Written by Randall Bock.

Liberals’ obsession with gun control promises a quick fix for murder rates, but the data—and the blood on our streets—tell a different story. From Black inner cities to the slums of Latin America, violence thrives not where legal guns are plentiful, but where culture fractures and policies fail.

This essay probes three questions: Does gun control reduce murder? Why do Black areas have such high rates of violence? And how have cultural shifts fuelled the carnage? The answers point not to firearms, but to the welfare and lax-on crime policies favoured by liberals.

Does gun control reduce murder rates?

The US homicide rate is over five times greater than the homicide rates of other top-tier nations, with guns accounting for nearly 80% of US homicides in 2020. However, these comparisons ignore critical differences. European nations have (until quite recently) been more homogeneous and socially stable. Venezuela and Mexico enforce strict gun laws but have even higher murder rates than America, while Switzerland and Norway—awash in legal firearms—are much safer. Blaming guns for murder is as shortsighted as blaming cars for drunken accidents and terror attacks in New Orleans, Magdeburg and Munich.

Homicide data alone do not capture the full picture—private firearms can function as a personal safeguard. The UK, while not in a state of war, faces growing civil unrest, with communities increasingly vulnerable to predation. Not uncoincidentally, knife crime there is burgeoning.

In the long run, the debate is not only about crime rates, but whether law-abiding citizens should retain the right to protect themselves if or when institutions fail (e.g., the Warsaw Ghetto). Western European crime patterns are also shifting with large-scale immigration—accompanied by censorship of issues like Islamic rape-gang violence, as seen in cases such as Rotherham. Sweden and the Netherlands, once paragons of safety, now grapple with gang violence and terrorism.

American gun crime is not driven by lawful owners. The extreme rarity of NRA members committing homicides—exemplified by the single notable case of William Sherwood, a lifetime NRA-member convicted of second-degree murder in 2014—shows that the organization's 5 million members contribute virtually nothing to the national homicide statistics. If there were more cases, the media would certainly highlight them, illustrating that legal gun ownership does not necessitate further gun control. Indeed, the absence of such coverage speaks volumes. Restricting legal ownership because of gun crime makes as much sense as banning pain medications because some people abuse them.

In the US, homicide rates track racial demographics, specifically the Black population share—not the scattered rifle racks of lawful owners. Liberal cities with strict gun laws often have among the highest murder rates. What’s more, there is no relationship between gun ownership and homicide rates across US states.

