Written by Noah Carl.

During the period from roughly 2010 to 2024, which has become known as the Great Awokening, radical progressives attempted to co-opt every major institution in society for the purpose of advancing their ideological agenda.

Thousands of people were demoted, suspended or fired for saying the wrong thing. Others were banned from social media and even debanked. Cherished monuments were vandalized or torn down. Police officers genuflected before protestors they were supposed to be policing. Universities issued statements that brazenly contradicted their truth-seeking mission. Authority figures started using bizarre, new-fangled terms like “non-binary” and “people of colour”. Once respected medical organisations began referring to people’s “sex assigned at birth”. And there were calls to “defund the police” just as looters and arsonists ran riot through major cities.

This insanity rightly provoked a backlash—from both people on the right and those in the liberal centre. Anti-woke institutions like the Free Speech Union began popping up. Soon there was a cottage industry of journalists and social media activists who would lampoon the latest woke absurdities. Then in 2022, Elon Musk purchased Twitter, arguably the most influential social media platform and surely the most influential among elites. He fired most of the content moderators and unbanned accounts that had previously been suspended, prompting an exodus of liberals and leftists. By 2023, companies that engaged in woke activism were subject to humiliating boycotts. And in 2024, Donald Trump won a decisive election victory after running an explicitly anti-woke campaign. Post-election polls showed that Kamala Harris’s ill-advised focus on “cultural issues” was a major reason voters backed Trump.

Of course, wokeness hasn’t been completely eradicated. And there’s a case to be made that it merely lies dormant, poised to return with a vengeance once zoomers and millennials work their way to the top of large organisations. Whether rumours of its death have been greatly exaggerated or not, it is clearly on the back foot. Stories about woke antics have slowed to a trickle. Mentions of woke jargon are down in both newspapers and academic journals. Meanwhile, Musk remains in charge of Twitter and Trump is still in the White House.

In fact, the week following Charlie Kirk’s tragic assassination witnessed an unexpected outburst of right-wing cancel culture. Dozens of people around the country were fired for making distasteful or, in some cases, fairly innocuous comments about his death. These firings were cheered on not only by right-wing influencers but also by Republican congressmen and even the Vice President, J.D. Vance. Attorney General Pam Bondi mentioned going after people for “hate speech”. And Trump himself wondered whether he should remove TV licenses from networks that are “against” him.

So far, this outburst hasn’t come close to the level of cancel culture or ideological co-option that prevailed during the Great Awokening. But it has provoked charges of hypocrisy—justifiably, in my view. Vance’s flip-flopping stands out as particularly egregious. In a major speech back in February, he said that “just as the Biden administration seemed desperate to silence people for speaking their minds, so the Trump administration will do precisely the opposite”, adding that “we may disagree with your views, but we will fight for your right to offer it in the public square”. Fast forward to September, and he told supporters that if you “see someone celebrating Charlie’s murder”, you should “call their employer”.1

Charges of hypocrisy have been levelled not only by leftists (many of whom have no leg to stand on given their own censorious tendencies) but also by people with credibility, like Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression.2

Anyone on the right who points out the hypocrisy of opposing one form of cancel culture while supporting another will soon be met with some version of the following argument: “Haven’t you heard of Carl Schmitt and the friend–enemy distinction? You have to not care about principles and just care about winning!” For those who aren’t familiar with the argument, Schmitt was a German jurist who strongly opposed (classical) liberalism and famously argued that “the specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy”.

Principles are nice, proponents claim, but relying on them is dangerously naive. And as the left has long since abandoned them, the right must do the same—at least until it has regained enough cultural power.

This makes a certain amount of sense. Many people on the left did abandon any commitment to institutional neutrality and free expression, or they allowed them themselves to be cowed into submission by zealots. And it’s true, almost trivial, that if I have a particular political vision, then people who have the same vision are in some sense my friends while those who have a different vision are in some sense my enemies. After all, my vision cannot succeed unless other visions fail (someone has to lose the election).

Ultimately, however, I’m not convinced. Principles do matter. And the friend–enemy distinction is a lousy basis for politics.

To begin with, the distinction is wildly reductive. In case it wasn’t obvious, the population does not consist of two neat groups, the left and the right, all of whose members agree with each other and disagree with the other side. Public attitudes are continuous and multi-dimensional. On most issues there is a range of opinion, with many people taking some intermediate position. And while two-party systems like the US may have less dimensionality than multi-party systems, they still can’t be summarised with a single axis, let alone a simplistic left–right binary. So who exactly is my “friend”? Someone arbitrarily close to me in multidimensional political space? And who is my “enemy”?

This is not some nerdy, academic point. Even within “the right”, there are massive divisions over tariffs, high-skilled immigration and whether Trump is a very stable genius or a national embarrassment.

