Written by Noah Carl and Bo Winegard.

With fertility stuck below replacement level in most of the developed world, people are scrambling to understand which factors raise birth rates and which factors lower them. In a recent article, Daniel Hess, better known by his Twitter alias “More Births”, argues that high population density is a major cause of low birth rates. His argument stands in contrast to the one made by Bryan Caplan in Build, Baby, Build, namely that building at high density has several benefits and need not come at the expense of childbearing.

Hess presents an enormous amount of evidence in his article, which we will do our best to summarise here:

Various academic studies have examined the relationship between population density and fertility across countries or other geographic areas, and every one has found that it is negative. What’s more, some of these studies claim the relationship is causal.

Looking at fertility maps for Western countries like Britain, France, Germany, the US and Japan, the level is invariably lowest in highly dense urban centres. There is a strong negative association between fertility and urbanisation across countries. And there is a negative association between fertility and percentage living in apartments across major Western cities.

Low levels of fertility in highly dense urban centres cannot be explained entirely or even mostly by selection of families into the suburbs. Nor can they be explained by the cost of housing.

Studies of other mammal species have found that fertility declines when population density reaches a certain level. This suggests there may be general biological mechanisms that suppress reproduction at high densities.

Many economists who advocate building at high densities chose to raise their own families in single-family homes. And economics tells us to trust people’s revealed preferences over their stated preferences.

Hess’s article is comprehensive and well-argued. However, we are not convinced by his claims. While population density may have a small negative effect on fertility, we suspect that much of the effect claimed by Hess is in fact due to selection. We therefore doubt that population density is a major cause of low birth rates, although it may be a minor one.

What is population density?

Several of the academic studies Hess cites are largely uninformative because they use the wrong measure of population density. Specifically, they use unweighted density: the number of people in a country divided by the total land area. The right measure to use is population-weighted density: the weighted average of the population densities in each square kilometre, with weights equal to the number of people within each square kilometre.

It may have occurred to you that people aren’t spread out evenly across a country. Rather, they are concentrated in settlements of varying sizes. So simply dividing a country’s population by its area doesn’t capture the level of density that people actually experience.

Here’s a map of Egypt showing where Egyptians live. As you can see, they are overwhelmingly concentrated along the river Nile. Despite having a large area, which is mostly desert, Egypt is one of the most densely populated countries on earth. It is in fact far more densely populated than nominally dense countries like the Netherlands. (Egypt has a TFR of 2.8, comfortably above the replacement level.)

A study Hess cites that uses the correct measure of population density is the one by David de la Croix and Paula Gobbi. This seems to be a well-done study, although the effect size is relatively small. According to the authors’ preferred estimate, a tenfold increase in population density lowers the fertility rate by 0.35 births per woman.

A tenfold increase is roughly equivalent to the difference between suburban England and inner London. Given that less than half of Britain’s population lives above the density of suburban England, the estimate implies that limiting Britain’s density to this level could increase the fertility rate by 0.5 × 0.35 = 0.18 births per woman. This is hardly going to solve the fertility crisis. In reality, achieving such a large reduction in density would be practically impossible.

A look at the evidence

We obtained data on population-weighted density and the TFR for a large sample of countries, as well as the 50 US states, in the year 2020.1 We used two separate measures of population-weighted density: one based on the arithmetic mean and one based on the geometric mean. These are strongly though imperfectly correlated.

The chart below shows the TFR’s relationship with each measure of population-weighted density in the full sample of countries. There is a moderate negative association when using the measure based on the geometric mean (r = –.41, p < 0.001). However, there is no association when using the measure based on the arithmetic mean (r = –.07, p = 0.3).

