Written by Alden Whitfeld.

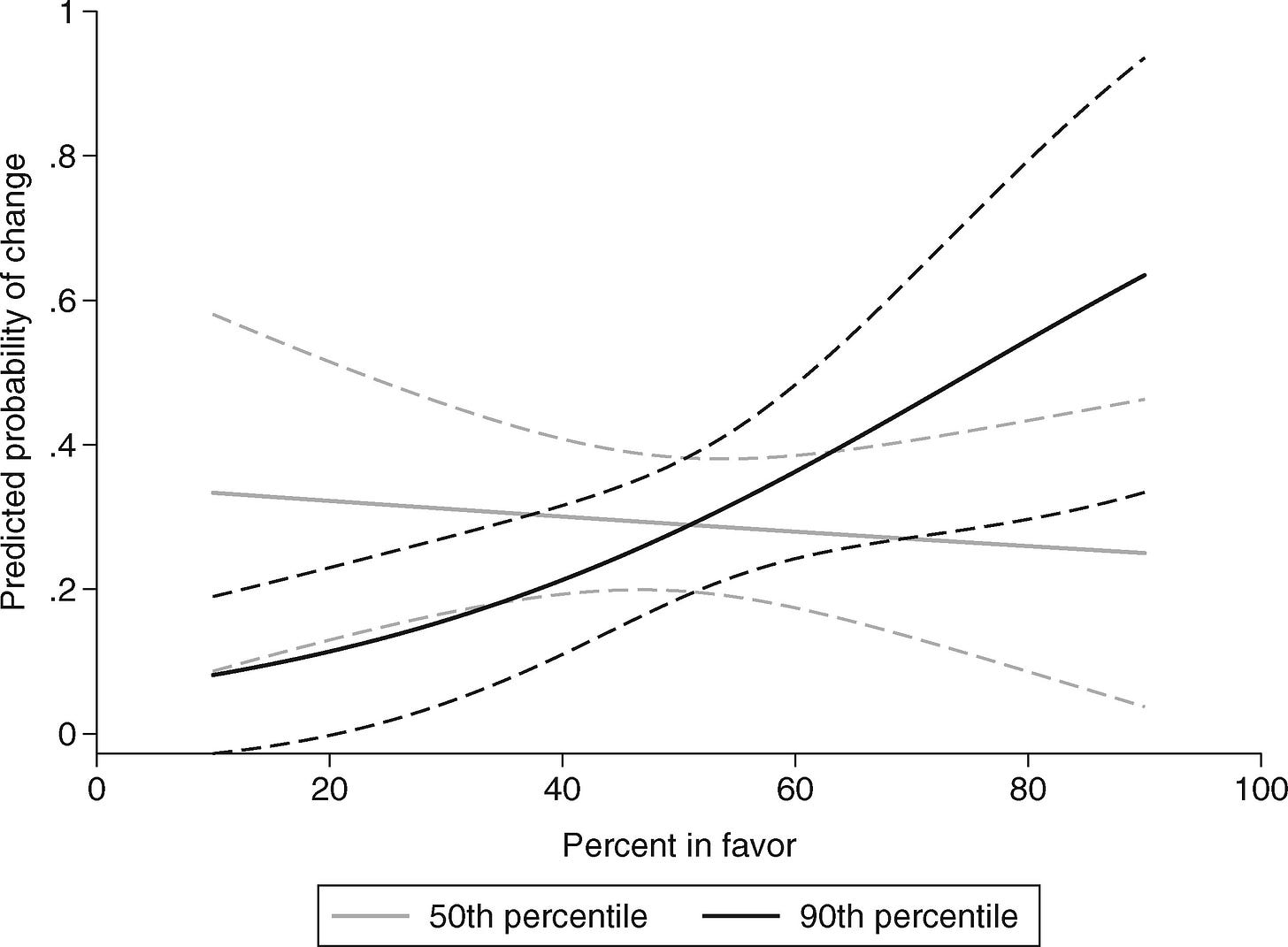

In 2014, Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page published a highly influential paper. Looking at 1,779 policy issues in the United States from 1981 to 2002, the authors examined how much impact the preferences of average citizens (50th percentile), affluent citizens (90th percentile) and interest groups had on policy change.

Initially, the preferences of all three groups had an impact. However, this was due to the fact that they were highly inter-correlated. The authors therefore compared the independent effects of each group’s preferences. What did they find? Average citizens were largely irrelevant, interest groups seemed to matter a bit, and affluent Americans had the vast majority of power.

