Surrogacy: Looking for harm

Cremieux Recueil reviews the scientific literature on surrogacy

Written by Cremieux Recueil.

TL;DR: Cremieux Recueil reviews the scientific literature on surrogacy. He concludes that there is little evidence of physical or psychological harm to the surrogate mother, the surrogate child or the intended parents. However, the possible exploitation of surrogate mothers is something that has to be kept in mind.

Surrogate mothers are women who become pregnant and give birth to a child that is intended for someone else. They are the subject of immense controversy and derision – from both the religious right and the progressive left. Detractors on the right view surrogacy as immoral, emphasizing the need for parental bonding with infants, and thus opposing the separation of kids from their biological parents. Detractors on the left view the practice as exploitative and sometimes even as tantamount to eugenics.

But political narratives aren’t satisfying. If any side is right, it won’t be in virtue of their stories and opinions alone. Knowing more about surrogacy may help to correct these narratives, so let’s review the facts. To start things off, just how common is it?

Prevalence

Surrogate births are uncommon. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that, between 1999 and 2013, 2% of U.S. pregnancies using assisted reproductive technology (ART) involved surrogates. That 2% corresponds to a total of 30,927 instances of surrogacy over a fifteen-year period and an increase from about 1% of ART pregnancies to around 2.5%. The result in terms of births was considerably smaller: over that period, there were 13,380 deliveries of 18,400 infants (with 53.4% of surrogate deliveries involving twins, triplets, or beyond). For comparison, the CDC reported a total of 3.93 million births in the U.S. in 2013 alone. In other words, fifteen years of surrogate births amounted to less than half a percent of the births in a single year of that monitoring period.1

The discussion about surrogacy has become more heated precisely because use of the practice has undergone rapid and recent growth. Global Market Insights projected that the market for surrogacy would grow by more than an order of magnitude between 2018 and 2032. For a market worth $14 billion in 2022, that amounts to a sizable $129 billion by 2032.

But the size of the market doesn’t directly inform us about the number of surrogate births. The CDC’s most recent numbers come from their 2020 report on ARTs.2

Between 2013 and 2019, the proportion of ART pregnancies with embryo transfers that involved a surrogate increased from 2.6 to 5.4% before dipping to 4.7% in 2020, presumably due to the COVID pandemic. The report itself does not indicate how many surrogate births took place, only how many ART pregnancies involved surrogates. Using the numbers for the period 1999-2013, there were 30,927 ART pregnancies that involved surrogates, so only 43.26% resulted in a birth. That’s a high success rate. To put that figure into perspective, compare it to the percentage of ART uses that result in live births in general.

Between 2013 and 2020, there was an 11% increase in the percentage of assisted births that resulted in a live birth. From the numbers provided in the report, it’s not clear why this happened, but there are two main possibilities – both of which may be true to some extent. First, technology may have improved, so if the people who used ARTs in 2013 teleported to 2022, they would be more successful. For example, the transition from the slow freezing of eggs to vitrification substantially improved the use of egg freezing services. Another source of improvement is the increasing use of donor eggs, which is a major reason why gains have been greater at older ages.

Second, there may have been a compositional shift whereby, as ARTs became more widely used, the population changed in ways that led to higher success rates. For example, as in vitro fertilization (IVF) became more common, the people who use it may have become those who have fewer or more marginal fertility problems compared to earlier cohorts of users. Regardless of the reasons, surrogates are more likely to successfully deliver a child than typical users of ARTs, perhaps because they tend to be younger, perhaps because they tend to be healthier, or likely some combination of the two.

To bound the number of surrogate pregnancies, let’s assume that success rates vary between the average for all ART users in 2019 and 100% success even though we know the success rate is higher than it is for typical ART users. The report’s description for Figure 8 reads “the number of embryo transfer cycles that used a gestational carrier increased, from 2,841 in 2011 to 9,195 in 2019, with a decrease in 2020 (7,786)” (p. 21). With 37.2% success, that’s 3,421 infants born via surrogacy.

Consider three facts. First, surrogacy is expensive. Second, most people prefer not to use surrogates, and even many infertile women have negative opinions towards surrogacy. And third, many wealthy countries have banned or severely restricted surrogacy. The result is that globally, surrogacy is responsible for a small fraction of the births in the U.S. alone. In other words, it is very rare.

Why do people seek surrogacy in the first place?