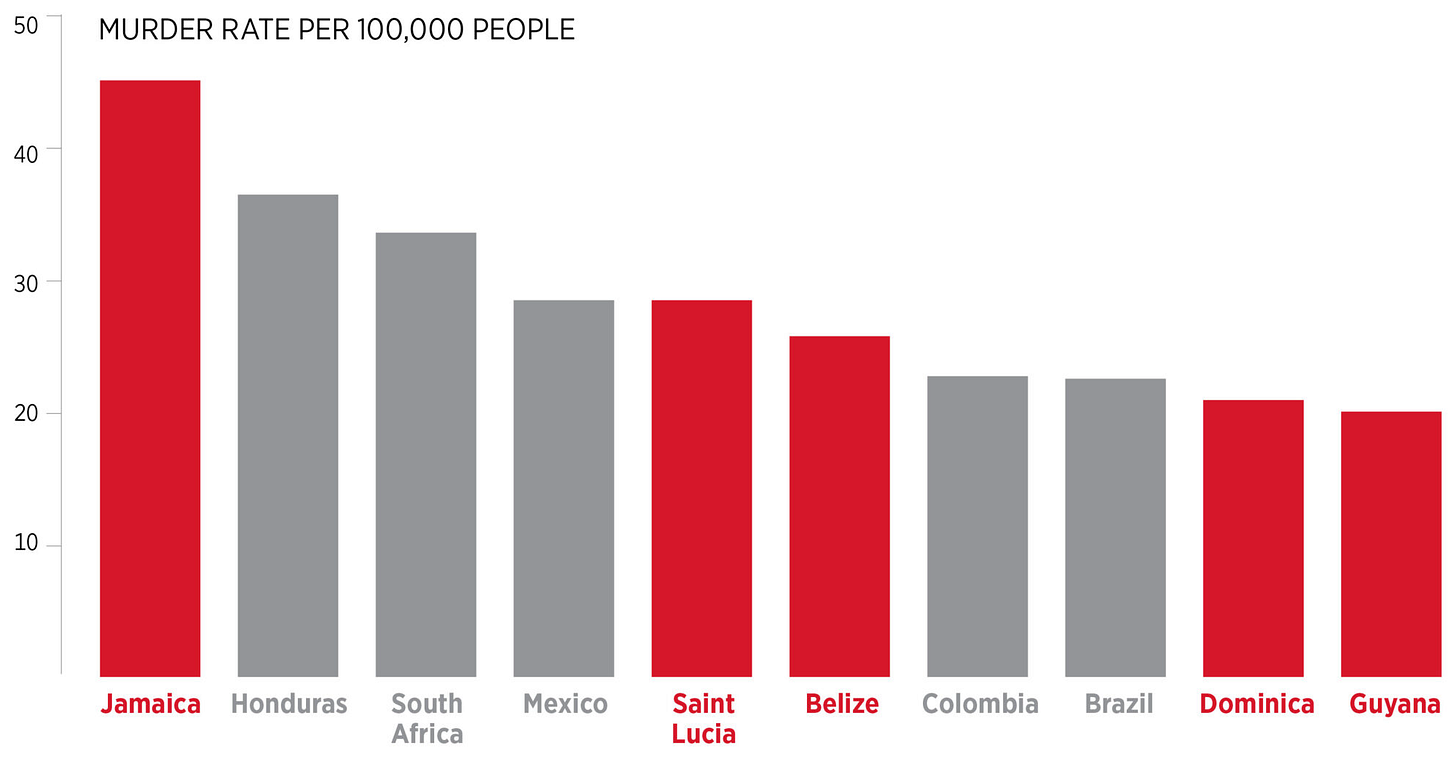

The problem extends beyond Black crime, however. Murder rates are even higher in Venezuela, Mexico and Honduras, where the populations are primarily “Latino”. These countries have their own mix of problems—poverty, gangs and a culture of machismo similar to the one in US Black communities. The Latin American experience also reflects fractured societies that have struggled under socialism, corruption and government mismanagement. In Venezuela, a collapsing economy has led to one of the highest murder rates in the world. Socialism breeds hopelessness, and hopelessness breeds violence.

Why are Black areas so violent?

In 1983, Black Harvard’s Professor Alvin F. Poussaint (who shaped the Bill Cosby Show’s “positive images of parenting and father involvement”) noted:

Black homicide rates are seven to eight times those of whites ... Today, homicide is the leading cause of death among young Black men, and contributes significantly to the shortened life-span of the Black male. In about 80-90% of the cases, the Black victim was killed by another Black.

In 40 years, not much has changed. The murder rates in predominantly Black urban areas are sky-high. Cities like Chicago, Baltimore, and St. Louis are drowning in blood, and the victims and perpetrators are overwhelmingly Black.

Indeed, the United States’ “unexpectedly” high murder rate is due largely to violence concentrated in areas with high Black (and to a lesser extent Latino) population shares—absent which, the country’s homicide rate would align more closely with Europe’s.

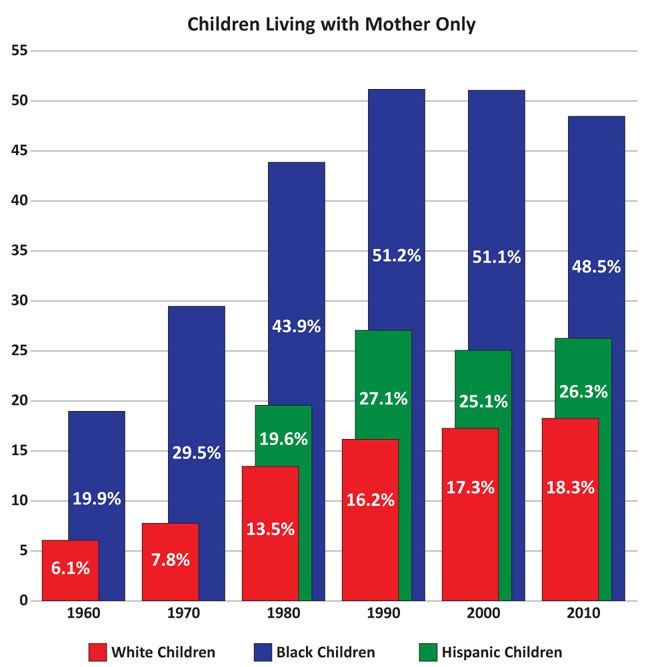

What's driving this violence? It's a combination of idolizing toughness, the draw of gang culture, widespread fatherlessness, and the failure of public institutions. Without fathers, too many Black teens have turned to gangs for a sense of family, believing respect can only be earned through violence. Legacy media and TV have certainly played their part by popularizing “gangsta culture”.

