Murder as measuring stick

How medicine has masked a colossal rise in crime and disorder since the 1960s.

Written by Arctotherium.

Comparing crime rates between countries or across time is hard. Definitions shift, unpunished crimes go unreported, the quality of statistics varies, and what constitutes a crime changes. The exception is murder: both its definition and reporting are consistent between countries and across time. Hence murder rates are often used as a proxy for crime rates.

Murder rates as a function of medicine

Although the murder rate is insulated from reporting and definition shifts, it is very strongly affected by medical care – both improved techniques and better access. A fatal injury in 1960 might be easily treatable today. To put it in concrete numbers: if aggravated assaults in the United States had been as lethal in 1999 as they were in 1960, the murder rate would have been 3.4 times higher (Harris et al., 2002).

This is big, especially considering that 1960–1999 is not that long a period in historical terms. The already massive difference would be even bigger over a longer time scale. Closer to the present, both medical techniques (such as the rise of minimally-invasive surgery) and transportation/communication technology (such as smartphones) have improved significantly in the 21st century. And imagine trying to use murder rates to compare crime levels between the present day and the era before antibiotics (not widely used until World War II) or the era before germ theory.

Taking this into account, I would estimate that a murder today represents 4-5 times as much crime and disorder as a murder in 19601, and probably 10 times as much as a medieval murder, with the early 20th century somewhere in between. As such, today’s murder rate being comparable to that of 1960 represents a colossal failure of justice, with overall crime and disorder being several times higher than it was two generations ago.

Why does this matter? The major costs of crime are not from murder, because murder is rare and highly concentrated in a few demographics. They are from more common crimes like assault, mugging, burglary, housebreaking and rape, as well as general public disorder (both directly and in the huge costs people pay to avoid it). Murder is a reasonably good proxy for these things in the short-run because all crime and disorder tends to go together. But the ratio of murder to crime and disorder declines quickly over time. A murder rate of X even in the recent past corresponds to a lower crime rate than a murder rate of X today. Discourse about crime and its prevalence must take this into account.

International Comparisons

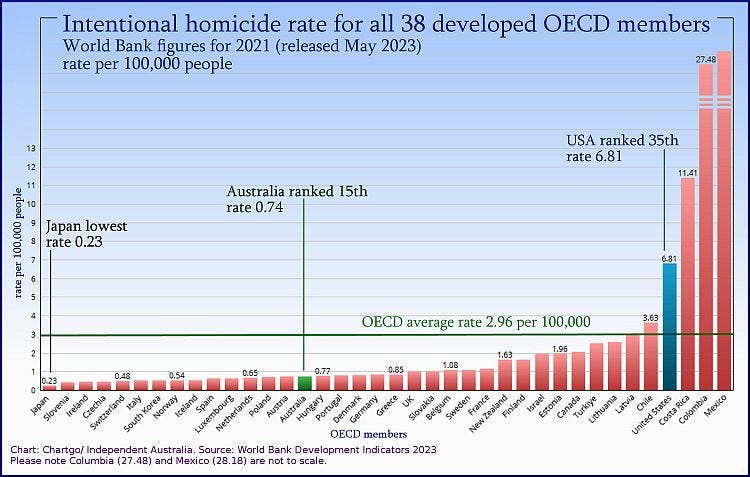

The ratio of murder to crime and disorder doesn’t just drop with technological advances. It also varies between countries. It’s impossible to give a precise number because of reporting differences in non-murder crimes between countries, but we can still derive an estimate. For instance, the United States has a murder rate several times that of other developed countries.

But international victim surveys with a consistent methodology show the US to have similar overall crime rates as Canada or Europe. The major reasons for the high American murder rate are probably Americans using highly-lethal guns (rather than knives or fists) and blacks (who are responsible for more than half of US murders) being more likely to commit impulsive murders rather than property crimes.

The implication is that New York, for instance, is not several times more dangerous than London or Paris, but merely more murderous. Since murder is arguably a proxy for what we care about, rather than what we care about itself, this is very important. When Europeans talk about their cities becoming unsafe, we should believe them – even if their murder rates are still rock-bottom by American standards.

Anti-Crime Secular Trends

If Western criminal justice systems were merely as effective as they were in 1960, and Western populations have a similar genetic propensity to commit crime, we would naively expect crime to fall over time, as has happened in Japan, for the following reasons:

Obesity. Despite being of lower socio-economic status and intelligence, obese people are much less likely (about 20-25% per 5 BMI) to commit violent, property, and drug crimes than their normal-weight counterparts. The evidence isn’t overwhelming (you can’t do an RCT), but there are plausible reasons, such as lower testosterone and the physical difficulty of committing crimes, to believe this relationship is causal. Over the past 40 years, average BMI among young adults (18-25) increased by 4.5 points in the US. Without this, it’s reasonable to assume that crime rates would’ve increased further.

