Why are women lighter-skinned than men?

Skin color was gendered before it was racialized.

Written by Peter Frost.

Women are the “fair sex” because their skin has less melanin and less hemoglobin. They thus look pale in comparison to the darker and ruddier color of men. This difference has a hormonal basis, as shown by studies of normal, castrated and ovariectomized individuals, as well as by a digit ratio study (Edwards & Duntley, 1939; Edwards & Duntley, 1949; Edwards et al., 1941; Manning et al., 2004).

The differing skin tones of men and women were once the main source of variation in skin color within any one group of people. Thus, for most of history and prehistory, darker skin was associated with men and lighter skin with women (Frost, 2010; Frost, 2011; Frost, 2023; van den Berghe & Frost, 1986).

The human mind still uses skin color subconsciously to tell male and female faces apart, especially if face shape is poorly visible. The main criterion is hue – the brownness and ruddiness of the skin. If the face is too far away or the lighting too dim, the mind will switch to the more time-consuming but accurate criterion of luminosity – the brightness of the skin. Facial color is thus perceived through a mechanism that served originally to distinguish between men and women, even though we increasingly live in environments where skin color differs much more between people of different geographic origins (Dupuis-Roy et al. 2009; Dupuis-Roy et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2015; Nestor & Tarr, 2008a; Nestor & Tarr, 2008b; Tarr et al., 2001; Tarr et al., 2002; Yip & Sinha, 2002).

Therefore, an observer will unthinkingly treat darker faces as male and lighter faces as female. This has been shown by responses to facial color in several studies:

Make pictures of faces more attractive by varying their skin color. Male faces are made darker and ruddier than female ones (Carrito et al., 2016).

Assess the skin color of faces. Female faces are judged to be lighter-skinned than male ones, even though most of the participants deny that skin color differs between men and women (Carrito & Semin, 2019).

View several faces (of identical skin color). Then use your memory to identify each of them from a row of faces (which vary only in skin color). Participants respond by choosing lighter versions of the original female faces and darker versions of the original male faces, even though the original faces were all the same color (Carrito & Semin, 2019).

Even inanimate objects are unthinkingly gendered in the same way:

Identify personal names by gender. Names are identified faster by gender when male names are presented in black and female names in white (Semin et al., 2018).

Classify briefly appearing blobs by gender. Black blobs are classified predominantly as male and white blobs as female (Semin et al., 2018).

Observe light and dark objects, while having your eye movements tracked. Observation is longer and fixation more frequent when a dark object is associated with a male character and a light object with a female character (Semin et al., 2018).

Evolution of women’s lighter skin

This mental mechanism may help the observer not only to distinguish between men and women but also to respond in a gender-appropriate manner. Such a function is suggested by the evolutionary trajectory that led to women becoming lighter-skinned.

A lighter color is one of several infant characteristics that the adult female body seems to mimic, including a smaller nose and chin, smoother and more pliable skin and a higher pitch of voice. This is what ethologist Konrad Lorenz called the Kindchenschema – a set of visual, tactile and auditory cues that identify an infant to an adult, who responds by feeling less aggressive and more willing to defend and nurture. In a word, the infant seems “cute” (Frost, 2010, pp. 134-135; Lorenz, 1971, pp. 154-164).

An infant’s lighter skin is especially noticeable in dark-skinned human groups, and also in many primate species. Langurs, baboons and macaques are born pink and later darken, becoming almost black in adulthood. Their fur, too, is lighter at birth and darkens with age. The lighter color seems to make nearby adults more caring and protective. As the infant darkens with age, its mother no longer seeks it out to hold it (Alley, 1980; Alley, 2014; Booth, 1962; Guthrie, 1970; Jay, 1962).