Indications for Surrogacy

While precise and current numbers aren’t available, the most common reason people seek out surrogates has been and remains fertility problems. Women suffering from Müllerian aplasia, Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome, and other fertility-limiting conditions are still the primary users of surrogacy services. The simple fact is that obstetric conditions often affect the people most likely to want kids: young women. These women then look for other means of having kids, despite conditions like ovarian cancer, structural abnormalities, repeated miscarriages or demises, hormonal problems aplenty, endometrial issues, etc.

Another, fast-growing group of surrogacy seekers is homosexuals. Since the legalization of gay marriage, many gay couples have gotten married and decided it’s their time to have kids. As such, they’ve been greatly increasing the demand for surrogates. This is primarily a male thing. Lesbian couples tend to seek out sperm donors (though they still seek surrogacy arrangements at greater rates than heterosexual couples).

Homosexual parents were relatively rare until quite recently, and many have expressed concerns over their ability to raise children. A review of the papers on this topic was inconclusive about whether having homosexual parents affects kids’ outcomes. The only outcome noticeably affected by having homosexual parents seems to be kids’ own sexuality – perhaps because homosexual parents are more accepting of non-heterosexual sexual orientations among their own children. Because the research on this topic is of unusually low-quality, due to issues of low power and unrepresentative comparisons, it’s probably not informative. Yet insofar as behavior genetic studies tend to show near-zero family influence on most of the traits people find important, unless homosexual families offer a substantially different environment, it’s unlikely that they affect child development.

Can the women who have fertility issues even afford surrogacy? How well compensated are the surrogates?

What’s the Price?

If you search for estimates of surrogacy prices, the results will end up fairly similar: $110,000 to $170,000, $110,000 to $225,000, as little as $15,000, an average of $100,000, and up to $250,000, around $80,000 to upwards of $200,000, $125,000 to $175,000, as little as $13,000 to $220,000 – you get the picture. Surrogacy in the U.S. is a costly endeavor, with average costs per child running over $100,000 total. If IVF is involved, expect to pay about $20,000 on top of that. That’s the price people are willing to pay to have a child.

Of course, not all that money is handed over to the surrogate mother. A sizable chunk of it goes towards agency and legal fees, fertility treatments, donor egg and sperm costs, etc. Many of these costs are situation-dependent, but if you’re spending $100,000, expect to pay roughly 60% of that to the surrogate herself. If they’re an experienced surrogate, and thus the risk of a miscarriage or other mishap is lower, then expect to pay closer to $80,000.

With all these costs, it’s obvious that surrogacy is inaccessible to most people. Although people struggling with fertility tend to be older, and therefore tend to have higher earnings, wage trajectories aren’t so steep that lots of older people can afford to pay $100,000 for something that’s also very time-consuming.

But there’s a simple way to drastically reduce the costs: use an international surrogate. The U.S. has the world’s highest wages for a major nation. Hiring a surrogate elsewhere means the costs will be scaled relative to that nation’s wages, which will almost certainly be lower than they are in the U.S. For example, one estimate for the cost of surrogacy without IVF in the U.S. was $120,000, but in the same table, the cost for hiring a surrogate in Ukraine was a much more reasonable $45,000, and that’s all-inclusive.

The fact that surrogate wages are so modest, despite the length of time and the emotional toll involved, has led many people to describe the transaction as exploitative. When the transaction extends across borders, where the economic gap between surrogate and intended parents is much larger and the law is much murkier, the case for considering surrogacy to be an economically exploitative act is greatly strengthened. The logic is simple: few can resist several years’ worth of wages.

I mentioned international surrogacy is an area where the law is murky. This is especially true when the people seeking an international surrogate come from a country where surrogacy is illegal. For example, Germans going to India for surrogate services will have to subject their surrogates to legal travails related to the child’s immigration status. But perhaps most damaging of all is the possibility that they abandon the surrogate entirely, leaving her without any recourse and saddling her with a child, abortion, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy or worse.

The price of surrogacy is high, the service is not available to all those who want it, and if it were, it would presumably entail something like slavery – and in certain very rare illegal situations, it actually does. Resolving the issue of whether surrogacy is exploitative is beyond the scope of this post, but it is still worth asking: What sort of woman becomes a surrogate?

Who are Surrogate Mothers?

