Written by Noah Carl.

What do Madeleine Albright, the controversial US Secretary of State, and Václav Havel, the playwright and first president of the Czech Republic, have in common?

Both were born into elite Czech families in the 1930s. Albright, born Marie Jana Körbelová, was the daughter of a prominent diplomat who served as the Czech ambassador to Yugoslavia. Havel was the son of a wealthy real estate developer who owned the Lucerna Palace shopping complex. Following the communist coup in 1948, both families had their property confiscated by the state. Owing to his bourgeois background, Havel was branded a “class enemy” and could not pursue the education he wanted. He later spent time in prison as a political dissident. Albright would have likely faced the same fate had her family not fled to the US when the communists took over. (They had already fled the country once in 1939, before returning at the war’s end.)

Despite all this, Albright and Havel went on to achieve great success in their respective fields. Which illustrates an important point: you cannot destroy the elite. You can seize people’s property. You can round them up and put them in camps. You can even kill their family members. But sooner or later, they will regain their former status.

We already know that in the absence of purges, expropriations and mass killings, elite status is extremely persistent over time.

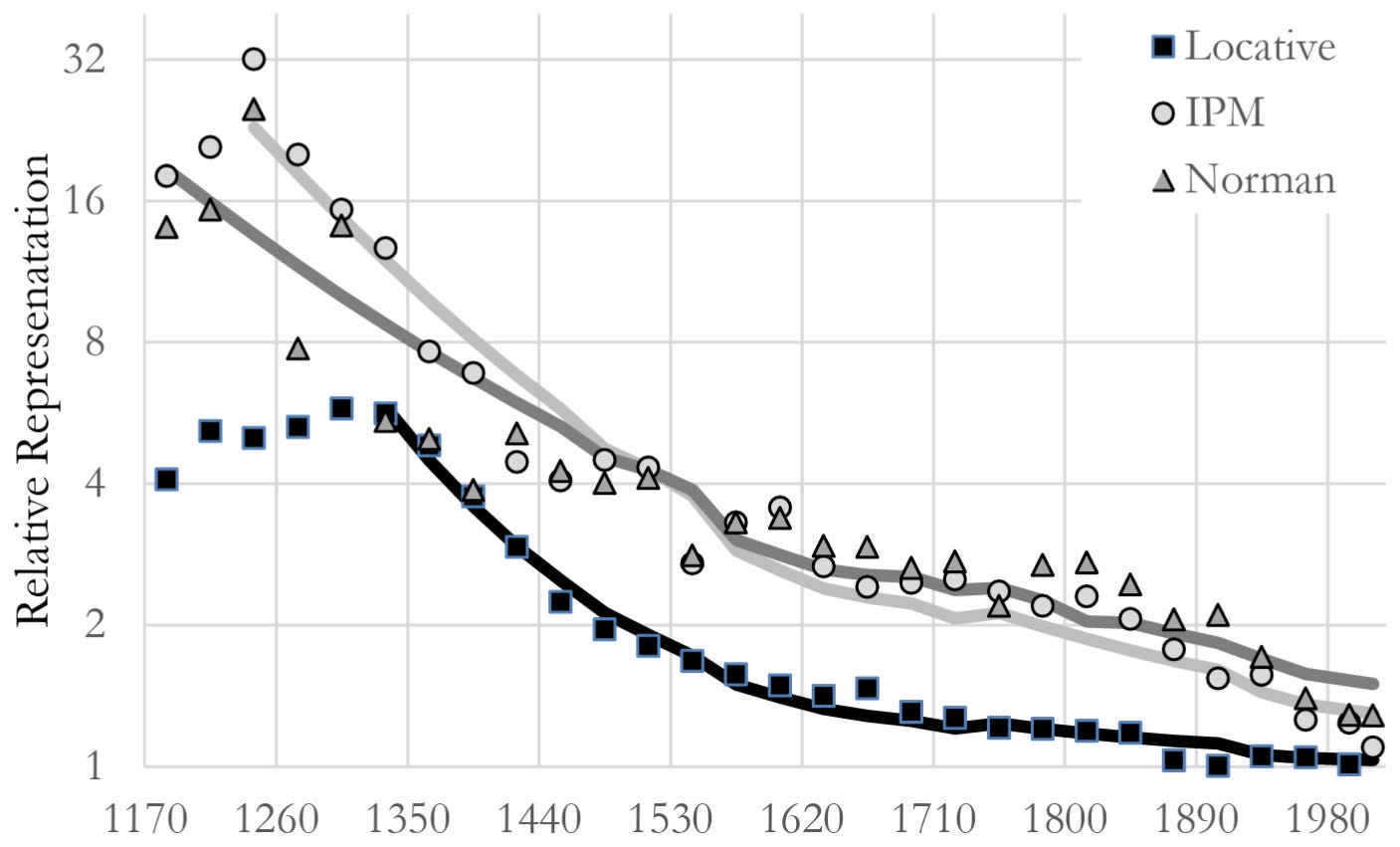

In a series of papers, Greg Clark has shown that the representation of elite surnames in various elite domains (such as lucrative professions or holders of great wealth) implies that long-run rates of mobility are low — much lower than traditionally assumed.1 He tracked surnames of wealthy landowners in England at the time of the Norman Conquest (such as Darcy and Baskerville) and found that they were substantially overrepresented among entrants to Oxford and Cambridge as late as the 1890s. Likewise, Guglielmo Barone and Sauro Mocetti linked current taxpayers in Florence to their ancestors with the same surnames in 1427. They too found very low rates of mobility: Florentine families that were wealthy in the 1500s were still richer-than-average six centuries later.

