Diversity Really Isn't Our Strength

Noah Carl compares GDP per capita in the US and Western Europe over time to examine the effect of diversity.

Written by Noah Carl.

In his recent article ‘Diversity Really is Our Strength’, Richard Hanania noted that “ethnolinguistic diversity seems to be common among overperformers” (among countries that have a higher GDP per capita than you’d expect based on their average IQ). Emil Kirkegaard went about testing this hypothesis.

He looked at the effect of ethnic fractionalisation on measures of economic freedom and national income when controlling for average IQ, and found that most of the estimates were not significantly different from zero. There was little evidence that ethnolinguistic diversity is beneficial for growth.

Yet Hanania was not convinced. “You found a null result,” he argued, “but if you found a real result in either direction, it wouldn’t have meant anything” because “it’s a bad measure.” What’s more, the analysis was “underpowered” and there were “too many lurking variables”. (This is despite the fact that Hanania used a simple scatterplot as evidence in his own article.)

Let’s suppose he’s right: ethnic fractionalisation is a bad measure and there were too many lurking variables in Kirkegaard’s analysis. Is there any other way to tackle this question?

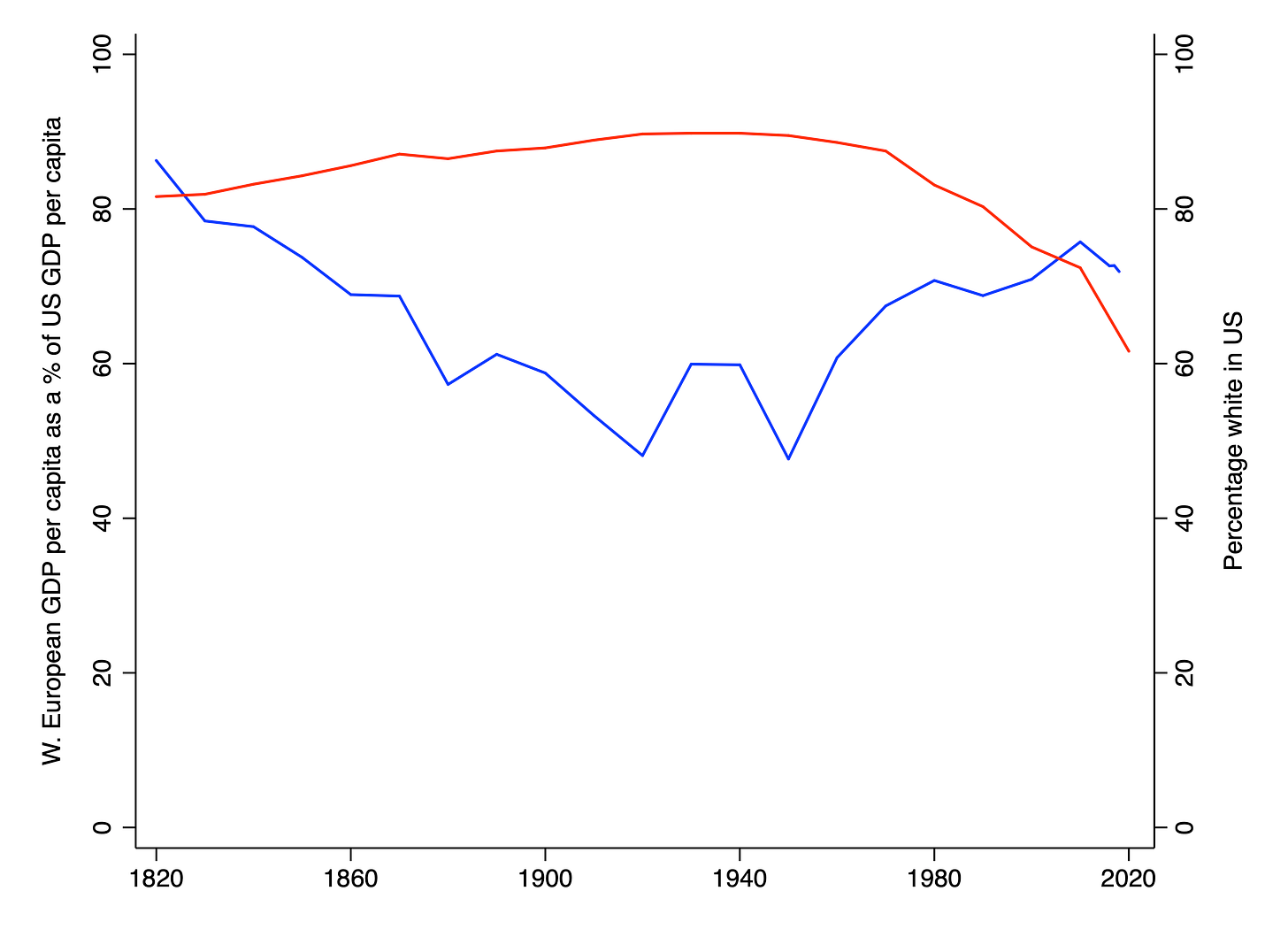

One is to compare GDP per capita in the US and Western Europe over time. If Hanania is right, the gap should be largest when the US was most diverse and smallest when it was least diverse. (Thanks to commenter Guy Incognito for giving me this idea.)