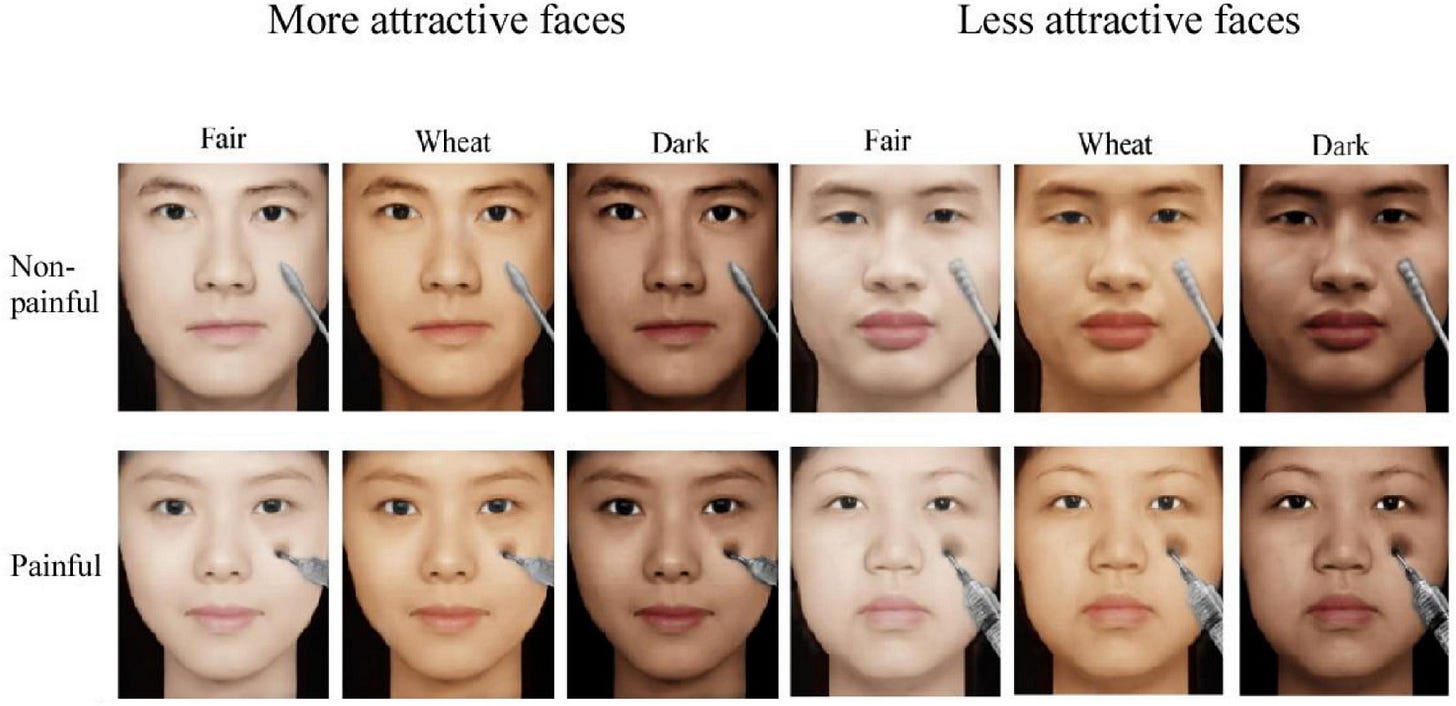

Emotional response to light skin has been studied by researchers in China, where minor differences in skin color do not have the same social meaning as they do elsewhere. Participants were shown a series of attractive or unattractive Chinese faces that varied in skin color and which seemed to be either in pain (with a syringe needle sticking into a cheek) or not in pain (with a Q-tip touching a cheek). For each face, the participant had to judge whether it was experiencing pain. Reaction time was also measured, as was brain activity on an electroencephalogram (EEG).

When the faces were attractive and seemingly in pain, the lighter ones were judged to be suffering more than the darker ones. Furthermore, reaction time was shorter, and the EEGs showed a higher level of empathy. But there was no difference in response when the faces were unattractive. Only when the faces were both light-colored and attractive did the apparent pain trigger an increase in empathy (Yang et al., 2022). This emotional response may be contingent on both lighter skin tone and facial attractiveness because the latter encompasses other “cute” characteristics of the Kindchenschema.

The increase in empathy could therefore be an evolved response to seeing an infant or a woman in danger. In both situations, the visual identifier would be lighter skin. Darker, ruddier skin would conversely trigger less empathy.

General perceptions of male redness

Male skin color has two components: 1) increased redness, due to greater blood circulation in the skin; and 2) decreased luminosity, due to higher concentration of melanin. Let’s begin with the first component. How do people perceive increased redness on a male body? This question has inspired much research since a high-profile finding two decades ago.

