Why are black children 11 times more likely to be strip-searched?

James Thompson scrutinizes a questionable report on British policing...

Written by James Thompson.

The Guardian tells us that black children are being targeted by the police. After the bold headline above, they drive home the point:

The report released says 38% of children strip-searched were black. Black children make up 5.9% of the population, meaning they were six times over-represented. White children accounted for 42% of searches and make up 74% of the population.

So, racism? Police picking on blacks, going easy on whites. If this is not clear enough, they then tell us the relative frequencies:

The data was analysed for the Guardian by Dr Krisztián Pósch, a lecturer in crime science at University College London. It shows a black child in England and Wales was 11 times more likely to be strip-searched than their white counterparts.

The black rate of 6.44 divided by the white rate of 0.5675 = 11.35.

This, the newspaper says, quoting the Children’s Commissioner’s report, is:

[…] “deeply concerning” and “utterly unacceptable”, while the leader of black police officers said it was another example of institutional racism, which police leaders deny exists. Last week a report by Louise Casey found the Metropolitan police to be institutionally racist and riddled with discrimination that was “baked in.”

At first glance, anyone would agree. So, we proceed to the Children’s Commissioner’s report.

The report complains of poor data quality, in that the police often did not provide adequate data. This is a cause for concern and also a cause for caution in any interpretation of data, though the conclusions drawn by the Commissioner are very firm.

Even worse, the Report has not been able to lay its hands on proper national data on searches and arrests of children. As you will see below, this leads to a muddle, and it is hard to get an overall picture of the effectiveness of all searches, into which this specific category of strip searches (more intrusive) can then be placed.

Despite these shortcomings, the authors feel fully justified in giving a pictorial summary of what they consider to be the most salient results:

So, police picked on boys (95% of the time), who are only 50% of the population. That should be cause for concern, though the report does not make anything of it. Also not appreciated in the report, these searches were fantastically successful! One in every two found something which required further action. Few interventions are ever this successful. In terms of a medical intervention, treating two or three patients to improve one person's health (the case for most over-the-counter painkillers) is pretty good. Statins for the general population, for example, could be a Number Needed to Treat (NNT) of 60 to prevent a heart attack and 268 to prevent a stroke. Many people have to take the medicine to benefit one patient.

In this case, the police have achieved an NNT of 2. Brilliant, but not acknowledged in the report.

To place these 2,847 strip search cases (involving intimate parts of the body) in context, the report gives some national figures:

Police in England and Wales made 50,787 arrests of children in 2020-21, 62,449 in 2019-20, and 59,773 in 2018-19.

Police conducted 115,601 stop and searches of children in 2020-21 and 94,975 in 2021-22.

Police gave 5,258 cautions to children in 2021-22.

This is a jumble of different dates and events. Curiously, these figures are given but not commented on, so here is the little work I would have assumed the authors would have done. We can estimate that for 2020-2021 the 115,601 searches have led to 50,787 arrests, giving us an overall NNT of 2.3, which is very good. Stop and search is clearly worthwhile, but the report says nothing of the sort.

Incidentally, calling 16-year-olds ‘children’ can mislead. This report is mostly about teenagers, and mostly teenagers who are involved with drugs.

The report continues:

The vast majority (86%) of searches were conducted on suspicion of carrying drugs, followed by weapons, points and blades (9%) and stolen property (2%).

Figure 4 (see below) in the report shows the proportion of searches where the outcome was linked to the initial reason for conducting the stop and search. Here are the percentages:

In the 37% of cases where the outcome was linked to the initial reason for conducting the stop and search, the arrest rate was 22%.

In the 14% of cases where the outcome was “not linked to the initial reason”, (that is, they found something else illegal), the arrest rate was 6%.

In the 23% of cases where nothing was found, the arrest rate was 1% (possibly due to resistance while being searched).

So, if the police thought that someone was carrying something illegal there was a high success rate. Second, if they searched for one thing, they often found another illegal thing, with a lower but still worthwhile arrest rate. Finally, if they found nothing they usually arrested nobody, other than perhaps someone resisting search procedures. (The report is very taken by this 1% arrested, say it is of “particular interest” but do not discuss possible reasons).

Oddly, these percentages add up to only 74% of the sample. There must be some reason, but I can’t find it in the text.

