Written by Aaron Dymarskiy.

Last month, I had the pleasure of meeting Professor J. Michael Bailey at the Freedom of Intellectual Navigation Conference, which inspired me to finally read The Man Who Would be Queen (2003), after having put it off for some time.

What struck me most about the book was how little of it was about autogynephilia,1 and how much of it was about gendered childhood behavior. Regarding the latter, there is a short section asking whether or not such behaviors are innate. To answer this question, Bailey refers to a few anecdotes concerning boys who were raised as girls due to rare congenital disorders.

The most remarkable story was about a boy who had to undergo castration at birth and, subsequently, a sex change surgery, due to a life threatening disorder. The surgeon told the boy’s parents that they should raise him as if he were a girl, to which they agreed, naming him “Amanda”. However, it was impossible to keep up the illusion: Amanda did not play like girls typically do, favored masculine cartoon shows over feminine ones, refused to wear pink clothes, and typically chose male playmates. At Amanda’s fourth birthday party, one parent joked, in her ignorance, that she believed the celebrant “was meant to be a boy”. At age 7, the boy learned the truth from his parents, and stopped going by the name Amanda. He quickly adjusted to living as a boy, with easy acceptance from his schoolmates.

Such cases are very interesting on their own, but cannot tell us much without being quantified and compared to suitable controls. When this is done, they offer illuminating evidence relevant to the question: How much of the “arbitrary” differences in behavior between girls and boys, such as what toys they play with, can be explained by how they are raised, and how much by innate differences between them?

Toward the end of the article, I review a large study of boys like Amanda, to test what might be called the “nature hypothesis”. Before that, I analyze two additional lines of evidence: the behavior of nonhuman primates and studies of girls with congenital disorders that increase their testosterone.

Non-human primates

Evidence of sex differences among gorillas, chimpanzees and other non-human primates is often used to support claims about the origins of sex differences among humans. I will not spend much time on this part of the argument, as I find it much weaker than the others—for a few reasons.

It is difficult to know if the sex differences in nonhuman animals are actually similar to sex differences among humans; there is no standard way to compare these differences across species. Take as an example the fact that, in one species of fish, females use pink bellies to attract mates (LaPlante & Delaney, 2020). Is this related to human females’ preference for the color pink? Maybe, but maybe not—after all, preference for pink begins in infancy among girls, so it is difficult to imagine that it is related to sexual selection among fish. One must be careful not to overstate similarities here.

The best review I could find was published by Elizabeth Lonsdorf (2017) in a special issue of the Journal of Neuroscience Research about sex differences. She cites three findings that appear to support the nature hypothesis:

Male rhesus monkeys in captivity prefer playing with toy cars. Females, on the other hand, preferred dolls and pots in one study, though this was not replicated in another. (The male finding was replicated.)

Young male chimpanzees were found to engage in more object-oriented play than females.

Infant female chimpanzees, gorillas, macaques and monkeys have been found to engage in “forms of play parenting”, sometimes by carrying other infants, or by carrying objects resembling them (e.g., sticks).

The evidence presented in this review does seem somewhat persuasive. But, again, it should be emphasized that it is difficult to know how well these sex differences among primates reflect differences among humans, even accepting that they are superficially quite similar.

Furthermore, there is a dearth of quantitative studies on the topic, and it is unclear whether null findings would be published or included in reviews such as Lonsdorf’s, or, for that matter, if null finding would even be interpreted as null findings. It is of course true that there are sex differences among primates, but in order to serve as proof that human sex differences are innate, these differences must be shown to be of the same kind as the differences among human boys and girls.

Despite these caveats, I think that it would be dishonest to deny that the evidence favors the nature hypothesis. As Lonsdorf herself concludes:

There are diverse lines of evidence for sex differences in play behavior in many primate species. Indeed, these sex differences in play may represent evolved predispositions that reflect patterns of mating competition and parental investment that are shared by most mammalian species.

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

The second line of evidence comes from girls with CAH, a group of disorders that affect the adrenal glands. Of interest is the fact that CAH causes overproduction of androgens, and thus makes girls more masculine. This provides a great natural experiment: if girls who get a higher dose of androgens show a stronger propensity to engage in seemingly arbitrary male behavior, then the sex differences in the general population must be partially explained hormonally (and thus by nature).