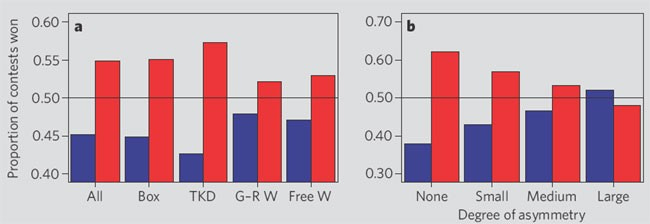

At the 2004 Olympic Games, athletes won more often with red uniforms than with blue ones. In man-to-man contests of boxing, taekwondo, Greco-Roman wrestling and freestyle wrestling, the contestants with red uniforms won 16 out of 21 rounds. Those with blue uniforms won only 4 rounds. The red uniforms seem to have been more intimidating, perhaps because dominant males have more testosterone and, hence, a ruddier facial and corporeal color (Hill & Barton, 2005). This finding has since been corroborated by two other studies, which likewise conclude that red clothing makes a man seem more dominant and threatening (Feltman & Elliot, 2011; Wiedemann et al., 2015).

Even alone, without a male body, redness seems to make the observer more cautious, more compliant, more aggressive or more submissive. This is the conclusion of several studies for a variety of tasks:

Identify the color of words on a computer screen. Men take longer than women to answer when the words are in red (Ioan et al., 2007).

Identify the incorrect idiom from a list of idioms. The error rate is higher when the idioms are in red than when they are in blue (Shi et al., 2015).

Exercise on a stationary bicycle in a red environment. Covered distance and heart rate are lower in a red environment than in a green or gray one, while enjoyment is higher in a green environment than in a red one (Briki et al., 2015).

Make bids at an auction and make price offers during negotiations. A red background causes higher jumps in bids at an auction and lower offers during negotiations (Bagchi & Cheema, 2012).

Respond to the message in an advertisement. Compliance with the message is higher when shown against a red background (Kareklas et al., 2019).

The redness effect varies with context. It is weakest when redness is presented alone or when it coexists with a much stronger advantage; for example, English soccer teams have the same home advantage with or without red shirts (Allen & Jones, 2014). The effect is progressively stronger when redness is associated with a facial photo, rather than a simplified drawing of a face, and stronger still when the face is attractive (Buechner et al., 2014; Pazda et al., 2023; Schwarz & Singer, 2013; Wen et al., 2014; Young, 2015).

Redness also affects the perceived passing of time, the effect being greater for men than for women. When people are shown either a red screen or a blue screen for the same length of time, they perceive the red screen as lasting longer than the blue screen. This overestimation is greater for men than for women. People also react faster to the red screen than to the blue screen, and the reaction time correlates with their tendency to overestimate red-screen duration. It seems that “the arousal induced by red increases the speed of the internal clock” (Shibasaki & Masataka, 2014).

Finally, redness can help distinguish between facially similar emotions, such as anger versus disgust, surprise versus fear and sadness versus happiness (Thorstenson et al., 2019a; Thorstenson et al., 2021). When faces are viewed against a red background, people take less time to identify a face as angry than they do to identify it as happy or fearful (Young et al., 2013).

Lack of redness, such as when a face turns pale with fright, has the reverse effect. It appeases the observer and de-escalates conflict. When people are asked to rate their propensity for turning pale, the highest scores come from those who fear blood and injury. Women score higher on average than men (Drummond, 1997).

What about when a face turns red with embarrassment? As with anger, blushing serves to keep the observer at a distance, being a sort of controlled anger (Drummond, 1997). It is usually motivated by embarrassment about a social transgression. If a person blushes while making an apology, the observer will more likely perceive it as sincere and be more forgiving (Thorstenson et al., 2019b). Blushing seems to be heritable. Darwin cited the case of a father, mother and ten children, “all of whom, without exception, were prone to blush to a most painful degree” (Darwin, 1872, p. 312).

General perceptions of male darkness

We now turn to the second component of male skin color. How do people perceive decreased luminosity on a male body? The relevant literature is mostly about color symbolism in different cultures.

The ancient Greeks believed that a woman’s light color incarnated her “helplessness and need of protection” and a man’s dark color his “courage and the ability to fight well” (Irwin 1974, p. 121). A brave man had a “black rump”, and a coward a “white rump.” The same mental association was projected onto the internal organs and ultimately onto the soul. A “black heart” denoted strong emotions, and a “white heart” indifference or a refusal to act. A coward had a “white liver”, a metaphor that survives in our expression “lily-livered” (Irwin 1974, pp. 129-155).