The paper’s results are discussed in Gilens’ book Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America, which goes into much more detail on unequal policy responsiveness. One particularly interesting result discussed in the book is that policy responsiveness increases during presidential election years (see Table 6.2). Yet Gilens notes the following:

Most studies of federal policy making (including my own) neglect the durability of programs once adopted. However, an extensive dataset compiled by Christopher Berry, Barry Burden, and William Howell can be used to assess the durability of programs adopted in different years. Examining federal domestic programs adopted over a three-decade period, Berry, Burden, and Howell find that the funding for programs adopted during presidential election years was more likely to be cut over time compared to programs adopted during other years of the federal election cycle.

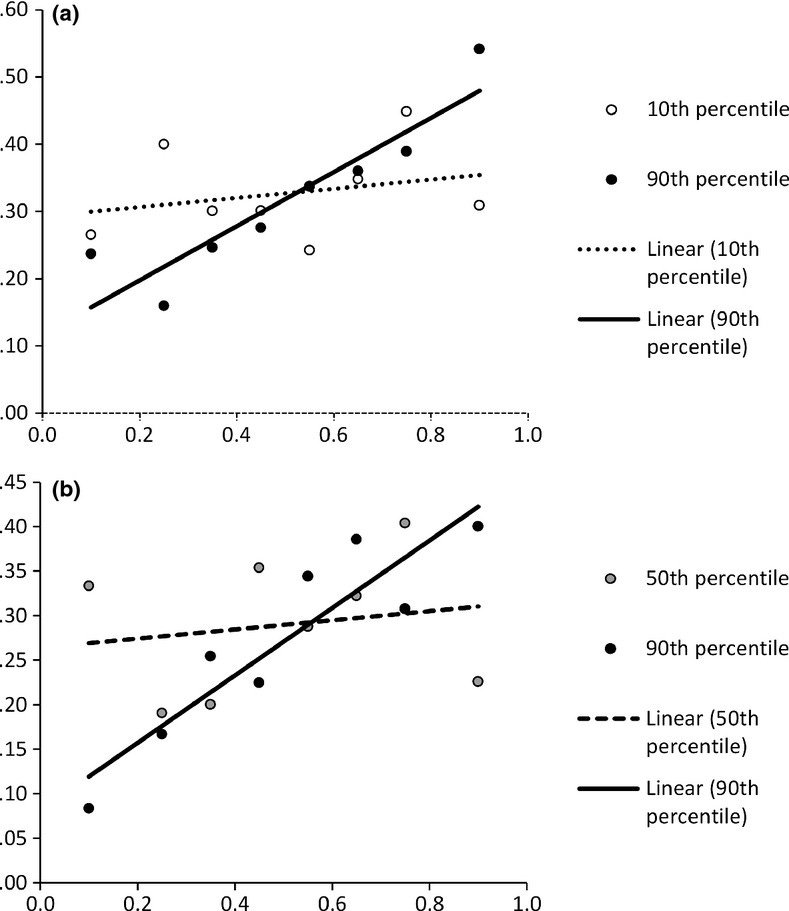

In other words, those policy victories the average citizen does manage to achieve are not guaranteed to last. Gilens did a follow-up study in 2015, which expanded the number of policies to 2,245, and the time span from 1964 to 2006, and which also considered the preferences of poor Americans (10th percentile). Once again, affluent Americans were dominant, while average and poor citizens had little influence.

When these findings were first published, they took the media by storm, receiving tons of attention and coverage. But they then got strangely memory-holed.

Unsurprisingly, various criticisms have been put forward. For instance, Omar Bashir argued that the high correlation between predictors might distort the results, and claimed using simulations that average Americans actually do hold about as much influence over policy outcomes as the affluent. However, Gilens addressed these criticisms in a response.1

Another criticism came from Alexander Branham and colleagues, who noted that in situations where average and affluent Americans disagreed, average Americans “won” 47% of the time. However, this is misleading. As Jarron Bowman explains, so-called win rates suffer from several issues:

Status quo bias. This is the common finding that the US government has a preference to change nothing, even when change is preferred by the population.

Defining thresholds and preference gaps. This was done differently by Gilens and his critics, and different definitions can result in substantially different findings.

Policies can change for reasons unrelated to who supports them. When a policy change occurs, this alone does not constitute a “win” on the part of the group that supported the change.

Bowman considers all of this in his paper, and what does he find? Basically the same thing as Gilens: average Americans have little influence, while affluent Americans have almost all the say. In his own words, his findings offer “strong evidence” for Gilens’ claims. So after all this back and forth, the best evidence we have suggests that Gilens was right all along.

