Tariffs: A nuanced assessment

Free trade is generally good, but there's a role for strategic tariffs.

Written by Emil O. W. Kirkegaard.

Current Twitter debates about tariffs are quite one-sided. This is doubtless because Trump’s massive, haphazard tariffs came as a surprise to many and caused the markets to tank. The extent of the market loss changes by the day and sometimes by the hour because Trump remains erratic and other countries’ responses are unpredictable. Currently, the Dow Jones average is down to the level of August 2024. In a sense then, Trump undid about 7 months’ worth of market growth. Insofar as the normally pro-business Republicans like to brag to voters that they are great for the economy, this is an impressive own-goal.

On the other hand, America has deep, systemic economic problems, especially concerning debt.

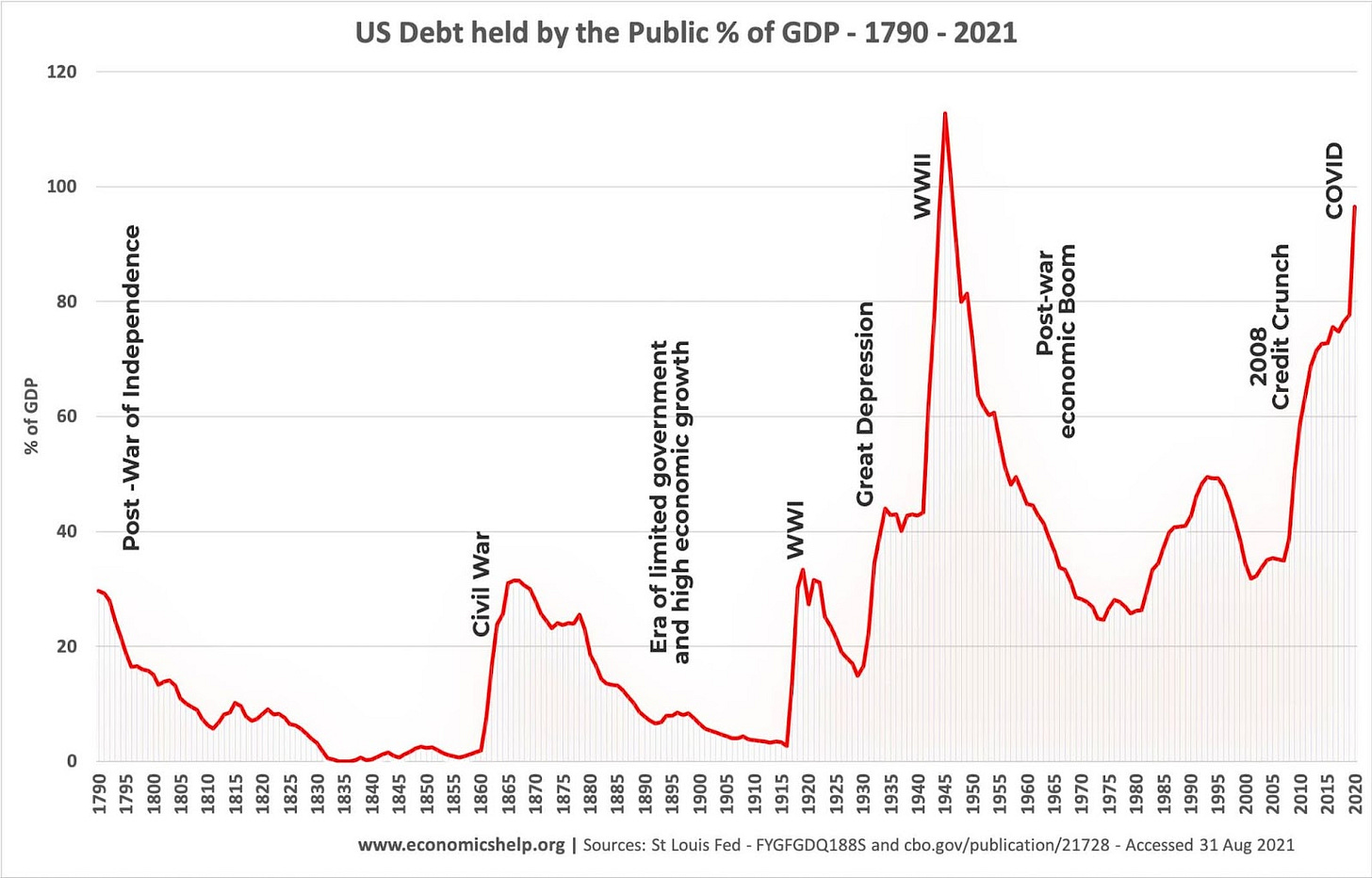

The current debt-to-GDP ratio is at its highest since World War II, and is higher than during the Great Depression, World War I and even the Civil War! This is an astonishing amount of debt and something must be done about it. Depending on how you count, the US has the eighth most debt relative to GDP in the world, only surpassed by countries such as Sudan, Greece and Japan. This debt has been growing rapidly since the 2008 crisis and the subsequent COVID crisis. Having debt means one must pay it back with interest. Among Western countries, the US spends the third largest amount of interest on its debt relative to GDP (3.9%), beaten only by Iceland (5.4%), Hungary (4.7%) and matched by war-time Ukraine. Interest on the debt is projected to account for 18% of the US government’s spending in 2025, about the same percentage as on its military.

Pick your least bad taxes

So how can the US government pay off its debt? Well, there are two ways: either make more money (taxation) or cut costs (reduce spending). Trump is frantically trying to do both. He has appointed Elon Musk to cut down on federal expenses through DOGE—presumably due to Musk’s success Twitter/X where he fired about 80% of the staff. Considering that Trump is against higher taxes (he lowered income taxes in 2018), how can he square the circle and increase tax revenues without raising taxes? Tariffs are largely invisible to the consumer, as they are not seen on price tags in supermarkets nor on people’s tax filings. This gives them something of a psychological advantage so far as visibility is concerned.

Interestingly, tariffs were the mainstay of government revenues for 1000s of years. This was also true for the US until quite recently.

As late as 1910, the US government earned about half of its revenue from tariffs. This changed with the introduction of the income tax in 1913 (which required altering the constitution), though there are many other taxes such as property taxes, corporate taxes, wealth taxes, sales taxes, land taxes and inheritance taxes. Another way to look at this is to examine the revenue from each type of tax:

The major increases are all related to wars (the Civil War in 1861-65, World War I in 1917-1918, World War II in 1941-1945) and the government’s size never shrank after each war ended.