Among the most fraught issues of all is America’s relationship with Israel. Although Trump and the GOP establishment remain stalwart in their support for the Jewish state, young conservatives are increasingly sceptical. A recent poll found that only 24% of Republicans aged 18–24 sympathise more with the Israelis, with another finding that half of those under 50 have a negative view of Israel. Disagreement on this issue is notoriously acrimonious. Sceptics are painted as anti-Semites, while supporters get accused of being Jewish spies—and this is despite the fact they often agree on much else. Conservative Tucker Carlson has been praised by the progressive Ana Kasparian for his criticism of Israel, while being harshly rebuked by his fellow conservative Mark Levin.3 Who are the “friends” and “enemies” in this little trio?

The second reason to reject the friend–enemy distinction is that it is antithetical to the Western (or at least Anglo-Saxon) tradition. Instead, it is the organising principle for politics in much of the non-Western World. As a popular Latin American saying puts it: “For my friends, everything; for my enemies, the law”.4

There are many backward countries where the modus operandi for politicians is: get elected; then use the levers of power to reward cronies and other ethnically or ideologically-aligned interest groups, while punishing your political enemies. This way of doing things, which is common to both the left and the right, is generally known as “corruption”. And it’s highly detrimental to society.

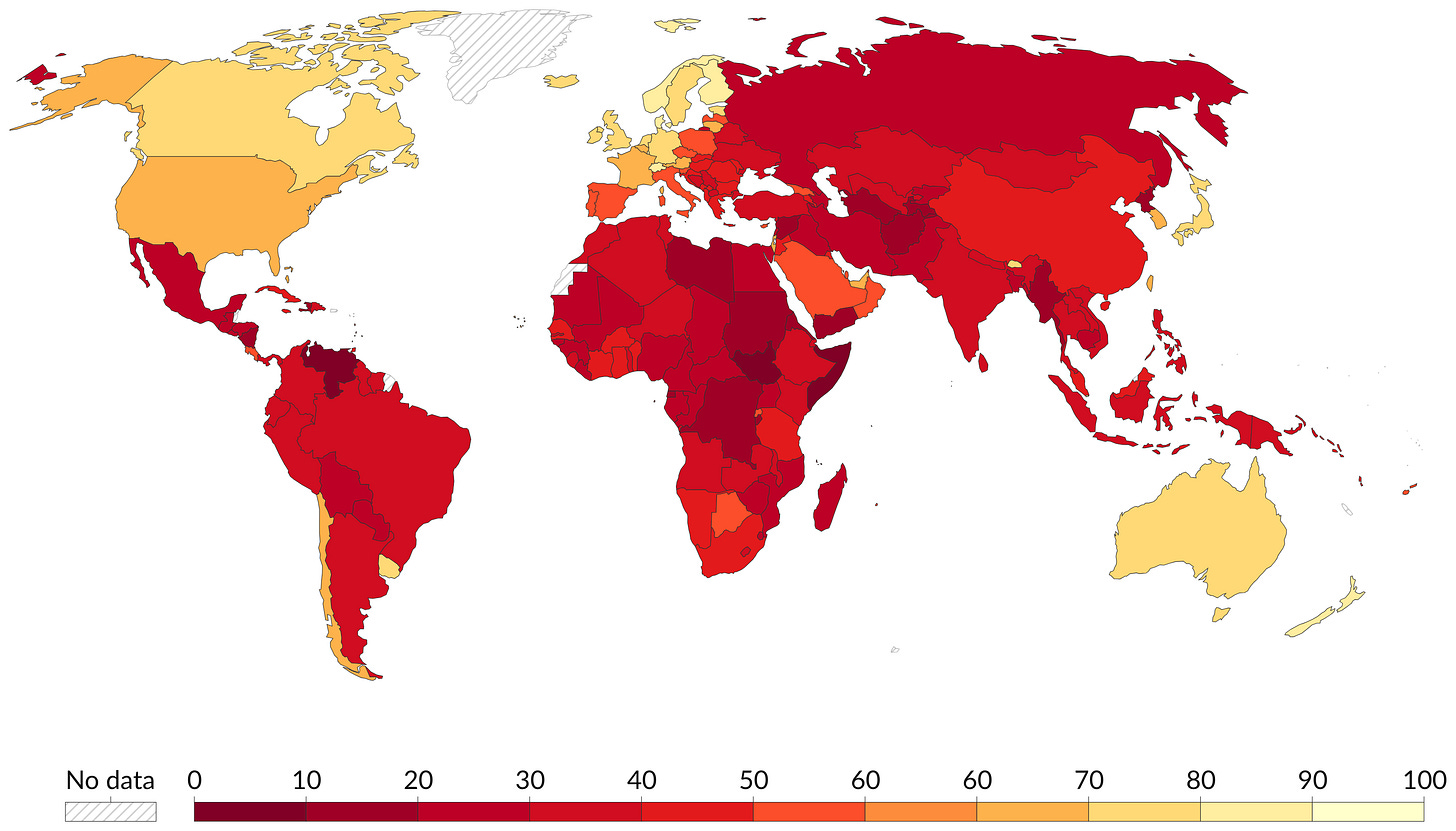

A map of more and less corrupt countries is shown above. As you can clearly see, Western Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand are among the only places where citizens do not perceive a high level of corruption in the public sector. Of course, ethnic or ideological favoritism isn’t the only element of corruption, but it’s a big part of it.

