Good Schools or Good Genes?

A look at whether selective schools actually boost students' grades.

Written by George Francis.

Toward the end of the Second World War, Britain engaged in a radical educational experiment. The all-party war coalition produced the 1944 Education Act creating “grammar schools,” state-run selective schools to take in all children in the top 25% of academic ability at age 11. Twenty years later, the experiment would be over. The then Labour Government demanded that grammar schools be converted into “state comprehensives” with no selective admissions. In 1970, Education Minister Margaret Thatcher declared that no more conversions were necessary but that no more grammar schools could be built either. A small number of grammar schools have survived in limbo, mainly in Northern Ireland and the Home Counties of Southern England.

The debate over grammar schools has always been divisive. Sir Anthony Crosland, who ordered their closure, once told his wife, “If it’s the last thing I do, I’m going to destroy every fucking grammar school in England.” And more recently, journalist Peter Hitchens vilified the enemies of grammar schools as “fanatical utopians.”

What makes the debate so fierce is that it strikes at the heart of a core political conflict: egalitarianism versus meritocracy—equality or equality of opportunity? In fact, the term “meritocracy” itself was created in the debate over British grammar schools. It arose as the title of Dr Michael Young’s 1958 satire attacking the grammar school system and IQ testing in general.

The idea of selective schooling in England arose from the Government’s 1924 Hadow report on “Psychological tests of educable capacity and their possible use in the public system of education.” It was written with the consultation and influence of Sir Charles Spearman and Sir Cyril Burt, two infamous scientists who respectively discovered the existence of ‘general intelligence’ and demonstrated that it was highly heritable.

The meritocratic proponents of grammar schools believe that separating children by ability allows for a more tailored education, promoting social mobility and human flourishing. By contrast, the egalitarians believe the system is unfair, providing elite schooling to those already born lucky, whether by genetics or environment, at the expense of everyone else.

That this debate provokes great fervor on both sides is understandable, but we should strive to get beyond this to examine the facts dispassionately. How much do grammar schools raise educational standards? How much do grammar schools promote social mobility? Which side of the debate is more accurate in its claims?

