Advanced Placement: The Next Target in the Assault on Merit?

A bastion for intellectually precocious youth is under assault by equalitarians...

Written by April Bleske-Rechek.

Note: Opinions, interpretations, and conclusions are those of the author and should not be attributed to the College Board or any other institution. Portions of this article were presented in July, 2023 at the annual conference of the International Society of Intelligence Research in Berkeley, CA.

The Advanced Placement (AP) program began in 1952 when a small number of elite U.S. high schools and universities piloted an educational opportunity in which students could take college coursework while still in high school. In 1954, the first set of common exams were given to 532 students in the participating high schools, and identical exams were taken by first-year students in the participating colleges. The pilot was considered a success when the high school students performed comparably to the college students. The College Board (home of the SAT) agreed to continue the program, explicitly designating it to provide intellectually rigorous, college-level educational choices to able high school students.

Thus began the expansion of the Advanced Placement program. It expanded to more than 22,000 students by the early 1960s. But by the late 1960s and early 1970s, the critics accused the program of being elitist and anti-egalitarian because it lacked racial and socioeconomic diversity among participating students and schools. The College Board responded by designating a new purpose for AP: expand educational opportunities and improve college readiness for all, especially historically disadvantaged youths. Since then, the AP program has engaged in ever-increasing efforts to serve more students from marginalized backgrounds while simultaneously working to maintain its reputation as the gold standard provider of college-level academic challenges during high school.

Today, the AP program offers over 35 courses spanning the arts and humanities, languages and cultures, social sciences, and STEM disciplines. Over two-thirds of public high schools in the U.S. offer one or more AP courses. In 2021, more than 2.5 million high school students took more than 4.5 million exams, which were scored by tens of thousands of educators. Of those exams, 56% earned a qualifying score (a three or above on the 5-point scale).

Recently, I obtained data from the College Board on AP participation and performance from 1996 to 2022 (alternate years) for various well-known AP courses. These data fill out the more recent history of AP. The program continued to expand from the mid-1970s through the 1990s, and as the figure below shows, growth in rates of AP participation exploded from 1996 to 2018. That growth was interrupted in 2020 by COVID-19, with lingering effects into 2022 for most but not all of the courses for which I obtained data.

Like any educational program, the AP program has its critics, but it is highly regarded by many educators, students, and parents for several reasons.

First, AP courses challenge high-achieving students. Effective teaching requires tailoring the learning environment and instruction to each child’s specific needs and learning capacities, and the massive variation among students within any grade - in intellectual abilities, developed knowledge and skills, socio-emotional maturity, and character traits - means that some students will need and want acceleration options such as (but not limited to) AP courses. In the U.S., where a minimal fraction of every educational dollar is earmarked for gifted education, AP courses provide advanced academic material to high-achieving high school students. Research has shown that, as adults, intellectually gifted students look back with gratitude on the intellectual challenge and escape from boredom their AP courses provided during high school.

Second, the program is reliable and valid. Although AP courses vary widely in their specific content and cognitive demands, each course is developed and maintained by a carefully selected team of College Board staff, high school teachers, and college faculty who share a common goal of providing students with a challenging yet structured college-level learning experience while they are still in high school. Research on AP exam development and the reliability and validity of AP exam scores has repeatedly shown that the tests are developed and revised by professional standards. As a college faculty member involved with one AP course since 2016, I have seen the care that goes into rubric development and reader (scorer) training; the intensive and sometimes contentious process of selecting benchmark papers; the massive efforts leaders undergo to ensure that each exam is scored reliably and fairly; and the admirable and enduring commitment of high school teachers and college faculty alike to score every single student’s work according to a standard rubric.

Third, AP provides a way for students to get a head start on college. Students who pass the standard AP exam in a subject area are often eligible to acquire college credits. By some estimates, more than 80% of four-year colleges in the U.S. offer credits or advanced standing on the basis of qualifying or high AP exam scores. The top motive of students in AP classes is to acquire college credit. Indeed, it is not uncommon for students to enter college with sophomore status because they have scored well on multiple AP exams.