You might say it’s obvious that the descendants of Norman nobles and Florentine merchants would still be rich and powerful today. They inherited property from their parents, who inherited property from their parents, and so on, all the way back to the Norman Conquest and the Republic of Florence. It’s not that they are smarter or more hard-working than people with less impressive pedigrees, you might claim. It’s that they had a head start in life thanks to the wealth amassed by their great, great, great grandparents. The late Duke of Westminster (who became the second richest person in Britain) was once asked what advice he would give to young entrepreneurs, and his answer was: “Make sure they have an ancestor who was a very close friend of William the Conqueror”.

Yet even when elites lose their wealth and power at the hands of an authoritarian state, they or their descendants usually get it back. Which suggests that success isn’t just a matter of inheriting the family estate.

After defeating the nationalists in the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese Communist Party embarked upon one of the most far-reaching attempts to abolish the existing hierarchy in all of history. Every household was assigned a class label, and those designated “landlords”, “capitalists” or “rich peasants” had their land and assets confiscated by the state. Massive redistribution followed. By the mid 1950s, “poor peasants” owned more land per capita than “landlords”. Meanwhile, the share of output accounted for private firms dropped from 55% to essentially zero. The persecution of former elites continued during the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s. It became almost impossible for children from disfavoured classes to get a university education, and they faced intense stigma in the wider society.

