It's the immigration, stupid.

Pundits are declaring inflation the cause of the anti-incumbent backlash, but it's actually immigration.

Written by Frithric.

The 2024 election witnessed a massive red shift, as well as a specific shift towards Trump compared to 2020 and 2022. According to voters, the biggest issue in the 2024 election was the economy, which surpassed COVID as the primary focus. However, immigration also made substantial gains from a lower baseline.

The trouble is that a wide range of things can fall under the umbrella of the economy. By virtue of the fact they’re both simple numbers, inflation and headline GDP tend to dominate political discussion about the economy. And so the growing consensus among wonks, left-wing economists and others is that Americans just didn’t understand that their economy was doing well, or that they were more worried about inflation than unemployment. This is wrong. We had an election in conditions of once-in-a-lifetime inflation rates and relatively high unemployment: that election was 2022. And although 2022 wasn’t great for incumbents (including the Democratic Party), it was nowhere near as bad for them as 2024.

The inflation rate peaked in 2022. Yet some governments facing elections in that year gained vote share, and one of them, Portugal, even saw a stunning increase in ruling party support. The same applies to previous periods of widespread inflation, such as the 1970s. Inflation isn’t popular, but simply can’t explain the universal collapse in public confidence in democratic governments this year.

What explains the OECD-wide situation?

Any explanation for this massive turn against establishment parties, after the rally to such institutions during the immediate COVID-era, cannot be limited to the United States. It must account for aspects of the economy shared across national and trade barriers. There are already explanations for this phenomenon from left-wing wonks, but the right has been remarkably unwilling to put forward a unified alternative theory. Instead, the right has echoed or even amplified the left-wing explanations for their loss, namely, a reaction to the left’s embrace of wokeness and to the perceived state of the economy. These are insufficient; the timing doesn’t fit, and the package of cultural explanations doesn’t cross national boundaries.

Some incorrect alternative explanations:

Explanation 1. The democrats were not rewarded, as they should have been, for the real successes of their economy.

This is false. In a year that has been devastating for incumbent parties, Democratic Party avoided the worst possible outcomes likely because of high employment, an uptick in manufacturing, and pro-union policies and rhetoric.

Explanation 2. This is a normal thermostatic political correction.

Unlikely. The anti-incumbent turn this year is real, but not a natural law of politics. In 2022, incumbent parties won a number of elections.

Explanation 3. It’s AI.

Unlikely. While the AI shock might be real for some sectors, the groups so far suffering the greatest job losses to AI (market rate interchangeable content creators) have not shifted their political positions any more or less than other demographics.

Postulate 4 & 5. Inflation & Affordability.

Given that these political revolts are occurring in 2024 and not 2022, the rate of inflation is unlikely to be the cause. However, excess inflation from 2021-2024 is a more viable explanation. Still, even this is unlikely to account for incumbent defeats across the West. But immigration is, since deportation would indeed improve affordability of certain items that are of concern to voters and it was a more pressing issue in 2024 than 2022.

Thus, the 2024 elections can be interpreted as a referendum on the long-term effects of the policies implemented during the reopening after COVID lockdowns. The left-wing pundit class is converging on a theory that the anti-incumbent backlash is about inflation, which is not entirely unreasonable. However, mass immigration better fits the data because it:

Was OECD-wide.

Has difficult-to-pinpoint but real economic effects.

Relates to real wealth and wages.

Had differential impacts by country and corresponds to the actual anti-establishment backlash of those countries.

Creates a sense of chaos and cultural change.

In 2020 and 2021 there was almost no net immigration. In 2022, and then increasingly in both 2023 and 2024, Western nations took in a whole lot more migrants as governments across the West acted as if they had to make up for lost time—and then some.