Cross-culturally, whiteness evokes weakness and blackness strength (Gergen 1967, p. 397; Osgood 1960, p. 165). According to a Turkish study, blackness is associated with power, fear, courage and eternity, and redness with courage, enthusiasm, fun and anxiety. In contrast, whiteness is associated with cleanliness, honesty, peace and hope (Demir, 2020). A cross-cultural study with participants from China, Germany, Greece and the UK found that “BLACK and RED evoked more consistent colour–emotion association patterns than other colour terms. BLACK and RED colour terms were also more commonly associated with strong emotions, and evoked a larger number of associated emotions than many other colour terms” (Jonauskaite et al., 2019).

A similar pattern emerged in a study of elderly rural French Canadians. Participants perceived darker, ruddier men as being stronger and more virile in both physique and character. If a man was too dark, he would be considered quick-tempered, arrogant and malicious. Women were expected to be fairer-skinned, although their lighter color was likewise associated with weakness of physique and character (Frost, 2010, pp.149-152).

Female perceptions of male redness/darkness

We now turn to gender-specific perceptions. How do women perceive increased redness on a male body?

In one study, female participants were presented with male faces that had different levels of ruddiness. They associated high levels with aggression, medium levels with dominance and low levels with attractiveness (Stephen et al., 2012). In a second study, female participants were presented with images of men against differently colored backgrounds and in differently colored clothing. They judged the men to be more attractive when viewed against a red background and in red clothing. This effect was confined to sexual attractiveness and did not change a man’s overall likability (Elliot et al., 2010). These findings seem to be contradictory: male attractiveness was associated with a low level of redness in one study and with a high level in the other. The contradiction might lie in the way the word “attractiveness” was understood, perhaps being construed in an aesthetic manner by the women of the first study, and in a sexual one by those of the second.

How do women perceive decreased luminosity on a male body? This perception seems to be hormonally influenced, as shown by the responses of female participants to male faces in two studies:

Choose between two male faces that differ slightly in color. The darker face is more often preferred during the first two-thirds of the participant’s menstrual cycle than during the last third, although the lighter face is always the majority preference. During the first two-thirds of the cycle, the level of estrogen is high in relation to the level of progesterone (which acts as an anti-estrogen). During the last third, the ratio is reversed, with estrogen being low relative to progesterone. There is no cyclical change in preference if the participants view female faces or are taking oral contraceptives (Frost, 1994).

View male faces during a brain MRI. There is a stronger neural response to masculinized male faces than to feminized ones, and the strength of response correlates with the participant’s estrogen level across the menstrual cycle. In a personal communication, the lead author stated that the faces were masculinized by making them darker and more robust in shape (Rupp et al., 2009).

An estrogenic effect is further suggested by a study of preschool children:

Choose between two dolls that differ slightly in skin color. Adiposity is measured by body mass index and by thickness of subcutaneous fat. Among either boys or girls below three years of age, body fat is greater in those choosing the darker doll than in those choosing the lighter doll. In that age range, estrogen is produced mostly in fatty tissues (Frost, 1989).

To some extent, the above preferences can be triggered by red or dark clothing, as shown by a study of preferences for men or women dressed in blue, green, yellow, red, white or black. Female participants prefer men dressed in red or black. The same colors are preferred when male participants judge either men or women. But neither red nor black is preferred when female participants judge women (Roberts et al., 2010).

Male perceptions of female redness/darkness

How do men perceive increased redness on a female body? Women with red clothes seem more attractive to men (Elliot & Niesta, 2008), but this effect is conditional. A woman with red clothes seems more attractive if she is already attractive, but not if she is masculine, older or unattractive (Pazda et al., 2023; Schwarz & Singer, 2013; Wen et al., 2014; Young, 2015). This effect is confined to sexual attractiveness and does not affect a woman’s overall likability (Wen et al., 2014). It seems that redness intensifies a man’s interest in a woman; hence, if there is nothing of interest to begin with, there is nothing to intensify.

How do men perceive decreased luminosity on a female body? When male participants are shown pictures of lighter-skinned and darker-skinned women, they judge the two groups to be equally attractive, but their eye movements tell another story: they view the lighter-skinned women for a longer time than the darker-skinned ones (Garza et al., 2016). Given that the two groups of women arouse the same degree of sexual interest, male response to darker women must be briefer and more intense, with the same level of interest concentrated in a shorter time.