From a strictly economic perspective, most taxes are bad as they disincentivize people from being productive in various ways. Though of course they allow the government to collect some that it promises to spend wisely on public goods such as roads or police. But not all taxes are created equal, so which taxes are least bad? Economists have spent decades studying this matter, and they have come up with various rankings:

The four studies included here agree that income and corporate taxes are the worst for economic growth. The reasoning for income tax, especially the progressive version of the income tax, is that it disincentivizes people from working more, and if it is progressive, it has a stronger effect on the most productive people.

Corporate taxes cause companies to move their registration to other countries (such as Ireland), depriving the country of all the money they would have paid. If companies end up moving jobs elsewhere, this will further depress economic growth. Perhaps for this reason, and because of the increasing mobility of industries and people, corporate taxes have been declining worldwide for decades, almost halving since 1980. (The OECD has formed a global tax cartel, with a mandatory minimum of 15%.)

The key lesson here is that taxes change behaviour since people obviously prefer not paying taxes if they can avoid them. Taxes that are easy to avoid are thus bad because they generate little revenue. Corporate taxes can also be avoided by intentionally not being profitable, and there are various other methods that creative and highly paid accountants have found.

At the other end of the scale are property taxes. Many types of property are unmovable (e.g. land, houses), meaning there is no way to avoid the tax and no point in trying. There may still be ways to game the system. If different types of land are taxed differently, property owners will of course try to get their land classified in the least taxed way.

Consumption taxes can be general (fixed added value tax on any sale) or imposed on specific categories of goods. For example, in Germany, the sales tax is 19% on most goods but only 7% on foodstuffs and 0% on certain speciality items (e.g., postage stamps). Excise taxes are basically the same thing but even more specific. They can be used to generate revenue, or to disincentivize consumption of certain goods (e.g., alcohol or tobacco).

These taxes can be avoided by importing the taxed goods from another country with lower prices, which means that these taxes are generally accompanied by customs inspections of such goods and legal limits on imports. For instance, Danes wanting to enjoy alcohol in Sweden, which has a very high vice tax and government monopoly on ‘strong’ alcoholic drinks, typically bring the alcohol with them. This means the police must inspect cars entering the country to check how much alcohol they have with them. Alternatively, people might opt to produce their own vice products, which because of poor quality control sometimes leads to mass poisonings.