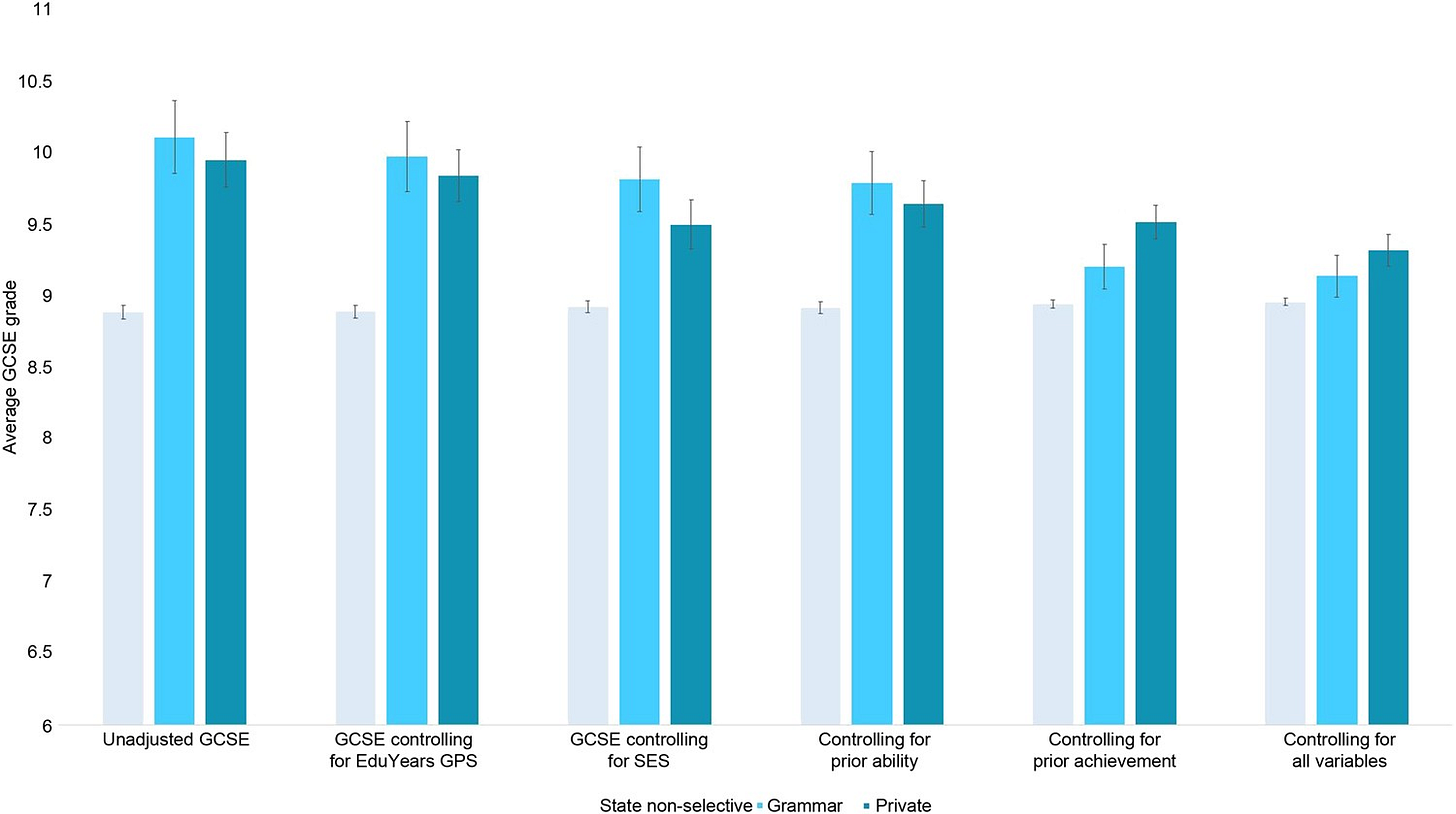

Let’s start with the key claim of grammar school proponents that they boost educational standards and attainment. Grammar schools do get better results compared to non-selective state schools, known as comprehensives. Grammar school grades in GCSE exams are around 1.2 standard deviations higher on average, equivalent to the scores of those in the 85th percentile. However, grammar schools also select the best students. What we want to know is whether grammar school students perform better than expected after accounting for prior abilities.

One approach is to use multivariate regression to determine whether going to grammar school predicts higher grades than what is predicted from one’s primary school grades. There are many of these analyses. One example is the 2008 report by the educational charity Sutton Trust. Their main result found that when grades in primary school (Key Stage 2) were controlled for, grammar school children scored half a grade higher at age 16 in the GCSE exam.

So should we conclude that grammar schools work? Not so fast. There is an important problem with the methodology. So long as the tests used by grammar schools provide additional information about the child’s intelligence, we would expect students who get in to outperform students who don’t with the same Key Stage 2 scores. The problem is made severe by the ‘low ceiling’ of the Key Stage 2 test. Historically, for each subject, around 25% of primary school students achieved the highest grade of 5 in Mathematics, Reading, and Writing. Many students could achieve level 5 in Key Stage 2 and would still be much less intelligent than the students who get into grammar schools.

We need to control for more and better indicators of prior ability. A 2018 paper did just that. It was produced by scientists at Kings College London and Toby Young, the son of Michael. They controlled for measures of prior ability, socioeconomic status, and even a genetic estimate of the student’s intelligence. They found that studying at a grammar school instead of a comprehensive resulted in a grade increase of 0.18 standard deviations, equivalent to moving from the 50th percentile to the 57th percentile.

We might still wonder whether these statistical controls are really good enough. So long as the grammar school’s tests tell them something more than family background and prior ability, we should still expect their students to perform better. To solve the issue, we need the gold standard of scientific inference — the randomized control trial.

If borderline students were randomly assigned to a comprehensive school or a grammar school, we could then know for certain if there really was an effect. And yet, despite the fiery debate over grammar schools, nobody has conducted such a rigorous experiment. The best comparisons we have are from experiments randomly giving parents vouchers for private schooling. Private schools will typically attract more able students, making them like grammar schools. Whilst these studies have shown success in the developing world, in the United States, it is estimated that going to a private school only increases grades by 0.028 standard deviations, equivalent to going from the 50th to the 51st percentile.

When the most rigorous statistical tests are used, moving into elite schooling does not seem to matter much for grades. It seems very unlikely that grammar schools, as they exist today, lead to better outcomes. This may not have always been the case. At least prior to 1964, grammar schools trained their students for a more thorough curriculum and tough examinations compared to what was taught in other government schools. However, so long as they are teaching the same curriculum, it is unlikely that the selective nature of grammar schools helps their students to learn much more.

