Against Singerism

Peter Singer is rightfully applauded as a philosophical giant. He's also spectacularly wrong.

Written by Bo Winegard.

It is sometimes said that a philosopher’s errors are more illuminating than his truths. If so, Peter Singer deserves his reputation as an intellectual giant—for he is wrong. Spectacularly and extravagantly wrong. But he is wrong with admirable courage and clarity. His influence on modern discourse is deep and deserved. And although he is, as I have said, wrong, he is wrong in the right way. One could certainly say worse things about a philosopher.

Singerism is the philosophy inspired by Peter Singer. Like all isms, it is less sophisticated, less nimble, less subtle than its eponymous inspiration. One can detect its influence inside and outside of academia, from practical applications (e.g., the effective altruism movement) to pop culture (e.g., the television show The Good Place).

I believe that Singerism is not just wrong but pernicious, encouraging an outré morality in which the radicalism of a claim, the extent to which it challenges commons sense, is often treated as a virtue rather than a vice. But I’ll leave that critique aside, for this essay does not aim to catalogue the absurd excesses of Singer’s disciples. It aims instead to demonstrate that Peter Singer is mistaken about the nature of morality and that Singerism, being a simplified and exaggerated extension of his thought, is even more so.

Although it has evolved, Singer’s basic philosophical framework remains largely intact from Practical Ethics. It is marked by three central commitments: (1) utilitarianism; (2) cosmopolitan; and (3) rationalism1. Unfortunately, none of these terms is straightforward. Thus, we must begin with provisional definitions whose full implications will only become clear by the end of this essay.

Utilitarianism. A moral system primarily concerned with the consequences of actions, which often holds that certain mental states, especially pleasure and pain, are the only things of intrinsic value in the universe. As Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer write in their Short Introduction to Utilitarianism:

The fundamental question of ethics is: “What ought I to do?” and the fundamental question of political philosophy is: “What ought we, as a society, to do?” To both questions, utilitarianism gives a straightforward answer: that, to put it simply, the best thing to do is to bring about the best consequences, where “best consequences” means, for all those affected by our choice, the greatest possible net increase in the surplus of happiness over suffering.

Cosmopolitanism. A worldview that rejects the moral claims of localism or particularism and emphasizes ethical obligations to all human beings, regardless of kinship, race, creed, or nationality. In its most radical form, it asks us to view morality from “the point of view of the universe.” As Singer writes in his justly famous essay Famine, Affluence, and Morality:

It makes no moral difference whether the person I can help is a neighbor’s child ten yards from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away…There would seem, therefore, to be no possible justification for discriminating on geographical grounds.

Rationalism. A moral position that holds human reason is capable of discovering moral truths and persuading others of them, and that therefore regards reason as the most important tool in the ethicist’s toolkit. Rationalism need not claim that reason is the chief driver of human behavior, and most rationalists would deny that, but it does insist that reason plays a crucial role in moral understanding. In The Expanding Circle, Singer likens the power of reason in ethics to its role in mathematics, writing:

Beginning to reason is like stepping onto an escalator that leads upward and out of sight. Once we take the first step, the distance to be traveled is independent of our will and we cannot know in advance where we shall end.

I believe all three positions are mistaken, to varying degrees. Since utilitarianism is the most foundational feature of Singer’s moral thought, I address it first, and at greatest length.

To preview my own position: I do not believe morality is entirely relative, nor do I think the attempt to reason about ethics is futile or delusional. But I am deeply skeptical that moral reasoning can uncover unknown or hidden truths about complex ethical dilemmas.

We can affirm with confidence that flourishing communities are good, and that moral frameworks conducive to such flourishing are better than those that are not. This is not a trivial insight. But beyond this modest foundation, our moral thinking quickly flies off into a realm of unhelpful abstractions and bizarre thought experiments. These might be fun to debate, but their relevance to terrestrial morality is dubious.

Utilitarianism and Singerism

In its original, “classical” form, utilitarianism held that the only intrinsic good in the universe was pleasure, and the only intrinsic bad was pain. From this foundation followed a simple imperative: maximize the total amount of pleasure and minimize the total amount of pain. The good will, the noble intention, the cultivated virtue, and the natural right were all subordinate to the sovereign authority of pleasure and pain. What mattered were consequences, not character, not motive, not desert.

An important feature of classical utilitarianism is its commitment to universality and impartiality—what Henry Sidgwick called the axiom of universal benevolence: “each one is morally bound to regard the good of any other individual as much as his own, except in so far as he judges it to be less, when impartially viewed, or less certainly knowable or attainable by him.” A king’s pleasure is not in principle more valuable than a pauper’s; likewise, our own pain is not worse than that of a stranger. Pleasure is pleasure; pain is pain.

Not surprisingly, as philosophers wrestled with the implications of this theory—some defending it and some attacking it—utilitarianism evolved, branching into several distinct forms. The central distinctions, though sometimes blurred, are conceptually straightforward. The first concerns the locus of moral judgment: do we assess the utility of individual acts (act utilitarianism) or of general rules governing action (rule utilitarianism)? The second concerns the kind of utility to be maximized: is it the classical hedonistic notion of pleasure and pain, or something else, such as the satisfaction of preferences?

