Written by Alden Whitfeld.

Epigenetics began as a legitimate branch of molecular biology: a way to explain how the same genome can produce wildly different cell types, how a liver cell knows it’s a liver cell and a nerve cell knows it’s a nerve cell. The term itself refers to chemical or structural modifications to DNA or its associated proteins that determine whether a gene is “on” or “off” without changing the underlying sequence. The classic example is methylation — the addition of a methyl group to a stretch of DNA.

In principle, it offers a powerful insight: genes are not destiny. The “genetic blueprint” can be annotated, regulated, muted or amplified according to developmental cues, changes in diet and stress, and more. This gives organisms much greater biological plasticity than allowed by the genetic code alone.

Because of this insight, epigenetics has attracted considerable attention outside the field of molecular biology (Juengst, 2014). It seems to offer an alternative to strict “genetic determinism”, a way to explain why children don’t always resemble their parents, why adversity might “leave a biological mark”, and why our fate isn’t written in our DNA.

Indeed, it has spawned a popular and social-scientific narrative according to which stress in one generation subtly influences how genes are expressed in the next. Epigenetics became the scientific-sounding justification for “inherited trauma”, “ancestral stress”, and other emotionally resonant ideas. A likely reason this narrative emerged is that it dovetails with moral and political claims about the lingering impact of slavery, colonialism and racism.

The reality is that epigenetic effects in humans, while real, have been greatly overhyped.

There isn’t even a stable biological mechanism capable of transmitting environmentally induced epigenetic changes across multiple generations. This is due to a basic fact about our reproductive biology: mammalian germ cells undergo two rounds of epigenetic reprogramming, one during gamete formation and another immediately after fertilization, which wipe the slate nearly clean. Any methylation mark or chromatin modification acquired from stress, diet or environment is overwhelmingly likely to be erased long before it ever reaches a grandchild (Bird, 2024; Heard & Martienssen, 2014; Horsthemke, 2018; Reik et al., 2001; Zeng & Chen, 2019).

A common fallback claim is that even if germline transmission doesn’t work, the womb might still carry the mother’s life history forward through subtle epigenetic programming. Since the uterine environment is shaped by the mother’s body and life history, maybe an “epigenetic echo” still passes to offspring indirectly through the womb. But if that were true in any robust sense, monozygotic twins who share the chorion—and are thus the closest we get to a “natural experiment” on uterine environmental effects—should differ in their similarity compared to monozygotic twins who don’t. But in fact, there is no difference (Kirkegaard, 2016).

In other words, if someone wants to argue that trauma can “echo through the germ line”, the burden is on them to explain how these marks survive the biochemical equivalent of a hard-drive reformat performed twice per generation. As Razib Khan notes:

For humans and all complex organisms, epigenetics remains both incredibly important and ubiquitous, but solely as a cellular and developmental phenomenon. To understand epigenetics in its full power, you talk to a molecular biologist that works with DNA, not a therapist probing the pain points of your family history (Khan, 2022).

This brings us to rodent studies, the supposed “proof of concept” for how epigenetic inheritance might work. These studies are cited endlessly in popular writing, often without any explanation of what they actually show. The famous example is that stressed mother rats tend to produce stressed offspring. But this phenomenon is already fully explained by behavior: stressed dams provide less maternal care, which itself is stressful and alters glucocorticoid signaling in their pups. That is not epigenetic inheritance through the germ line. It’s bad parenting.

For such inheritance to be genuine, the mechanism would need to look very different. A stress-induced epigenetic change in the brain of an adult animal would have to appear simultaneously in the germ cells, survive the genome-wide erasure in the zygote, remain intact during the next generation’s embryonic development, and then be reproduced in the very same brain regions.

The most influential rodent papers allegedly demonstrate this. Consider the widely cited study by Franklin et al. (2010) titled ‘Epigenetic Transmission of the Impact of Early Stress Across Generations’. It leaves the impression that early-life maltreatment in mice is passed down through the male germ line to children and grandchildren.

Yet as Kevin Mitchell has pointed out, when you dig into the findings, they have all the hallmarks of researcher degrees of freedom: multiple tests, no preregistration, post-hoc slicing, uncorrected multiple comparisons and inconsistent directions of effect — a pattern that would not survive even the mildest statistical discipline. For example, first-generation females show an effect on one test. Second-generation males show an effect on a different test. And other tests show nothing. This is not a coherent biological signal, it is statistical noise being interpreted as “inheritance”.