Surrogates are often sisters, mothers, friends, or extended family members. Since the surrogacy involves relatives, this can make it appear like incest is involved – but it isn’t, because donor eggs are typically used. On the other hand, when surrogacy is compensated rather than altruistic, the surrogate is virtually always a stranger.

The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine both recommend that the woman be 21-45 years of age, in good physical condition, and have had at least one previous pregnancy that was carried to term without complications. If the woman has had more than five previous deliveries or three with Cesareans, being a surrogate is not recommended. Psychological consultations are also advised, since a woman who may endanger the life of an unborn child is unfit to be a surrogate.

Since there are many ways for couples to find and contract their surrogates, and it is imperative that they respect her autonomy, the specific details of finding and dealing with surrogates can be thorny. Nevertheless, some generalizations can be made. For example, surrogates in the Western world are often family members and decently well-off, while in the developing world, they tend to be relatively well-off for where they are.

Why well-off women would want to engage in this is practice is, of course, a personal matter and one that’s likely to be highly situationally dependent. Perhaps surrogates underestimate the potential harms of surrogacy. In fact, what is the harm in it?

Analyzing Harms

Aside from legal, financial, and social harms, obstetric complications represent one of the most serious potential harms to surrogate mothers – for the same reasons that they represent one of the most pressing sources of potential harm to non-surrogate mothers. After all, such complications are among the most common negative outcomes for pregnancies in general.

There are few studies on this topic, but two of them, one covering an international sample and the other from Canada, indicated little unique reason for concern with surrogacies. In Parkinson et al.’s international study, the main risk factor for complications was multiple birth (twins, triplets, etc.) but the risks associated with surrogacy were not exceptional when compared to IVF in general. In Dar et al.’s study of Canadians, maternal complication rates and fetal anomalies were roughly as prevalent as in comparable populations. There doesn’t seem to be much that’s unusual about pregnancy or obstetric outcomes for surrogates as compared to typical successful users of IVF.

But what about harm to the child?

Gestational Age

Preterm birth is considered a risk factor in many bad outcomes for kids. Unsurprisingly given the prevalence of multiple births, it is also extremely common in IVF and surrogacy generally – just how common is easy to see:

But the potential for early gestational age is not a reason for concern, since again, if the comparison group is IVF users, surrogates do just fine.

Birthweight

Another risk factor for everything under the sun is low birthweight (LBW). The plot above shows that low birthweight is very common in multiple births, but for singletons it’s not very common among ART babies.

These European case studies found LBW rates of 0-11.1% for surrogate singletons, 13.6-14% for IVF singletons, and 14% for those delivered without surrogates or IVF. In the chart above, the rate was 7.6% with ARTs, and that’s more recent, so things may have improved or selection into IVF use may have changed. Regardless, the differences were minuscule.

But what about twins? One cohort gave a LBW rate of half for surrogate’s twins, 56% for IVF user’s twin birth, and 53.6% for donor egg twin births. In another cohort, the mean surrogate twin weight was 2.7 kg versus 2.4 kg for the mean IVF twin.

As with gestational age, any concerns that apply to IVF apply to surrogacy, albeit to a more limited degree.

Birth Defects

Birth defects are, of course, very concerning, but there’s no reason to think their rates are elevated in the case of surrogacy. And in fact, they aren’t. Consider first that the CDC’s canonical figure for the birth defect rate is 1 in 33, or 3%. Some studies covering this outcome have already been cited, but the general tenor of results from the 1990s and early 2000s was so unambiguous that this outcome is barely mentioned now. In general, studies find rates on the order of 1-2.5%, or exactly in line with common figures and perhaps better.

Birth defects are simply not a concern in relation to surrogacy.

Fertility Outcomes for Kids

A notable concern some may have is that by encouraging the use of ARTs and surrogacy for relatively infertile women specifically, we will effectively encourage future generations to use these techniques and technologies too. The reasons for this are two-fold. Firstly, by using them, stigma is reduced and use increases because relatively fewer people feel reluctant towards them. This has certainly been the case for IVF. Secondly – and this is the more concerning angle – technologically-assisted reproduction may produce future generations full of less fertile people.

It's not clear that reducing the stigma around IVF and other ARTs is in any way a bad thing. Without ARTs, millions of perfectly healthy people would not exist. Moreover, those with fertility problems would be less able or unable to have kids, and non-heterosexual couples might be unable to have their own kids as well. Because there will always be groups with fertility problems, reducing the stigma around IVF seems like it’s simply good because to the extent they supply demand, they grist the mill of technological improvement, reducing the costs and increasing the effectiveness of ARTs for future generations.