An alternative way of doing things, which gradually became established in the West over the last few hundred years5, is to have formal rules and informal norms that apply to everyone—even individuals or groups that you personally dislike. The intellectual heroes of this tradition include John Locke, Thomas Paine, John Stuart Mill, A.V. Dicey, F.A. Hayek and the American Founding Fathers. These seem like men worth emulating. By contrast, “Let’s be more like the Third World” doesn’t strike me as a winning conservative policy.

At this point, proponents of the friend–enemy distinction may offer one of several counter arguments. The first is: the left started it! Now, I think this is basically right (although Trump doing things like appointing his close family members, and hurling playground insults at his opponents, definitely didn’t help). However, just because the left started it doesn’t mean the right should continue it. Instead of concluding that, you know what, the left is really onto something with this Third World-style of politics, the correct response is to demonstrate the manifest stupidity of wokeness, while retaining political capital for issues that matter.

A more sophisticated counterargument appeals to game theory. If your side “cooperates” whenever the other side “defects”, it will soon find itself at the mercy of the other side’s exploitation. The right must therefore tactically suspend its commitment to free speech and cancel a certain number of leftists in order to restore deterrence. Perhaps it should threaten a few TV networks too.

While superficially compelling, this is not a realistic model of social behaviour. After the spate of recent firings, did you encounter any leftists saying, “Fair enough, we deserved that. We really ought to think twice the next time we engage in cancel culture”? I just saw scores of people poking fun at the right’s hypocrisy and running victory laps for having insisted the right never cared about free speech.

Rather than restoring deterrence, right-wing cancel culture seems far more likely to bolster the left’s own predilection for censorship. How? It sends the message that, yes, it’s appropriate to censor “offensive” speech.

That’s because the left and the right aren’t analogous to two agents playing an iterated game of prisoner’s dilemma. Politics is far more complicated than that. At the very least, what’s being played is an n-person prisoner’s dilemma (i.e., the public goods game) and in that case Tit for Tat-like strategies aren’t viable. Indeed, the relevant literature suggests that one of the best ways to promote cooperation in public goods games is for the players to establish rules or norms that discourage defections.

None of this means we shouldn’t fight tooth and nail against any effort to co-opt institutions under the guise of neutral-sounding jargon. For example, taxpayer funding for academic departments that amount to little more than left-wing activist centres should certainly be reviewed. Nor does it imply Antifa should have free rein to terrorise ordinary people.

Notwithstanding its conceptual shortcomings, the friend–enemy distinction helps to illuminate how politics works in much of the world, including, to some extent, the West. However, this doesn’t mean we should use it as a guide—as something to which we should aspire. The statement “man engages in predatory violence” also has some truth in it, but this isn’t a licence to go marauding through your local shopping centre. Conservatism is about preserving and gradually improving tried-and-tested institutions, not discarding them in the face of ideological subversion.

Noah Carl is an Editor of Aporia.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

I do not condone public celebrations Kirk’s death, but I recognise that people are offended by different things and there is no objective definition of “offensive” speech. For me, Vance’s February statement struck exactly the right tone.

FIRE, as it’s known, is a non-partisan organisation that does excellent work defending people’s free speech rights. Suzanne Nossel is another person with credibility who criticised the right’s aboutface on cancel culture.

This saying has been attributed to several different figures and it is unclear who said it first.

"friend-enemy distinction" has become a thought-terminating cliche. Yes, politics is a struggle, and it often involves hypocrisy. Don't be surprised if your opponent breaks the nominal rules of the game. But politics also depends on some shared norms, otherwise it would just be civil war. Establishing those cultural norms is important in the long term, even if there is a temptation to transgress them in the short term.

"While superficially compelling, this is not a realistic model of social behaviour. After the spate of recent firings, did you encounter any leftists saying, “Fair enough, we deserved that. We really ought to think twice the next time we engage in cancel culture”? I just saw scores of people poking fun at the right’s hypocrisy and running victory laps for having insisted the right never cared about free speech."

I think it is well to consider that modern western societies are beyond this point, because it reveals an underlying intend at cooperation and compromise.

All that is gone, and hence hypocrisy is simply a tool to win a zero sum game. It *may* have been seeded during Gingrich's term as Speaker, and metastasized gradually from there. Concurrently, each succeeding generation seems to have devalued ethical consistency in favor of gratifying one's own social whims--many of which are fickle and transient--consequences to social stability be damned.

I'm approaching 80. All this is becoming very, very evident to me by way of comparison over this time frame. Regrettably, it will require a period of protracted existential trauma on a massive scale to force a re-set back to mutual cooperation between opposing parties just simply to survive. Right now, each political/ideological party truly believes that yep, it *can* have it all.

Luxury beliefs, indeed.