Externalities from low-skilled migration

A response to Bryan Caplan and Richard Hanania.

Written by Alden Whitfeld.

Richard Hanania recently posted the following on Twitter:

Why are Japanese manual laborers and low wage workers so competent? As Bryan Caplan points out, they’re massively overqualified! The lack of immigration means natives work worse jobs. The world works in the exact opposite way nativists think.

Put aside the fact that most immigration restrictionists would be delighted with Japan’s immigration policy. Hanania, Caplan and other advocates of mass immigration aren’t the first to make this sort of argument. In fact, it’s a talking point that’s been repeated dozens of times.

Ask any economist why mass immigration is good for a country, and if they’re honest they’ll admit the fiscal impact is mixed and “it’s complicated”. Once you start getting into all the other issues like individual versus household level accounting1, the cost of housing in cities, negative effects on wages2, conflating GDP growth with economic gains to natives and country-of-origin effects, the typical mainstream economist will retreat to their last stand: abstract economic models, long-run “what-ifs”, and elegant equations where immigration magically boosts national prosperity through indirect channels.

The argument for mass immigration goes something like this: even if immigrants raise the cost of housing, compete with native workers and strain the welfare system, they still make the economy more “dynamic”. Specifically, they free up high-skilled natives to focus on more complex work, boosting economic growth through specialization of labor.

This isn’t necessarily untrue. However, the magnitude of the complementary gains must be fairly modest given that native-born Americans are well-represented in all occupations, including ones that people often consider “immigrant jobs”. Consider these statistics compiled by Jason Richwine:

Of the 525 civilian occupations identified in Census Bureau data, only five are majority immigrant (either legal or illegal) — with just one, “manicurists and pedicurists”, exceeding 60 percent.

The five majority-immigrant occupations account for only 0.6 percent of the civilian U.S. workforce. Moreover, native-born Americans still comprise 40 percent of workers in these occupations.

Many occupations often thought to be overwhelmingly foreign-born are in fact majority native-born:

Maids and housekeepers: 51 percent native

Construction laborers: 61 percent native

Home health aides: 61 percent native

Landscaping workers: 66 percent native

Janitors: 71 percent native

About half of agricultural workers are immigrants, but all agricultural workers — natives and immigrants together — constitute less than 1 percent of the U.S. workforce.

There are 65 occupations in which 25 percent or more of the workers are immigrants. However, these occupations are still held by about one in every nine native-born workers — 16 million natives in total.

So yes, low-skilled immigrants may complement natives, though not by very much. That’s not the end of the story, however. Hanania and Caplan weren’t talking about the United States, but Japan—a country with very few immigrants.3 Complementary effects would surely be larger in Japan, making their argument more sensible?

Not really. The truth is that even this is being charitable. While some specialization may occur, the negative externalities imposed by low-skilled immigration overwhelm the modest benefits it may confer.

Individuals with high IQs generate positive externalities for their fellow citizens: less criminality, more cooperation, greater trust (which leads to less demand for government regulations) and higher economic literacy. Indeed, national IQ is positively correlated with almost everything good and negatively correlated with almost everything bad. We therefore shouldn’t be surprised that it’s the single best predictor of economic growth and also an excellent predictor of socioeconomic development.

In fact, after correcting individual IQ, income and wealth for measurement error, the correlation between national IQ and GDP per capita remains stronger than the one between individual IQ and income.

In societies created by individuals with high IQs, even those of unexceptional ability are more productive. You see this dynamic in the wage trajectories of immigrants themselves. Immigrants who move from low-income, low-productivity countries to wealthy, Western countries see sharp increases in their wages. It is unlikely that this is due to substantial improvements in the immigrants’ own abilities.

The totality of the evidence suggests that race differences in IQ are poorly explained by environmental differences, and there is large regression toward the mean in the second generation. Lutz Hendricks and Todd Schoellman have estimated that the average wage gain at migration is 38% of the gap in GDP per worker—so 38% of cross-country income differences are attributable to differences in physical capital and total factor productivity. These latter differences are mostly caused by national IQ. In other words, it’s the host country’s higher average intelligence that makes the migrants who move there more productive.

Insofar as low-skilled immigrants lower the national IQ of the host society, they generate negative externalities for their fellow citizens. Any gains from specialization of labour are almost certainly offset by these externalities. If moving to a high-IQ country raises one’s living standards independently of one’s own ability, the reverse should also be true—that the same person living in a country with a lower IQ should have lower living standards.

This seems consistent with the obvious fact that immigrants are very eager to move to countries with higher human capital but not to those with lower human capital. If the benefits of specialization for two groups of different average ability are so large, such that moving to a lower-IQ country would actually make one richer because “higher IQ would be in greater demand”, it is strange that Westerners don’t take advantage of this by moving to South Asia or SubSaharan Africa en masse. Of course, economic activity doesn’t take place in a vacuum, and indirect effects go both ways. Actual human behavior suggests that the costs of lower average IQ greatly outweigh the benefits.

And this is assuming that the “freeing up” of native workers is actually a good thing in the long run. Native workers displaced by immigrants who go apply for a higher-skilled job will be less skilled than the people who are currently working in that job—which is of course bad from the standpoint of the job’s productivity.