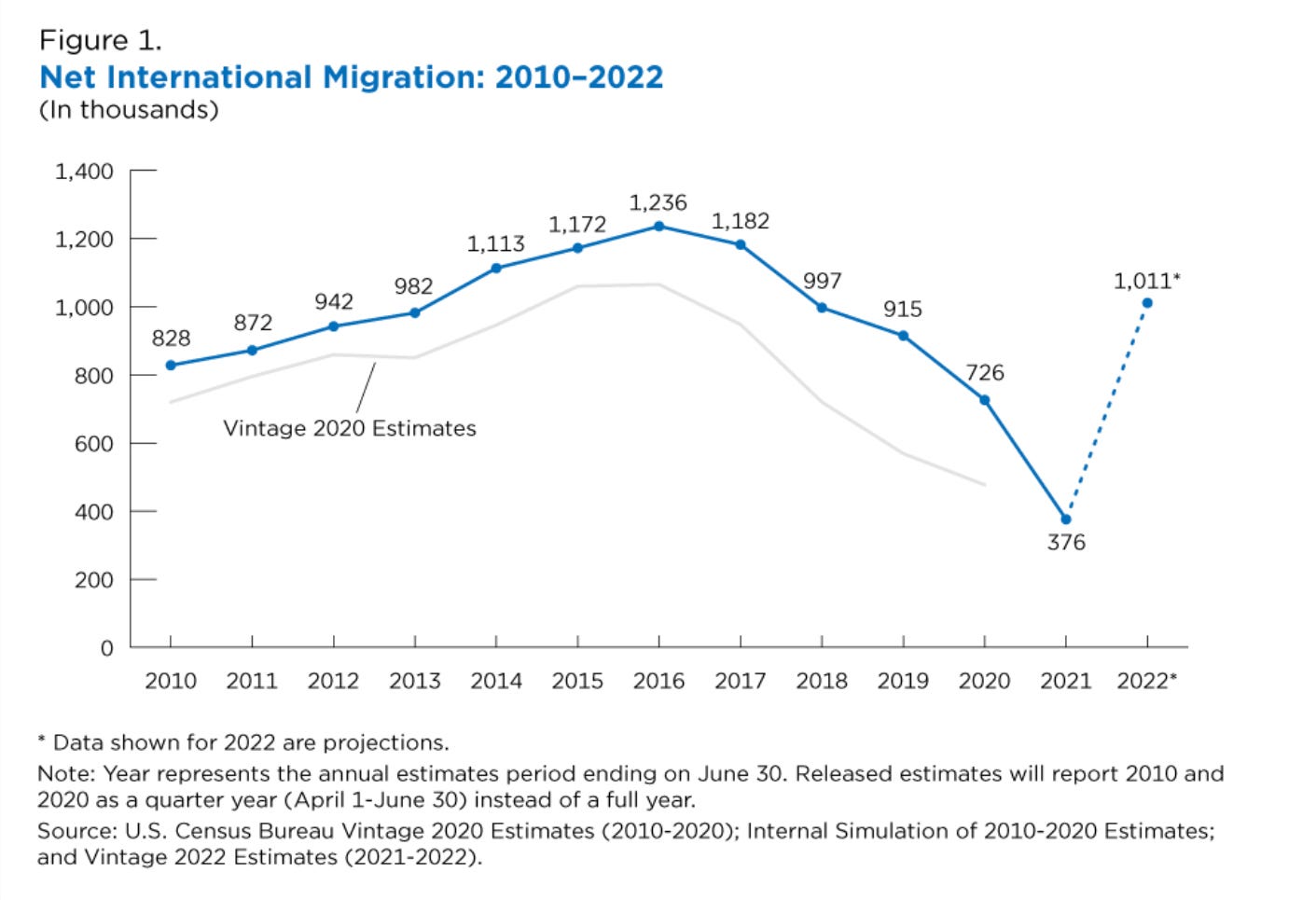

But only a few years prior, during COVID, virtually all OECD countries enforced bans on entry to non-citizens and non-residents, and for most countries, these bans were applied across the board. These travel bans were mostly lifted between 2021 and 2022. And the lifting led to an enormous uptick in all forms of immigration to the United States.

Of course, in the United States specifically, net international migration had been falling during Trump’s entire presidency, before picking up again during Biden’s. The most important chart in of the 2024 American election illustrates how the combination of Trump’s policies and COVID-19 lowered illegal immigration into the US. But the OECD-wide (indeed, world-wide) effects of COVID entry bans and migration freezing is what explains the political revolt against established governments.

The UK & Portugal had the largest post-COVID migration spikes and the largest ruling party backlashes

If we assume that inflation is the cause of the anti-establishment backlash this year, then we should expect the two countries with the largest anti-establishment backlashes to have been the ones with the worst inflation. That is not the case. Instead, the two countries with the largest anti-establishment backlashes were the United Kingdom and Portugal. The United Kingdom had inflation, but it was not excessive compared to other members of the OECD. Portugal also suffered from inflation, but it was not especially high relative to similar countries. What both of them do share, however, is that they experienced large spikes in net immigration, which began earlier than in other countries.

