Written by Alden Whitfeld.

Across developed nations, few topics unite public opinion quite like hostility toward China. In the United States, dislike of China cuts cleanly across demographic groups—political affiliations, age brackets and levels of education. Even Chinese Americans tend to view the country unfavorably. It is one of the few bipartisan reflexes left in American life.

This hostility takes many forms. In the media, China is repeatedly condemned for its undemocratic government and vilified whenever it takes any action on the world stage that could be construed as assertive. On social media, it’s filtered through memes about collapsing buildings or doctored videos of empty cities. And in online intellectual circles—especially on the dissident right—there’s a recurring impulse to explain Chinese success or failure in moral terms: if China stumbles, it’s proof that the people are corrupt; if it advances, it must be cheating. The underlying message is consistent: the Chinese cannot be trusted.

A commonly cited piece of evidence for this supposed national character defect comes from an experiment that made headlines in 2019. The study, led by behavioral economist Alain Cohn, was published in Science under the title ‘Civic honesty around the globe’.

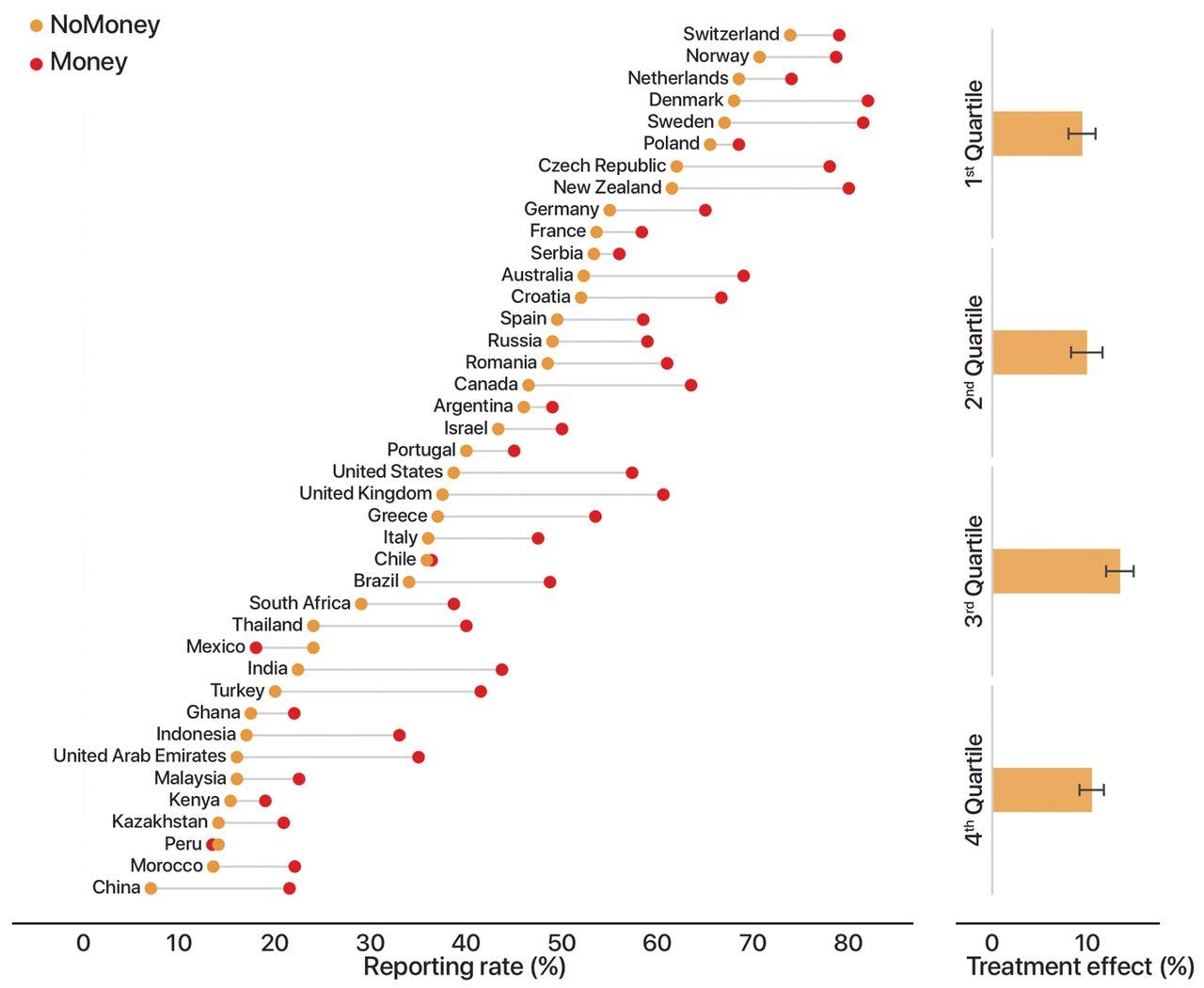

The authors conducted a large experiment in which they dropped over 17,000 wallets in 355 different cities across 40 countries. Some of the wallets contained cash, while others didn’t. Each wallet contained business cards with a name and email address using realistic but fictitious names. Every wallet was assigned its own unique email address. That way, if someone tried to return a wallet, the researchers could identify exactly which one it was (and whether it contained money or not). Emails were tracked for 100 days after the wallets were dropped. In almost every country, wallets with money were more likely to be returned than wallets without money (which runs against the self-interest axiom of modern economics). Even more striking, though, were the vast differences in civic honesty between countries—as shown below.