Perhaps grammar schools provide social mobility even if they do not deliver better grades? Going to an elite school can teach you etiquette and give you a middle-upper-class social network that can help in the job market. Placing talented working-class students in this environment could help them better realize their potential.

Because of the staggered conversion of grammar schools into comprehensives across time and also across geography, some economists attempted to identify whether these conversions were associated with lower mobility or not. The authors used census data for 90,000 individuals, which record their occupation and their parent’s occupation. The stronger parental occupation predicts the occupational status of the child, the less relative social mobility. The authors then measured exposure to the grammar school system with a “selectivity index” representing the proportion of students in the local area attending the selective system.

So what did the authors find? Across time and local authorities, there was no relationship between the selectivity index and social mobility. Perhaps the social network was not so useful after all?

The meritocratic ideal of grammar schools certainly is charmingly romantic. The rags-to-riches story of working-class lads being given the opportunity to use their talents to great personal and public success is certainly desirable. But in practice, and whilst the research is far from ideal, the evidence that grammar schools are meritocratic is weak.

Perhaps, if some better studies were run, randomizing which marginal students get in, we would finally know for sure whether grammar schools matter. Then we could end the grammar school limbo, building more of them or shutting the remaining schools down. But then again, if it really were just a technical question of grades and mobility, surely we would have solved it by now?

Perhaps the grammar school debate was never about social mobility after all. Beneath the veneer of ‘meritocracy’ lies an ugly truth of the debate over grammar schools — classism. The middle class wants to avoid sending their children to school with the troublesome and dull. And those who cannot get into a grammar school hardly think it fair that their schools are not so nice. Certainly many claim to believe in ‘solidarity’ — we should mix all the classes together or at least make the rich pay to send their children to private schools. Yet when it comes to the schooling of their own children, the virtuous many become shameless elitists.

This article was originally published on Aporia in March of last year. We’re republishing it because it’s one of our favourites.

George Francis is a writer and social scientist interested in intelligence and economics. If you like deep data dives, check out his Substack Anglo Reaction. Find him on Twitter here.

Support Aporia with a $6 monthly subscription and follow us on Twitter.

"At least prior to 1964, grammar schools trained their students for a more thorough curriculum and tough examinations compared to what was taught in other government schools. However, so long as they are teaching the same curriculum, it is unlikely that the selective nature of grammar schools helps their students to learn much more. "

This caveat more or less makes the rest of the article moot. True, selective schools are not a magic bullet, but they are precondition for doing anything better. You might as well say that if Google put potential employees through the same selection process as McDonalds it would be fine so long as employees at both companies performed the same tasks. Technically true, but so what?

One important point also missed by the article is that, originally, comprehensives were also not supposed to internally stream pupils by ability. This is logical if you believe that mixing up pupils of different ability levels has some sort of positive effect: you can only achieve this effect by putting pupils in the same class, not merely the same institution. However, this was abandoned in nearly every comprehensive school within a decade because trying to teach mixed ability classes of 15 year olds Mathematics is crazy and a complete waste of time. In fact, the GCSE system has for decades had two tracks (Higher and Foundation). The 'Comprehensive' school I went to was, for all academic purposes, two schools in one building. We socialised with the thick kids at break to the extent that we wanted to, and we had mixed ability classes for History and Geography and other subjects that didn't matter much, but that was it. Abolishing grammar schools was thus an incredibly expensive and disruptive way of getting kids from Grammar schools and Secondary Moderns to share breaktime and make History lessons into a joke.

This essay clearly represents a lot of work so I am reluctant to be dismissive. But there is a but....and it's a big one. Anyone reading this without knowledge of its broader context would get a seriously distorted picture of post-war British schooling. The reality is that it has been bedevilled by an endless stream of sub-egalitarian theorising that has been 100% counter-productive. This theorising has pumped out from the utopian petri-dishes of academe and - via teacher training colleges and local authority education bureaucracies - into the school system. I have some experience of this but a comment thread is not a place to discuss the full extent and depth of the tragedy of it. Anyone who wants to go there should read Melanie Philips' All Must Have Prizes (1996), Just one for-instance....in the 1980s education 'experts' deemed that pupils filling in multiple-choice tick boxes was a valid substitute for them showing their learning in sentence form.