Meanwhile, in the “cocaine resistance” study by Vassoler et al. (2012), the predicted direction of the effect was reversed, appeared only in one sex, and seemed equally compatible with a dozen different stories. Hypotheses change after the fact, significance thresholds drift, and unexpected results are reframed as “intriguing”. And consider the following from Mitchell:

These studies also suffer from an additional possible confound – the possibility that interacting with a stressed or strung-out male animal will alter the behaviour of the female, post-mating, so that maternal care is also changed. This would be quite different from the model that some experience causes an epigenetic mark in the male germ cells that, in effect, transmits a “memory” of that experience to the next generation. The best way to test for such an effect is to see if it is really transmitted through the male gametes themselves using in vitro fertilization. One study that did just that found effectively no such transmission (Mitchell, 2013).

The rodent studies highlight a larger problem with the entire genre of “epigenetic trauma” research, which is that no one ever stops to ask what solid evidence would even look like.

If the claim is that environmental shocks leave durable biochemical marks on the DNA, and those marks survive the developmental demolition derby of early embryogenesis, and then survive again into the next generation’s germ cells, and then change phenotype in a measurable, replicable way, all those steps need to be demonstrated. What we have instead are a handful of noisy observational studies that would fail to impress even if the question were trivial, let alone one of the boldest claims in biology — namely, a partial rewriting of inheritance.