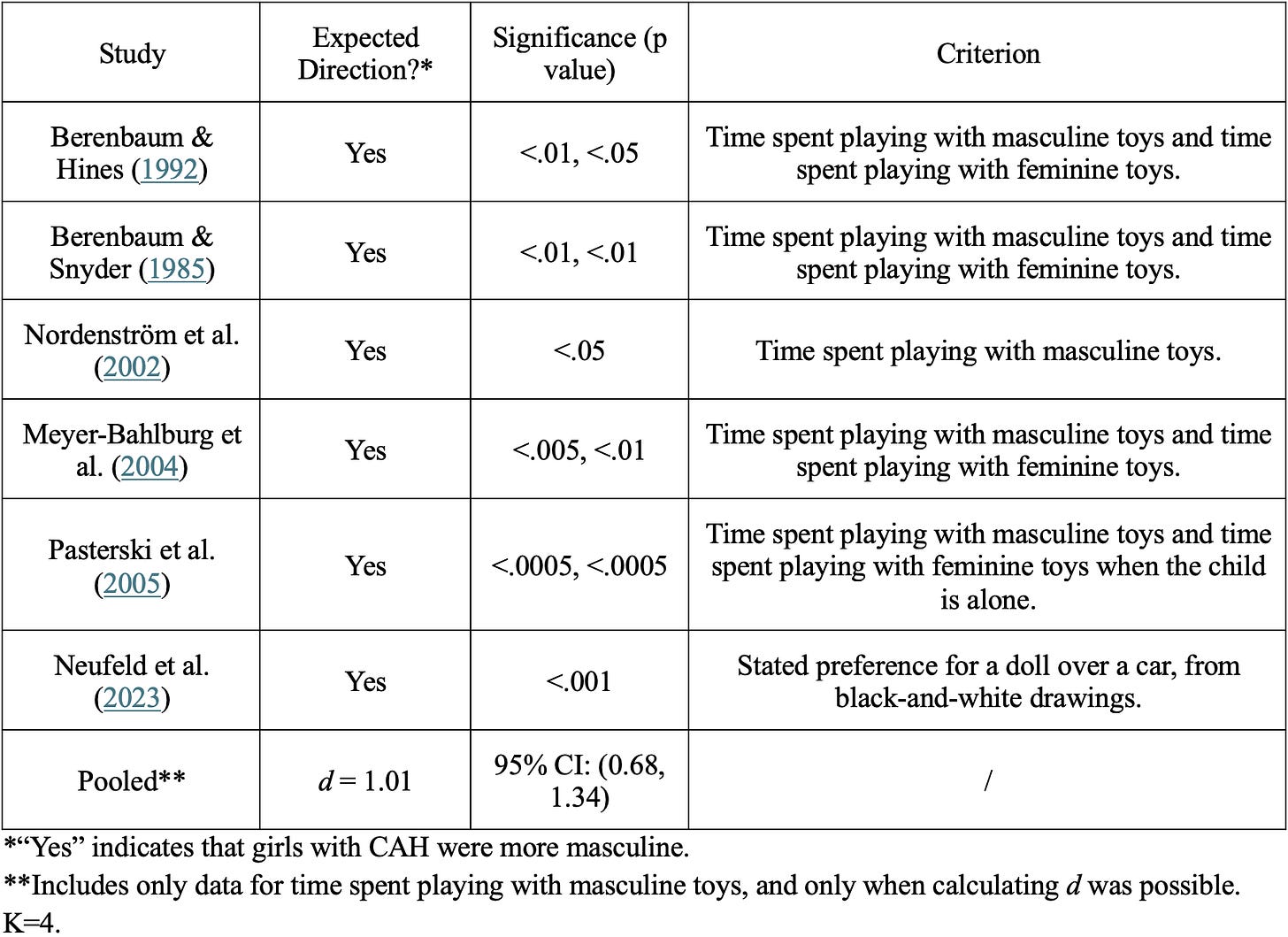

The following table summarizes the results from the studies I was able to find comparing girls with CAH to controls on measures of toy preference, all of which found statistically significant effects in the expected direction (that is, CAH girls having more masculine toy preferences). The bottom row shows the result of a pooled analysis of four studies that used the same measure and provided enough information. The overall effect size, a d of just over 1, is huge, and explains how all of these studies were able to find statistically significant results despite having low sample sizes (typically about two dozen girls in each group).

One of the six studies also assessed color preference using light pink and dark blue squares (Neufeld et al., 2023), finding a statistically significant difference in the expected direction. However, when light blue was used rather than dark blue, the difference was very small and non-significant, implying that the lightness, and not the color itself, may be responsible for the observed difference.

It should be noted that boys’ testosterone also increases slightly if they have CAH, but this effect does not result in as large a change in overall T, as almost all their testosterone comes from their testes, rather than the adrenal gland. Several of the studies included in the table had a male CAH group, and none found a significant difference in masculine play behavior between boys with CAH and those without it. The study that tested for color preference also found no difference between its CAH and non-CAH groups of males.

Boys with Disorders of Sex Development (DSD)

There are several conditions affecting males that cause them to have sexual characteristics similar to girls at birth, generally referred to as DSD. These males are raised as girls—as was the case with Amanda—and only begin to live as boys when they reach puberty and start to look sex-typical. Because boys with DSD are sometimes reared as girls, one can examine how they differ from those who have the same condition but were raised as boys.