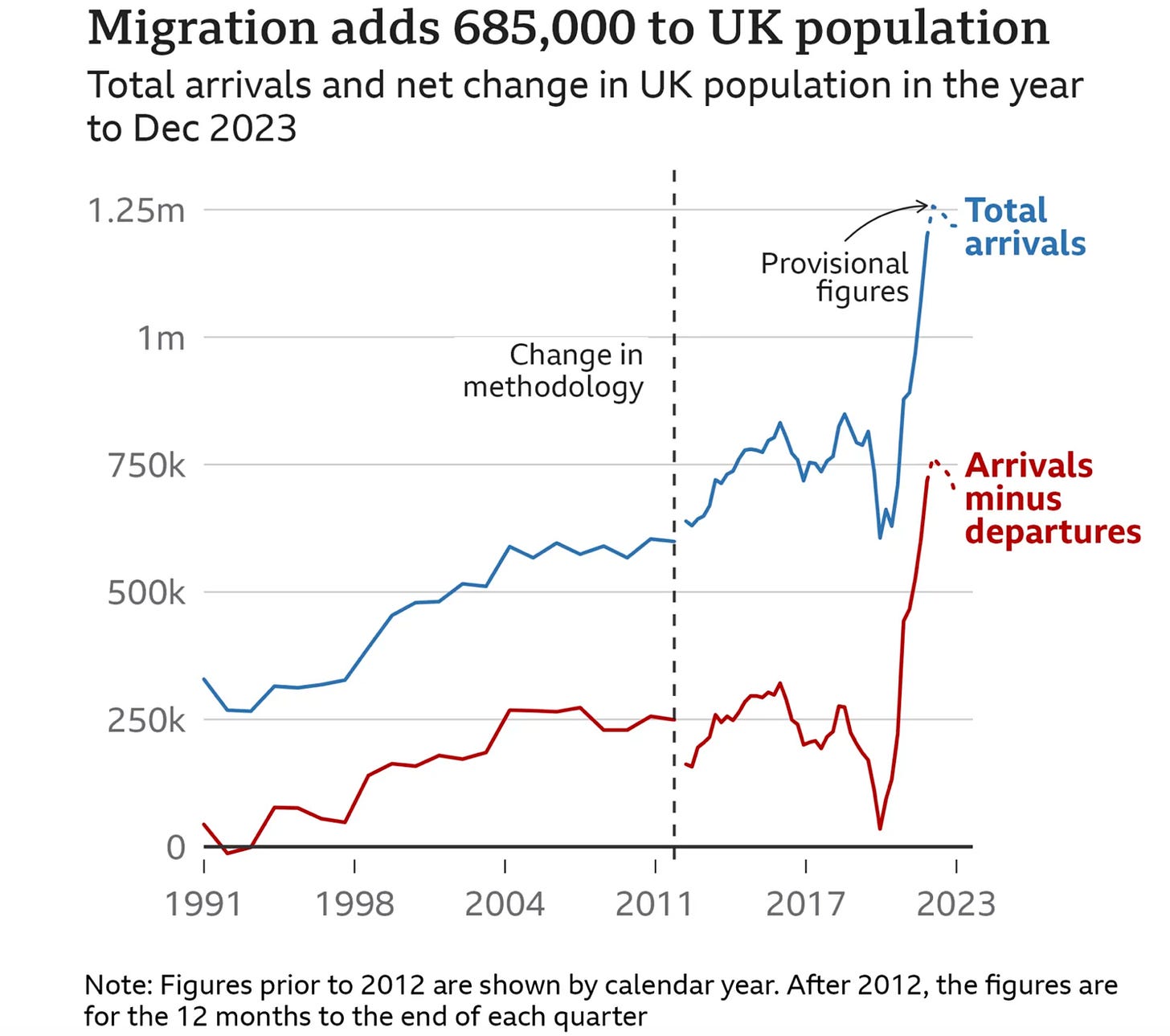

The post-COVID migration boom in the UK has roiled the country, with a number of anti-immigration riots. Although the UK was affected by the travel slowdowns of COVID, the country did not enforce either a blanket or partial ban on all non-citizen or non-resident entries. Instead, the UK relied on a temporary “red list”, which was applied with baffling arbitrariness. This meant that more than other OECD countries, when global travel picked back up after the end of lockdowns, there were few impediments (and instead massive assistance) for the surge of migrants into Britain.

The UK has gone from almost zero net migration in 2020 (for the first time in decades) to net migration levels of almost three times the yearly amounts of the decade prior to COVID. Additionally, the types of migrants coming to the UK have been of a different kind as well, with much larger amounts now coming from outside the EU for the first time in a decade.