For most of his career, Singer adhered to a form of act utilitarianism that sought to maximize the satisfaction of preferences. Only in the 2000s did he revise his position, adopting a more sophisticated version of hedonic utilitarianism (see chapter 9 from The Point of View of the Universe). While the distinction between preference and hedonic utilitarianism is not trivial, it is largely irrelevant to most ethical dilemmas and to most of Singer’s controversial and provocative claims. Assertions about the permissibility of some forms of infanticide, or the argument that we owe more to distant strangers than most of us give, were developed well before this shift in his theoretical framework.

In what follows, I will concentrate my critique on hedonic utilitarianism both because it remains the most popular and purest form of the theory, and because Singer now endorses it. However, most, if not all, of the criticisms I will advance apply equally to both hedonic and preference-based utilitarianism.

The most fundamental flaw, the rot at the foundation of utilitarianism, is its core premise that pleasure and pain are intrinsically good and bad, rather than contextually or relationally so. This assumption leads to morally puzzling, even perverse conclusions. For example, on a strict hedonistic view, we should not desire or morally approve of the suffering of depraved rapists, if that suffering has no deterrent or rehabilitative effect2. But common sense suggests otherwise. Inflicting pain on certain individuals can be good precisely because they deserve it. In such cases, pain is not intrinsically bad; and it can even be morally good. Pain, in other words, is only bad in context, when, for instance, it is gratuitously inflicted on the innocent or the vulnerable. Pain is, we might say, intrinsically unpleasant, but not intrinsically bad.

Similarly, on a strict hedonistic view, we should not morally disapprove of pleasure that does not cause harm to others (see John Stuart Mill’s “harm principle”). Yet most people find this implication deeply troubling. Consider, for example, an individual who derives pleasure from watching animated child pornography or from observing children cry on a playground. Even if this behavior results in no additional suffering in the world, many would still judge such pleasures to be morally perverse. That is, most people believe a world with less pleasure of this kind would be better than one with more. Pleasure, then, is not intrinsically good. It can be morally neutral or, in some cases, morally bad.

Worse still for utilitarianism, the claim that pleasure and pain are intrinsically good and bad appears to conflict with other central utilitarian principles, namely, impartiality and universality, when combined with a few premises that are all but indisputable. In fact, the idea that pleasure and pain are intrinsic goods may ultimately prove self-defeating or even vacuous.

Consider the following premises:

Pleasure and pain are intrinsically good and bad. Hence, pleasure should be maximized, and pain minimized.

Human behavior significantly affects the pleasure and pain of others. For instance, being kind to a waiter may bring him joy; being rude may cause anger or distress.

Pleasure and pain play causal roles in motivating behavior. The pleasure of being admired may inspire someone to become a doctor; fear of punishment may deter someone from committing violence.

Some individuals have greater capacity to produce pleasure or reduce pain than others. A charismatic actor beloved by millions may raise global happiness far more than an unknown, unskilled individual ever could.

If we accept these plausible assumptions, the following conclusion is difficult to escape: a consistent utilitarian cannot be impartial about persons, only about utility. Since some individuals generate far more utility than others, their interests must matter more. Thus, the supposed impartiality of utilitarianism collapses into a covert form of moral elitism. Persons are to be valued not as ends, but as instruments of aggregate utility. The famous actor, the brilliant musician, the genius doctor should be treated better than the ordinary farmer or the middling painter.

That result is not only counterintuitive—it borders on incoherent. If we begin with the premise that pleasure and pain are intrinsically valuable, but also accept a few plausible assumptions about human psychology and social life, these states quickly come to function as instrumental goods. They motivate behavior, deter wrongdoing, and serve social purposes. Their moral worth, in practice, is judged by how they contribute to an overall system of utility. At that point, their “intrinsic” value becomes nominal. Seven hedons for Bill the neurosurgeon may be judged more valuable than 50 for Sarah, a homeless addict. Pleasure and pain, within this framework, are not equal in moral standing—they are weighed by what they produce, not by what they are. The very premise that inspired utilitarianism is, in the end, vaporized by its own logic.

Even if this argument is not fatal to utilitarianism, even if a utilitarian can somehow salvage the claim that pleasure and pain are intrinsically valuable, utilitarianism leads to many other perverse conclusions. Consider its implications for criminal justice. On strict act utilitarian grounds, the moral response to a crime should depend not on fairness or desert, but on the net hedonic consequences of various outcomes.

Suppose, for instance, that in a country of 350 million, a famous pop singer is credibly accused of domestic abuse. The act causes -100 hedons of suffering to his spouse. If he is not punished, the emotional harm to her continues, subtracting another -100 hedons. But if the crime becomes public, ten million fans each suffer a minor disappointment, say, -.01 hedons, resulting in a total of more than -1000 hedons, surpassing the victim’s suffering. In this case, the consistent act utilitarian would have to conclude that the crime should be concealed and that punishment, if administered at all, should remain secret.