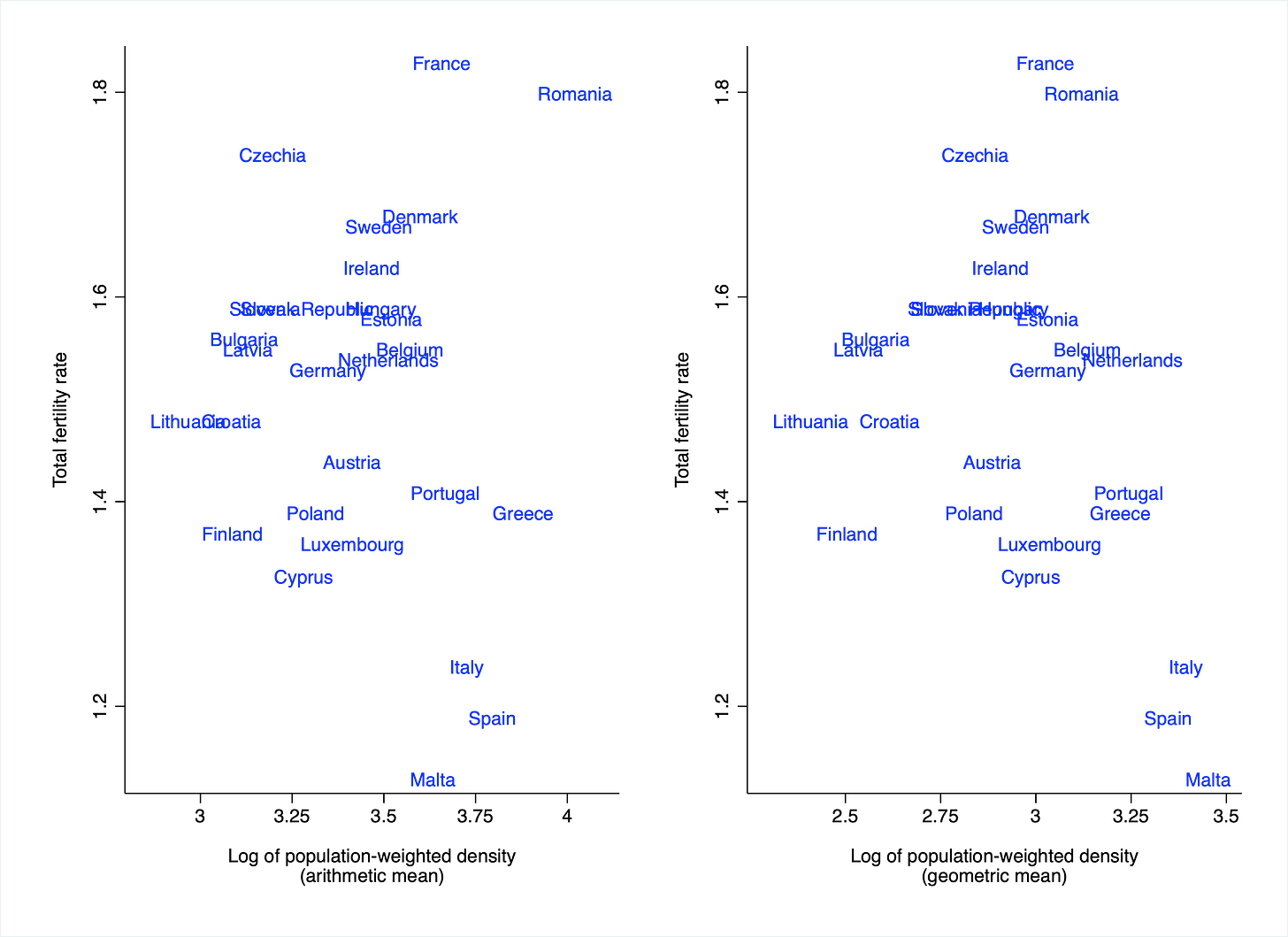

The next chart shows the TFR’s relationship with each measure of population-weighted density among the 27 EU member states. Although both correlations are negative, neither is strong (r ≤ –.34) and neither reaches statistical significance (p ≥ 0.08).

The next chart shows the TFR’s relationship with each measure of population-weighted density among the 50 US states. Both correlations are weak (r ≤ –.20) and neither reaches statistical significance (p ≥ 0.1).

The analyses provide little evidence that population density, measured properly, is strongly related to fertility: out of six correlations, only one is statistically significant. These weak correlations cannot be blamed on some general issue with predicting fertility. The TFR is highly correlated with log GDP per capita and female education across countries, and is highly correlated with Republican vote share across US states. It seems that population-weighted density is simply not a consistent predictor of the TFR.

Another way to test whether population density matters is to compare the fertility of culturally similar places that vary in terms of density.

The chart below shows TFRs in China and three Chinese cities states (Singapore, Hong Kong and Macao) for the period since 1950. While all four places have become denser over time, the three city states have always been much denser than China itself. Despite this, the four have similar fertility rates today and also had similar fertility rates in the 1950s (prior to the Great Leap Forward). Macao is ten times denser than China but its TFR is only 0.3 births per woman lower. Singapore is three times denser and has the same TFR.