This explains why the UK in particular has been the standout example of anti-establishment backlash, with the Conservative Party losing in a landslide, and the incoming Labour Party already facing anti-immigration riots and its leader becoming extremely unpopular only a few months after its massive win earlier this year.

The second largest political backlash of 2024 so far has been against the Socialist Party of Portugal. While the Socialist Party is on the left and the Conservative party in the UK is on the right, both governments allowed enormous surges in migration since the end of COVID travel controls. Both governments provoked a hostile reaction from voters.

What makes Portugal illustrative of the cause of the backlash is that it is a member of the Eurozone, so theoretically it should have similar policies as other member states. But Portugal has had more generous immigration policies than the rest of the continental EU both during lockdown and during reopening. Specifically it had increasing net migration from 2020 to 2021, and a very large increase in net migration during 2022, 2023 and into 2024.

Immigration is the job market

But if immigration is the issue, why did comparatively few people list it as their primary concern on election day? Possibly because the actual economic effects of immigration are diffuse and difficult to place. While others have laid out the broad array of negative effects of immigration on the British economy, I will highlight the deleterious effects it has had on the US job market, which is compounded by new forms of globalization and an economy that is dependent on government jobs for growth. This explains why much of the growth in employment since 2019 has gone to immigrants.

In 2024, there has been a growing divergence between a generally healthy GDP per capita and an increasingly discontented public, which appears to want more freedom in the job market. This is illustrated by the low “quit rate”, the rate of workers voluntarily leaving their jobs, which has fallen to below the stable state prior to the pandemic. This turn is caused by fears of a recession. Given that for native-born workers job growth has been unimpressive in 2024, despite the rosy headline numbers being reported, these fears are understandable.

COVID led to the voluntary resignation of numerous employees, a phenomenon termed “The Great Resignation”. For a brief time after the COVID shutdowns ended, the labor market was incredibly hot because of labor shortages, leading to higher wages (which were mostly offset by inflation). When the Great Resignation ended, immigration boomed, and the market cooled. (As the Kansas City Fed confirmed, this was a purposeful and desired outcome.) And since the market cooled, job satisfaction has decreased.

Many analysts claim, of course, that without immigration, nobody would fill many of the jobs in the United States, but this ignores the fact that the labor-force participation rate for prime-age men (especially low-skilled prime-age men) is staggeringly low.