One country stands out more than any other: China. Despite having a relatively high average IQ (100.2 according to the latest dataset) and a decent standard of living, it performed abysmally. The share of wallets reported as found was among the lowest in the world. To many readers—especially those already inclined to believe in Chinese moral failings—the conclusion seemed obvious: the Chinese are simply dishonest. On the online right, where skepticism of social science is usually high, the study has circulated as confirmation that Chinese civic life is built on deceit. (The Chinese themselves were, understandably, less than pleased about the results.)

However, China’s abysmal performance in this experiment was almost certainly due to methodological bias, rather than any genuine defect of national character.

To begin with, one of the authors of the study, David Tannenbaum, admitted that they had to exclude Japan (one of the dissident right’s favourite countries) because it has very different cultural norms for dealing with lost property:

We originally planned to include Japan but after some initial pilot testing we realized that the country was unsuitable for methodological reasons. Japan has a lot of small “police booths” where people can return lost objects. During our pilot tests, we found that Japanese citizens would not contact the owner but instead drop them off at a nearby police booth. This feature made it virtually impossible for us to assign individual wallets to particular drop-off locations.

So the authors deemed the Japanese to be culturally distinct enough that their methodology might be biased against Japan, but for some reason decided it was okay to include China, a cultural and ethnic cousin. One might speculate as to what the rationale for this was.

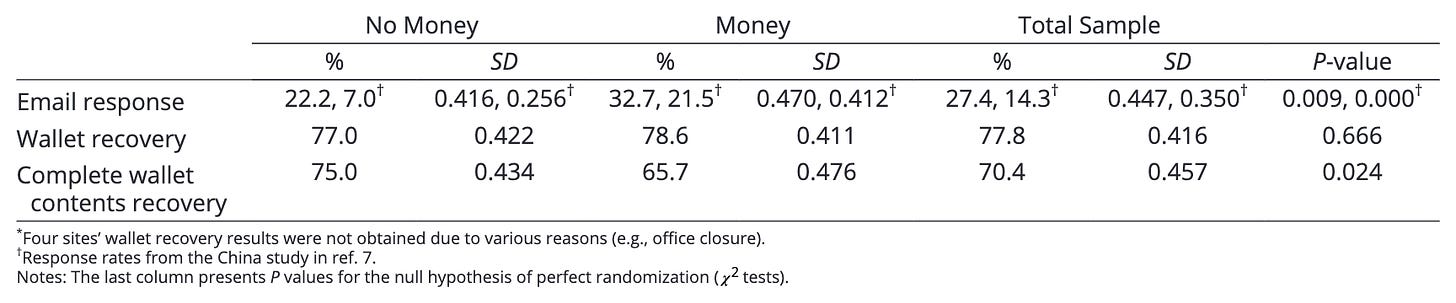

In 2023, a group of Chinese researchers, Qian Yang and colleagues, conducted a replication of the original experiment by dropping 496 wallets (with and without money) across ten Chinese cities. They also added new elements, such as undercover observers (who watched what recipients did after receiving a wallet) and follow-up surveys of recipients. Crucially, they employed three different measures of civic honesty: email response rates (the original method measure), wallet recovery rates (was the wallet actually kept safe and returned?), and complete wallet recovery rates (was everything inside returned too?).