Indeed, I cannot find any statistical work in the text. For example, (when searching an adolescent for drugs or weapons) was the detection rate any different in black and white adolescents? This is the key issue they have highlighted, but I cannot find this comparison in the report. If the police were really racist, their “hit rate” for black teenagers would have been even lower than for white teenagers.

They give lists of percentages, though they do not always add up, as in Figure 4. They do not even attempt simple Chi squares on race differences by “linkage” above, despite trumpeting about race differences in their report. See the footnote for an explanation of a Chi-squared test.1

They got their population race estimate from the 2021 Census, which is fine. Their few comments on statistical methods include the following:

A binomial regression was used to analyse the significance of the relationship between whether or not an Appropriate Adult could be confirmed as present during strip searches, and multiple predictor variables, including the gender of the child and geographic region.

Apparently, more adults were present in London searches, so that was the outcome of their regression equation, I assume. There are no statistical analyses shown.

The report shows a curiously incurious look at data. On the race issue, it compares sample percentages with population percentages, without considering that different groups may offend at different rates.

For example, why do the police apparently pick on boys? Very probably because boys are more likely to trade in drugs and carry weapons than girls. That is why a boy is 19 times more likely to be strip-searched than a girl. Factual considerations, not prejudgement.

Finally, the report does not give any data on the number of youngsters convicted of crimes and serving sentences in jail. Jail sentences eventually reveal previous cautions, often numerous. Only given such data could we judge if police were searching teenagers unfairly.

What data might the Commissioner have used in order to put strip searches into perspective?

Perhaps the government website on Ethnicity Facts and Figures can assist.

We can look at youth cautions over the last decade.

In the year ending March 2019, White children were given 6,065 cautions (83.1% of youth cautions)

800 cautions were given to Black children (11.0%)

In the 11 years to March 2019, the total number of youth cautions fell by 91%, from 93,656 to 8,552

There was a decrease in the number of youth cautions in every ethnic group

The percentage of cautions given to White children went down from 88.0% to 83.1%

The percentage given to Black children went up from 6.6% to 11.0%

For comparison, 81.7% of all children aged 10 to 17 years in England and Wales were White, and 4.4% were Black at the time of the 2011 Census

To summarise, cautions have fallen, except for black children. The latest data show that cautions for white children are very slightly above the population benchmark, and for black children they are 2.5 times higher. Overall, black children were 2.46 times more likely to be cautioned.

If cautions work, then subsequent arrests will be reduced. If there is no such effect, then cautions might simply be an indicator of continuing criminal behavior.

From the arrest data, it would appear that cautions don’t work, but on the contrary indicate that many of those cautioned continue to offend. Black boys are by far the most likely to be arrested. Few women are, but black women are the highest of this low range.

Arrest rates for both sexes per 1000 are White 9, Asian 11, and Black 29. Black youths are over 3.2 times more likely to be arrested. And when you compare black youths with the most numerous group, White British, they are, in fact, 3.63 times more likely to be arrested.

In terms of the range of subgroups per 1000: Chinese 3, Arab 3, White British 8, Mixed White/Black Caribbean 23, Black Caribbean 28, Black Other 61.

In that last group alone there were 17,008 arrests. If we want to do the relative risk calculation, Black Other are 20 times more criminal than the Chinese and 7.6 times more criminal than White British. Personally, I think it best just to give the rates.

In terms of overall arrests, whites account for 65.3% of arrests while being 82% of the population, and blacks account for 8.4% of arrests whilst being 4% of population. This suggests that in terms of finding people carrying drugs and weapons, police will be screening fewer whites than are found in the population, and 2.1 times as many blacks as are in the population. The police have sufficient knowledge to work out their own base rates. (Also, given their hit rate of one in two suspects, they will search two for every one they find).

So, teenagers are cautioned, and then some of those are arrested. Have they been cautioned beforehand?

