Bomb first, ask questions later

How Western foreign policy fuels mass immigration into Europe.

Written by Noah Carl.

Europe has a major interest in stability in the Middle East, “stability” being a euphemism for “countries not descending into chaos”. The reasons are obvious. When countries descend into chaos, millions of people are forced to leave their homes and many of them decide to come to Europe. (Life in a European welfare state looks more attractive than usual when groups of fanatics are blasting at one another in the streets.) But that’s not the only reason. When countries descend into chaos, the government may lose control of key border crossings, allowing people smugglers to operate unimpeded. Or it may cease to exist at all, in which case there’s no longer an entity with whom to strike deals that could stem the flow of migrants.

Despite these fairly obvious points, Western foreign policy often seems to be designed to achieve the exact opposite, namely instability. And regardless of whether it really is designed to achieve this, instability is certainly one of its main consequences. (“Instability” again meaning “countries descending into chaos”.) The issue isn’t so much that the architects of Western foreign policy are trying to cause mass immigration into Europe. It’s that they seem to think mass immigration into Europe is a price worth paying for whatever it is they are trying to do (“punish aggression”, “promote democracy”, “confront Iran” etcetera). Let’s consider the evidence.

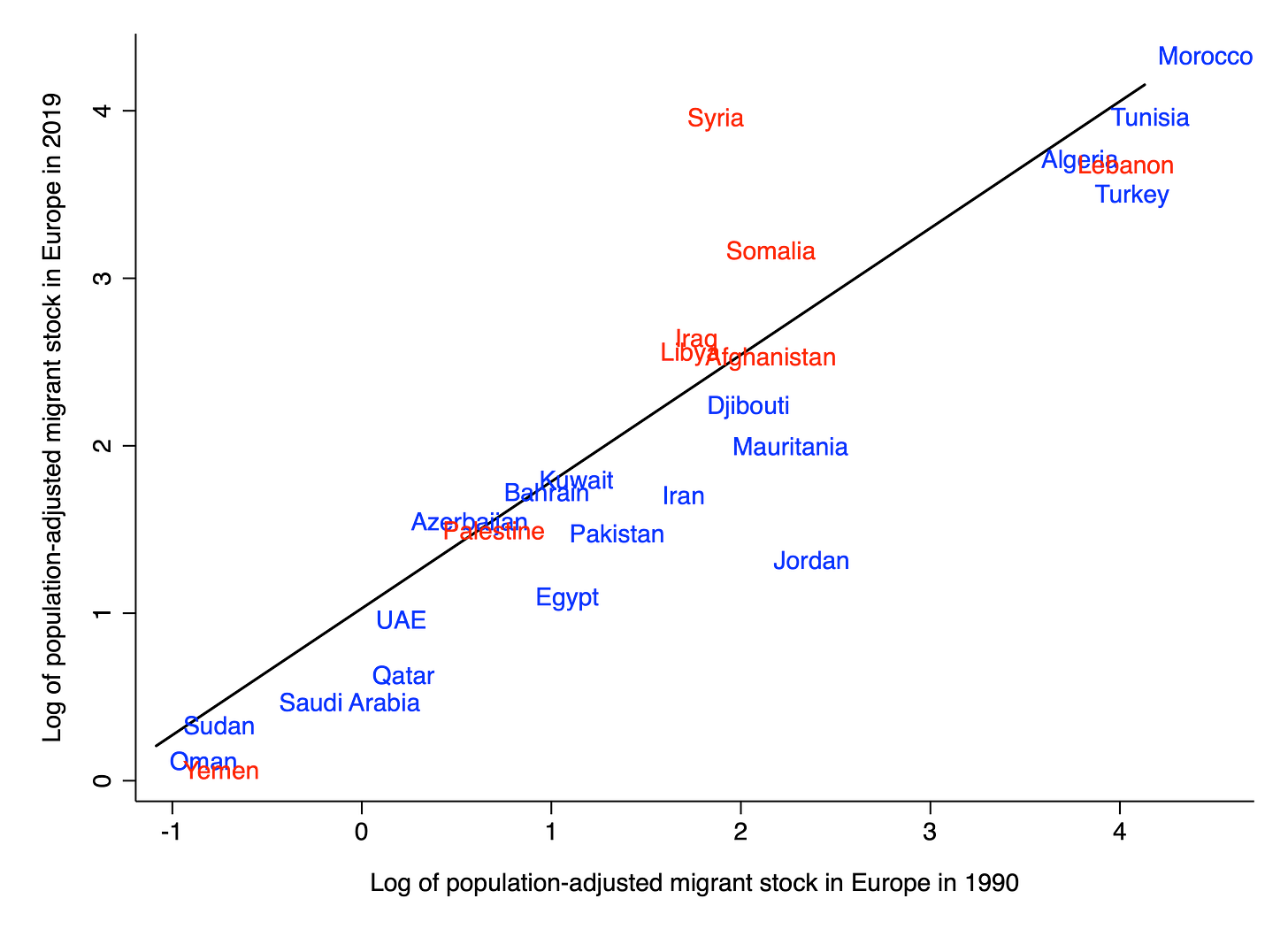

In a recent article for the Daily Sceptic, I examined whether Muslim countries in the Middle East with Western military interventions have seen greater increases in migration to Europe than those without such interventions. To do so, I calculated for each of 26 Muslim countries the population-adjusted migrant stock living in the EU, Britain, Norway or Switzerland in 1990, 2000 and 2019.1 I then looked at the relationship between population-adjusted migrant stock in 1990 and population-adjusted migrant stock in 2019, as well as the relationship between population-adjusted migrant stock in 1990 and population-adjusted migrant stock in 2019. (Two different baseline years were used for the sake of robustness.)

Here are the results using 1990 as the baseline year. Countries that experienced major Western or Western-backed military interventions are shown in red.2

And here are the results using 2000 as the baseline year:

In both comparisons, the countries shown in red are concentrated above the line, while those shown in blue are concentrated below the line. This indicates that countries with military interventions have seen larger increases in population-adjusted migrant stocks than those without interventions. (The two exceptions are Lebanon and Yemen.) When using 1990 as the baseline year, six of the top seven with the largest increases are countries with interventions. And when using 2000 as the baseline year, all five of the top five are countries with interventions.

One important caveat (as noted in the original article) is that in several cases it’s plausible there would still have been large-scale immigration from the relevant country in the absence of Western military intervention. For example, the civil war in Somalia during the 1990s might have produced just as many displaced people if the US had not intervened at all. The method I used may therefore overstate the impact of Western military intervention on mass immigration into Europe.