They were able to replicate the low email response rates of the original experiment: 22% for wallets without money and 33% for those with money. However, when it came to wallet recovery rates, they observed much higher values: 77% for those without money and 79% for those with money. (When it came to complete wallet recovery rates, the figures were 75% for those without money and 66% for those with money.) The discrepancy between email response rates and the other two measures arose because many wallets were safeguarded until the owner could come collect them, despite no one emailing.

The authors speculate that civic honesty manifests differently in more collectivistic societies like China. In support of this hypothesis, they found that a significantly greater percentage of respondents in the survey endorsed safekeeping as part of civic honesty, as compared to contacting the owner: 85% vs. 62%. In a back and forth between the original authors and the Chinese researchers, the latter also pointed out that in 81% of cases, multiple employees shared responsibility for the lost wallet, suggesting honesty in China is often collective rather than individual.1

Another potential source of bias in the original study was the contact method used: emailing is not a common way of contacting strangers in China. This can be seen in the results of a recent study by Iris Hung and colleagues. In their field experiment, these authors replaced the email addresses used in the original study with WeChat QR codes. Each wallet carried a unique QR code sticker that, when scanned, opened a WeChat mini-program. From this page, finders could either make a phone call to the wallet owner with one tap, or send a text message through WeChat. Reporting was measured by whether participants scanned the QR code, initiated a phone call, or sent a message through the mini-program. The result? The reporting rate was 59%.2 Taking the results of this study and the one by Yang and colleagues together, it would seem that the civic honesty in China is actually quite high, perhaps even on par with European nations.3

Despite being an ancient civilization, China is not very well understood in the West. Even genuine efforts to research Chinese society often fall short, and this is in large part due to shortcomings with the methods employed. The lost wallet study demonstrates this with regard to civic honesty, but what about self-reported trust? Consider the “generalized trust” item from the World Values Survey. Here are the results by country:

On this measure, China appears to be one of the world’s most trusting societies—well ahead of even most Western nations. The result seems almost too good to be true. Are they?

In 2011, a team of sociologists led by Jan Delhey noticed that the item’s wording might not mean the same thing everywhere. In individualistic cultures, “most people” usually refers to strangers. In collectivist cultures, it tends to refer to one’s ingroup—family members and close friends. Delhey and his colleagues re-analyzed data from the fifth wave of the survey to correct for this difference in meaning.

They utilized the items measuring ingroup and outgroup trust, as well as the generalized trust item. By comparing people’s answers, they were able to estimate out how wide the “trust radius” is in each country. Their results suggest that very low trust is actually the norm throughout the world. In fact, Sweden is the only country on this list to have an adjusted trust score above 50%. After adjusting for the “trust radius” of each country, China’s ranking plunged, though it remained slightly higher than Taiwan and South Korea.

However, the authors caution that China’s adjusted results might still be an overestimate because there were high rates of non-response or “don’t knows” on outgroup trust items. But this raises another question: what kind of distrust are we really measuring here? The “outgroup trust” scale doesn’t just cover strangers you meet on the street. It also includes foreigners and religious outsiders, and China’s non-response was concentrated on the two “xenophobia-sensitive” items. (The authors mention that respondents from China and Ukraine “had particular problems with questions about people of other religions and nationalities”.)

But the problem goes deeper. In their online supplement, Delhey and colleagues explicitly note that the “people you meet for the first time” item—the one meant to capture trust in strangers—did not behave consistently across countries (it was not measurement invariant). As a consequence, they had to relax its factor loading for 18 countries to get an acceptable model fit. Hence in those countries, the outgroup trust factor was driven more by the other two indicators—trust in people of another religion and of another nationality. This tilts the construct away from measuring civic openness to strangers and toward measuring tolerance of outsiders (i.e., xenophobia). Since the authors never reported which countries were affected, we cannot know whether the “people you meet for the first time” item worked properly for China specifically. In a noble effort to correct for one bias in the measurement of generalized trust, the authors wound up introducing a different one.4