According to Bryan Caplan himself, employers are terrible at discovering the productivity of workers, so productivity falls are by no means implausible. Consider an experiment which looked at the ability of technical recruiters to predict a candidate’s interview performance from their resumé. The twist was that the candidates whose resumés were used in the experiment had already participated in several mock interviews, so their actual performance was already known and scored. So, how did recruiter predictions fare? As it turns out, barely better than chance:

Immigrants also have cultural effects on the host society. The reality is that assimilation is largely a myth, differences between immigrants and natives are persistent, and the life trajectories of immigrants in the second generation are similar to those in the first. An easy way to illustrate the importance of cultural persistence is with the example of corruption (which everyone agrees is bad for economic growth).

Alberto Simpser looked at various immigrant groups from Europe and their children, obtaining two key results. Second generation European immigrants clearly resemble their home countries when it comes to their tolerance towards bribery, even when controlling for many factors. And tolerance towards bribery does indeed translate into offering and taking bribes. The takeaway here is that admitting low-skilled immigrants from corrupt countries will increase the amount of corruption in the West.

Slavery in the American South lowered productivity by reducing the need for labour-saving technology. Similar dynamics may be at work in sectors that rely on cheap labour today. The agricultural sector is one where immigration proponents often like to claim that migrant labor is absolutely essential. Yet relying on migrant labour may be falling into the same trap as slavery.

Ran Abramitzky and colleagues examined the labour market effects of the 1920s immigration restrictions in the U.S., and found that they caused an inflow of rural Americans into cities. How did farmers compensate for the loss of workers? They shifted toward capital-intensive agriculture—in other words, they mechanized. That was the 1920s, so what about today? It’s highly plausible that dependence on migrant labor disincentivizes automation. Katja Mann and Dario Pozzoli analysed changes in the share of non-Western immigrants in the local workforce across Danish municipalities. Controlling for a large number of factors, they found that the share of non-Western migrants was negatively correlated with robot adoptions.

Specifically, they found that “a one percentage point increase in the share of non-Western migrants decreases the probability of robot adoption by 12%” which “supports the substitution hypothesis”. Immigration delays the moment when firms must adapt, invest and modernize. This may look like stability in the short run, but it’s stagnation in the long run.

Is low-skilled immigration good for the economy? There may be some complementarities here and there. Perhaps doctors can see a few more patients because somewhere out there a migrant worker is picking tomatoes. Yet this view is fundamentally short-sighted. You can import labor, but you will also be importing a lot of other things besides the labor itself, most of which you want less of—not more. So even if some indirect benefits do exist, all the indirect costs easily outweigh them.

A slightly different version of this article was originally published here.

Alden Whitfeld is an independent writer who does research on immigration and politics. He is co-owner of the blog Heretical Insights and can be found on Twitter.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