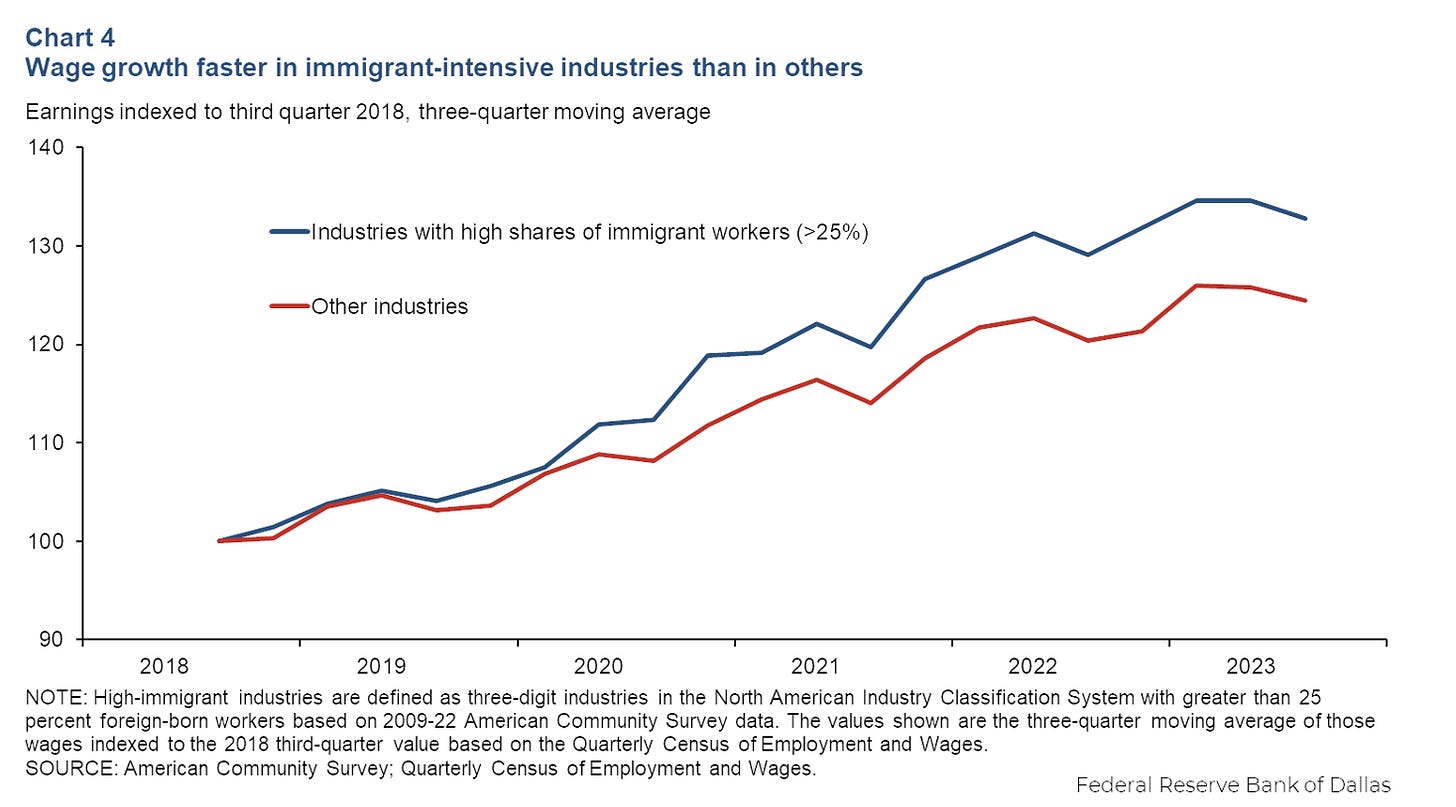

Since 2021, wages have decelerated relative to inflation in sectors and states with larger increases in immigrant workers. Some might claim this is almost inevitable, but it is not some iron law of nature, and one should not conflate a bad administration’s policies with unchangeable defaults. When Western governments moved away from generous immigration policies, and instead enacted strict border controls, things looked rather different. The labor market was tight and wages were going up.

The Banner Year of 2022

If one looked at wages one year prior, it would have been a completely different story. Immigrant-intensive industries were the ones that had seen the largest wage growth, at least when indexed to 2018. This shows that immigration shifts can rapidly depress workers’ wages.

The 2022 elections in both the U.S. and much of the rest of the OECD occurred in an economy that was less affected by recent immigration than it had been in decades. Portugal is a case in point. While I have already noted why Portugal was second only in Britain in terms of the populist backlash in 2024, this was not the story back in 2022. In that year, due to fights over the budget and political conflicts with the radical left, Portugal held snap elections. The result was that the Portuguese Prime Minister won a suprise majority.

The pressing issue of 2022 was the rise in inflation, but it did not precipitate a populist backlash the way immigration has in 2024. However, that still doesn’t explain why voters keep talking about it. Yes, inflation is shocking and certainly vexes voters, but there’s something else going on. Voters are likely using inflation as the more “respectable” way to talk about their real concerns.

Anti-Immigration sentiment has described multiple times as violence, xenophobia, hysteria, and various other dismissive phrases. In addition to the short-term rise in prices that might come from increased competition for necessities such as housing and food, the Biden administration has ramped up various schemes to assist “newcomer populations” with handouts for housing and other benefits, including just straight cash, all of which increases demands for necessities, and increases cost of living. And so complaints and worries over inflation becomes the way to discuss the political concerns about woes that will be aided with Trump’s deportations. It’s an increase in cost of living yes, but it's caused by the cost of living with immigration.

The parties which retained power through 2022 responded with a broad suite of immigrant-encouragement policies. These included Apps to request entry, ignoring the explosion of border crossings while trying to convince the public that it was fixed, record high migration levels, labour deals for migrants, and other extremely pro-immigration moves. But from the rise of the German AFD, to the return of Donald Trump to the Oval Office, to the smashing of the Conservative Party, populations have enthusiastically rejected this shift to pro-immigration policies. A Notice for the Future: those who promote such policies will be put on notice at ballot boxes across the world.

The immigration-affected economy

One of the best accounts of how an economy can decline with large-scale immigration is in a fascinating article in the Pimlico Journal, ‘Deliveroo Britain’. The author lays out a list of effects that may occur in such an economy:

In America, we are starting to see this type of economy emerging, most immediately in the trend of part-time jobs replacing full-time jobs. This trend helps to explain why people feel that their economic prospects are declining, despite the increase in job growth: their prospects really are declining. If job growth is heavily part-time, while full-time jobs are disappearing, then meaningful work becomes increasingly scarce.