In fields like science and technology, China has developed at a remarkable speed. The conventional wisdom is that it simply copies everything from the West, producing nothing novel of its own. Is this true? As Anatoly Karlin argues, one of the best ways to compare countries with respect to innovation is using the Nature Index:

Nobel Prizes in the sciences lag real world accomplishments by 20-30 years. Measures of individual eminence, such as Pantheon, only become crisp in long-term retrospect … Total number of articles published, patents granted, R&D personnel, or R&D spending don’t adjust for quality. University rankings may be biased due to reputational and “brand” name factors …

The Nature Index (natureindex.com) bypasses almost all of these problems. This index measures the amount of publications in the 82 most prestigious scientific journals in the natural sciences. While they account for less than 1% of natural science journals in the Web of Science database, they produce almost 30% of all citations in this sphere.

Something else to note is that since the index is based on prestigious scientific journals, it’s less likely to be gamed by a country simply producing a ton of academic junk (though attempting to game publication-based metrics through paper milling does not seem to work that well in practice). The index has also been validated against other measures of innovation. I was able to update the fractional count of the countries listed on the most recent version, and here are the results.

Back in 2018, China’s per capita rate was 10.9, Taiwan’s was 29.7, and Japan’s was 40.1. Six years later, China is at 35.5, Taiwan is at 35.7, and Japan is at 40.5. In other words, China is now as scientifically productive per capita as Taiwan and has narrowed most of the gap with Japan. In line with this trend, China has entered the top ten of the Global Innovation Index, which comprises 78 indicators. The country’s record suggests that its gains are not merely the product of scale or imitation. In medicine, for instance, China has rapidly increased its share of active drug development, and Chinese drugs are now being licensed by Western pharmaceutical firms—evidence that they meet international standards of quality.

China still lags far behind the West in living standards and, like its Northeast Asian neighbors, faces a severe fertility collapse. It also misallocates much of its human capital, leaving immense potential unrealized. Yet none of this justifies caricaturing China as backward or its people as dishonest.

In public debate, the country is often cast in contradictory terms. On one hand, it is as a menacing juggernaut—a ruthless, calculating power whose state, so capable that it threatens to overwhelm the West. On the other hand, it is dismissed as a “paper dragon”, crippled by incompetence and corruption. These two narratives coexist comfortably because both flatter the same conviction: that China cannot be both competent and legitimate.

The argument that the Chinese are “anti-white” and therefore all this rhetoric against them is justified makes little sense. No non-white nation will ever be “pro-white” by default. The counterexamples some point to—Japan and South Korea—are not exceptions so much as countries shaped by American occupation.5 The Japanese didn’t become a genetically different people after 1945, but you wouldn’t know it from the way rhetoric toward them flipped once they were firmly under U.S. control.

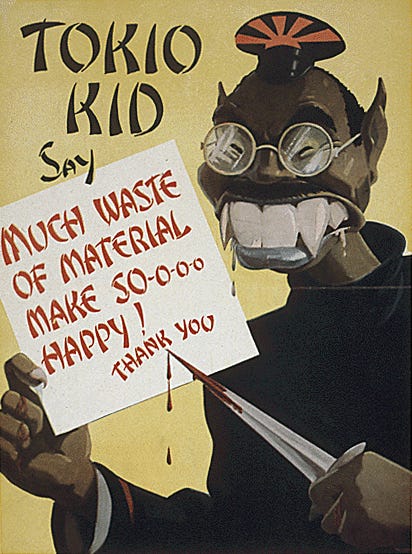

With Imperial Japan crushed and no longer positioned to rival the West, China has inherited the role of primary target for “legitimate” racial resentment. (Russians, after all, are white.) In many people’s minds, the Chinese and Japanese are not kindred peoples with an extensive shared heritage, but practically different species—one sanitized and “acceptable”, the other cast as the eternal bugman.6

The constant insistence that Chinese accomplishments are stolen or illusory functions as psychological reassurance: a way for Westerners to soothe themselves in the face of Western decline. It is easier to dismiss China’s progress than to imagine a world where the West is no longer preeminent. Yet denial does not change reality.