What about outside of the United States? Europe is more progressive, the average citizens would matter more there, right? Apparently not. Wouter Schakel examined policy responsiveness in the Netherlands, and essentially replicated Gilens’ findings, as shown below. (His finding is not driven by differences in voter turnout.)

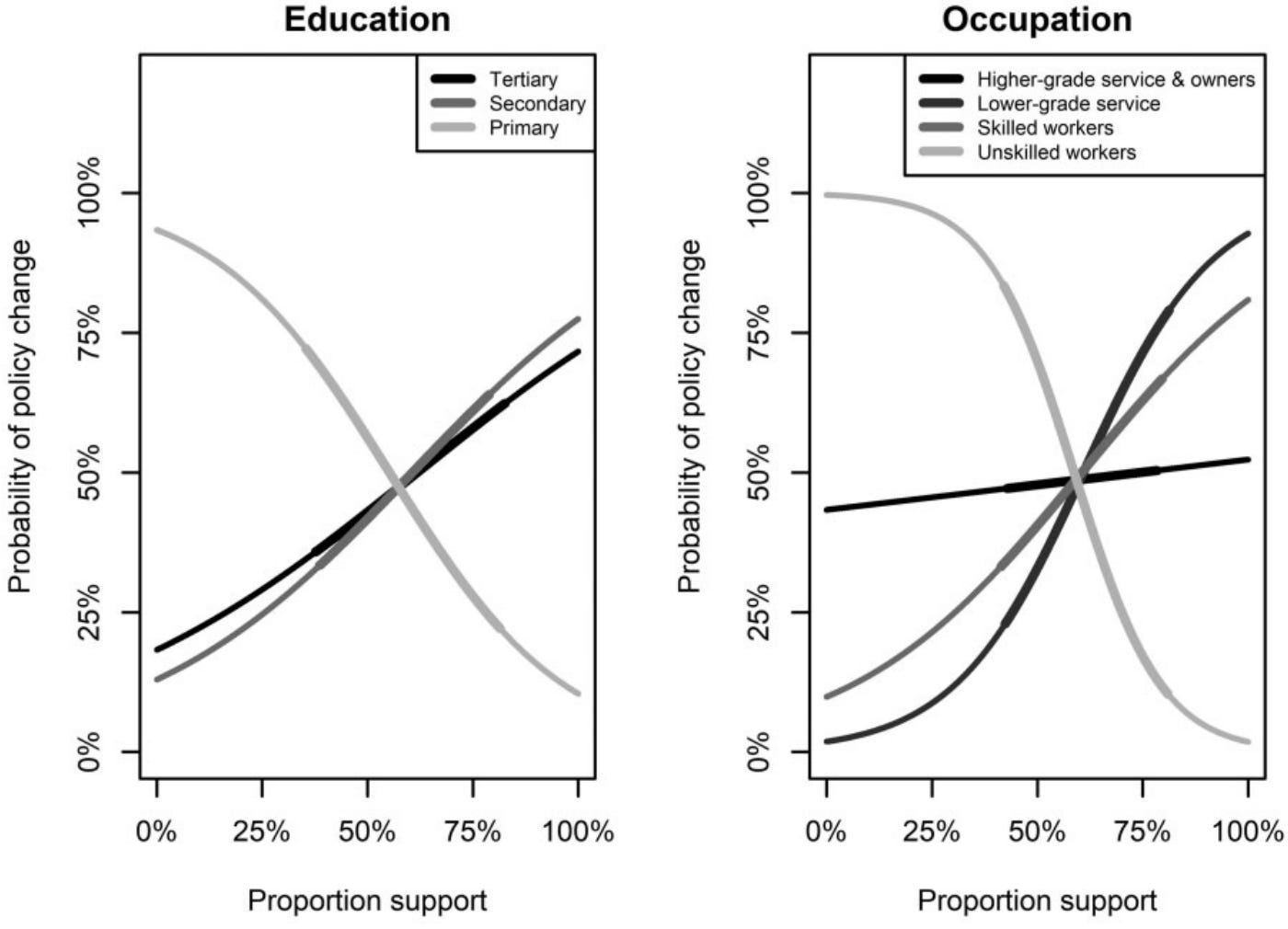

But income isn’t the only marker of elite status. Noam Lupu and Alejandro Castro studied unequal policy responsiveness in Spain using educational and occupational categories, and sure enough reached similar findings. As a matter of fact, their findings are even more damning. For the lowest status group in both categories, the effects were negative. So if poor citizens supported a policy, that policy was less likely to get adopted.