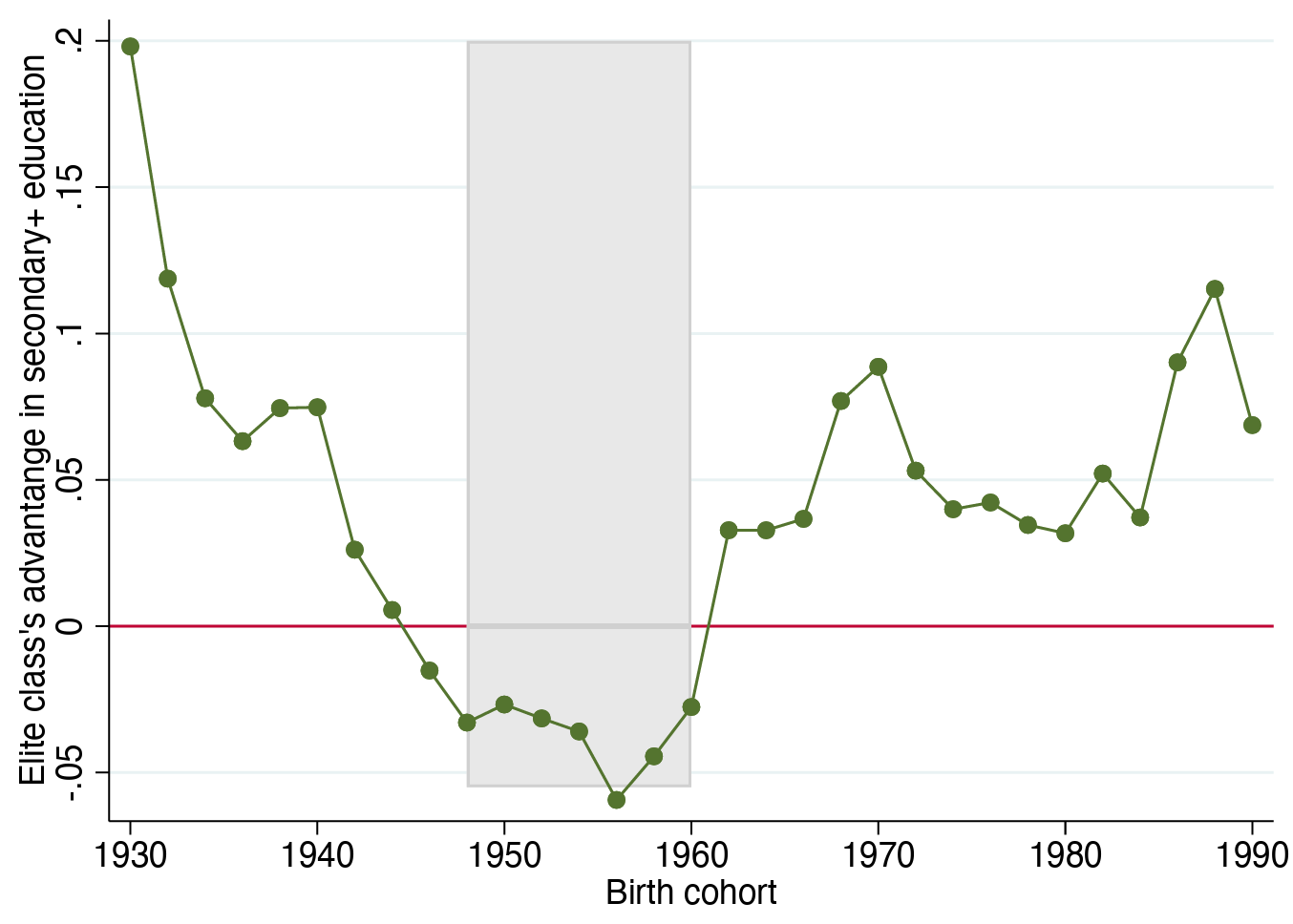

What impact did all these measures have? As Alberto Alesina and colleagues have shown, the generation most affected by them — the children of the people designated “landlords”, “capitalists” and “rich peasants” in the early 1950s — saw their social status plummet. Yet the next generation (i.e., the grandchildren) regained much of their lost status.

To demonstrate this, the authors analysed data from a large, nationally representative survey from 2010. The survey asked respondents the class label that their family had been assigned shortly after the Communist Revolution. And remarkably, the vast majority of respondents knew the answer — the labels having been passed down through the generations. (In some cases, individual respondents did not know but older members of their household did.) The authors defined the pre-revolution elite as respondents whose families had been designated “landlords”, “capitalists” or “rich peasants”. These individuals comprised about 8% of the sample.2

When the authors compared the incomes, occupations and educations of the pre-revolution elite and the masses in the generation most affected by the reforms, they found that they were similar. In other words, the pre-revolution elite had lost all its economic advantages. It was even slightly poorer than the rest of the population. But when the authors did the comparison in the next generation, which grew up after the return of meritocracy, they found that the pre-revolution elite had more education, better occupations and higher incomes.3

The pre-revolution elite’s status had been artificially suppressed in the communist era through a combination of expropriation, discrimination and stigma. Hence it re-emerged as soon as China began to embrace the market system (or “socialism with Chinese characteristics”, as they call it).

The Soviet Union took similar measures in its efforts to abolish the existing hierarchy. Under Lenin and then Stalin, these measures famously included the persecution of “enemies of the people” — aristocrats, land owners, businessmen, kulaks, bourgeois intellectuals and other suspected opponents of the regime. Such individuals were arrested (often based on nothing more than their social background) and then exiled to the Gulag, a system of forced labour camps spread across the Soviet Union. Here they were made to perform manual labour in the service of the state.4

When Khrushchev took over as First Secretary of the Communist Party in 1953, he pursued a policy of de-Stalinization (which had in fact already begun under Beria) that involved closing down the Gulag camps and releasing many of the prisoners. Yet for several reasons, a sizeable number of former inmates chose not to return to their prior places of residence and instead opted to make a life in the remote towns where they’d been imprisoned.