There's a clear gender divide too. It's the boys and young men who suffer most in this scenario, growing up in homes led by single mothers, missing out on male role models. Consider LeBron James, born to an unattached mom prone to crack addiction, yet fortunate in that she was yet wise enough to let him be taken in by a cohesive family. Akron’s Frank Walker provided the discipline and direction the young James needed.

The genetic hypothesis

Some argue that black crime is a product of genetic inheritance. For example, Emil Kierkegaard maintains that violent behavior, which is highly heritable, varies in frequency across ancestries—being more common among Africans and less common among Asians. Testosterone, a known driver of aggression that explains the 8-to-1 male-female homicide gap, may amplify this, with Blacks’ showing 2.5 to 4.9% higher average levels than other groups.

Genetic explanations aren’t off-limits: the Y chromosome’s obvious link to violence proves it. Yet within same-race cohorts, culture often trumps genes. Charles Murray’s Coming Apart tracked Whites alone, finding disciplined communities prosper while others crumble. Mormons outpace background Protestants, despite shared roots.

Southeast Asia’s Cambodians and Vietnamese lag somewhat, but their US-raised kids excel, lifted up by stability and grit. The Mariel boatlift dumped Cuban criminals on our shores, yet no lasting crime wave followed (as compared to national trends). Australia, a former penal colony, now boasts an 99 IQ and low rates of violence—hard work reshaped its legacy.

African immigrants, who’re often more genetically “African” than African-Americans (owing to lower admixture), thrive here. So do more religious Blacks, hinting at culture’s influence. Nigerians hit the ground running—arriving with degrees in hand and a hunger to learn. They pass on this education-impetus like a family heirloom, pushing their kids toward college and beyond, sometimes outpacing native-born Whites in a single generation.

Still, Kierkegaard notes a stubborn pattern: Africans have elevated crime rates even at higher incomes, outpacing Whites in poverty-income percentiles. This persists in Brazil, where Black crime exceeds non-Black crime in 25 of its 26 states.

But history’s shadow isn’t fixed—Barbados and Jamaica offer a striking comparison. Barbados and Jamaica share a nearly identical West African slave heritage, with both currently about 90% ethnically derived from this background. Yet their outcomes differ starkly—Jamaica has four times the homicide rate of Barbados.

The inverse relationship between IQ and crime is undeniable—higher crime correlates with lower IQ—but the cause is less clear. Persistent crime and societal challenges may depress IQ over time. Effective governance, community cohesion and a commitment to maintaining societal stability—rather than genetic differences—seem to explain Barbados’ success and Jamaica’s struggles.

Recent history proves that things can change quickly. El Salvador has seen its homicide rate plummet more than 10-fold in recent decades—despite no major demographic changes. Leadership and policy can sharply reduce violence, regardless of inherent traits.

The impact of the Great Society

The Great Society’s war on poverty destroyed the Black nuclear family by rewarding single motherhood and fostering dependence. Black incarceration rates then skyrocketed—not due to arbitrary or “systemic” racism, but in response to rising crime. The chart below, taken from the paper ‘Exclusion and Exploitation: the Incarceration of Black Americans from Slavery to the Present,’ illustrates two key trends: a period of stasis or mild decline in incarceration from the 1920s through the 1970s (at a time with much worse racism) followed by a sharp rise coinciding with the Great Society programs.

Yet the author, Christopher Muller, never once mentions Lyndon Johnson or The Great Society, instead attributing the increase to various structural forces. He emphasizes declining demand for agricultural labour, deindustrialization and economic exclusion—but never the actions of those arrested and imprisoned.

We can’t run a lab experiment to rewind the Great Society and test its effects—social science is stuck with the messy reality of history. But here’s the kicker: the early 20th century, with its raw, unfiltered racism—including lynchings and Jim Crow—didn’t produce the incarceration or crime spikes we saw after the 1960s. Muller never touches the heart of it. The road to hell, as they say, is paved with good intentions—and this one runs through broken homes.

Narratives of blame

The left-wing writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, from his privileged perch (and Black Panther paternal lineage) dismisses the visceral, street-level fears of crime as overblown and regressive, downplaying Adam Walinsky’s 1995 warning, “We shrink in fear of teenage thugs on every street. More important. We shrink even from contemplating the forceful collective action we know is required.”

Coates takes a similarly supercilious approach to Jesse Jackson’s famous confession of relief upon realizing the footsteps behind him belonged to a White person, not a Black one. He sees Jackson’s fear as an unfortunate byproduct of racist oppression rather than a rational response to statistical reality. We are told that acting on those fears—whether through policy or personal caution—is unjustified because it risks reinforcing racial disparities.