From a 2017 report, we see:

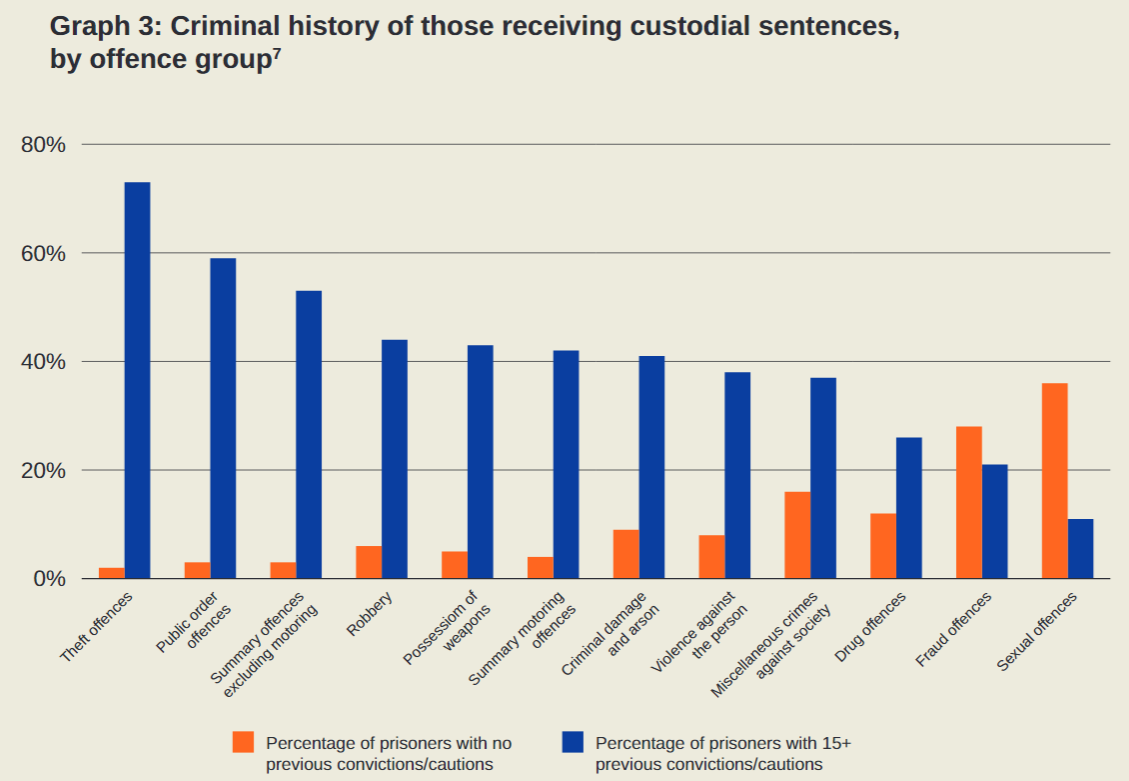

70% of prison sentences are imposed on those with at least seven prior convictions or cautions, and 59% had at least 11 previous convictions or cautions. Half of custodial sentences are imposed on those with at least 15 previous convictions or cautions.

So, if you get sent to jail, you are unlikely not to have been cautioned beforehand.

As shown below, drug offenses are one of the least likely to get you into prison unless you have many previous convictions, so black teenagers are rarely in prison just because of drugs.

Large percentages of prisoners have more than 15 previous cautions/convictions.

Let’s try another approach and look at young people after serving a prison sentence. By this stage, they should have learned the error of their ways, unless they are persistent criminals. Here are the findings:

There is a significant race difference in reoffending, particularly for young offenders, which would often lead to more stop and searches, and eventual re-conviction.

The Commissioner’s Report leaves out a lot. Apart from doing very little statistical inferential work, it leaves out the contextual data which is readily available on government websites.

Neither Commissioner nor journalists will even consider the hypothesis that some groups are more crime-prone than others. Despite the restrictions on the public reporting of the race of perpetrators, the public notices things, and so do the police.

The Commissioner for Children might have mentioned the previous Commissioner for the Metropolitan Police when, giving evidence to Parliament in July 2020, she said:

If I go to violent crime, in London last year 72% of homicide victims under 25 were black. Nationally—you probably know the figures—you are four times more likely to be a victim of homicide if you are black and eight times more likely to be a perpetrator.

To conclude, the police seem to be accurate detectors of those carrying drugs or weapons, bringing relief to other children, and probably saving a few of their lives.

James Thompson is a former senior lecturer in psychology at University College London. He taught at the University of London medical schools and has a Ph.D. in the cognitive effects of cortical lesions sustained in childhood. His interests are neuropsychology, psycholinguistics, child development, psychological trauma, intelligence and scholastic attainment. Read his Substack, Psychological Comments, here. Follow him on Twitter.

Chi-square is a statistical test used to examine the differences between categorical variables from a random sample in order to judge goodness of fit between expected and observed results.