Some people may interject that the surrogacy conversation is premature because IVF itself is a problem, as it causes health issues in the resulting children, including a litany of cardiometabolic defects and asthma. But that is not the case, as negative IVF outcomes are virtually universally due to selection effects rather than effects of IVF itself. Using the asthma example, rates are similar for kids born by IVF or conceived naturally by subfertile couples. In other words, it is not the technique, but the people, and to argue against their use of IVF requires arguing that they should not be allowed to have kids at all.

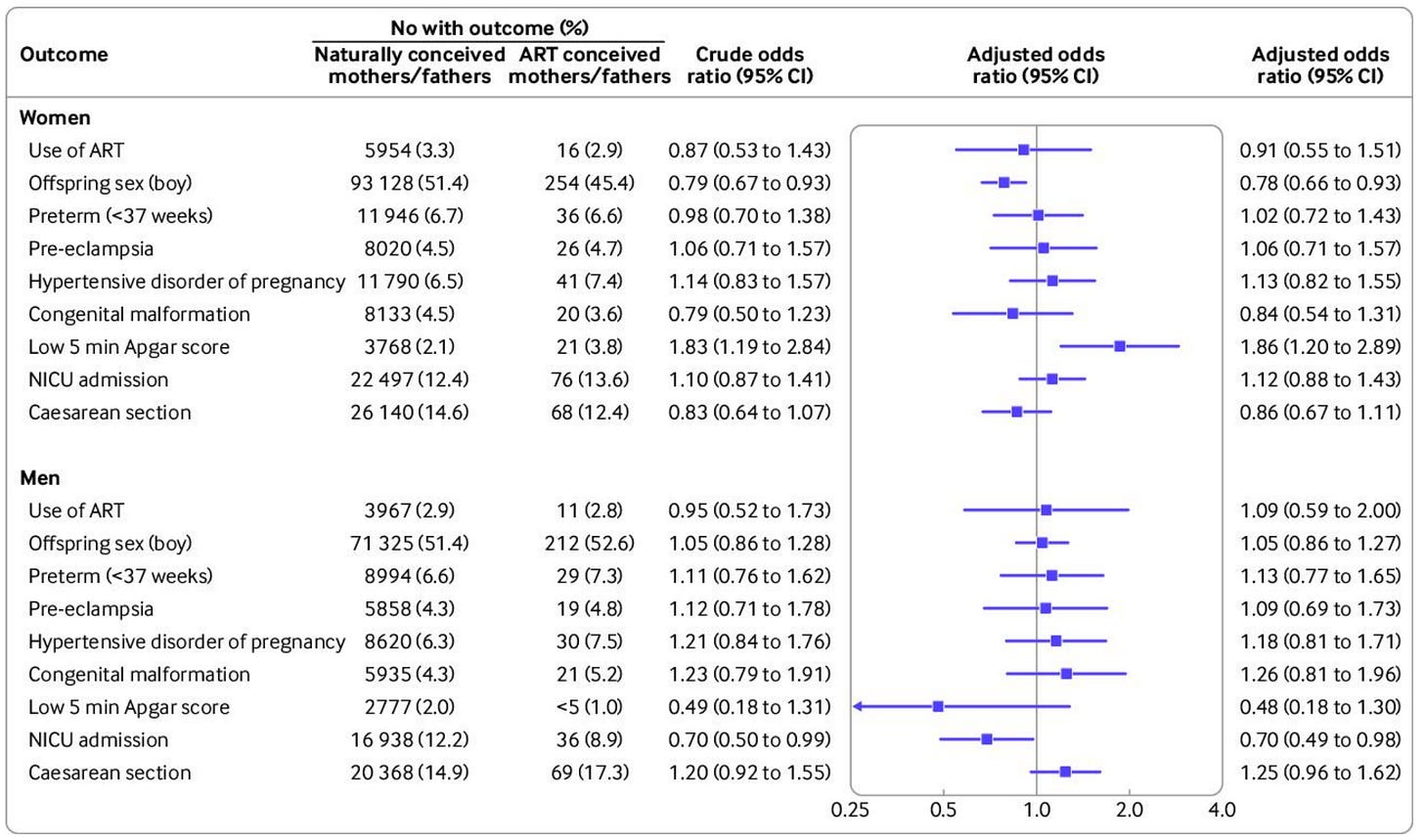

The second concern is hard to address because there are few publicly available datasets with linked multigenerational fertility observations and there hasn’t been much published on the datasets that do contain this sort of data. The best example we have is from a study by Carlsen et al. Comparing ART-conceived mothers and fathers to ones conceived naturally, there were about as many differences as expected by chance. Only two of the eighteen tests in the figure below were significant, and they went in inconsistent directions: one favored ART-conceived mothers and fathers and the other favored naturally conceived ones.