However, there’s another quite significant way in which it understates the impact of Western military interventions. By comparing changes in migration from Muslim countries with and without interventions, it ignores the impact that interventions in one Muslim country may have had on migration from other Muslim countries and from other parts of the world, notably Sub-Saharan Africa. The clearest example where an intervention in one country directly facilitated migration from other countries is the 2011 NATO intervention in Libya.

In February of that year, a civil war broke out between the government, led by Muammar Gaddafi, and various rebel groups who sought to topple his regime. France, Britain, the US and other NATO countries decided to enter the war on the side of the rebels, and proceeded to carry out more than 7,000 air strikes. Unsurprisingly, this bombing campaign severely degraded the government’s fighting ability, allowing the rebels to gain the upper hand and eventually prevail. In the end Gaddafi himself was killed, allegedly by being sodomised with bayonet. The whole affair was memorably summed up by Hillary Clinton, who stated, while cackling with laughter, “We came, we saw, he died!”

The stated reason for NATO’s intervention was to stop the government attacking and killing civilians in what may have amounted to crimes against humanity. Some such attacks probably did take place, though there were also many false claims circulating at the time. For example, Amnesty International found no evidence that Gaddafi ordered mass rapes or used helicopters against peaceful protestors. The man was clearly a “bad hombre”, but whether Libyans are better off without him is much less clear. Since his regime was toppled, Libya has essentially been a failed state, with rival armed factions jostling for power and Africans being openly sold in slave markets.

Prior to the Western intervention that assisted in ousting and killing him, Gaddafi had been a reliable partner, as diplomats like to say, on the issue of migration. In 2008, he signed the Treaty on Friendship, Partnership and Cooperation with Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, whereby Libya would work to prevent illegal migration and Italy would pay compensation for harms done under colonialism. Or in other words, Libya would get cash in exchange for stopping migrants. By all accounts, the agreement worked remarkably well: in the first year the number of people attempting to cross the Mediterranean fell by 92%.

However, the numbers shot back up during the war that toppled Gaddafi’s regime. According to Frontex (the EU’s coast guard and border agency) there were more than 64,000 illegal crossings on the Central Mediterranean route in 2011, compared to only 4,450 in 2010. The numbers shot up even higher during the Migration Crisis, with more than 620,000 illegal crossings recorded between 2014 and 2017. Libya was at this point embroiled in its second civil war in the span of five years. Had Gaddafi still been in power, it’s plausible that most of the crossings could have been prevented.