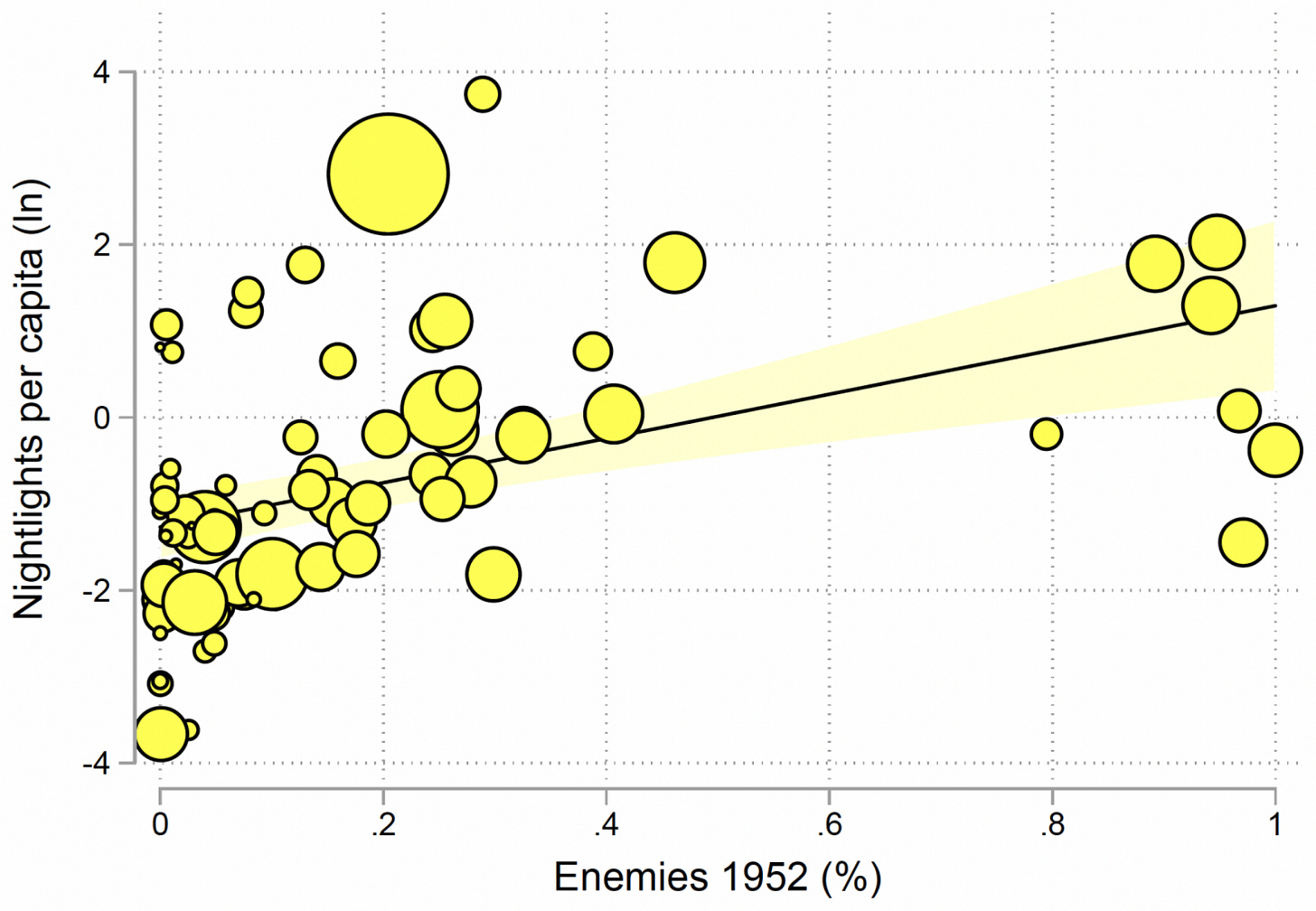

In a recent paper, Gerhard Toews and Pierre-Louis Vezina examined what impact the mass relocation of “enemies of the people” had on the towns where many of them settled. They obtained data on the number of “enemies”, as well as the total number of inmates, in almost 500 camps between 1921 and 1960. They then computed the share of inmates in each camp who were “enemies”, which serves as a proxy for the camp’s average human capital — since “enemies” were overwhelmingly selected from the wealthy, educated classes.