Coates claims Black communities are victims of “resource extraction” (leaving unsaid precisely which resource or how their station differs from other groups’ within the economy). Coates states that “Blacks tend to live within more “criminogenic conditions” but fails to confront how internal cycles of violence perpetuate precisely those conditions. His proposed solution—reparations—echoes the same welfare-driven approach that fractured families under the Great Society.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Al Sharpton, and Ibram X. Kendi—along with the broader "antiracist" movement and BLM—continue to frame every social disparity through race. Yet day-to-day racial tensions have eased. The best proof of progress? Interracial marriage acceptance, once a cultural flashpoint, is now a non-issue for most Americans.

Despite documented declines in prejudice from the White majority, the media amplifies racial grievance narratives, fostering a false perception of worsening bias. The relentless framing of White guilt by the racism industry may well be fueling division, planting seeds for a self-perpetuating cycle of resentment and violence. This imbalance warps public understanding. When Whites are perpetrators, it’s headline news; when the reverse is true, the story gets memory-holed.

Call it harsh, but the antiracist gospel—Coates, Kendi, Sharpton—has doubled down on a Black community already battered by crime and despair, peddling victimhood while flash mobs loot with impunity.

Cultural decay and self-reliance

Thomas Sowell’s Black Rednecks and White Liberals delivered a searing, fact-driven indictment of the misguided White Liberal paternalism that has undermined Black communities in America. Sowell demonstrates how a once-thriving Black population, which had been making steady progress through the mid-20th century—marked by stable marriages, church-going, intact family structures, greater literacy and upward mobility—was derailed by LBJ’s destructive social policies.

Bill Cosby, once revered as “America’s Dad,” used his platform to call for Black self-reliance, warning against a culture of victimhood and generational dependence on government. Yet his own moral failures obliterated his credibility, turning his once-powerful message into a cruel irony. Meanwhile, scholars like Sowell, Glenn Loury, Larry Elder, Shelby Steele and Wilfred Reilly continue to advocate personal responsibility (though none have ever commanded the mass appeal Cosby once wielded).

While Cosby squandered his influence through disgrace, Barack Obama fumbled his through duplicity: speaking of Black responsibility while simultaneously fuelling grievance politics, embracing Trayvon Martin as a personal symbol, and supporting Black Lives Matter.

We are now witnessing the full realization of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ vision of decriminalization, and the results are anything but uplifting. Today’s roving flash mobs, clearing out stores with impunity, are a direct product of the Ferguson effect. This is precisely the scenario Heather Mac Donald warned about in The War on Cops: when policing retreats, crime surges, and the very communities activists claim to protect suffer the most. The 1990s’ proactive policing saved thousands of minority lives, gains now reversed by anti-police rhetoric.

A path forward

The fact that societies sharing similar linguistic, cultural and genetic backgrounds can have very different homicide rates illustrates that social structures and public policy matter. Western Europe, with its history of functioning civil societies, has managed to maintain lower homicide rates—despite recent immigration from outside Europe. Meanwhile, parts of Eastern Europe (including Ukraine, Russia, Albania and Latvia) have not. There was effectively zero personal crime reported in Mao’s China and Stalin’s Soviet Union (most crimes were committed by the state itself). So freedom includes a freedom to do ill, as well as to do good.

Outside of an authoritarian state with social credit scores, the best way of reducing violence lies not in stricter gun control but in fostering environments where economic, religious and social opportunities abound. The Trump administration’s pre-covid era was the first time in four decades where opioid deaths fell.

This isn’t about drafting a 10-point plan—it’s about stepping back to when Black marriages, literacy, and jobs climbed steadily before the Great Society’s meddling. Welfare and lax-on crime policies haven’t lifted Black America—they’ve crippled it, replacing dignity with dependence and fatherhood with a government check. Affirmative Action and DEI haven’t fostered excellence—they’ve lowered the bar, breeding resentment against Whites and Asians.

Gun control is a distraction. The real problem is a culture of grievance, rage and lawlessness, excused by cowardly politicians. A man with nothing to lose, filled with resentment, is far more dangerous than any firearm.

Randall Bock is a physician and writer with diverse interests, including addiction, public health and gun violence. He is the author of Overturning Zika: The Pandemic That Never Was.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

Jamaica was probably a lot more peaceful in the years immediately preceding independence, when both Ian Fleming and Noel Coward had their primary residences there.

It would be interesting to look at a combined homicide + incarceration rates statistics and see if that tracks more accurately across demographics- Bukele famously slashed murder rates by essentially locking up every major criminal gang in the country. But the point is taken.