The most notable thing in the figure is that people conceived by ARTs weren’t more likely to use ARTs themselves, suggesting that if there’s an effect on usage rates via reduced social stigma, it’s not one from parents to children; instead, it’s more likely to be social spillover. The fact that the ART-conceived were not more likely to use ARTs also suggests that ARTs are not negatively impacting fertility, but it is important to note that the evidence here is still not exceptionally strong.

The idea that the use of ARTs or surrogacy may negatively impact the fertility of people whose fertility is limited by age or sexuality is baseless3, but the use of ARTs for conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome may be beneficial to the fertility of future generations, and especially when the object of discussion is surrogacy.

For the risk of birth defects or miscarriage – which has been observed to increase with age – it is undoubtedly the case that surrogacy helps to manage age-related risk, since surrogates tend to be young and they can be selected with age in mind if these are concerns. Taking Polycystic Ovary Syndrome as an operative example, the uterine hormonal environment may be one of the means through which PCOS is transmitted to future generations. A woman afflicted with PCOS opting for surrogacy may thus select a surrogate who doesn’t have PCOS or a related condition, decreasing her kids’ risk in the process.

Concerns about impacts on the fertility of future generations thanks to ARTs or surrogacy are currently unsupported.

Psychological Outcomes for Kids

As mentioned earlier, outcomes for children of homosexual couples are not meaningfully different from outcomes for children of heterosexual couples. Since the former are vastly more likely to have been adopted, surrogated, or born through IVF – and are thus much more likely to have been raised by someone who was not their biological mother – we can already be reasonably sure that surrogacy has no psychological impacts on the kids who are given up.

In fact, there are studies that have specifically followed surrogate children to assess their psychological health. Many of the studies in this literature were conducted by a single team led by Susan Golombok. Her work has shown that there are no major psychological effects of surrogacy by ten years of age. Shelton et al. found similar results in the U.K., as did Jadva et al. and Serafini. Finally, there was a recent systematic review of the literature by Carneiro et al. They documented similar levels of psychological adjustment among the children of gay and lesbian parents as among children with heterosexual parents. They even found some evidence that “surrogacy children with gay fathers present the lowest levels of psychological problems when compared to normative data.” If this is the case, it is likely due to selection.

Overall, psychological harms to kids appear to be minimal.

Psychological Outcomes for Mothers

The psychological outcomes for surrogate mothers themselves are a different question. There are country-level differences in how involved parents want to be with their surrogates following birth. However, most surrogates who stay in touch say that they’re happy with the level of contact. This matters given how plausible it is that surrogate mothers would experience grief as a result of not being able to see their children. But the literature indicates that the most common source of hardship for surrogate mothers is not lack of contact but rather relinquishment: giving up the child to the intended parents.

Several of the studies cited above looked at postpartum depression rates. For the general population, the rate is 6.5-20%; for surrogate mothers, the rate from these studies varies between 0 and 20%. There is therefore little evidence that relinquishing the baby takes a major toll on surrogate mothers. This is interesting because one would expect the rate of postpartum depression to be higher – perhaps much higher – among surrogates. But because they are psychologically screened prior to initiating surrogacy, it’s actually not obvious what to expect. It’s possible that surrogacy does raise the rate of postpartum depression, but surrogates were less likely to experience it to begin with. In any case, the evidence regarding postpartum depression is not consistent with highly elevated rates in surrogate mothers.

In one of the aforementioned studies, 35% had some or moderate difficulty handing over their child, but after one year, only 6% reported negative feelings. In studies from Iran and the U.K., 3% and 6.66% of surrogates reported that relinquishing was a source of hardship. A particularly revealing study found that a surrogate’s own children from before she became a surrogate were unaffected.