This interpretation is consistent with popular culture. In English novels from the Victorian era, “the dark lady” is portrayed as an “impetuous,” “ardent” and “passionate” player in short-lived romances (Carpenter, 1936, p. 254). In French and German novels from that era, “the love incarnated by les brunes appears as the conceptual equivalent of a devouring femininity, thus making them similar to the mythical figure of Lilith.” (Atzenhoffer, 2011, p. 6). For one French writer, men who love les brunes “are generally taken by a passion that is more violent, more demonstrative and more domineering, but also less profound, less tender and less durable” (Briot, 2007).

Popular culture attests to a similar effect of increased female redness on male arousal. The “lady in red” is a femme fatale:

In literature, red has repeatedly been associated with female sexuality, especially illicit sexuality, most famously in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s classic work The Scarlet Letter. Likewise, in popular stage and film, there are many instances in which red clothing, especially a red dress, has been used to represent passion or sexuality … Red is paired with hearts on Valentine’s Day to symbolize romantic affection and is a highly popular color for women’s lingerie. Red has been used for centuries to signal sexual availability or “open for business” in red-light districts. Women commonly use red lipstick and rouge to heighten their attractiveness, a practice that has been in place at least since the time of the ancient Egyptians (Elliot & Niesta, 2008)

But why, then, did women evolve lighter skin?

In sum, a dark, reddish color excites the observer much more than a lighter one. The effect is stronger if the dark or reddish color is associated with a human body and, even more so, with an attractive human face. Furthermore, it is as strong for a man observing a woman as it is for a woman observing a man. This excitation can increase sexual arousal, although the level of arousal seems to decline after an initial spike – perhaps because higher levels are exhausted more rapidly.

If a dark, reddish color increases sexual arousal not only when a woman is observing a man but also when a man is observing a woman, why, then, did women become less dark and less ruddy than men? Wouldn’t sexual selection have favored darker, ruddier women? For that matter, why should there be any sex difference in skin tone?

Perhaps the need to survive and procreate favored those women who could not only arouse sexual interest but also maintain it over the longer term. That goal would be incompatible with concentrating such interest within a briefer but more intense interval. In this evolutionary scenario, lighter female skin was favored not because it intensified male sexual interest but rather because it stabilized the pair bond more effectively through a decrease in male aggressiveness and an increase in male provisioning – by mimicking the Kindchenschema. This is sexual selection in a broad sense. The pressure of selection extends beyond the moment of mate choice to encompass the much longer period of cohabitation after mating.

Peter Frost has a PhD in anthropology from Université Laval. His main research interest is the role of sexual selection in shaping highly visible human traits, notably skin color, hair color and eye color. Other research interests include gene-culture coevolution. Find his newsletter here.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

References

Allen, M. S., & Jones, M. V. (2014). The home advantage over the first 20 seasons of the English Premier League: Effects of shirt colour, team ability and time trends. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(1), 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2012.756230

Alley, T. R. (1980). Infantile colouration as an elicitor of caretaking behaviour in Old World primates. Primates, 21(3), 416-429. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02390470

Alley, T.R. (2014[1986]). An ecological analysis of the protection of primate infants. In V. McCabe & G.J. Balzano (Eds.) Event Cognition: An Ecological Perspective. Routledge.

Atzenhoffer, R. (2011). Les hommes préfèrent les blondes. Les lectrices aussi. Effet de psychologie, horizons idéologiques et valeurs morales des héroïnes dans l'œuvre romanesque de H. Courths-Mahler. Colloque national (CNRIUT), Villeneuve d'Ascq, 8-10 juin 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20210921193948/http://cnriut09.univ-lille1.fr/articles/Articles/Fulltext/10a.pdf

Bagchi, R., & Cheema, A. (2013). The effect of red background color on willingness-to-pay: the moderating role of selling mechanism. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5), 947-960. https://doi.org/10.1086/666466

Booth, C. (1962). Some observations on behavior of Cercopithecus monkeys. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 102(2), 477-487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13654.x

Briki, W., Rinaldi, K., Riera, F., Trong, T. T., & Hue, O. (2015). Perceiving red decreases motor performance over time: A pilot study. European Review of Applied Psychology, 65(6), 301-305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2015.09.001

Briot, E. (2007). Couleurs de peau, odeurs de peau : le parfum de la femme et ses typologies au xixe siècle. Corps, 2(3), 57-63. https://doi.org/10.3917/corp.003.0057