Fourth, AP provides a way for students to stand out from other students. Differences in performance levels on the AP exams are essential because some colleges and universities will only allow course credit if students earn the top score of 5. Selective colleges and universities that do not allow course credit for AP exam scores still look at those AP scores when making admissions decisions.

With all that the AP program has to offer, and with so many students nationwide involved, why might the AP program be next in line in the attack on merit? Despite advances in access to AP, there are still persistent gaps in participation in AP, and, more importantly, there are robust group differences in performance on the end-of-year AP exams. For people committed to equalitarianism (sameness), disparities of any kind are unsavory. For people who subscribe to the beliefs underlying critical social justice (or what Tim Urban has labeled social justice fundamentalism), group disparities in achievement are attributed entirely to discrimination. From that perspective, the response would be to dismantle the system revealing the skills gaps rather than address the skills gaps. But more on that later.

The Sex Differences

It is probably not well-known because it goes against a perception of pervasive misogyny that, on the whole, females have been over-represented among AP examinees since the early 1990s. In the 2022 data I received from the College Board, for example, females took most exams in nearly all the heavily populated courses: 67% in Psychology, 63% in English Language and English Literature, 62% in Biology and Spanish Language, 55% in U.S. History, and 53% in Statistics and Chemistry. The sex differences that ruffle feathers, however, are that females continue to be under-represented in Economics (macro; 47%), Physics (around 40%), and especially Computer Science (about 25%) – despite concerted efforts on behalf of the College Board. These sex differences are not surprising given cross-cultural and cross-generational differences between males’ and females’ interests, aptitudes, and vocational choices, but they are unacceptable to those who view gender parity in AP STEM courses as a mechanism for achieving equal representation of the sexes in the financial sector and STEM professions.