Most people would find this conclusion morally repugnant. Yet the implications grow worse. If the same crime were committed by an unpopular or unknown man, punishment would be justified, perhaps even required, because fewer people would be pained by the knowledge. In such a framework, justice becomes hostage to celebrity. Moral response depends not on guilt or harm done, but on the size of one’s fanbase.

Of course, a rule utilitarian might respond to this dilemma by invoking a general principle: that the rule “punish people according to transparent, public laws, and make no exceptions” yields better consequences than the rule “calculate utility in each case before administering justice.” Fair enough. But this reply avoids the crucial question. The relevant issue is not which rule generally produces more utility, but whether, in this particular case, it would be morally better, not merely legally convenient, to refrain from punishing the pop singer.

If I understand the rule utilitarian correctly, he must concede that if we could make an exception, then doing so would be the morally superior action. But in that case, the “rule” becomes a tool, not a principle. And if the rule utilitarian refuses to make the exception out of duty to the rule itself, then little remains to distinguish rule utilitarianism from deontology. (See chapter 10 of The Point of View of the Universe for an excellent discussion of rules and esoteric morality.)

Another problem for utilitarianism is that it is unclear what exactly we are supposed to maximize, average utility or aggregate utility. Both, if applied consistently, lead to disturbing conclusions.

Consider average utility first. Suppose we discover another planet inhabited by joyful, sentient beings which is aptly dubbed Utopia. On a scale from 1 to 100, the average utility on Utopia is 98. I don’t know what Earth’s average utility is, but judging from the public record, which is replete with complaints about the misery of existence, it is surely much lower. Let’s say 65.

If the goal is to maximize average utility in the universe, then the morally correct action would appear to be for Utopia to obliterate Earth with a single, devastating nuclear strike because the painless annihilation of Earth immediately raises the universe’s average utility. (For that matter, so would the painless execution of people below the average utility on earth so long as they had no living friends or family members.)

On the other hand, if the goal is to maximize aggregate utility, we encounter a different conundrum famously articulated by Derek Parfit as the Repugnant Conclusion. The basic idea is this: if total utility is what matters, then we can (almost) always imagine a scenario in which average well-being decreases, but total well-being increases, by adding more people whose lives are barely worth living. For instance, if we have 100 people each enjoying a utility level of 90 out of 100, we could improve the overall total by adding 1,000 people whose lives are just above the threshold of despair. The result is a larger population living more joyless lives, but a bigger total utility score. By this logic, a million people in purgatory are morally preferable to a thousand people in paradise.

Furthermore, by this logic, most of us (at least in affluent societies) have a moral obligation to have as many children as possible, so long as those children would live lives above the threshold of suffering. If a couple could achieve a utility level of 70/100 with one child (who also enjoys 70/100), it would be morally preferable, on aggregate utilitarian grounds, for them to endure a lower personal utility (to 55/100) to raise fifteen children who each have lives at that same 55/100 level. Even if this version of the Repugnant Conclusion is more modest than the original, it still contradicts widely held moral intuitions. Strikingly few utilitarians advocate for ultra-fertility. And many, like Singer, defend the moral permissibility of abortion, even though, from the perspective of aggregate utilitarianism, abortion would almost always be wrong, since it prevents the creation of a life that would, presumably, add net utility.

A final problem for utilitarianism is that mental states may be incommensurable and unpredictable, making comparisons across time difficult, perhaps even impossible. Consider what the philosopher L.A. Paul calls transformative experiences—events that radically restructure the psyche, altering a person’s preferences, priorities, and utility landscape. Parenthood is a classic example. Before having a child, someone might be self-focused, devoted to career goals or short-term pleasures. She might imagine parenthood as burdensome, a threat to autonomy, spontaneity, or nightlife. But after giving birth, she might discover that her entire hedonic gestalt has shifted. Dancing, drugs, promotions no longer matter. A laugh or a smile from her child is now the highest good. She is not the same person. And she does not have the same utility function.

How can we determine what would be morally better based on pleasure and pain if we cannot meaningfully compare future mental states to present ones? This is not to claim that such comparisons are always futile or incoherent. Obviously, in most cases, being happily employed is preferable to losing one’s job and living as a vagabond. But in certain important cases, the relevant mental states are so radically different, or so inaccessible from our current perspective, that meaningful comparison becomes virtually impossible.

And if that is so, then we cannot rely solely on personal or even aggregate utility to make moral judgments. We must appeal to something beyond hedonic calculus—something more stable and normative. We would have to invoke a higher good, a deontological good.

Utilitarianism was a laudable attempt to construct a coherent and far-reaching meta-ethical theory. But it has failed. That is not to say it lacks merit. We do, and should, care about the consequences of our actions; and we do, and should, care about pleasure and pain. But we also care about other things, e.g., dignity, justice, rights, character, and desert.