Historical data on GDP per capita were obtained from the latest version of the Maddison database. And to track diversity, I used the simplest possible measure: the percentage of the population that is non-Hispanic white, as reported by the US census. The results are shown below.

The first thing to notice is that the US has been richer than Western Europe for all of the last two centuries. (Although individual countries like Britain and the Netherlands were richer than the US during the 19th century, western Europe as a whole was not.) In 1820, western Europe’s GDP per capita was 86% of America’s, and the US population was 82% white.

Over the next century, the US grew much faster, so that by the late 1920s, Western Europe’s GDP per capita was less than 50% of America’s. During this period, the white population share trended upward – reaching a maximum of 90% in 1930.

Then came the great depression, which hit America harder than Europe – leading to a sharp rise in Western Europe’s GDP per capita as a percentage of America’s. This was followed by the Second World War, which obviously hit Europe harder – reversing the gains made during the great depression. During this period, the white population share remained around 90%.

After the Second World War, western Europe grew faster than the US – substantially narrowing the gap in GDP per capita over the next three decades. Meanwhile, the white population share trended downward, rapidly so after the 1965 Immigration Act.

Since 1980, western Europe’s GDP per capita has remained roughly constant as a share of America’s at around 70%. The white population share has continued to fall, reaching 62% in 2020.

There are several caveats, but what the chart clearly shows is an inverse relationship: America was relatively richer when it was less diverse and relatively poorer when it was more diverse. This is particularly evident in the post-war period, where we can assume the data is of higher quality. As the white population share fell, Western Europe caught up in terms of GDP per capita.

The first major caveat is that the white population share is an imperfect measure of diversity. After all, the European immigrants who came to the US between 1850 and 1920 were quite diverse (in the original sense of that term). There were Irish, Italians, Eastern Europeans, etc. And they did not initially enjoy the same status as the white Americans who were already there.

So even though the population became whiter between 1880 and 1920, you could argue that it became more diverse. (Today, of course, those different groups of Europeans would not be considered “diverse”.) This illustrates one of the problems with discussing the impact of diversity: it doesn’t always mean the same thing.

Having said that, European immigrants to the US were well-assimilated by the 1950s, and it was at this time that the US was richest relative to Western Europe.

Another major caveat is that Western Europe has also been getting more diverse, but this isn’t factored into the analysis. Since several countries (like France) don’t collect data on race and ethnicity, it is not possible to plot the region’s white population share over time. But we can say that most of the change has occurred since 1990. The UK, for example, was 95% white in the 1991 census.

If data were available for Western Europe, it could be taken into account by plotting the difference between the white population share of Western Europe and the white population share of the US. This would look much like the red line in the chart above, except that the decrease would be somewhat shallower, especially for the last three decades.

I would not claim the preceding analysis provides much evidence that diversity is bad for growth: there are various reasons why America’s GDP per capita has changed relative to Western Europe’s, and diversity is probably not the most important one. However, it provides no evidence that diversity is good for growth – which is what Hanania initially claimed.

Noah Carl is an independent writer and researcher. You can follow him on Twitter here and subscribe to his Substack newsletter here.

In one sense, this analysis would support RH's position because it was when America achieved (word chosen advisedly) its lowest level of diversity (1930s - 1965) that it experienced its biggest growth in the welfare state and government spending, which then stalled after the post-1965 growth of diversity.

RH's argument is simultaneously crazy, evil, and retarded. Crazy because it is denies the most obvious thing in the world, namely that importing immigrants from country X makes your country resemble country X more. Evil, because it proposes using immigration as a democracy hack, crashing social trust in order to trick ethnocentric voters into voting for free market policies . Retarded, because it attributes wildly outsized effects of different welfare state models on economic growth. However, one premise is true: countries with diversity are unlikely to become competently governed social democracies, which for Lolbertarian techbros is the worst fate imaginable.

And then there's that other kind of 'diversity'... the West's obsession with 'identity'. Heather Mac Donald's The Diversity Delusion provides chilling evidence of how this is harming the West's competitiveness in science and technology: ”A study by the American Association for the Advancement of Science found “systemic anti-LGBTQ bias within STEM industry and academia.” HM comments dryly that “somehow NSF-backed scientists managed to rack up more than two hundred Nobel prizes before the agency realised that scientific progress depends on ‘diversity’. Meanwhile, “driven by unapologetic meritocracy, China is catching up to the United States in science and technology. Identity politics in American science is a political self-indulgence we cannot afford.”

I reviewed The Diversity Delusion here: https://grahamcunningham.substack.com/p/how-diversity-narrows-the-mind