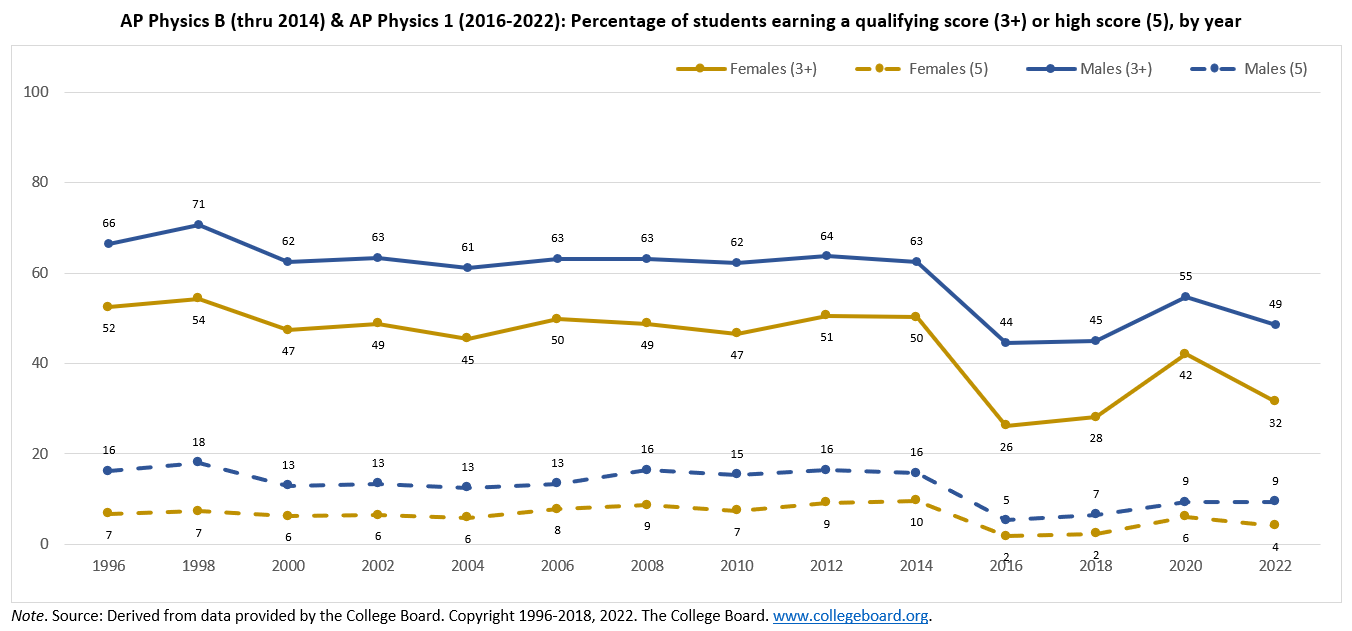

Further, males earn higher scores than females on many of the most cognitively demanding AP exams, a pattern observed in older data as well. In the data I obtained from the College Board, males scored higher than females in Biology, Calculus AB, Chemistry, Computer Science A; English Language and Composition, Macroeconomics, Physics (B, 1 & 2, Electricity & Magnetism, Mechanics), Psychology, Statistics, U.S. Government, U.S. History, and World History; females and males scored similarly in English Literature; and females scored higher than males in Art History, Spanish Language, and Spanish Literature.

Worse still, some of the exams with the largest sex differences in performance are those relevant to the financial sector and STEM. For example, even in courses like Chemistry, where females now take more of the exams than males, males are more likely than females to earn a qualifying score, and they are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to earn a high score (i.e., a 5). The pattern is similar for Macroeconomics and Physics.

On a positive note, though, the sex difference in performance on the Computer Science A exam has decreased over the past decade. As shown below, performance on the exam has improved for both sexes over time, but more for females than males. That said, if females comprise only 25% of Computer Science A examinees, fewer high-performing female than male students are in the pipeline.

The Race/Ethnicity Differences

There also are race/ethnicity differences. Although the availability of AP courses has expanded tremendously over time, there is no equal participation – i.e., enrollment – in AP across racial groups (nor across social classes). Moreover, these gaps have endured even as states have incentivized AP participation through various strategies, such as weighting grades for AP courses, requiring public schools to provide AP courses, using AP participation as a school/teacher accountability metric, subsidizing AP testing fees, and funding attendance of teacher trainings.

The figure below shows the percentage of exams taken by students from four primary racial/ethnic groups each year for the courses for which I obtained data. The population of students engaging with AP has diversified. Asian/Asian American students have consistently been, and increasingly are, over-represented among AP examinees. (They are particularly over-represented in Chemistry, Physics, and Computer Science.) White students are now under-represented among examinees relative to their prevalence in the general population. Hispanic/Latino students are on par with their representation within the population. Still, they are substantially over-represented only in Spanish Language and Spanish Literature and substantially under-represented in STEM courses. Finally, although participation rates have increased over time for Black/African American students, they remain considerably under-represented among AP examinees for all courses.

Every AP exam has a different score distribution, as the exams differ in their demand on general cognitive ability; however, group differences in performance are stark in all courses. For example, the figure below shows the percentage of students earning a qualifying (or “passing”) score in one of the most popular AP courses, English Language and Composition. In the most recent year, 2022, more than 7 of 10 Asian students earned a qualifying score, whereas about 6 of 10 White students and only 3 of 10 Hispanic/Latino and Black students did.

The figures here do not display the percentage of exams scoring a five broken down by racial group, but the disparities are large at that level. In English Language and Composition in 2022, 19% of Asian students scored a 5, followed by 11% of white students, 4% of Hispanic/Latino students, and 3% of Black students.

The group gaps are similar in STEM courses. The figure below shows pass rates for Computer Science A from 1996 to 2022. As shown in the figure, pass rates have improved over time more for Asian students than other student groups. Looking beyond the pass rates, in 2022, over one-third of Asian students earned a five on the exam. Just 25% of White students, 13% of Hispanic/Latino students, and 7% of Black students earned the same.