More troubling still, utilitarianism is ultimately self-undermining. Its foundational premises tend to implode under scrutiny, and even when they don’t, they often lead to morally repugnant conclusions. Singer, being a sophisticated thinker, is aware of these difficulties. He occasionally allows space for moral pluralism, especially in difficult cases. But he remains, by his own admission, at least 98% a committed hedonic utilitarian. And many of his more bizarre or unsettling conclusions follow directly from taking that commitment seriously.

Singerism, being simpler and more doctrinaire than Singer himself, is even more vulnerable. It cannot withstand the challenges outlined in this section.

Cosmopolitanism and Singerism

Singer’s most powerful and influential argument, one about a boy drowning in a pond, illustrates his commitment to cosmopolitanism. He begins with a dramatic hypothetical:

On your way to work, you pass a small pond. On hot days, children sometimes play in the pond, which is only about knee-deep. The weather’s cool today, though, and the hour is early, so you are surprised to see a child splashing about in the pond. As you get closer, you see that it is a very young child, just a toddler, who is flailing about, unable to stay upright or walk out of the pond. You look for the parents or babysitter, but there is no one else around. The child is unable to keep his head above the water for more than a few seconds at a time. If you don’t wade in and pull him out, he seems likely to drown. Wading in is easy and safe, but you will ruin the new shoes you bought only a few days ago, and get your suit wet and muddy. By the time you hand the child over to someone responsible for him, and change your clothes, you’ll be late for work. What should you do?

He then observes that virtually everyone would agree you ought to help the drowning child and that failing to do so would be morally reprehensible. From this universal intuition, he arrives at a startling conclusion. Those of us in affluent societies are, in effect, in that very situation every day. For the cost of new clothes or a few fancy meals, we could save a life in a faraway impoverished country. The geographical and emotional distance does not erase the moral obligation; it merely conceals it:

Effective altruists do not discount suffering because it occurs far away or in another country or afflicts people of a different race or religion. They agree that the suffering of animals counts too and generally agree that we should not give less consideration to suffering just because the victim is not a member of our species.

Before assessing Singer’s logic more rigorously, it’s worth noting that with only slight modification, his famous thought experiment can be used to support moral conclusions diametrically opposed to his own.

Imagine this:

You’ve won a unique lottery worth $100,000. There is only one ticket; no records exist elsewhere. If the ticket is damaged, the winnings are lost forever. You keep it safely in your pocket on your way to work.

On the way, you spot a child drowning in a shallow pond. No one else is around to help. You reach to rescue him, but the ticket is stuck in your pocket, and you don’t have time to remove your pants. If you jump in, the ticket will be destroyed. If you don’t, the child will die.

But there’s a catch: you had already planned to donate the entire $100,000 to highly effective charities that would save not just one life, but perhaps twenty.

What should you do?

Is it morally defensible to walk on, thinking, “This is awful. I want to save the child. But it’s more important to save twenty lives in Africa”? My best guess is that virtually nobody would say yes.

In fact, we can squeeze the vice even more tightly.

Suppose the clothes you’re wearing are worth tens of thousand dollars. You were planning to sell them and donate the proceeds to a vetted effective altruist charity, a charity that would, with high probability, save at least two children’s lives.

Now you see a boy drowning in a shallow pond. To save him, you would have to ruin your clothes. Should you walk past, thinking, “Yes, this is terrible. But the greater good requires that I keep walking”?

Of course, neither of these thought experiments shows that Singer is wrong. His thought experiment is, after all, only a thought experiment. It is designed to provoke intuitions, not to make a rigorous philosophical argument. And the fact that can be used to support views quite different from his own does not mean that his views are the wrong ones. But it does mean that the popular thought experiment is flawed.

Here is the more abstract, more rigorous logic of his argument as presented in The Life You Can Save:

First premise: Suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care are bad.

Second premise: If it is in your power to prevent something bad from happening, without sacrificing anything nearly as important, it is wrong not to do so.

Third premise: By donating to aid agencies, you can prevent suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care, without sacrificing anything nearly as important.

Conclusion: Therefore, if you do not donate to aid agencies, you are doing something wrong.

This appears formidable, perhaps irrefutable at first. Yet, upon closer inspection, the second premise is at best debatable. Plausible—but far from indisputable. (The first premise seems nearly incontrovertible, and the third easily defensible, though likely in need of qualification.)

But even granting all three premises, it is far from clear that the death of distant children carries the same moral weight as the loss of personal autonomy or the erosion of one’s ability to participate fully in local moral life, sacrifices that Singerism appears to demand. Indeed, contra Singer, I am prepared to assert that alleged crimes of omission involving distant strangers are not crimes at all. While we undoubtedly have negative duties toward people in faraway places, such as refraining from harming them, we do not have corresponding positive obligations to aid them. The moral distinction between killing and letting die, often dismissed or trivialized by utilitarians, regains its force when moral agency is grounded in proximity, relationship, and community.