But even with part-time jobs and foreign-born jobs buoying the job growth numbers, it has not been enough for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which has repeatedly revised monthly job growth estimates downward – from growing at the same rate to nearly flatlining – against rosy expectations month after month and year after year.

All of this has lead to a job search process that is tedious, lengthy, prone to rejections and incapable of finding talent. And this is devastating for wage growth because in the United States increases in annual pay primarily come from switching jobs. A period of lengthy, frustrating and fruitless job searching has borne little fruit in terms of wage growth.

A worse job market means more spent looking for a job, and the average job search involves navigating identity topics like race and the current panoply of institutionally recognized gender identities.

The archetypical 2020–>2024 Biden to Trump vote

It is dangerous to prognosticate on a “type of voter”, but I think we can do so here. Indeed, there is a type of voter that takes shape in my mind when I think of someone who punched their ticket for Trump in 2024, having punched their ticket for Biden in 2020.

They are likely old enough to have acquired some amount of net worth, but not old enough to have spent large stores of wealth. They might be married with kids, having entered middle age without being close to retirement, and while secure in their job, they are concerned about a job search process that has become increasingly frustrating. They were probably irritated by Trump’s rhetoric four years ago, but it’s been a long decade and things change. They now see Trump as better for their interests than Kamala Harris.

This voter might have been activated against the woke antics of the Democratic Party over the last four years, including the Democrats unwavering fondness towards a new wave of immigrants, Black partisans, and an increasing potpourri of sexual minorities. They might see the strange and ineffective pandering towards “White Dudes” from the Harris campaign as maladroit and off-putting. They are probably not highly educated, but they are likely proficient enough in English that they feel at least some cultural kinship towards the United States.

This voter probably disliked Trump’s anti-immigration rhetoric, or else they would have voted for him before, but they deplore the impact of the sudden increase in immigration, as compared to the benefits of an immigration slowdowns four years ago.

I am obviously conjuring an image of a working-age Latino who is likely either a first- or second-generation immigrant himself. And indeed, Latinos did shift dramatically toward Trump because they liked the way things were four years ago and felt strongly about inflation and the chaos at the border. Because of their own experiences as immigrants, they are less likely explicitly to endorse Trump’s border policies, but they enjoy the actual effects of Trump’s restrictionist efforts. They did not cast their vote for a so-called “multi-racial working-class coalition,” but rather for an American nationalist coalition aligned against leftist cultural issues, as well as and the negative cultural and economic effects of mass immigration.

So we come to a close of the Biden Administration

The actions and reforms undertaken by the Biden Administration over the last four years aimed to increase the total number of migrants, including redirecting funding and repurposing FEMA from disaster response to noncitizen resettlement. When FEMA was needed for a novel and uniquely dangerous situation involving massive inland hurricane flooding, the response was characterized by politically motivated denials of service and claims that criticisms of its handling were dangerous.

It is little wonder, then, that the fallout from immigration increases, combined with the negative effects of administrative and regulatory bloat, and the repurposing of federal and often state agencies towards increasing immigration, has resulted in the near flatlining of real household wealth for Americans.

As the Republicans in the Trump Administration enter office with a debt to CEOs of the Tech Right who are very interested in increasing high skilled immigration, they would do well to remember that the forces underlying the collapse of the Democrats’ coalition could just as easily turn against them, as has happened in Britain to the Conservative Party.

Conclusion

However, as soon as governments, economies, and Western nations reverted to the 2010s norm of lower inflation but higher, perpetual immigration flows—this time without the benefits of a zero-interest-rate policy—voters across the OECD countries responded, in some cases even rioting, in a cross-national revolt against the effects of immigration. Do not be mislead by the consensus about inflation. This revolt of cost of living was clearly about immigration. Those who mislead themselves about the negative effects of immigration will pay the price at the ballot box.

Frithric is an anonymous writer interested in learning the true mechanisms behind developing political, cultural and legislative trends.

Support Aporia with a $6 monthly subscription and follow us on Twitter.

I like this article.

I would also say that there is a certain "lag effect" in the electorate. People believe a lot of the propaganda and then when it doesn't turn out true they are turned off. Sometimes people on sub stack that "get the joke" earlier then the masses can't understand this, but there are people who only watch cable news or no news that are shocked in Summer 2024 to find out that Biden is literally demented, etc.

So the fact that 2022, a midterm with more "plugged in to the machine" voters didn't have a Red Wave doesn't mean quite as much to me, but I still like the article.

Well presented. Well argued.