Calculus AB is another popular STEM course. The figure below shows pass rates for that course, where Asian and White students are consistently 1.5 to 2 times more likely than Hispanic/Latino and Black students to earn a qualifying score. In 2022, 30% of Asian students earned a 5, followed by 20% of White students, 10% of Hispanic/Latino students, and 7% of Black students.

The figure below shows a similar pattern for Chemistry: White students are more than twice as likely, and Asian students are more than three times as likely as Black students to earn a qualifying score. In 2022, 20% of Asian students earned a five on the exam, which was over twice the rate of White students (9%), five times the rate of Hispanic students (4%), and ten times the rate of Black students (2%).

The same group pattern occurs even in Spanish Literature. Although 80% of participating students are Hispanic/Latino, Asian and White students are likelier than Hispanic/Latino (and Black) students to earn a qualifying score. In 2022, 23% of Asian examinees earned a 5, followed by 12% of White students, 6% of Hispanic/Latino students, and 4% of Black students.

Additional Considerations

The data reported above should be considered alongside other important findings about AP. These additional findings reveal that AP exams function just like other standardized tests such as the SAT/ACT.

1. Differential access to AP is not a robust explanation for differential participation (or enrollment) in AP. For example, in various states, most students across racial/ethnic groups attend a school that offers AP courses. It is also a well-kept secret (because so many reports fail to isolate Asian students’ rates of AP participation) that Asian students in multiple states are just as likely as Black and Hispanic students to come from low-income backgrounds. Yet, they enroll in AP at higher rates. Instead, the best explanation for continued differential participation in AP is differential academic preparedness: Racial and income-based differences in AP course-taking are vastly diminished and sometimes reversed after students’ pre-high school academic achievement scores have been accounted for.

2. Even upon enrollment in AP courses, students are not generally required to take the end-of-year exams. Some states and districts give performance bonuses to students and teachers (e.g., $50-$100 for each qualifying score), but those incentives do not improve rates of AP exam-taking, nor do they improve exam performance. The exam score distributions shown above are from students who decide to take the exams, estimated to be 50-60% of students for all racial groups.

3. Performance in specific high school courses predicts how well students do on AP exams, as does overall High School Grade Point Average (HSGPA). However, students’ math and verbal reasoning abilities, as assessed by the PSAT, are far better predictors of performance on the exams than are high school grades.

4. The number of AP courses students take does not predict how they fare in college. Also, differences in academic outcomes for those who enroll in AP but don’t take the exam and those who take the exam but do not pass are minimal. In the words of Dougherty and Mellor (p. 220), “There is little evidence that simply increasing the number of students taking AP courses will have an impact on college graduation rates if students do not demonstrate mastery on the exams.”

5. Students’ AP exam performance predicts how they do in college. Students who demonstrate mastery of the AP exams are also likely to do well in college. In the same way that students’ pre-high school academic achievement scores predict their enrollment in AP courses and students’ PSAT scores predict their subsequent AP exam scores, students’ AP exam scores predict their subsequent college success.

6. As is the case with the data on SAT/ACT scores and academic outcomes, the data relating AP exam participation and performance with academic outcomes are all based on correlational research. No study thus far has been able to use a gold standard design, the randomized controlled trial, to test the causal effect of mastering AP coursework on subsequent achievement. A variety of psychological attributes, in addition to cognitive ability/academic readiness - such as persistence, achievement motivation, and intellectual curiosity - are confounding factors that surely contribute to both scoring well on AP exams and doing well in college.

Concerns for the Future of AP

In 2008, the National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) called for admission counselors, especially those at selective colleges and universities, to put more emphasis on AP (and International Baccalaureate) exams and less on SAT/ACT scores. At that time, the SAT/ACT had long been criticized as biased and unfair because of group differences in scores. The NACAC report reasoned that AP exams have closer ties to curriculum than do the SAT and ACT (although this is undoubtedly the case, at least for the SAT, it is also the case that AP exam performance is more highly correlated with standardized test scores than with high school course grades). Admission counselors consider AP exam scores – even those colleges that do not offer course credit still attend to AP coursework and exam scores to differentiate among applicants.