China will not vanish because internet schizos spam “Three Gorges Dam” memes. Nor will the country’s demographic challenges erase its economic gains. By sheer population size alone, it has several decades to adapt before anyone can safely count it out. Dislike of China will not halt mass immigration, restore (non-dysgenic) fertility, or undo the cultural decay hollowing out Western nations. It is easier to laugh at “Chicom bugs” than to confront the failures of our own elites. China’s rise should be a wake-up call: a reminder that nations can still claw their way back from disaster. We can resent that, or we can learn from it. But burying our heads in cope won’t change the balance of power.

A longer version of this article was originally published here.

Alden Whitfeld is an independent writer who does research on immigration and politics. He is co-owner of the blog Heretical Insights and can be found on Twitter.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

A point that Tannenbaum and colleagues made in their letter to the Chinese researchers was that their “total recovery” measure was biased, since wallets without money can’t “lose” money while wallets with money can. Using simulations, they demonstrate that even if there was no true difference between wallets without money and wallets with money, the coding rules employed by Yang and colleagues were basically guaranteed to produce a negative effect. Tannenbaum and colleagues’ own simulations, however, are flawed because their coding assumed independence across wallet conditions, which generated logically impossible scenarios. For example, their simulations sometimes included cases where a no-money wallet “lost money”, or where a whole wallet was missing but some items were intact. A whopping 25.9% of the simulated data points were theoretically impossible. If we accept the validity of Tannenbaum’s criticism though, it would mean that the results for the complete wallet recovery rate for wallets with money in Yang and colleagues’ study is downwardly biased, implying that civic honesty in China is even higher than what they found.

Cohn and colleagues did acknowledge the possibility that email was an uneven measure across cultures. In their supplementary materials, they restricted the analysis to hotels on the grounds that hotel staff should not only be familiar with email, but more likely to use it given their frequent dealings with foreign tourists and businesses. They also adjusted country rankings by national email penetration. Neither check meaningfully changed the results, which led them to conclude that email usage was not a major source of bias. But Hung and colleague’s WeChat-based replication suggests this assumption was overly optimistic. Even in internationally oriented hotels, staff in China evidently did not regularly use email for this kind of interaction, meaning the hotel-only analysis could not actually neutralize cultural bias, which was already made evident in Yang and colleagues’ survey results of the employees themselves, finding that only 39.19% considered not contacting the owner to be civically dishonest whereas it’s 80.91% for retaining the wallet.

Hung and colleagues caution that their reporting rates cannot be directly compared with Cohn and colleagues’ global study because of design differences (e.g., WeChat vs. email, wallet contents, and intervention framing). Unlike the original lost-wallet study, their field experiment only used wallets containing personal items and no money. The direction and magnitude of any resulting bias is unclear. Cohn and colleagues found that even in China, wallets with money were more likely to be reported than those without. Hung and colleagues’ online experiments, which varied wallet contents, likewise showed that money and personal items evoke different psychological responses that shape reporting behaviour.

Because the designs differ on several dimensions, it is not possible to determine whether Hung and colleagues’s design would yield higher or lower reporting than the money-containing wallet conditions in the original study. What can be said with confidence is that the original 7% estimate for China was almost certainly deflated by relying on an unfamiliar communication method. Once this flaw is corrected, measured civic honesty in China rises substantially—even though the true rate cannot be known precisely.

And of course, perception of trustworthiness is different from trustworthy behavior itself. To take just one example: this paper shows South Korea and South Africa end up with comparable adjusted trust scores. But no serious observer would claim that South Korea and South Africa are equally trustworthy societies.

And even then, it’s not clear if those countries today are genuinely “pro-white” in the racial sense beyond being culturally Westernized. Both Japan and Korea had a higher share of respondents answering that they would have voted Democrat (rather than Republican) at the 2024 U.S. presidential election.

I have lived in China since 2010. In the past 15 years, China has transformed from a low-trust society to one of the highest-trust societies, similar to Japan. It is fine to leave your wallet, phone or laptop at a cafe table while you go to the bathroom etc. I leave my $5k bike outside every day with no fear it will be stolen or damaged.

The lost-wallet test doesn’t expose a flaw in Chinese society; it exposes a flaw in the scholars who designed it. They are trying to study a digital civilisation with Stone Age tools. Judging China by a wallet experiment in 2025 is like judging aviation with a pterodactyl. When your methodology belongs to an extinct world, the only dinosaur in the room is the researcher.

👎