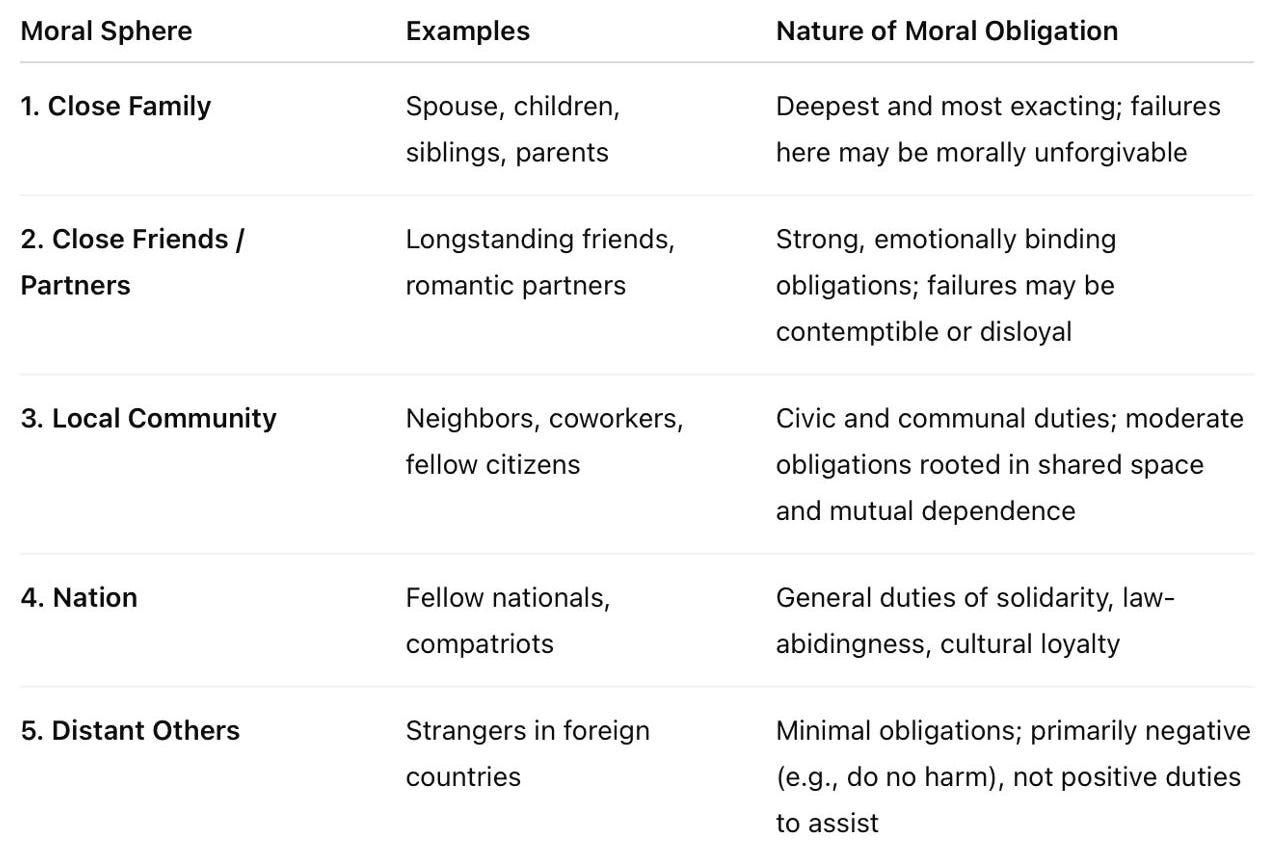

From my anti-cosmopolitan perspective, moral life is structured into concentric spheres3, each with its own expectations and obligations. In the innermost sphere is the family, e.g., husbands and wives, parents and children, brothers and sisters. Here, our moral duties are deepest and most exacting. Neglecting a suffering friend may be contemptible; neglecting a suffering daughter may be unforgivable.

The second sphere includes close personal relationships, e.g., friends, partners, and long-standing companions. Our obligations here remain strong, though not as binding as those within the family. In the third sphere lies the local community, e.g., neighbors, colleagues, fellow citizens. The fourth encompasses the nation. Beyond that, our moral obligations become more faint and more abstract until they become nonexistent.

Consider our intuition about the vast difference in moral obligation we have between family and strangers in distant countries:

Thomas is a successful online chess streamer. He loves his work and earns over $300 an hour, 90% of which he donates to effective charities. Then tragedy strikes. His daughter is diagnosed with cancer. Doctors believe she will survive, but warn of a long and difficult illness. In response, Thomas reduces his streaming hours to five a day and begins keeping all his earnings to pay for her treatments, gifts, and occasional vacations to make her as comfortable as possible during her battle.

This continues for two years. During that time, Thomas forfeits over a million dollars in potential donations and spends another million on his daughter. According to reasonable estimates, that money could have saved the lives of at least 300 strangers through effective altruism.

Yet few of us would say Thomas acted selfishly or immorally. On the contrary, most would regard his choice as deeply noble, an expression of love and duty, not a moral failure.

Even if one is unwilling to adopt my stronger claim that we have no positive duties to strangers in faraway places it remains clear that such duties, if they exist at all, are comparatively weak. Of course, an advocate of Singerism might respond that this is a moral failing, that our intuitions are biased and unreliable, and that we should transcend our parochial sympathies, suppressing our narrow urge to help family more than others. But this strikes me as implausible—indeed as borderline monstrous.