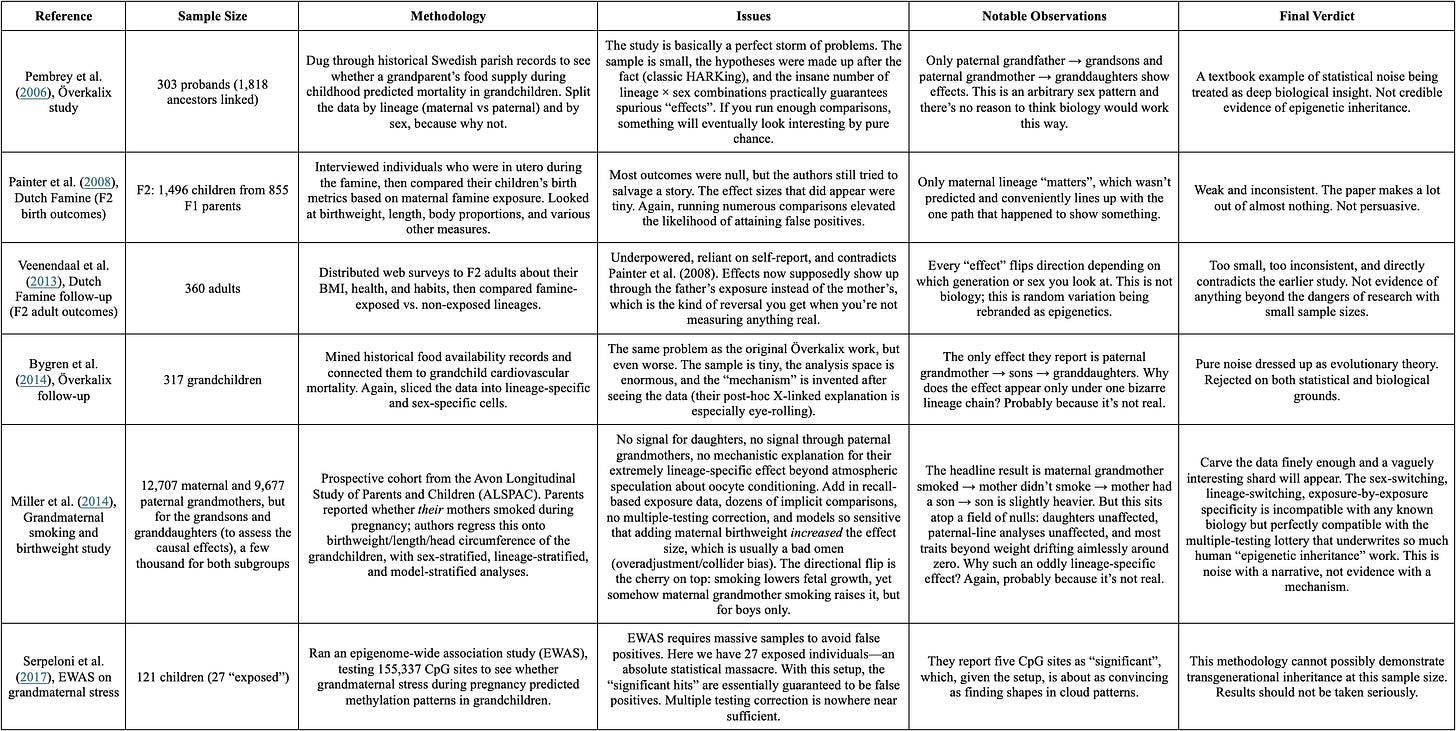

If epigenetic inheritance did exist in humans, you would expect to see it in large datasets with clear temporal ordering. Instead, what gets cited are studies so unreliable a coin flip generates more stable patterns. To make this concrete, below are a handful of studies that continue to be recycled in pop-science discussions of “inherited trauma”. (They were initially compiled by Mitchell, 2018). They supposedly demonstrate transgenerational epigenetic effects in humans. Yet once they are placed side by side, the pattern that emerges is not mysterious or profound; it’s statistical noise being reinterpreted as biology.1

All of this would be enough to show that transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans is a fringe possibility at best. But the empirical record is even less kind than the story so far suggests.

When it comes to the famous Dutch Hunger Winter studies, which are often held up as proof of “epigenetics”, the observed associations between adverse prenatal environments and long-term changes in DNA methylation may simply be caused by selective survival of embryos. This possibility was shown by Tobi et al. (2018) who analyzed data from the relevant cohort and found that selection can produce changes in DNA methylation in survivors that mimic those attributed to epigenetic inheritance.

Another common line of evidence for transgenerational epigenetic effects comes from Holocaust survivors. But a recent review of the literature by Charney et al. (2025) uncovered more methodological flaws and inconsistent results.2 As a matter of fact, the review even found suggestive evidence that prenatal trauma had positive effects on the mental health outcomes of offspring of Holocaust survivors. This is not remotely plausible, and with the results being all over the place, the most likely explanation is that no real effect exists.

Banos et al. (2018) carried out a detailed analysis of CpG sites in over 5,000 Scottish adults, using a model that adjusted for many factors. On the surface, the results look dramatic: methylation patterns collectively explained two-thirds of the variance in BMI and lifetime smoking, even after subtracting everything already explained by SNPs.

This seems like a triumph for environmental programming. But the authors actually did the crucial follow-up work: simulations and pathway analyses. Both pointed clearly to reverse causation. Obesity and chronic smoking induce widespread physiological changes, which in turn alter methylation at thousands of sites. The methylation marks are real, but they are downstream biomarkers of the phenotype, not upstream causal drivers, and certainly not heritable molecular memories.

Additional evidence of reverse causation comes from Li et al. (2018), which examined smoking behavior using a twin study. If methylation truly caused smoking, then a twin’s methylation levels should predict her co-twin’s smoking behavior even after adjusting for her own. Instead, the effect only ran the other way: a woman’s own smoking status robustly predicted her co-twin’s methylation level. The purported effect evaporated under within-pair adjustment.

In the classical twin design, the variance components are A, C, and E. The latter, dubbed “non-shared environment”, is widely interpreted as “idiosyncratic life experiences”. Yet as Kan et al. (2010) demonstrated, the phenotypic variation produced by epigenetic processes is completely absorbed into the non-shared environment (E) term.3 Molenaar et al. (1993) had previously uncovered the same phenomenon using animal data: inbred, environmentally standardized mice and flies still vary in terms of body weight and bristle number — because of intrinsic developmental instability. Due to its unsystematic nature, this instability cannot serve as a stable and persistent mechanism to transmit a phenotype, let alone across multiple generations.

Behavioral epigenetics is even shakier. In a response to Burt & Simons’ (2014) critique of twin-based heritability estimates in criminology, Moffitt & Beckley (2015) reviewed the criminology literature and concluded that nearly every putative link between social adversity and methylation is confounded by genes.

Most differentially methylated sites are themselves under genetic regulation; blood-based methylation patterns correlate poorly with the brain regions that actually regulate behavior; and effect sizes are minuscule. Studies are also confounded by age, sex, cell composition (varying white blood cell counts skew methylation reads), smoking, and medication, making it extremely difficult to draw causal inferences. Their conclusion is blunt: twin and adoption studies remain vastly superior tools for understanding environmental influence on behavior.

