inequality among men, but if we look at the top 20% of men in terms of sexual partners, we see no rise in their share of partners over time. Likewise, the 95th and 80th percentiles in lifetime or past-year sex partners aren't reporting more partners over time. Sexual partner distributions remain virtually identical between young men and women.

Moreover, we don't need to rely solely on self-reported sexual partners, as we can look to STD trends and observe no disproportionate rise among women compared to heterosexual men. Both of their STD rates have moved in tandem, contrary to what the narrative that a small percentage of men are increasingly monopolizing sexual opportunities would predict.

https://nuancepill.substack.com/p/the-chad-myth

The Church theory of why Western Civilization is W.E.I.R.D. has largely been discredited for several reasons. First of all, most of the distinctive values of The West was already present among the Pagan Gemanic and Celtic tribes of Europe for thousands of years before Jesus was even born. Norms such as an aversion to Cousin Marriage and Normative Monogamy were already dominant amongst those peoples and it was only AFTER Christianization that Cousin Marriage and Polygamy became somewhat more culturally acceptable in Western Europe. Also, having a Concubine wasn't taboo nor socially penaltized among the Nobility of Europe during the Middle Ages at all.