In my view, there is no single meta-ethical theory or universal set of criteria by which all moral decisions can be judged. Instead, different contexts call for different standards. Moral pluralism is not a concession; it is a necessity. And navigating between competing obligations is more an art than a science. Many of our most enduring and agonizing moral dilemmas arise from clashes between distinct spheres of duty. This tension is dramatized in tragedies from Ancient Greece, e.g., Antigone to modern America, e.g., The Godfather. It also surfaces in disturbing thought experiments, such as the choice between saving one’s spouse or three strangers from a burning building.

These dilemmas are agonizing precisely because they defy objective resolution. As Antigone asks: is my duty to bury my brother more important than my obligation to obey the laws of my community? Or, as The Godfather asks: is my loyalty to family more binding than allegiance to my own moral compass? Such conflicts are so deep, so troubling, and so elusive that they may be better explored through literature and art than through a moral philosophy that purports to offer final answers.

Still, while I do not believe these conflicts can be definitively resolved, I do believe we can confidently affirm certain priorities. We should care more about our daughter than a stranger, more about our fellow citizen than a foreigner, more about humans than animals. None of this implies that it is immoral to care for strangers or animals or to dedicate time and resources to their welfare. But it does mean that we are under no moral obligation to intervene in foreign lands to prevent tragedy or to intervene in Canadian forests to protect animals from suffering. And it does mean that moral partialism is not a weakness or bias to be transcended, but a sensible and human way to divide the moral world. Tribe, in this view, is not the enemy of morality, not some primitive proclivity we should suppress, but the very source of morality.

The contention that we owe something significant to distant strangers was provocative and Singer’s thought experiment about a drowning boy in the pond remains captivating. But the claim is implausible, and the thought experiment does not show what it is intended to show. In fact, with a few slight modifications, is shows exactly the opposite. Advocates of Singerism continue to promote bizarre moral claims about our responsibility to distant strangers and future people, but they have yet, in my view, to make a persuasive case for their assertions. And the moral philosophy that supposedly motivates them, utilitarianism, is untenable.

Rationalism and Singerism

To my knowledge, no serious philosopher has ever entirely rejected the power of reason, at least not as a means of persuasion. To do so would be self-undermining and would entail a career-long commitment to a quixotic, and arguably incoherent, endeavor. In this sense, all moral philosophers are rationalists, including David Hume, who famously asserted (in a widely misunderstood passage) that “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.”

When I say that Peter Singer is committed to rationalism, therefore, I mean something more than this. I mean that he believes reason is not merely a tool of persuasion or a servant of sentiment, but a potential source of moral insight, capable of uncovering new and perhaps unsettling ethical truths. And I mean that he is often skeptical of traditional justifications for morality, such as appeals to intuition, emotion, or cultural convention. As Singer writes in the afterward to The Expanding Circle:

Nevertheless, if we can accept the idea of objective normative truths, we do have an alternative to reliance on everyday moral intuitions that, according to the best current scientific understanding, are emotionally based responses that proved adaptive at some time in our evolutionary history. The existence of objective moral truths allows us to hope that we may be able to distinguish these intuitive responses from the reasons for action that all rational sentient beings would have, even rational sentient beings who had evolved in circumstances very different from our own.

To get a sense of how rationalism works in practice, consider a famous moral vignette forwarded in an article by Jonathan Haidt and colleagues:

Julie and Mark, who are brother and sister are traveling together in France. They are both on summer vacation from college. One night they are staying alone in a cabin near the beach. They decide that it would be interesting and fun if they tried making love. At very least it would be a new experience for each of them. Julie was already taking birth control pills, but Mark uses a condom too, just to be safe. They both enjoy it, but they decide not to do it again. They keep that night as a special secret between them, which makes them feel even closer to each other. So what do you think about this? Was it wrong for them to have sex?

The immediate reaction from most people is unequivocal: of course it was wrong. Incest is not only widely reviled but also morally and legally proscribed. But the rationalist, the Socratic gadfly, might press the issue:

Gadfly: But why was it wrong.

Ordinary person: It’s just disgusting.

Gadfly: So is changing a baby’s diaper or cleaning a child’s wound. Is that morally wrong?

Ordinary person: Well no. But incest can cause genetic defects.

Gadfly: Ah, but they used two forms of contraception. There’s no risk of pregnancy.

Ordinary person: It might still harm their relationship.

Gadfly: According to the story, it brought them closer.

Ordinary person: Still—it’s just wrong.

Gadfly: We’ve covered that. I’m asking why it’s wrong.

Ordinary person: It just is!

A rationalist, in my sense of the term, is precisely the kind of philosopher who would conclude that since no good reason has been provided to judge Julie and Mark’s act immoral, then it is not immoral. For the rationalist, moral intuitions and cultural taboos are unreliable biases; reason alone can transcend the prejudices of custom and instinct and reach higher ethical truths. Unsurprisingly, Peter Singer has suggested that there is nothing ethically wrong with Julie and Mark’s encounter despite the wave of intuitive revulsion it provokes.