Overall, there is limited evidence that surrogate mothers experience psychological maladjustment. A sizable percentage of women, though less than half, struggle with relinquishing, but the extent is uncertain and they tend to recover in the vast majority of cases. The surrogate mother’s own children also seem to be unaffected by their mother’s decision to undergo surrogacy.

Psychological Outcomes for Intended Parents

Intended parents are typically elated when their surrogate child is born, though we can only be confident in saying this about intended mothers, as insufficient numbers of intended fathers have participated in surveys. We’re left with very little information for intended fathers, but marital quality does not seem to be affected. Blake et al. found that marital quality among surrogate families was no worse than among non-surrogate families after ten years. Another finding worth mentioning is that the fathers of surrogate children report less parenting stress than their counterparts in non-surrogate families.

A series of studies from the U.K. showed that being genetically related to children was important to the intended mothers of surrogate births, both during pregnancy and after the babies were born. This suggests there may be some negative psychological harm for intended mothers who don’t supply the eggs. By contrast, a study from the Netherlands did not find any couples with a surrogate child who were dissatisfied. This result is notable since it means they were satisfied even when they had a disabled child. I interpret this to mean that surrogate parents are just thankful to have a child at all.

Golombok et al.’s studies, discussed earlier, also found that surrogate parents were generally comparable to non-surrogate parents in psychological outcomes. The empirical literature on this outcome is not particularly large, but it’s arguably the least consequential of the outcomes I’ve mentioned. Why? Regardless of your view, you probably don’t put much weight on how the intended parents feel. They are the ones who initiated the arrangement, they are often the ones who are sometimes considered exploitative, and they are the ones who in rare cases completely abandon the surrogate mother. While it is reassuring that their marriages and psychological health do not seem to be affected, other concerns are more pressing.

Wrapping Up

Many are opposed to surrogacy. Yet there is little basis for such opposition in the literature on the psychological and physical health of surrogate mothers, surrogate children or the intended parents. All the relevant parameters appear to be normal in surrogacy. Debate over the practice should be constrained to the issues of economic exploitation and informed consent.

Regarding economic exploitation, the mother’s perspective is straightforward: she wants to make money and has an opportunity to do so. Many will agree that she should be free to engage in a voluntary transaction with the intended parents. There can be little room for debate if we wish to respect her reproductive agency. I think those who disagree will find themselves fighting an uphill battle like the one being fought by pro-life activists.

Informed consent is an issue that I believe can be handled through psychological screening. If the surrogate volunteers (i.e., does not demand payment), she is less likely to undergo psychological screening, and her ability to meaningfully consent may be more limited. But this is something that must be judged on a case-by-case basis. Perhaps IVF clinics could be regulated to include psychological screenings for all women who wish to become surrogates. However, I doubt this will happen, since there is no law against mentally unwell people having kids.