Wealth. 21st century Western societies are vastly wealthier than their 1950s counterparts. To the extent that wealth causally reduces crime, we would expect crime to drop.

Forensic technology and surveillance. In the 21st century, surveillance is ubiquitous and we have DNA evidence, GPS data, and numerous other modern forensic tools. It should be much harder to get away with crimes today than it was in 1960. And since the vast majority of crime is committed by repeat criminals, who it would be easier to apprehend near the beginning of their sprees, one would naively expect this alone to significantly reduce crime. But clearance rates have instead plummeted2; it’s much easier for the typical criminal to get away with it. How much worse would this be without technological advances?

Aging. Every developed country has gotten significantly older since the middle of the 20th century. Given the importance of the age-crime curve (the vast majority of crime is committed by young men), this would be expected to drive crime down.

The fact that crime and disorder are several times worse today than in 1960 in most Western societies (albeit better than the 1990s) is a sign that something is very wrong.

Ultra-Low Crime Societies

Modern-day Singapore and Japan are justifiably admired for their extraordinarily low murder rates (0.1/100k and 0.23/100k, respectively), and these murder rates reflect near-zero levels of crime and disorder in society at large. This has massive benefits. Blue-collar property and violent crime cost around 2.6 trillion dollars per year (about 12% of GDP) in the United States. But this doesn’t account for the massive lifestyle changes people make to avoid it. In Japan or Singapore, you can go wherever you want alone at night, leave children unattended, travel however you want (no need to stick to sealed-off cars), leave expensive possessions unsecured in public areas, and live anywhere you can afford (with corresponding cost-of-living benefits). No urban cores hollowed out by crime means shorter commutes, better amenities, and more efficient use of land.3

But these two wealthy, aged East Asian societies are not the only ultra-low crime societies to exist. Mid-century England had about four times the homicide rate of modern Japan4, which, given advances in medical care, implies it had similar levels of crime and disorder5. This with an average age of 34, 15 years younger than the median Japanese person today!

And it’s not just England. Other parts of postwar Western Europe also had extraordinarily low levels of crime 1950-1974.

Postwar Western European countries were among the safest on Earth, comparable to much older, much wealthier, and much more forensically sophisticated modern Japan. There’s no technical reason why Western European societies today shouldn’t be this safe, and reap the benefits, beyond a lack of will.

Lock Them Up

Fortunately, crime is an exceptionally tractable problem, because the overwhelming majority of crime is committed by a tiny minority of very prolific offenders. For instance, in Sweden 1% of people are responsible for 63% of violent crime convictions, with about half of all convictions being accounted for by people with three or more previous convictions. You could cut violent crime in half by simply executing (or imprisoning for life) people with many previous offences. The United States is similar, with more than 75% of people in US state prisons having five or more prior arrests.6

The same stylized fact whereby a tiny, very criminal minority commits the vast majority of crime also holds for non-violent offences. For instance, 327 people were responsible for a third of shoplifting arrests in New York City in 2022, having been arrested and rearrested 6,000 times.

These supercriminals are well-known to police and, by virtue of committing so many crimes, their guilt is not in doubt. The only obstacles to executing or permanently imprisoning them are legal and procedural. Most of these legal and procedural barriers7 were put in place in the 1960s and 1970s8, as a natural consequence of politicians and judges9 adopting a left-wing view of criminals as victims of society, rather than the other way around. Remove these barriers and return to punishing criminals quickly, surely and harshly (with a focus on incapacitation or execution10, not rehabilitation), and crime can be quickly brought under control.

False Positives

The most common objection to quicker, surer, harsher sentencing, and especially the death penalty, is that it will lead to more innocent men being punished. On utilitarian grounds, this might be justifiable11, but people tend to be suspicious of this sort of reasoning. Fortunately, however, a stricter regime does not necessarily imply more false positives, for the following reasons:

Most crime is committed by well-known prolific criminals. When dealing with someone who’s already committed dozens of assaults, you’re not at risk of accidentally punishing an innocent man. These people’s guilt is not substantively in doubt; the fact that they are free to commit crimes to begin with is damning.

Lower crime rates mean more resources can be devoted to each crime. The American system cannot afford to exhaustively investigate and prosecute more than a tiny fraction of crimes, leading to a reliance on plea bargains. If American crime rates were 4x lower, as they were two generations ago, we could afford to be much more careful when dealing with each individual crime.