This is the reason Singer’s thought is challenging. It often defies intuition and contradicts the status quo; therefore, it often demands that we suppress natural reactions and ignore cultural customs. To Singer, the moral truths that intrepid ethicists discover through reason may require radical revisions to our community norms and understandings.

This raises the question: What do we mean when we speak of ethical truths? What could such an ethical truth be that requires radically overturning our notions of morality? Of course, that is an incredibly complicated question about which one could write thousands of pages, so I cannot do it justice in this short essay. However, I will note that I find implausible Singer’s view that moral philosophers can unveil once hidden moral truths just by thinking deeply about the consequences of certain supposedly self-evident moral truths.

Let us suppose, for example, that a moral philosopher begins with a putatively self-evident moral truth and then uses reason to unfurl its implications. In the end, he concludes that killing innocent people is often morally justified. Our response would not be, “Let us carefully assess this reasoning—perhaps he has uncovered a profound new moral insight.” Rather, we would reject both the conclusion and the supposed truth that led to it. We would argue that if a principle leads to the routine killing of innocents, then that principle is not a moral truth, no matter how plausible it first appeared.

Or more relevantly and realistically, if one begins with the claim that only pleasure and pain are intrinsically valuable, and that we must therefore maximize pleasure and minimize pain, but this leads to conclusions such as the moral permissibility of a painless nuclear strike or the preference for a vast, nearly miserable population over a small, happy one, then the initial premise must be called into question. When a moral insight yields repugnant conclusions, we should generally discard the insight, not our repugnance.

Moral reasoning is and should always be constrained by human intuition. A viable moral philosophy cannot overturn everything we already believe about ethics because we would reject such a philosophy with vehemence. A sound moral theory, then, must be humbler, more conservative, and more cautious about forwarding sweeping claims. It should seek not to overthrow long-standing moral convictions but to ease the irritation caused by conflicting intuitions and apparent contradictions.

This is not to say moral objectivity is an illusion. As I noted in the introduction, I believe we can objectively affirm (at least from the standpoint of beings like us) that flourishing communities are good, and that moral principles that promote such flourishing are better than those that do not. At the very least, humans desire to live in flourishing communities. Consequently, norms that foster flourishing are more likely to endure and spread, while those that fail tend to fade. In this limited but meaningful sense, reason has an important role in moral philosophy. It allows us to ask, “What practices or norms might enhance flourishing in this community without violating deeply held moral intuitions?”

However, and this is crucial, we must exercise caution, especially once a society has achieved a reasonable degree of flourishing, as much of the contemporary West has. The justifications for our norms and institutions are often obscure, even to the most perceptive minds. To discard them on the basis of abstract reasoning may be not only intellectually arrogant, but dangerous. “I can’t find a good reason” is not the same as “There is no good reason.” The moral philosopher who discards a revered norm simply because he cannot discern its purpose will more often resemble a naive mechanic who, failing to see the point of the black liquid in his engine, drives off without oil than a bold innovator later celebrated by posterity.

Let us return to the earlier example of Mark and Julie. Moral rationalists such as Peter Singer argue that, in the absence of a good reason, we ought not to condemn such actions. Our intuitions, perhaps especially concerning sexual morality, are frequently unreliable, and in many cases, we are better served by employing reasoned analysis. As Joshua Greene suggests, this means shifting from the intuitive, “automatic” mode of moral judgment to a more reflective, “manual” mode.

My conservative position, on the other hand, is much more cautious. Maybe ordinary people cannot articulate a precise, philosophically coherent reason for objecting to the highly artificial incest in Haidt’s vignette, but that certainly does not mean there are no reasons for objecting.

Perhaps, for example, a community that strongly discourages incest but allows for rare, nuanced exceptions would be less functional than one that permits no exceptions at all. Or perhaps the claim that Mark and Julie’s relationship was unharmed is implausible or at least unknowable in advance. Consider the following scenario:

Thomas loves driving but has never driven drunk. On his 30th birthday, he decides to try it, just once. Being cautious by nature, he plans to get drunk at night and drive only through his small town when the roads are empty. After consuming ten beers, he drives for an hour, performs doughnuts in the street, and is even cheered by a few onlookers. No one is hurt. He enjoys the experience but resolves never to do it again. Was his action morally wrong?

My guess is that most people would say that it was wrong even though no obvious harm occurred. The key moral question is not what were the consequences? but what could the consequences have been? Even a utilitarian should acknowledge the moral weight of foreseeable risk, even if he does not admit the validity of other moral concerns related to duties and responsibilities.

At any rate, even if my speculations about Mark and Julie are mistaken, the important point remains: the norms and institutions handed down by tens, hundreds, even thousands of generations may be wiser than the wisest individual philosopher. Yes, norms and ethical beliefs are fallible; but more fallible still is the judgment of any single person, however clever, insightful, or thoughtful he is. Of course, this does not mean we should blindly defer to every cultural norm or widely held belief. Critical reflection is a crucial part of the West’s success. But it does mean we should be cautious about assailing long-standing norms. Novel moral ideas, perhaps especially those that provoke strong intuitive resistance, should be presumed false until they have been thoroughly tested.