Since 2008, the SAT and ACT have come under further attack despite the tremendous weight of evidence supporting their psychometric validity for all groups. Many colleges and universities have gone test-optional or test-free in their admission process. This movement away from the SAT/ACT leaves AP exams as the last man standing in the world of standardized assessments to compare college applicants. I worry the AP program, because of the group differences in exam score distributions, will soon be scrutinized by many people – people who are less interested in AP’s original intent of providing college-level rigor to students who are ready for it and far more interested in the degree to which AP is succeeding at improving college readiness for all.

To continue to push “AP for all” is irrational given what is known about students’ math and reading skills upon entry to high school. For example, the most recent data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress show that 62% of Black students enter high school scoring below basic in math, and nearly half (47%) enter high school scoring below basic in reading. The percentages are only slightly better for Hispanic students (51% and 39%) and still worrisome for White students (26% and 18%). These are not the levels of academic readiness that enable students to thrive in an AP classroom. (In fact, one must consider the possible adverse effects, emotional and otherwise, for any given student of any racial identity of being in an AP classroom in which the intellectual demands far surpass their academic preparation.) An effective approach to preparing all students for college-level material would entail recognizing, acknowledging, and addressing skills gaps that exist well before students arrive in an AP classroom. This is undoubtedly a laudable goal.

However, the pull of social justice fundamentalism in educational institutions is substantial. When it becomes clear that achieving equal outcomes on AP exams is as unlikely as achieving equal outcomes on the SAT, the AP program will be tarred as irredeemably racist, just as the SAT has been. Perhaps the AP program would be revamped to be college preparatory rather than college level. Still, I doubt it. And I worry that the AP program will instead be dismantled altogether. In the words of Heather MacDonald in her book When Race Trumps Merit (p. 28), when an academic skills gap is exposed, “it is time to break up the objective yardsticks that measure it.”

In the U.S.’s failing educational system, AP courses are one of the only options commonly available to intellectually precocious youth who otherwise endure day after day of what often feels mundane and stifling. If AP loses out in the battle between commitments to equalitarianism and excellence, we as a nation will simultaneously demonstrate a lack of commitment to developing our nation’s intellectual talent and a lack of respect for our meritocratic ideal of providing every student the particular kind of educational opportunities that best enable them to develop to their full potential.

April Bleske-Rechek is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire.

Consider supporting Aporia with a $6.99 monthly subscription and following us on Twitter.

Great article. FYI, elite private schools are also eliminating AP courses. They argue that their own classes are more rigorous and avoid teaching to the test.

In reality, it's just another way that academically talented, middle class white and Asian boys have the deck increasingly stacked against them. Eliminating standardized testing, AP exams, honors classes, etc. means that there are fewer and fewer way to objectively demonstrate excellence and potential. These kids don't have "lived experience" or huge donations to fall back on when applying to college.

The war on merit continues and the casualties keep piling up.

Here in our largest public school district—majority Hispanic, proficiency on math and reading was 13 and 22 percent. This figure gets more dismal decade by decade as the Whites leave for charter schools and the district become more Hispanic. Here to, AP in public institutions is criticized for showing differences among racial groups. I suspect such testing will be eliminated as well in the public sector as it is deemed too White—and too revealing.

Such does no one any good. My experience has been the AP course work was taken for two benefits: strong instructional rigor, and college cost savings. I don’t think the cost savings aspect is nearly as important as the instructional rigor aspect. High school, particularly public HS, has become a joke. Far too many college freshman get slammed when they enter their first year of college classes. Anything we can do to prepare them in how to survive a college level milieu seems a productive use of resources.

Another thing we need to look at is simple mastery of college prerequisites *before* admission. In this town we have a top 20 research university. Last report, 40% of the entering student enrollment was taking “remedial” classes! Folks, “fogging a mirror” does not fulfill college prerequisites. Time to admit to ourselves, college is not for everyone.