The academic studies summarized in the table above did not include tariffs, and tariffs are not important contributors to revenue (they raise about 2% of total revenue in the US). So why go in that direction again? And why did governments move away from tariffs in the first place?

The core argument for free trade is outdated

The moral argument for trade is that trade by definition involves a voluntary transaction between two parties, where each of them gets something they want. If people in understand their own preferences, trade thus leads to everyone being better off than they were before.

Of course, people do not always act in their own best interests (a general problem for neoclassical economics). A gambling man may lose his family home and his car, leaving him unable to work or support his family. Many families have been torn part by alcoholism, even though alcoholics voluntarily traded their money for alcohol, which they desired more in the relevant moment. Generally speaking, however, trade is good.

David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage takes this further and notes that because of diversity in skills, geography and so on, some products are more efficient to produce in one place than in another. It is difficult to grow food in Norway or Canada because it is too cold, so it makes sense for those countries to produce other goods and then trade them for food (say, wheat from Ukraine or beef from Argentina). This allows different people and different countries to specialize in different industries, which leads to everybody being better off under global free trade.

Ricardo's theory remains the core argument for free trade (where everybody trades with everybody without tariffs), which is seen as an unalloyed good in mainstream discussion. But the theory dates to the early 1800s when the world was much less globalized. It states that if a country can produce something more valuable with the resources currently used for some product, it should import that product and produce the more valuable thing instead. However, the theory is problematic today because it rests on several dubious assumptions:

Trade is sustainable. Trade can be unsustainable when it is based on depleting resources. The tiny Polynesian island of Nauru was briefly one of the wealthiest countries in the world per capita, but it eventually ran out of phosphate to export and was left desolate afterwards.

No externalities. Prices often exclude negative externalities like pollution which may be local or global (e.g. oil spills, greenhouse or CFC gasses).

Factors of production move easily between industries. Workers and capital can't necessarily easily or quickly shift between industries. It may be better in the short term to trade, but if this means never developing your own industries, it can be a bad decision from a long-term perspective. Singapore used tariffs as protective measures to develop their own industries before reducing the tariffs later to compete fairly in the global market.

Trade doesn’t raise inequality. Trade may increase inequality even while growing the economy. Perhaps you are better off selling raw aluminum than processing it locally, but if all the wealth goes to a few billionaires or to foreign owned companies this may not be in the interests of the general population.

Capital isn’t internationally mobile. Today capital is highly mobile, and flows to where it has an absolute advantage, not a comparative advantage. Ricardo himself recognized this problem, noting that international capital immobility was required for his theory to work.

Short-term efficiency causes long-term growth. Optimizing current efficiency doesn't guarantee long-term growth. Countries can get trapped in economic "dead ends" by specializing in industries that offer no path to technological advancement, as happened with Portugal's wine industry.

Trade doesn’t induce boost productivity growth abroad. Trade can help other nations develop in ways that eliminate the original comparative advantage—as when Japan shifted from producing cheap goods to competing with American industries in sophisticated manufacturing).

While free trade can be optimal in the short term, it is not necessarily best for the country in the long-term. Points 3, 6 and 7 correspond to “infant industry” arguments. Proponents of free trade argue that if a country has the potential to be efficient in a particular industry then companies should be able to borrow in order to cover losses until they become efficient—sort of like Amazon making a loss for a decade before turning profitable. They also maintain that governments don’t have the incentive or knowledge to implement tariffs on the right industries. Additionally, some research suggests that subsidies are also more efficient for supporting infant industries than tariffs.1

Liegent

If you’re looking for more information on the topic but lack the time to read through a stack of books, check out our partner Liegent. They offer “shorts” that cover the key takeaways from books, which you can read or listen to in 20 minutes. Their library includes Ian Fletcher’s Free Trade Doesn’t Work—which outlines the problems with Ricardian theory, as well as other objections to free trade.

Other considerations

Aside from concerns about short versus long-term efficiency, there are other reasons a country might want to use tariffs.

When countries are hostile to each other, they often implement blockades (such as the allies blocking German shipping during the world wars). And during peace time, they may impose sanctions. Few economists complained about the decline of free trade when Western countries imposed unprecedented sanctions on Russia after the invasion Ukraine—even though these have harmed Europe far more than Trump’s tariffs are likely to harm the US.