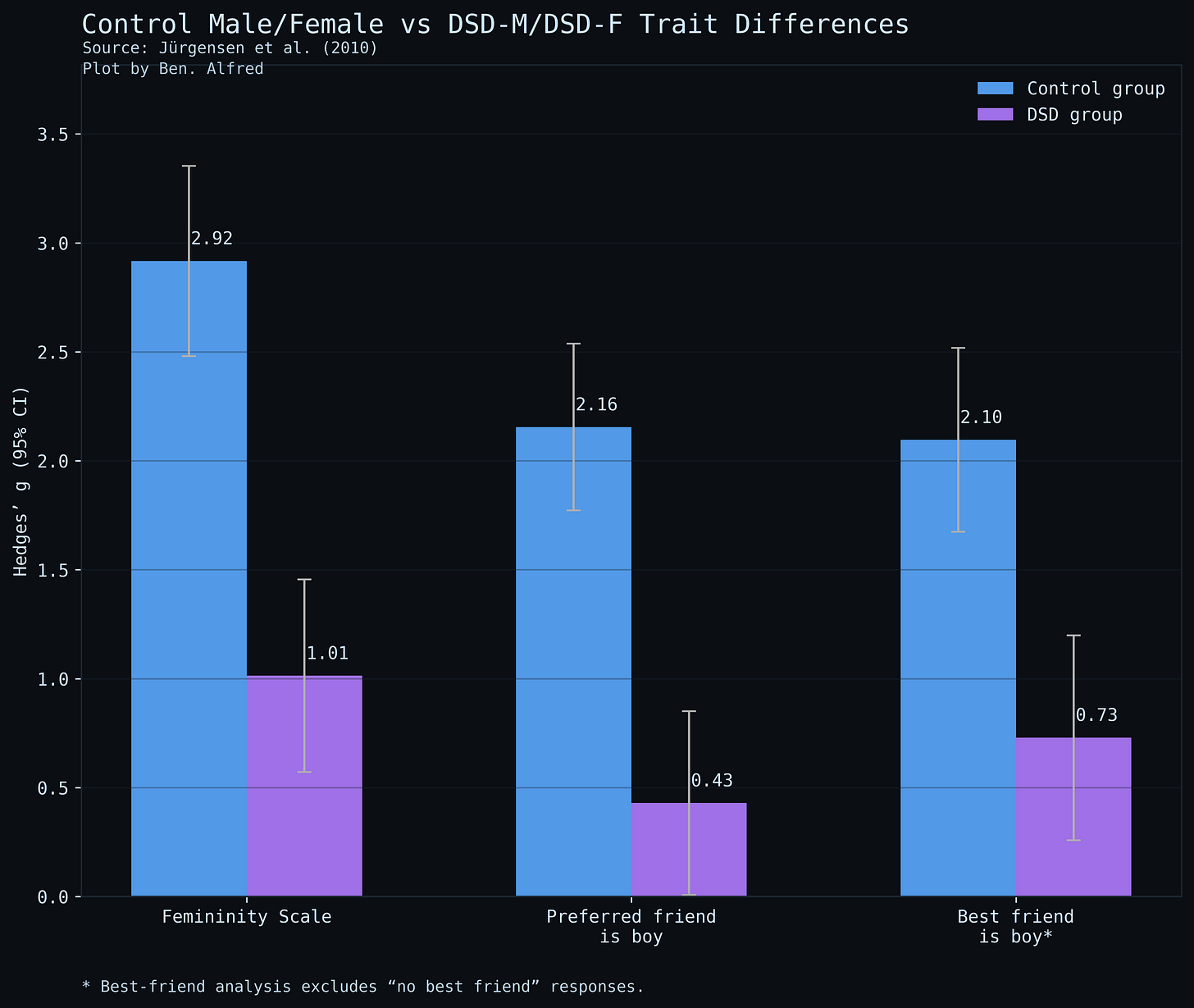

One such study was conducted by Jürgensen and colleagues (2010),2 based on a sample of 55 boys with DSD raised as males and 36 raised as females, as well as a control group of physiologically normal girls and boys. These groups were compared on a few measures: a femininity scale, the portion who would prefer a friend of a given sex, and the portion whose best friends are of a certain sex. The first measure is a shortened, German version of a popular scale called the CBAQ. The items are answered by the children’s parents and include, “He (she) plays with girl-type dolls such as baby or Barbie dolls” and “He (she) plays house”.3

The figure below, made graciously by Ben Alfred, converts the data for these four groups into two effect sizes.4 The numbers represent the standard deviation difference between, first, the males and females in the control group, and, second, the two different DSD groups. The former tells us how large the combined effect of nature and nurture is, while the second represents only the effect of nurture. If the phenomenon of girls playing with dolls and boys playing with cars is entirely explained by how children are reared, then the differences should be equal. On the other hand, if the phenomenon is entirely natural, then the second difference should be zero.