In a last-ditch attempt to save his regime, he sent the following message to Western leaders: "Now listen, you people of NATO. You're bombing a wall which stood in the way of African migration to Europe and in the way of Al-Qaeda terrorists. This wall was Libya. You're breaking it." As it turned out, Western leaders were more interested in regime change, even if this had the unfortunate side effect of creating a failed state on Africa’s most popular migrant route. And Gaddafi’s remarks now look rather prophetic. Note that a year earlier he had framed his warning in even starker and less politically correct terms:

Tomorrow Europe might no longer be European, and even black, as there are millions who want to come in. We don't know what will happen. What will be the reaction of the white and Christian Europeans faced with this influx of starving and ignorant Africans? We don't know if Europe will remain an advanced and united continent or if it will be destroyed, as happened with the barbarian invasions.

Indeed, data from Frontex show that a large fraction of the migrants who’ve come to Europe via the Central Mediterranean route are not Libyans at all but people from various countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Eritrea, Nigeria, Gambia, Guinea and Ivory Coast. It’s also worth noting that, rather than comprising helpless women and children fleeing war, the migrants are overwhelmingly men.

All this is a long way of saying that the NATO intervention in Libya not only pushed many Libyans to come to Europe (by air-striking their country back to the roving bandit stage of state formation), but also facilitated the migration of hundreds of thousands of others from across Africa. Gaddafi may not have been smart enough to prevent himself being overthrown, but he certainly understood the dynamics of international migration better than the Western leaders who overthrew him. NATO’s bombing campaign surely ranks as one of the most clumsy and short-sighted policy actions in modern history. “Well, we accelerated mass immigration into Europe, but at least we turned Libya into a train wreck too.”

This is not to say that the correct policy was necessarily to sit back and do nothing (though it may well have been). But there were surely options on the table other than “demolish the regime that has ruled the country for half a century and hope that a pluralist democracy somehow emerges from the rubble”. Even if bombing Libya really was the only way to prevent thousands of civilians from being slaughtered (a highly debatable proposition), simply walking away afterward without ensuring that the country had a stable government was immensely irresponsible.

Shifting to another Middle Eastern country where the West saw fit to intervene, the last week witnessed the stunning collapse of the Assad regime in Syria after 53 years of rule. The civil war that precipitated this collapse has of course already produced millions of refugees – including about one million who reside in Europe.3 If the country now enjoys a period of relative stability, it’s possible that some or even many of these refugees will return home. Though at this early stage, the alternative is perhaps more likely: that the country descends further into chaos, leading to a second mass exodus. Only time will tell which eventuality comes to pass.

When reflecting on the demographic consequences of the West’s often disastrous interventions in the Middle East, it’s worth keeping in mind that most Muslim immigrants living in Europe are from countries where the West has not intervened in recent decades. As of 2019, the three biggest groups are Algerians, Turks and Moroccans. Their entry into Europe had little or nothing to do with Western foreign policy and much more to do with simple chain migration. Nonetheless, it’s entirely appropriate to ask why Western leaders are so keen to meddle in the Middle East when doing so just creates millions more potential migrants.

Noah Carl is Editor at Aporia.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

Specifically, I calculated the number of people from each country living in the EU, Britain, Norway or Switzerland, and then divided that figure by the country’s total population.

The variables were logged to reduce skewness.

You might argue that Western countries should just refuse to take refugees. But the reality is that many will inevitably be taken, especially if the situation from which they are fleeing was partly created by the West.

Noah, thanks for an excellent analysis of Western actions and how they influence immigration into Europe and, I might add, the United States.

"Europe has a major interest in stability in the Middle East, “stability” being a euphemism for “countries not descending into chaos”."

Correction: Europe should have a major interest in stability in the Middle East,..., but it doesn't promote that stability.

"Shifting to another Middle Eastern country where the West saw fit to intervene, the last week witnessed the stunning collapse of the Assad regime in Syria after 53 years of rule. The civil war that precipitated this collapse has of course already produced millions of refugees – including about one million who reside in Europe.3 If the country now enjoys a period of relative stability, it’s possible that some or even many of these refugees will return home. Though at this early stage, the alternative is perhaps more likely: that the country descends further into chaos, leading to a second mass exodus. Only time will tell which eventuality comes to pass."

I believe your second scenario is most likely

The fact is Syria no longer exists; some of it will become Greater Israel, some will become Türkiye, and some perhaps Jordan. The fighting has just begun.

"Despite these fairly obvious points, Western foreign policy often seems to be designed to achieve the exact opposite, namely instability."

Exactly. The theory is that chaos allows for intervention by the West, thereby expanding its influence and control. However, situations of chaos often do not lead to the desired conclusion.

The sheer lunacy of HIlary's destruction of LIbya after the example of the Iraq debacle was the main reason I voted for Trump in 2016. I had no idea of what he would be like in office but I thought it was worth taking a chance that he would not be as bat sh-t crazy as Hilary.