Imagine a world in which a product is produced entirely in the most efficient country, say, beef in Argentina. If, for any reason, your country gets to be on hostile terms with Argentina (say because you had a small war with them), you would suddenly find yourself without any alternative beef production, or any local knowledge about how to produce it. Of course, beef production could probably quickly be increased elsewhere; other industries are more difficult to re-start.

The geopolitical conflict over Taiwan comes in large part from the fact that it produces the majority of the world’s advanced semiconductors. Countries like the US, which import these products from Taiwan but which are hostile to China, could be forced to defend Taiwan against China simply to ensure they don’t lose access to advanced semiconductors.

Similarly, if one or a few countries achieve global dominance in some industry, they may decide to form a price cartel and then dramatically raise prices (as happened in the 1970s energy crisis). If oil-importing countries had retained their own less efficient industries, they would have been far less vulnerable to such actions. Note that OPEC isn’t the only example of this (e.g., International Tin Council, the Coffee Cartel, Rubber).

What about trade deficits and unfair tariffs?

Trade deficits and “unfair tariffs” have been cited as reasons why Trump must negotiate tariffs with America’s trading partners. For instance, if you ask an AI to give a comparison table of US tariffs against countries and their tariffs against the US, you get a table like this:

There are indeed a number of countries that had higher tariffs against the US than the US had against them. For instance, Brazil and India impose approximately 10% tariff on US products, while the US only imposed 2% on their products. In these cases, one could make the argument that they ought to be equalized.

Similarly, Trump’s advisors point to trade imbalances and claimed that they are negative for the US. The table below shows the largest trading partners of the US and the trade balance for each:

One would have to look into the specifics for each to determine the reason, but it seems that the origin of the trade imbalances is that several of America’s trading partners (China, Mexico, Vietnam, Thailand, India and Malaysia) are selling cheap things Americans want to buy but aren’t rich enough to buy enough of the things Americans produce. Other countries call for different explanations. For Ireland, it is because many US companies moved there to avoid corporate taxes, so the US is essentially buying US products from itself but they count as Irish.

Imposing tariffs on Ireland would essentially mean that ex-US companies were taxed more heavily, meaning that American consumers would have to pay more for American-made products by companies with tax residence in Ireland. A wiser approach would be to lower the corporate tax, so that the companies moved back to the US.

In 2003, legendary investor Warren Buffett wrote a piece in Fortune to “deliver a dire warning” about growing US trade deficits.

He included a story to illustrate why trade deficits can be bad. In the story, the world is inhabited solely by the peoples of two islands, Squanderville and Thriftville. They have the same number of people and also produce the same product (food) at equal efficiency. Initially, they both work 8 hours a day, which is just enough to produce the food they need to survive. However, soon the people of Thriftville decide to start doing some saving and increase their work to 16 hours a day. The citizens of Squanderville are ecstatic about this and start importing food through loans and enjoying more leisure time. As time goes on, they have to start working more and more to cover the debt payments, eventually having to work more than 8 hours a day.

After this, Squanderville has a bright idea: cause hyperinflation in their currency to reduce the real value of the loans. Unfortunately, Thriftville has foreseen this move and has started buying up the property in Squanderville. In the end, the people of Squanderville have to sell off all of their assets and end up worse off than they were to begin with. This is because they had a trade deficit for food instead of producing their own. America’s ballooning national debt would suggest it has been heading in the direction of Squanderville.2

The take-away

The arguments made in this article should not be taken as a defense of Trump’s particular tariffs, which are rather extreme and have demonstrably roiled the markets. They are intended purely as an argument against what one might call free trade absolutism. Since this absolutism is currently enjoying a renaissance, likely as a reaction to Trump’s tariffs, it is worth taking apart.

Free trade is generally good because of its efficiency, which ultimately lowers prices for consumers and increases overall wealth. However, strategic tariffs can be wise. There are other options available to Trump if he’s looking to try something else.

Emil O. W. Kirkegaard is a social geneticist. You can follow his work on Twitter/X and Substack.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

There are also more modern arguments in favor of free trade, though these are less common.

While such simplified stories illustrate how trade deficits can be bad, they don’t really show that trade deficits are bad in themselves. It depends on the nature of the deficit and how imports are financed.

I'm glad you wrote this, because it's Trump and his policies are so haphazard, they tend to amplify voices on just one side of the debate

Trade policy is complicated.

I'm not sure that 78 year old Donald Trump is the guy to juggle all the balls intellectually.