All of this reinforces the finding of George Davey Smith’s review of a hundred years of research into epigenetic inheritance, namely that it contributes little or nothing to phenotypic resemblance across generations (Davey Smith, 2012). The key evidence is as follows:

Twin studies, adoption studies, and extended pedigree designs consistently find substantial genetic contributions to phenotypic resemblance, and typically yield similar estimates. If environment-only models were viable, these different designs would not converge so tightly.

Heritability estimates for animals raised in controlled labs or captivity are similar to those for animals raised in messy, natural wild environments. If environmental stressors were transmitted across generations, wild populations should show much lower heritability estimates than laboratory ones. They don’t.

Historical “pure line” experiments, such as Johannsen’s work with beans and extensions to other organisms via inbreeding, self-pollination, parthenogenesis, and cloning, demonstrate that phenotypic variations within genetically identical lines are not transmitted to offspring; selected extremes regress fully to the mean, indicating epigenetic differences do not produce stable inheritance.

A large body of evidence from studies across plants and animals shows consistent negative results for the intergenerational transmission of environmentally induced traits, leading geneticists to dismiss epigenetic inheritance as quantitatively minor compared to genetics.

While research in some plants and worms show isolated cases of epigenetic effects being inherited (e.g., longevity in C. elegans, leaf hairiness in monkey-flowers, methylation in dandelions), these are organism-specific, often lack phenotypic effects (i.e., observable or measurable alterations in the organism’s characteristics), and are minor or dissipate quickly.

As the review noted: “The conclusion from over 100 years of research must be that epigenetic inheritance is not a major contributor to phenotypic resemblance across generations, yet strangely—and perhaps because of the unexceptional nature of the findings—this vast literature has, in some circles, been forgotten. Instead, occasional examples of phenotypically consistent epigenetic inheritance relating to a particular phenotype in a particular organism are given considerable attention, with the implication that they represent a general phenomenon” (Davey Smith, 2012, p. 241).

Taking all the evidence together, it is clear that epigenetics is not a major source of phenotypic variation within humans. As Steven Pinker writes in the afterword to his book The Blank Slate (2002/2016):

Inflating the epigenetics bubble is a set of findings that genuinely are surprising, namely that some epigenetic markers attached to the DNA strand as a result of environmental signals (generally stressors such as starvation or maternal neglect) can be passed from mother to offspring. These intergenerational effects on gene expression are sometimes misunderstood as Lamarckian, but they’re not, because they don’t change the DNA sequence, are reversed after one or two generations, are themselves under the control of the genes, and probably represent a Darwinian adaptation by which organisms prepare their offspring for stressful conditions that persist on the order of a generation … Moreover, most of the transgenerational epigenetic effects have been demonstrated in rodents, who reproduce every few months; the extrapolations to long-lived humans are in most instances conjectural or based on unreliably small samples. Biologists are starting to express their exasperation with the use of epigenetics as “the currently fashionable response to any question to which you do not know the answer,” as the epidemiologist George Davey Smith (2011) has put it.

The popular idea of epigenetics as a kind of molecular séance where the ghosts of your ancestors whisper their traumas into your germ line isn’t just unsupported; it’s reverse-engineered wishful thinking — all for the purpose of satisfying leftist cultural appetites. None of this diminishes the field of epigenetics (the version molecular biologists actually work with), which is intricate and essential. But epigenetics is not — and has never been — a mechanism for replaying the psychological VHS tapes of your great-grandparents’ hardships.

But because the concept itself offers just enough conceptual wiggle room, it has become the vehicle for a sort of Neo-Lamarckian revival. The gap between the science and the story is now so wide that it’s almost comical. And it’s very hard to avoid the observation that a lot of the enthusiasm survives precisely because the evidence is so thin. When a claim is too vague to disconfirm, it becomes infinitely reusable.

Epigenetics has been drafted into service as an explanatory wildcard — something you can invoke whenever you want a biological story but don’t want the constraints of actual biology.4 And when you test the grand claims in real data, they simply fail to materialize.

Alden Whitfeld is an independent writer who does research on immigration and politics. He is co-owner of the blog Heretical Insights and can be found on Twitter.