Comparing the results by policy type, the authors found that affluent Spaniards have the most influence on economic and cultural issues, their influence on security and foreign affairs being weaker. However, due to the small number of observations available for each analysis, only the result for cultural issues reached the conventional threshold for statistical significance. Though if I were to bet money on it, affluent Spaniards have disproportionate influence on economic issues as well, which would be consistent with what other researchers have found (e.g., Schakel et al., 2024).

Ruben Mathisen and colleagues were able to replicate Gilens’ findings in Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. This is somewhat surprising given that the Nordic countries are relatively more egalitarian. When looking at the cases where preferences diverged between the 90th percentile, 50th percentile and 10th percentile, across all the European countries, the 90th percentile was favoured over both the 50th and the 10th percentile.

What is interesting to note is that in the appendix of the paper, the net influence of those at the 10th percentile in Germany and Sweden seems to be negative. Norway is the most egalitarian in terms of policy responsiveness, but is still a far cry from the ideal of a government that cares about everyone equally. The authors themselves note that Norwegian governments are 2.5 times more responsive to the preferences of the 90th percentile than to those of the 50th percentile.2

What about good old Switzerland? The country that is often praised for being a bastion of direct democracy must surely be an exception? It turns out, not entirely. As Manuel Wagner found, once you account for the fact that preferences between various groups are correlated, the effect of the 90th percentile gets stronger, while the effects of the 10th and 50th percentiles disappear. And the same holds true for different education levels in Switzerland.

One caveat is that when it comes to policy issues addressed by popular initiatives, the results are much more egalitarian. In fact, it would appear that the 90th percentile actually has the least influence. So Switzerland has something going for it, though only in respect of popular initiatives.

Regardless of your opinion on the modern idealization of liberal democracy, the reality is that it barely exists outside our own imagination. To the extent that average citizens get anything they want, this is mostly just a coincidence driven by the fact that they often agree with affluent citizens about policy.

Of course, elitism isn’t inherently bad. In most democracies, voting itself is already selected. Non-voters in the US tend to be younger and tend to have less education, lower income, weaker political affiliations, and less trust in the system (Pew Research Center, 2014; Thomson-DeVeaux et al., 2020). It is debatable whether encouraging greater turnout from this group would be a net positive.3 Selection, on its own, will bias outcomes away from being perfectly representative.

The same is true in Switzerland, which is exceptional in another way: low voter turnout. Who votes and who doesn’t vote in Swiss national elections? André Blais found that compared to Germans, the Swiss are less likely to vote if they perceive government and politics as complicated, providing clear evidence of selection.

There is also evidence that granting women suffrage led to increased welfare spending across Western countries (Kirkegaard, 2019). This should not be surprising at all: when the composition of a democracy changes, we’d expect policy to change too. However, since we know “the people” don’t really matter, what really happened in the West is a gradual change in the composition of elites (Roine & Boschini, 2020).

Since women and minorities generally score worse than men and whites on tests of political and scientific knowledge (Lynn, 2001; Pew Research Center, 2019), it doesn’t take a genius to figure out how their increased influence has shaped Western society. A naïve optimist might believe that differences in political knowledge can simply be fixed by promoting education. While it’s certainly true that education and political knowledge are positively correlated, the relationship is mostly due to familial confounding rather than an effect of education itself. This is supported in a study by Aaron Weinschenk and colleagues, which utilized identical twin pairs in a fixed-effect model and found no evidence that more education increases political knowledge.

Let’s consider the issue of voter rationality for a moment. By rationality, I mean whether voters base their choices on what they expect to be the best possible outcome given the available information, and not on external biasing influences. Importantly, this assumption does not hold.4

By extension, this means that democracies do not display “wisdom of the crowd”. Indeed, this is the argument that Bryan Caplan makes in his book The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why Democracies Choose Bad Policies.

Wisdom of the crowd works when the error from individual inputs is random, such as when a crowd of people are asked to guess the weight of a bull. However, voters’ preferences are not like random errors. They are more like systematic errors that disproportionately go in one direction, causing the average of their preferences to deviate from the optimal policy. Caplan demonstrates this by comparing the public to the “enlightened public” (a hypothetical group of people with entirely average circumstances but with the same level of knowledge as an economist) and to economists. He finds that the former group disagrees substantially with the two latter groups.

But hang on, doesn’t this conflict with all the literature purporting to show that democracy is good for economic growth? Well, yes, and the reason is simply that the relevant literature is wrong.