The authors found that this measure was positively associated with the population-adjusted nighttime luminosity within a 30km radius of former camps.5 In other words, the areas surrounding camps that had a higher share of “enemies” under Stalin are more economically developed today. To bolster their interpretation, the authors cite a famous Russian comedian, Ruslan Bely, who travelled all around the country during his career and said of Magadan (a small town in Siberia you’ve never heard of) that it had “a very well-mannered audience that laughs at the subtle jokes”. Bely attributed this refinement to the exiling of numerous members of the intelligentsia to Magadan under Stalin.6

Despite the fact that “enemies of the people” lost everything (including both their property and their reputation) as a result of the persecution, their children and grandchildren still managed to enhance the prosperity of the areas in which they found themselves.7

Although nothing as extreme as Mao’s Communist Revolution or Stalin’s Great Terror happened in the West, the US did follow a policy during WWII that would be unthinkable today, namely the mass internment of German, Italian and Japanese Americans. About 1,900 Italians, 11,500 Germans and 120,000 Japanese were incarcerated between 1942 and 1945. The camps to which they were sent were nothing like the Gulag; inmates were not forced to perform manual labour. However, they were deprived of their freedom and dignity, and many were coerced into selling their assets at steep discounts.

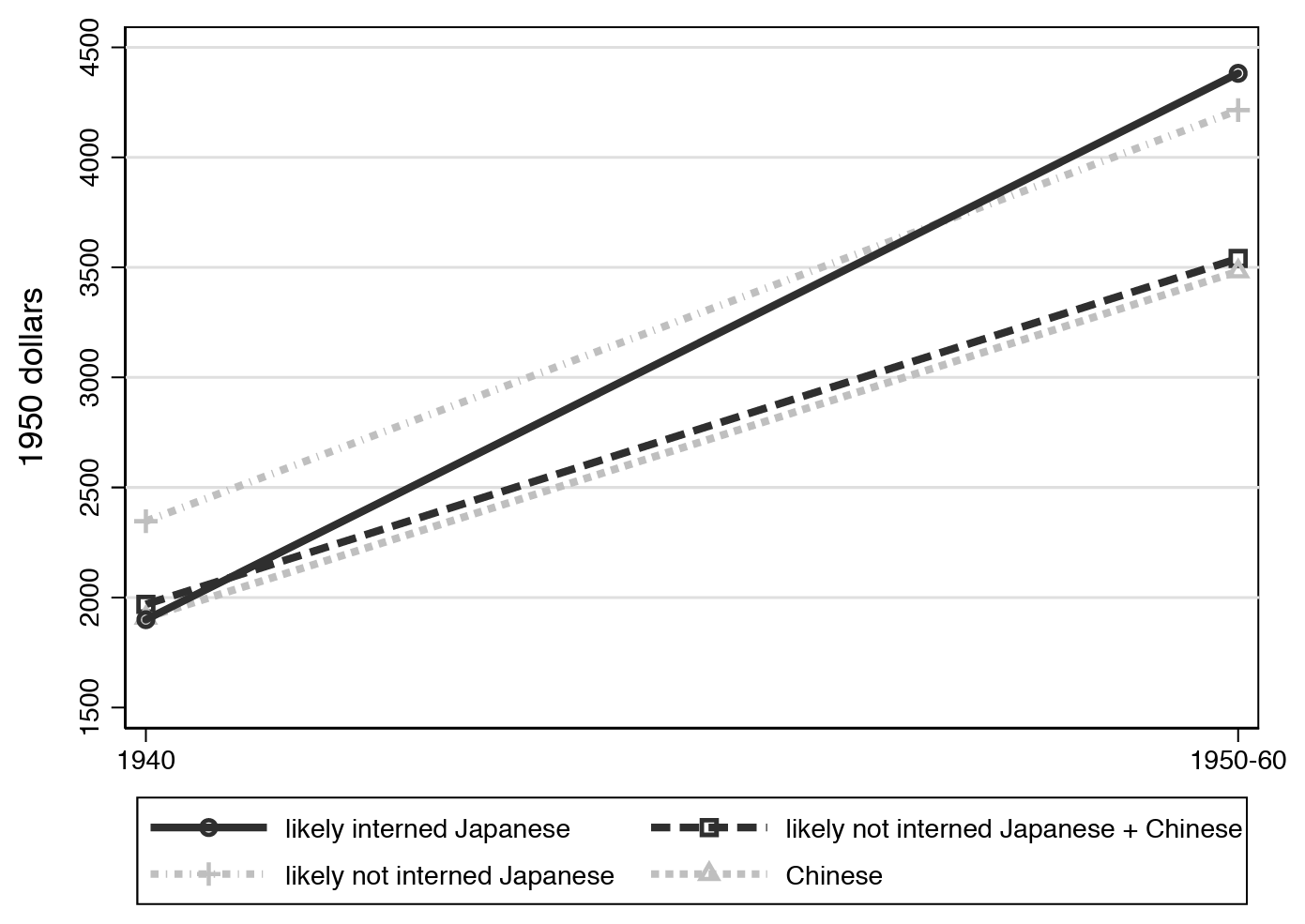

You might assume that all this would have hurt the inmates’ long-term prospects, particularly in the case of Japanese Americans, the vast majority of whom were completely innocent people who’d been in the country for a generation or more. Yet a study by Jaime Arellano-Bover found that the internment of Japanese Americans actually raised their long-term prospects.

Because there is no dataset containing information on the inmates’ incomes before and after they were interned, Arellano-Bover had to rely on other data sources to estimate the probability that specific Japanese Americans in the census (who could be tracked across the 1940, 1950 and 1960 waves) were interned during WWII. Specifically, he used camp records and a contemporaneous survey of Japanese Americans to estimate individuals’ probabilities of internment based on their state of residence in 1940 (before internment) and their state of residence in 1950 or 1960 (after internment). For example, almost no Japanese Americans living in Colorado before the war were interned, so individuals whose state of residence was given as “Colorado” in the 1940 census were assigned a very low probability.

Remarkably, Arellano-Bover found that Japanese Americans who were interned saw greater income growth between 1940 and 1950–1960 than those who weren’t. They also saw greater income growth than Chinese Americans, who were not subject to internment but faced similar levels of anti-Asian discrimination before the war.

In the paper, Arellano-Bover outlines some potential mechanisms that might explain this pattern. The key point is that there is absolutely no evidence that internment hurt the inmates’ long-term prospects. Which makes it rather unlikely that something as nebulous as “systemic racism” could be a major reason for racial gaps in American society today.