The next chart shows TFRs in Monaco, France and Italy for the same period. Note that Monaco is a city state bordered by France and very close to Italy, with cultural influences from both. Only two square kilometres in size, it is the densest country in Europe by far and about six times denser than Italy. Despite this, it actually has a higher TFR than both of its neighbours. And before you point out that Monaco is filthy rich, remember that GDP per capita is negatively associated with fertility across countries.

One final point is that Western cities have always been dense, yet fertility was previously much higher. Simon Szreter and Anne Hardy report that marital fertility in London for women born 1871–1880 was 4.4 births per woman, compared to 4.5 in England as a whole. 19th-century London was much denser than the rest of the country and was even known for the problem of overcrowding. As the authors note, “the evidence flatly contradicts any strong or simple version of the hypothesis that ‘urbanisation’ was the primary cause of falling or low fertility”.2

Causal mechanisms

As Hess correctly points out, studies of other mammal species have found that fertility declines when population density reaches a certain level. However, the most plausible mechanism for this is unlikely to apply to humans except perhaps in extreme circumstances: elevated levels of stress hormones induce infertility by suppressing ovulation and/or obstructing implantation. While some women living in dense urban areas may suffer from stress-induced infertility, this is not an important contributor to low birth rates.

The reason birth rates are low in dense urban areas is that people are less likely to get married and then have fewer children when they do get married. It is not that women are infertile. As we noted above, fertility in Western cities was much higher in the past, which implies that high fertility is biologically compatible with high-density living.

Conclusion

We are not convinced by Hess’s argument that high population density is a major cause of low birth rates.

Several academic studies Hess cites are uninformative because they use the wrong measure of population density. One that is informative yields a small effect size. Population density is barely associated with fertility rates across US states or EU member states. Nor is it consistently associated with fertility across countries. Comparing culturally similar places that vary in terms of density suggests it has little or no effect. And in the 19th-century, London’s marital fertility rate was similar to that of England as a whole.

Why are fertility and population density often strongly associated within countries? We suspect the primary reason is that family-oriented people prefer to live in suburban or rural areas than in big cities.

Having said that, it is conceivable that very high population densities of the kind seen in Chinese city states are detrimental for fertility. Indeed, there exist only a handful of countries with population-weighted densities greater than 10,000 people per square kilometre that have TFRs above the replacement level.3 However, densities this high are rare. Only 6% of the EU’s population lives in regions with densities this high. So even if very high densities do suppress fertility, the scope for boosting fertility by building at lower densities is rather limited.

Noah Carl and Bo Winegard are the Editors of Aporia.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

We redid our analysis using the 2019 TFR to eliminate possible pandemic effects. The results were essentially identical.

Non-marital fertility may have been somewhat lower in London. Yet Szreter and Hardy point out that “illegitimate fertility was generally remarkably low throughout the British Isles”.

Using the measure of population-weighted density based on the arithmetic mean, Monaco, Egypt, Lebanon and Angola all have TFRs ≥ 2.1.

Historically, cities were often population sinks due to higher disease rates, not low fertility. Diseases can increase death rates, but there's nothing about cities that causes lower fertility rates.

If density lowered fertility rates, then the Ashkenazi Jews would've gone extinct in the 1800s. Instead, the Jews had a huge population explosion in the 19th century, while mostly living in European cities. In many cases, the increasing Jewish population in cities lead to overcrowding in urban areas, hence one reason why antisemitism was rapidly growing.

When I have time, I'll add a new section to my FAQs to address this topic in greater depth, since I surprisingly haven't covered it yet. I'll make sure there's a link to this article, once I finish it. https://zerocontradictions.net/faqs/overpopulation

The pearl clutching about the causes and solutions to declining birth rates is a waste of time. Now that we've moved beyond agricultural subsistence economies, low birth rates are inevitable -- and permanent. Nobody needs 10 kids to bring in the yam harvest any more.

Urban density, feminism, the Internet perhaps all contribute but I would submit it's a more fruitful use of research dollars to figure out how to reconfigure society to function with fewer people via automation, robotics, AI, etc. We're already moving in that direction, so this is a challenge that can be met.

The global population in 1970 was 3.7 billion, less than half of what it is today. Was it a dystopian hellscape then? No.

If we can manage the decline responsibly, a reduction in population would result in a profound increase in quality of life for all, not to mention reducing resource utilization to more sane levels.

Projections show we have until 2080, when global population finally begins to fall. That's doable, if we have our priorities straight.