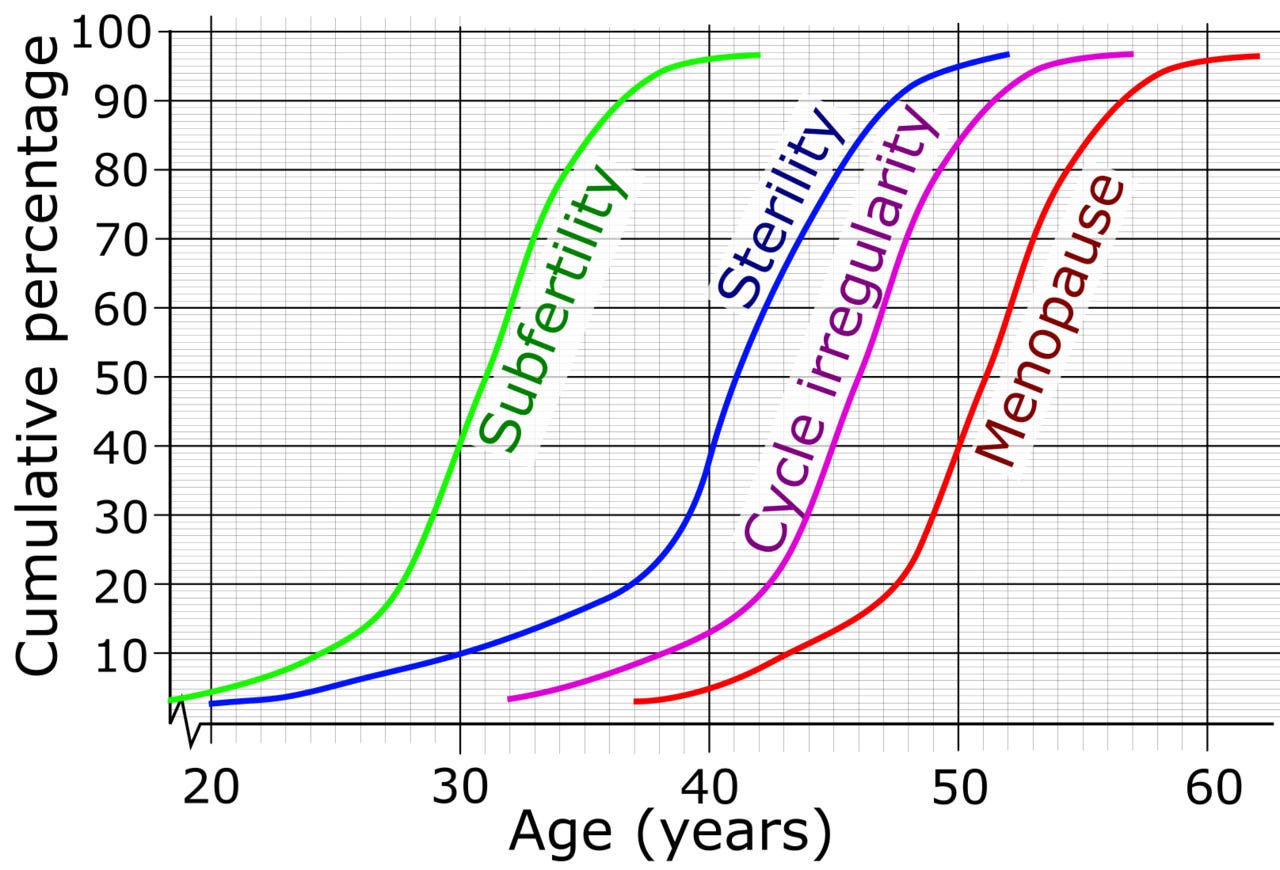

The relationship between age and fertility is very strong – something older and young women alike often find difficult to handle. Consider this stylized plot:

If women struggling with subfertility or sterility want to have kids, it seems perfectly reasonable to let them use surrogacy if everyone involved has given their informed consent. Until major (and currently unexpected) technological advancements are made, there is simply no other option for someone who wants to have a child that is their genetic offspring.

For those concerned about low birth rates, surrogacy can help to balance women’s fertility and career aspirations by allowing them to have children later in life. On the other hand, if the availability of surrogacy leads women to delay having children, it could actually reduce fertility. We don’t currently have any data suggesting that this happens, and because surrogacy is so expensive I’m skeptical that it does.

From a moral and a practical standpoint, surrogacy seems like an obvious win-win. In countries that have outlawed it, advocates can make a case that I believe is much stronger than the one their opponents can muster. With all the facts on the table, let’s debate.

Cremieux Recueil writes about genetics, 'metrics, and demographics. You should follow him on Twitter for the best data-driven threads around.

Out of all the years in this period, 2013 also had the lowest number of births.

More resources for 2020 are available here. Scrolling to the bottom of that page shows that a report with data through 2021 is already in the works.

One could argue that when older women have kids, their eggs are older and thus have accumulated mutations, but with frozen eggs this is not concerning at all, and in general, it isn’t either, since the rate of mutation accumulation is far slower in women than it is in men, where it is already so slow that individuals needn’t worry about it.

I think it lays out clearly that surrogacy is no more harmful than pregnancy and childbirth in other contexts.

However it's undeniable that pregnancy and childbirth cause harm; so the question is if it should be allowed in exchange for money, in particular. It seems obvious it causes considerably more bodily harm than sex, and it's illegal to pay for sex in some jurisdictions. I find it strange surrogacy is legal but prostitution is not in, say, the US.

And then one must ask why surrogacy is allowed but other forms of organ donation is not. I do see the difference with kidney donation- you lose one permanently- but not maybe with liver donation.

Never been prouder to be associated with Aporia- this based piece was desperately needed to clear up the completely muddled and unhinged conversation around surrogacy. Surely this article will result in the existence of some future happy healthy humans. Well done Cremieux!