Ordinary moral intuitions strongly support deontological notions that some acts are almost always wrong regardless of their consequences (e.g., incest). They also support some version of a hierarchy of duties and responsibilities. Close family members are morally more important than strangers. Fellow citizens are more important than foreigners. The rationalist who contends that these intuitions are erroneous or lamentable had better forward very strong arguments against them, perhaps including examples of societies that flourish without them. Because ultimately a moral principle is only as good as the community of real humans it can foster. And the effects of radically restructuring our moral views are incredibly difficult to predict a priori. What leads to flourishing in the mind (e.g., communism) may lead to despair on earth.

One reason for the appeal of Singerism, especially among young college students, is the frisson of excitement generated by its bold and counterintuitive moral claims. It is to ethics what The Doors were to rock. Baffling to parents, hated by conservatives, yet irresistibly seductive to the thoughtful and rebellious. It just sounds so reasonable if you think about it hard enough! Nietzsche might see in this the veiled assertion of power, a way of using dialectical prowess to dominate others. Perhaps that’s uncharitable. And in any case, motives are not particularly relevant here. What matters is that counterintuitive but seemingly rational positions tend to appeal to the young and the intellectually ambitious. And that makes moral philosophy particularly vulnerable to the excesses of rationalism.

In my view, the thankless task of the responsible ethical philosopher is not to upend, but to restrain: to combat excesses of moral overreach and, perhaps above all, to defend common sense, especially in societies that are already flourishing. It is worth remembering that there are far more ways to be wrong than to be right. And flourishing communities are, by definition, already getting the fundamentals right.

Singer and Singerism

Peter Singer is a towering philosopher whose influence is vast. He has challenged many traditional beliefs and dogmas—always through lucid argument, and (almost) never through mockery or belittlement. For this reason, his works are a pleasure to read. He is everything a philosopher should be: thoughtful, honest, clear, eager to dispute rather than to silence. Against cruelty. Against censorship. Against anti-intellectualism and obscurantism.

But he is wrong. Wrong about utilitarianism, wrong about our obligations to strangers, wrong about reason, and wrong about the nature of moral truth. And yet, he remains one of the greatest living philosophers. For that is the nature of philosophy: often, the debate is more vital than the conclusion.

Singerism, by contrast, is wrong in the way crude Marxism or Freudianism is wrong, without the brilliance of its originator. It deserves scorn more than admiration. Yet in the spirit of Singer himself, we should not merely dismiss it. We should argue against it.

Bo Winegard is an Editor of Aporia.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

Importantly, I do not mean rationalist in the sense of the school of so-called rationalists in (largely in epistemology) from Descartes through Leibniz and Spinoza.

One might argue that a strict hedonic utilitarian could approve of pain without deterrent or rehabilitative effect if that pain increased the overall pleasure of society, e.g., if enough people felt schadenfreude to make up for the pain.

Singer accepts that humans do have concentric spheres of moral concern and even concedes that some of this is good since loving parents are better than strangers. So the debate here is normative not descriptive. I think we have little to no positive obligations to strangers in other countries. Singer disagrees.

I think some of the main failure points of utilitarianism come from the short-sightedness of its followers, such as their ignorance of long-term consequences and even competing ethical frameworks like kin selection (and how they came about).

If you observe utilitarians, they take the future for granted and devote their resources to things like open borders, foreign aid, climate change, and even things beyond their own species like bug suffering. The counterevidence and counterfactuals are not explored much nor carried far into the future (like Aporia's articles do in criticizing open borders). They think in a short-termist way which doesn't take multigenerational and unintended effects into account.

Most of them effectively neuter themselves in the process, too; i doubt their fertility is anywhere near replacement-level. So, they devote resources into a future that is clearly unsustainable even in maintaining their own goals.

Even as someone who has some utilitarian elements to my morality (I'm a vegan who has non-zero care about bug suffering!), I left "full" utilitarianism because of these clear failures. Kin selection should always be the primary focus of moral systems. Other considerations can come second. Imo, put your own mask on before helping others (even if you're a utilitarian, lol).

This reminds me of a recent discovery about the book of Ecclesiastes in the Bible. As I was reading it, I realized that Solomon's discoveries were completely independent of Adam and Eve, the Original Sin, and our fallen nature. Somehow, those important stories from the book of Genesis were not anywhere in Solomon's consciousness. He was spinning his wheels. The whole book is just puffs of air and vanity, alright.

You can probably guess why this came to mind. Singer's perfect world is also completely void of our fallen nature. There are a zillion ways to characterize what is wrong with society. But you can't talk seriously about how to improve it without acknowledging this.

Singer is looking at the gameboard without understanding the rules. I am imagine that he and I could put together an experiment to test my hypothesis, although I have a day job that this does not fall within.