Lower crime rates mean fewer absolute false positives. Imagine that the Japanese justice system had 10 times the false positive rate of the American.12 The United States has about 50 times the murder rate of Japan, so Japan would still have only ⅕ the number of false convictions for murder per capita.

As such, a quicker, surer and harsher criminal justice regime would be expected to lead to fewer false positives, not more. It may be better that 10 guilty men go free than one innocent be punished – but that’s why we should be tougher on crime.

Conclusions

Crime rate comparisons often rely on the murder rate to account for reporting differences and definitional shifts for other offences. But these comparisons must take into account the fact that the murder to crime/disorder ratio is constantly falling, having dropped by a factor of 3.4 in 1960-1999 alone. Any analysis that doesn’t account for this will be very misleading. Once this is adjusted for, two things become clear:

In both Western Europe and the United States, the mid-20th century was several times safer than today, despite being younger, poorer, thinner, and having far worse forensics. We’ve clawed back some ground since the 90s, but we’re still very far from where we were. Nostalgia for a safer past is correct.

Several postwar Western European societies were about as criminal as modern Japan (while being much younger, poorer, and having far worse forensics).

As such there’s no good reason European countries today (and ideally the United States) shouldn’t be as safe as Japan. All it would require is a criminal justice system as effective as it was two generations ago. Doing this would be just, would make us wealthier, and would vastly improve our quality-of-life. Reaching Japan is realistic and should be the goal of Western criminal justice politics. Accept nothing less.

A slightly different version of this article was originally published at Not With A Bang.

Arctotherium is an anonymous writer interested in demographics and the future of civilization. You can find more of his writings at his blog Not With A Bang or at his Twitter.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

The analysis in Harris et al. can and should be extended to 2019 (there are some reporting issues post-Floyd), and ideally done in other countries as well. If someone reading this wants to do this, DM me on X. Unfortunately, due to the lack of reliable non-murder stats, it can’t be extended very far into the past, though it might be possible to use 1930 rather than 1960 as the baseline.

The US homicide clearance rate has dropped from about 90% in 1960 to about 50% today. By comparison, Japan’s clearance rate is 93% for all major crimes (murder, robbery, arson, rape, sexual assault, indecent assault, kidnapping, and human trafficking). We have the technology!

A 10% increase in crime in a city on average leads to a 1% population decrease. Urbanists take note.

By comparison, Japan itself had a homicide rate around 3/100k in the 1950s, which implies Japan has gotten several times safer since then – as you’d expect, given the anti-crime trends listed above.

This should put into context Lee Kuan Yew’s astonishment at how London was able to have unattended newspaper stands with a cash box operating purely on trust.

Keep in mind clearance rates. Someone who’s been arrested five times for assault has probably assaulted literally dozens of people.

Among the worst of these is leniency towards juvenile offenders. Committing crimes early is one of the best predictors of committing more severe crimes later. Youth should be an aggravating, not mitigating, factor and would-be supercriminals should be removed from circulation quickly.

This is why I have neglected to take mass immigration into account. Immigration does contribute significantly to crime in Continental Europe (in the US and Britain, immigrants are about as criminal as the population average), but the huge rise in crime and disorder began in the 60s/70s, before significant demographic change.

Mostly the latter. The electorate is, as a rule, anti-criminal. In the United States, most of this revolution can be chalked up to the Warren Court.

Executions would also make prisons much more humane. Execute the worst 50% of prisoners and there would be a lot more space for the majority of criminals who are not serious multiple offenders and who are to some extent by victimized by proxy.

Paul Cassel (2018) estimates the odds of being falsely convicted for a violent crime to being the victim of a violent crime in the United States to be around 30,000 to 1.

To be clear, there’s not a shred of evidence that Japan has a higher false positive rate, much less one 10 times higher.

“Murder is a reasonably good proxy for these things in the short-run because all crime and disorder tends to go together.”

That seems likely for earlier eras but I wonder how much property crime, rape, etc. have declined due to cameras being ubiquitous. Significantly I would bet.

You make some interesting observations. Some of this is definitely true- for example, the US does not have an unusually high rate of non-violent crime, compared to, say, Europe or the rest of the Anglosphere. It really *is* more violent, though, and this isn't just down to higher firearm availability; the US has more violent offences across the board.

But your key point is almost totally devoid of evidence; you don't actually have any good evidence that crime is rising. All statistics show that it has been broadly falling (with a few blips, of course, both for certain kinds of crime and in certain short periods) since the early-mid 90s, and this is not just murder rates. The only hard evidence in this article is the lethality rates graph, but that's obviously heavily confounded by reporting and categorisation; how do we know that an "aggravated assault" is the same thing in 1970 as now?

I personally do not believe that crime rates, either in general, or specifically violent, are many times higher today than they were in the early 20th century.