As you can see, the confidence intervals for the control and DSD comparisons never touch, showing that rearing cannot explain the entire difference. Yet the confidence intervals for the DSD comparisons also never touch zero, meaning that nature likewise cannot explain the entire difference.5 The ratio of the DSD d to the control d ranges from about 1:3 to 1:5, implying that nature explains much more of the overall sex gap on these measures than does nurture.

Conclusion

Most people agree that almost all the largest sex differences—height, criminality, personality—are at least partially innate. However, there are certain seemingly arbitrary differences between the sexes, such as which color they prefer, or what toys they play with. Why can’t boys wear pink? Why can’t girls play with Hot Wheels? The answer, they assume, is entirely cultural.

But the evidence I have reviews shows that this cannot be true. Both how children are reared and their innate attributes determine what toys they play with, and nature appears to be much more important than nurture!

Aaron Dymarskiy is an independent writer who does research on psychometrics, economics and history. He is co-owner of Heretical Insights and can be found on Twitter.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

References

Berenbaum, S. & Hines, M. (1992). Early androgens are related to childhood sex-typed toy preferences. Psychological Science, 3(3), 203-206.

Berenbaum, S. & Snyder, E. (1995). Early hormonal influences on childhood sex-typed activity and playmate preferences: Implications for the development of sexual orientation. Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 31-42.

Jürgensen, M., Hiort, O., Holterhus, P., & Thyen, U. (2007). Gender role behavior in children with XY karyotype and disorders of sex development. Hormones and Behavior, 51(3), 443-453.

Jürgensen, M., Kleinemeier, E., Lux, A., Steensma, T. D., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Hiort, O., Thyen, U., & DSD Network Working Group (2010). Psychosexual development in children with disorder of sex development (DSD) – results from the German Clinical Evaluation Study. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism : JPEM, 23(6), 565–578.

Laplante, L. & Delaney, S. (2020). Male mate choice for a female ornament in a monogamous cichlid fish, Mikrogeophagus ramirezi. Journal of Fish Biology, 96(3), 663-668.

Lonsdorf, E. (2017). Sex differences in nonhuman primate behavioral development. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95(1-2), 213-221.

Meyer-Bahlburg, H., Dolezal, C., Baker, S., Carlson, A., Obeid, J., & New, M. (2004). Prenatal Androgenization Affects Gender-Related Behavior But Not Gender Identity in 5–12-year-Old Girls with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(2), 97-104.

Neufeld, S., Collaer, M., Spencer, D., Pasterski, V., Hindmarsh, P., Hughes, L., Acerini, C., & Hines, M. (2023). Androgens and child behavior: Color and toy preferences in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Hormones and Behavior, 149, 105310.

Nordenström, A., Servin, A., Bohlin, G., Larrsson, A., & Wedell, A. (2002). Sex-Typed Toy Play Behavior Correlates with the Degree of Prenatal Androgen Exposure Assessed by CYP21 Genotype in Girls with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology, & Metabolism, 87(11), 5119-5124.

Pasterski, V., Geffner, M., Brain, C., Hindmarsh, P., Brook, C., & Hines, M. (2005). Prenatal Hormones and Postnatal Socialization by Parents as Determinants of Male-Typical Toy Play in Girls With Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. Child Development, 76(1), 264-278.

For those not in the know, autogynephilia is a paraphilia in which a man is attracted to himself as a woman; that is, he is in some vague sense aroused by the idea of himself being or becoming the other sex, or sometimes simply of dressing or acting as the other sex. Bailey is infamous for defending the belief that there are two major types of (biologically) male transgenders—those who were effeminate growing up and are attracted to men as adolescents or adults; and those who have autogynephilia.

This study also had a sample of girls with DSD, which consisted almost entirely (61 of 62) of those with CAH. They were able to replicate the finding of the studies reviewed in the previous section, finding a significantly lower femininity score (p < 0.05) in the CAH group. I did not include this study in that section because its methodology is too different from the others. Note that all of these girls were raised as their sex. This is because CAH, while being a DSD, does not make females look like boys.

The figures for the probability of having a female best friend, or the probability of preferring a female best friend, are not presented. The control d to DSD d ratios for these are essentially the same as for the probability of having a male best friend or preferring a male best friend.

For the preferred friend measure, the d is just barely significant.

See also the story of David Reimer who suffered a botched circumcision that left him castrated. They tried to give him a fake vagina as a teen but he rebelled and grew up to be a manly. Sadly, he killed himself.

Boys used to wear pink in the West because it was the boy version of the adult military red. And girls wore blue. Today, it's reversed, and it suggests that boys like "Amanda" choose the preferences of other contemporary boys that they identify with. I.e., the preference is cultural but not arbitrary.