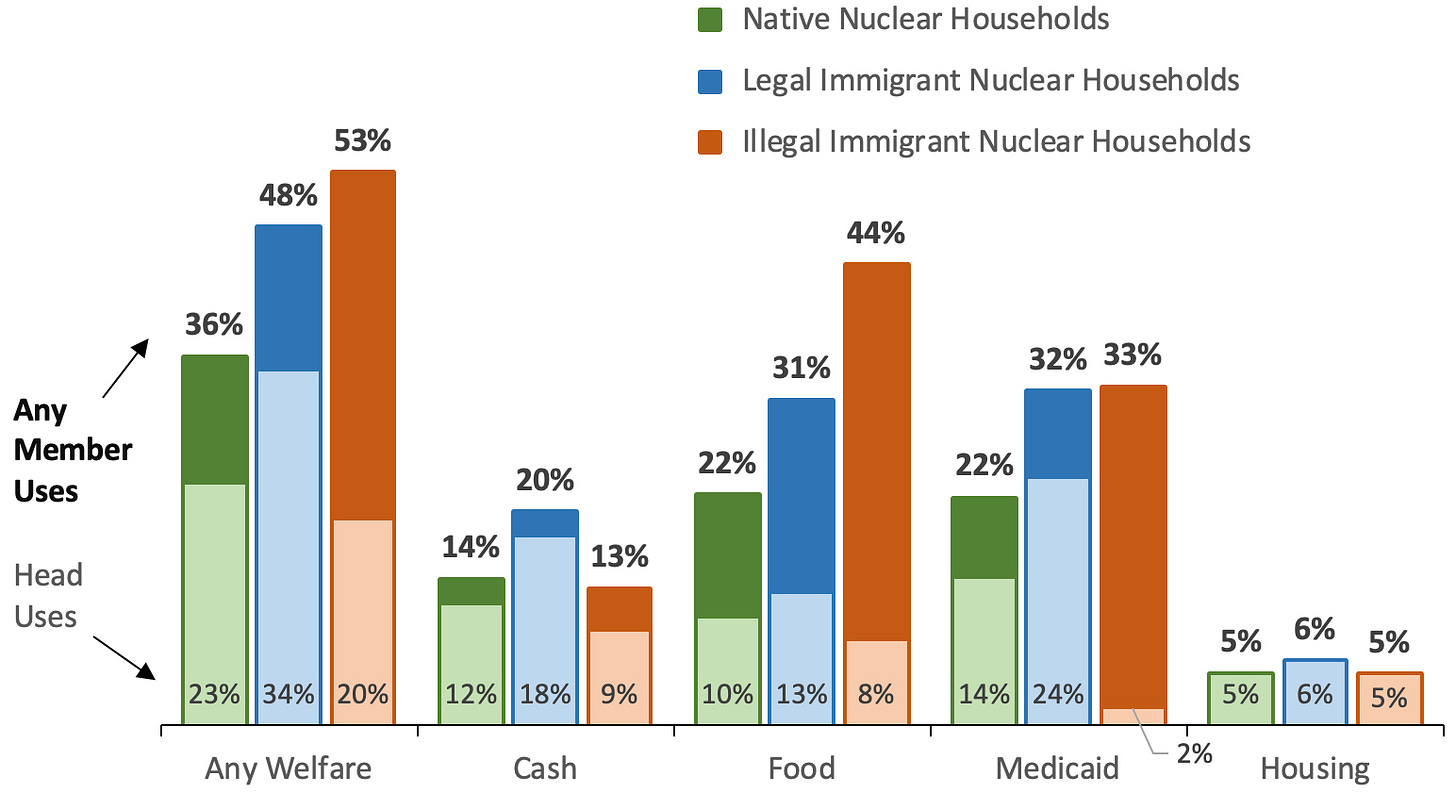

Much of the welfare debate comes down to whether analyses should be conducted at the household level or the individual level. The reason households are preferable stems from the fact that there are, at least in theory, restrictions imposed on the ability of new arrivals to access welfare programs. Their children, who are legally natives, do not face such restrictions. Hence if immigrants are getting access to welfare programs via their children, individual level analyses will count this as an expense on the part of natives—even though this is completely wrong. Here’s Richwine:

For an illustration, consider an illegal immigrant head of household who is not herself enrolled in Medicaid but who does enroll her U.S.-born children. The household-level approach correctly concludes that this is a case of an illegal immigrant accessing welfare. After all, a parent is legally obligated to provide medical care for her children. If she does not, and the taxpayers step in to do it for her, then the parent receives a financial benefit. By contrast, the individual-level approach would assign welfare strictly to the U.S.-born children in this example. It would see only native consumption of welfare, with the illegal immigrant mother treated as self-reliant. That view is divorced from reality.

When looking at nuclear family households, we can see that a large percentage of their welfare is being consumed by someone other than the household head. What’s more, this trend is more pronounced for illegal immigrant households than for legal ones, demonstrating how misleading the results from individual level analyses are:

The fact that the children are legally natives is irrelevant because that’s just a function of existing laws in the United States. Calling the children “natives” doesn’t change the fact that they are an expense that only arose because their parents were allowed into the country in the first place (or entered illegally). They should obviously be placed in the immigrant category for a fair comparison.

It is true that the literature on immigration and wages is hotly debated. However, this is largely because so many studies on the topic are poorly done. Economists who do sensible things—such as account for the non-random settlement patterns of immigrants, the fact that natives relocate when immigrants arrive, the correlation between new arrivals and recovery from previous waves, and the effect of monopsonies—all agree that there is a negative impact. Eyeballing the effect sizes from these studies, 5–10% is a reasonable estimate for the wage reduction from a 10% increase in the share of immigrants.

Of course, since immigrants are settling in areas of high economic opportunity, the true effect is even larger because natives who get displaced move to areas with less economic opportunity, while the rewards for natives who do not wish to move are also reduced.

They would presumably argue that the same applies to the U.S.

“Calling the children “natives” doesn’t change the fact that they are an expense that only arose because their parents were allowed into the country in the first place”

Bingo. A couple of decades or so ago, I saw the CA stat’s for immigrants wrt to their current wages as low level manual laborers and the estimated expense of just two of their children attending public school in CA, K-12. Two children attending public school for 12 years was projected at that time to cost $300k and that was not including inflation projections. The typical (low) household income was well below any conceivable tax rate able to recoup such a taxpayer footed expense across even a lifetime of menial wage household income.

The knock on (beneficial) effects of such immigration is little more than wishful thinking. As “Realist” has succinctly noted, cost in $$$ pales to cost in IQ dilution of the nation. Those costs will live on forever and be subtly hidden.

Bryan Caplan and Richard Hanania like to see themselves as "scientists" in opposition to the irrational yahoos on the other side. A true scientist, however, first tests a new proposal on a small sample of consenting participants. The requirement of "consent" is critical. If there is no consent, the experiment cannot go ahead.

If the results are promising, a true scientist will then try to replicate the results with a larger sample. If the results are still good, the proposal is tentatively accepted — although it is still subject to review and criticism. In fact, criticism is always encouraged.

This approach has little in common with what people like Bryan Caplan and Richard Hanania are advocating. Where is the consent? Where is the preliminary testing on a small scale? And where is the freedom to criticize?