Become a free or paid subscriber:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

References

Banos, D. T., McCartney, D. L., Battram, T., Hemani, G., Walker, R. M., Morris, S. W., Zhang, Q., Porteous, D. J., McRae, A. F., Wray, N. R., Visscher, P. M., Haley, C. S., Evans, K. L., Deary, I. J., McIntosh, A. M., Marioni, R. E., & Robinson, M. R. (2018). Bayesian reassessment of the epigenetic architecture of complex traits. bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory).

Bird, A. (2024). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: a critical perspective. Frontiers in Epigenetics and Epigenomics, 2.

Burt, C. H., & Simons, R. L. (2014). Pulling back the curtain on heritability studies: Biosocial criminology in the postgenomic era. Criminology, 52(2), 223–262.

Bygren, L., Tinghög, P., Carstensen, J., Edvinsson, S., Kaati, G., Pembrey, M. E., & Sjöström, M. (2014). Change in paternal grandmothers´ early food supply influenced cardiovascular mortality of the female grandchildren. BMC Genetics, 15(1), 12.

Charney, E., Darity, W., Jr, & Hubbard, L. (2025). How epigenetic inheritance fails to explain the Black-White health gap. Social science & medicine (1982), 366, 117697.

Davey Smith, G. (2012). Epigenesis for epidemiologists: does evo-devo have implications for population health research and practice? International Journal of Epidemiology, 41(1), 236–247.

Franklin, T. B., Russig, H., Weiss, I. C., Gräff, J., Linder, N., Michalon, A., Vizi, S., & Mansuy, I. M. (2010). Epigenetic transmission of the impact of early stress across generations. Biological Psychiatry, 68(5), 408–415.

Heard, E., & Martienssen, R. A. (2014). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: myths and mechanisms. Cell, 157(1), 95–109.

Horsthemke, B. (2018). A critical view on transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans. Nature Communications, 9(1), 2973.

Juengst, E. T., Fishman, J. R., McGowan, M. L., & Settersten, R. A., Jr (2014). Serving epigenetics before its time. Trends in genetics : TIG, 30(10), 427–429.

Kan, K., Ploeger, A., Raijmakers, M. E. J., Dolan, C. V., & Van Der Maas, H. L. J. (2010). Nonlinear epigenetic variance: review and simulations. Developmental Science, 13(1), 11–27.

Khan, R. (2022, December 19). You can’t take it with you: straight talk about epigenetics and intergenerational trauma. Razib Khan’s Unsupervised Learning. Accessed at: https://www.razibkhan.com/p/you-cant-take-it-with-you-straight

Kirkegaard, E. O. W. (2016, March 19). Is sharing the chorion important? (No). Clear Language, Clear Mind. Accessed at: https://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/2016/03/is-sharing-the-chorion-important-no/

Li, S., Wong, E. M., Bui, M., Nguyen, T. L., Joo, J. E., Stone, J., Dite, G. S., Giles, G. G., Saffery, R., Southey, M. C., & Hopper, J. L. (2018). Causal effect of smoking on DNA methylation in peripheral blood: a twin and family study. Clinical Epigenetics, 10(1), 18.

Miller, L. L., Pembrey, M., Smith, G. D., Northstone, K., & Golding, J. (2014). Is the growth of the fetus of a non-smoking mother Influenced by the smoking of either grandmother while pregnant? PLoS ONE, 9(2), e86781.

Mitchell, K. (2013, January 14). The Trouble with Epigenetics (Part 2). Wiring the Brain. Accessed at: http://www.wiringthebrain.com/2013/01/the-trouble-with-epigenetics-part-2.html

Mitchell, K. (2018, May 29). Grandma’s trauma – a critical appraisal of the evidence for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans. Wiring the Brain. Accessed at: http://www.wiringthebrain.com/2018/05/grandmas-trauma-critical-appraisal-of.html

Moffitt, T. E., & Beckley, A. (2015). Abandon twin research? Embrace epigenetic research? Premature advice for criminologists. Criminology, 53(1), 121–126.

Molenaar, P. C. M., Boomsma, D. I., & Dolan, C. V. (1993). A third source of developmental differences. Behavior Genetics, 23(6), 519–524.

Painter, R., Osmond, C., Gluckman, P., Hanson, M., Phillips, D., & Roseboom, T. (2008). Transgenerational effects of prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine on neonatal adiposity and health in later life. BJOG an International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 115(10), 1243–1249.