Marco Colagrossi and colleagues meta-analyzed 188 studies on the relationship between democratization and economic growth, and found a positive correlation between the two. The problem (aside from the value being only 0.04) is that the correlation disappeared once human capital was controlled for.

A highly influential paper by Daron Acemoglu and colleagues found that democratization increases GDP growth by a whopping 20% over two and a half decades. If your intuition says this sounds too good to be true, that’s because it is. What’s going on? The answer is that the authors’ models counted recovery from economic crises as “growth”, which is obviously problematic given that countries recover from crises at much faster rates than they actually grow. A retrospective study by Julia Pozeulo and colleagues vindicates this. When democratic transitions that occurred after economic downturns were excluded, there was no evidence of positive effect of democratization. More recently, Ziho Park found that the association between democracy and economic growth is due to the fact that Western countries favour democratic regimes and impose sanctions on non-democratic regimes. As the author notes:

I revisit Acemoglu et al. (2019) and find support for the democratic favor channel. That is, I analyze the country panel data and regress GDP per capita on democracy and lags of GDP per capita. I show that, once I control for being targeted by sanctions from the West or the United Nations, most of their results turn insignificant or negatively significant.

So when done properly, the research indicates that democracy’s effect on growth is either nonexistent or even negative. It’s easy to make democracy look good for the economy when: democratic countries are mostly Western nations with high IQs and high rates of innovation; and you punish the countries that disagree and don’t adopt your system.

There is also the moral argument that democracy is a human right. Yet Jason Brennan, author of Against Democracy, has a rather different conclusion.

He presents a hypothetical capital punishment case involving a defendant and five jurors, where each juror possesses a trait that makes him unfit to serve. The first one outright ignores the evidence; the second one is irrational and evaluates the evidence in a clearly biased way; the third one is impaired and does not understand the case being presented; the fourth one is immoral and decides the defendant is guilty because of some irrelevant characteristic; and the fifth one is corrupt and gets bribed. Is this jury’s verdict legitimate?

American law says no, and in fact there are various mechanisms that allow for such cases to be appealed or overturned. But in a democracy, where elections impact the lives of everyone, suddenly we have to just go along with them and accept their outcomes, including those that we didn’t support. Unlike in the case of other “rights”, voting allows you to impose your will on others. It is far from obvious that preventing bad inputs from harming innocent people is immoral.

Democracy, as most people conceive of it today, is a system that does not exist in practice and is not inherently desirable even if it did exist. This is not to say that authoritarian regimes are automatically better. After all, there are a remarkable variety of such regimes, and they too have produced plenty of failures. Getting the right authoritarian leader can be beneficial, but getting the wrong one can be disastrous.

The real problem is not elitism per se. it’s the fact that elites are delusional and out of touch with reality. People are only starting to express discontent with the state of “democracy” because the gap between elite and average interests is becoming increasingly apparent. In Charles Murray’s book Coming Apart: The State of White America, he presents evidence of a growing divergence since the 1960s. Affluent Americans are increasingly unlikely to ever interact with ordinary Americans, preferring to live in their own gated communities, ignorant of the world around them. All the while, ordinary Americans have seen their situation deteriorating.

It will be interesting to see what happens once elites and average citizens are so far apart in their preferences that even coincidental “victories” for average citizens become a rare occurrence.

Alden Whitfeld is an independent writer who does research on immigration and politics. He is co-owner of the blog Heretical Insights and can be found on Twitter.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

Specifically, he pointed out that Bashir was mistaken about multicollinearity (citing an excerpt from a manual for regression analysis) and that Bashir had done the simulations incorrectly.

The authors also found that, prior to 1998, left-wing governments were more responsive to the preferences of poor and middle income citizens on economic and welfare policies. However, this was not true after 1998.

Note that moderates show less stability in their beliefs over time since they’re less certain about their worldview (Zwicker et al., 2020). They are also less likely to be politically engaged than radicals (Pew Research Center, 2021). Moderates seem to “go with the flow”, and are more likely to uphold the status quo regardless of whether it is optimal. This might explain why, news outlets classified as center-leaning actually show a left-wing bias in terms of how frequently they use terms denoting political extremism (Rozado & Kaufmann, 2022).

Interesting article.

I think the key passage is “ Getting the right authoritarian leader can be beneficial, but getting the wrong one can be disastrous.”

Democratic governance is not about implementing the popular will or picking the best leader. It is about ensuring a peaceful transition away from bad leaders. Authoritarian leaders are very hard to get rid of without violence, and that violence can easily turn to civil wars that tear apart societies.

Democratic governance may be the second worst form of government, but the worst form of government is all the others.

Congratulations Alden 🎉