Why, then, is elite status so persistent over time? The obvious reason is genes. Even when persecuted and stripped of their property, elite individuals still pass on genes to their offspring — genes encoding traits like high intelligence, low time preference, conscientiousness, social skills and business savvy. And it’s these genes that explain the individuals’ original success as well as the subsequent success of their offspring.8

Intelligence appears to be a particularly resilient trait. Studies of holocaust survivors have found that they scored no worse on tests of cognitive functioning than their counterparts who were not affected by the holocaust. Likewise, a major study of the Dutch Hunger Winter found that individuals born during the famine did not score substantially lower on the Raven’s IQ test than those born just before or after.

Social inequality has been a constant throughout history, at least since the dawn of agriculture. Some people have more; others have less. It was not until the communist revolutions of the 20th century that states first attempted to impose real, material equality on all their citizens. Property was seized. People were rounded up and imprisoned. Many were executed or worked to death. And yet the elite could not be destroyed. Within a generation or two, they had returned.

Noah Carl is an Editor of Aporia.

Become a free or paid subscriber:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

In particular, the persistence of status from one generation to the next is on the order of r = .70 or maybe even r = .80.

These were individuals born between 1940 and 1965, who were aged 70–85 at the time of the survey.

These were individuals born between 1966 and 1990, who were aged 20–44 at the time of the survey.

“Enemies of the people” comprised about a third of all inmates.

Recall this image.

In addition, they found that share of “enemies” was also associated with the profitability of firms located within 30km of former camps as well as the wages those firms pay to their employees.

Another study found that the descendants of 18th century Hungarian nobles were still privileged in the second half of the 20th century, despite the communist takeover.

It is noteworthy that, with one exception, the papers cited in this article do not mention the word “genes”. The exception is the paper on China, which states in a footnote: “One could attribute part of the persistence and rebound to innate traits and characteristics, such as genetics, personalities broadly defined, intelligence, and emotional intelligence.” (This is a very strange phrasing: “genetics” and “intelligence” are not separate “innate traits”.)

Jesus famously said that the poor are with us always. Apparently the same is true of elites.

Nice one. One would expect the long-term persistence of eliteness to depend on assortative mating. Otherwise, many descendants of the elite should regress to the mean over generations.

Cremieux recently had a nice presentation on a related topic (social mobility) https://www.cremieux.xyz/p/intelligence-and-social-mobility