Pembrey, M. E., Bygren, L. O., Kaati, G., Edvinsson, S., Northstone, K., Sjöström, M., & Golding, J. (2006). Sex-specific, male-line transgenerational responses in humans. European Journal of Human Genetics, 14(2), 159–166.

Pinker, S. (2002/2016). The blank slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Penguin.

Reik, W., Dean, W., & Walter, J. (2001). Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Science, 293(5532), 1089–1093.

Serpeloni, F., Radtke, K., De Assis, S. G., Henning, F., Nätt, D., & Elbert, T. (2017). Grandmaternal stress during pregnancy and DNA methylation of the third generation: an epigenome-wide association study. Translational Psychiatry, 7(8), e1202.

Tobi, E. W., Van Den Heuvel, J., Zwaan, B. J., Lumey, L., Heijmans, B. T., & Uller, T. (2018). Selective survival of embryos can explain DNA methylation signatures of adverse prenatal environments. Cell Reports, 25(10), 2660-2667.e4.

Vassoler, F. M., White, S. L., Schmidt, H. D., Sadri-Vakili, G., & Pierce, R. C. (2012). Epigenetic inheritance of a cocaine-resistance phenotype. Nature Neuroscience, 16(1), 42–47.

Veenendaal, M., Painter, R., De Rooij, S., Bossuyt, P., Van Der Post, J., Gluckman, P., Hanson, M., & Roseboom, T. (2013). Transgenerational effects of prenatal exposure to the 1944–45 Dutch famine. BJOG an International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 120(5), 548–554.

Zeng, Y., & Chen, T. (2019). DNA methylation reprogramming during mammalian development. Genes, 10(4), 257.

Amusingly, the authors of this review are political leftists motivated to refute the narrative of “transgenerational slavery trauma”, in large part, because they believe it shifts attention away from supposed ongoing systemic racism against American blacks. For explaining the black-white health gap, they claim “there is no justification needed beyond the key role of structural racism experienced directly by African Americans today” (Charney et al., 2025, p. 2).

This refers to any developmental process layered on top of the genes that amplify tiny initial fluctuations into phenotypic differences.

From personal observation, the people who believe in large, widespread transgenerational epigenetic effects are the ones who seem deeply motivated to invalidate hereditarianism. They need a sense of assurance that it’s anything but the genes themselves. As just one example of how ridiculous the commentary on epigenetic inheritance can be, take the 2017 article from Culture Whiz ‘Genetic Determinism Debunked’. After waxing lyrical over the power of epigenetic effects, the author is forced to admit that epigenetic effects “can also be very readily reversed”, citing the same study he used to originally hype up the effects.

I don't like the quality of the comments gainsaying your claims, but I will say that if I understand your claims correctly, you are killing a bad idea (ie, that there exists even a scintilla of evidence for multi-generational, germline-stable epigenetic inheritance of psychologically traits) and then claiming that doing so clears the room of any possibility that epigenetics play a role in human inheritance, particularly in intergenerational inheritance which you seem (again, correct me if this is a wrong assumption) to conflate with transgenerational inheritance. In effect, you seem to dismiss the possibility of any biologically-mediated intergenerational influence that isn’t SNP-based.

Setting aside that this would be wholly anti-adaptive (and thus we should expect some degree of intergenerational epigenetic influence a priori), robust evidence exists that parental physiological health at conception materially affects offspring phenotype (the correct comparator here would be between-pregnancy conditioning, not within-pregnancy variance on chorion state). Non-epigenetic mechanisms play a role here, but not solely: the instrumental factors are gamete quality and selection, prenatal hormonal and metabolic environments (both paternal and maternal), and--crucially--early embryonic epigenetic initialization (epigenetic states don’t need to persist to matter; they only need to bias early developmental trajectories in a path-dependent manner. Those early cleavage stages determine neural stem pools, placental metabolic efficiency, and the molecular charpente of lineage allocation). All of the above mechanisms are intergenerational, not transgenerational (bc 2x epigenetic resetting and wash-out does obviously occur), and do not violate Mendelian genetics. You can rightly view epigenetics in this frame as a developmental amplifier, not a hereditary archive -- epigenetic in process but not Lamarckian (or neo-Lamarckian, or whatever) in inheritance.

In the 1950s and 1960s China went through an episode of mass starvation followed by the chaos of the cultural revolution. Does that mean most Chinese have inherited trauma. Doesn't seem like it.