Buechner, V. L., Maier, M. A., Lichtenfeld, S., & Schwarz, S. (2014). Red-take a closer look. PloS one, 9(9), e108111. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108111

Carpenter, F. I. (1936). Puritans preferred blondes. The heroines of Melville and Hawthorne. New England Quarterly, 9(2), 253-272. https://doi.org/10.2307/360391

Carrito, M.L., dos Santos, I.M.B., Lefevre, C.E., Whitehead, R.D., da Silva, C.F., & Perrett, D.I. (2016). The role of sexually dimorphic skin colour and shape in attractiveness of male faces. Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(2), 125-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.09.006

Carrito, M. L., & Semin, G. R. (2019). When we don’t know what we know–Sex and skin color. Cognition, 191, 103972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.05.009

Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London: John Murray.

Demir, Ü. (2020). Investigation of color-emotion associations of the university students. Color Research & Application, 45(5), 871-884. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.22522

Drummond, P.D. (1997). Correlates of facial flushing and pallor in anger - provoking situations. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(4), 575-582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00077-9

Dupuis-Roy, N., Faghel-Soubeyrand, S., & Gosselin, F. (2019). Time course of the use of chromatic and achromatic facial information for sex categorization. Vision Research, 157, 36-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2018.08.004

Dupuis-Roy, N., Fortin, I., Fiset, D., & Gosselin, F. (2009). Uncovering gender discrimination cues in a realistic setting. Journal of Vision, 9(2), 10, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1167/9.2.10

Edwards, E.A., & Duntley, S.Q. (1939). The pigments and color of living human skin. American Journal of Anatomy, 65(1), 1-33. https://doi.org/10.1002/aja.1000650102

Edwards, E.A., & Duntley, S.Q. (1949). Cutaneous vascular changes in women in reference to the menstrual cycle and ovariectomy. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 57(3), 501-509. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(49)90235-5

Edwards, E.A., Hamilton, J.B., Duntley, S.Q., & G. Hubert, G. (1941). Cutaneous vascular and pigmentary changes in castrate and eunuchoid men. Endocrinology, 28(1), 119-128. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-28-1-119

Elliot, A. J., & Niesta, D. (2008). Romantic red: red enhances men's attraction to women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1150. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1150

Elliot, A. J., Niesta Kayser, D., Greitemeyer, T., Lichtenfeld, S., Gramzow, R. H., Maier, M. A., & Liu, H. (2010). Red, rank, and romance in women viewing men. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139(3), 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019689

Feltman, R., & Elliot, A. J. (2011). The influence of red on perceptions of relative dominance and threat in a competitive context. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33(2), 308-314. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.33.2.308

Frost, P. (1989). Human skin color: the sexual differentiation of its social perception. Mankind Quarterly, 30, 3-16. https://doi.org/10.46469/mq.1989.30.1.1

Frost, P. (1994). Preference for darker faces in photographs at different phases of the menstrual cycle: Preliminary assessment of evidence for a hormonal relationship. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 79(1), 507-14. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1994.79.1.507

Frost, P. (2010). Femmes claires, hommes foncés. Les racines oubliées du colorisme. Quebec City: Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 202 p. https://www.pulaval.com/livres/femmes-claires-hommes-fonces-les-racines-oubliees-du-colorisme

Frost, P. (2011). Hue and luminosity of human skin: a visual cue for gender recognition and other mental tasks. Human Ethology Bulletin, 26(2), 25-34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256296588_Hue_and_luminosity_of_human_skin_a_visual_cue_for_gender_recognition_and_other_mental_tasks

Frost, P. (2023). The original meaning of skin color. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, March 20.

Garza, R., Heredia, R.R., & Cieslicka, A.B. (2016). Male and female perception of physical attractiveness. An eye movement study. Evolutionary Psychology, 14(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1474704916631614

Gergen, K.J. (1967). The significance of skin color in human relations. Daedalus, 96, 390-406. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027044

Guthrie, R.D. (1970). Evolution of human threat display organs. In: Dobzhansky, T., Hecht, M.K., & Steere, W.C. (Eds.) Evolutionary Biology, 4, 257-302. New York: Appleton-Century Crofts.

Hill, R., & Barton, R. (2005). Red enhances human performance in contests. Nature, 435, 293. https://doi.org/10.1038/435293a

Ioan, S., Sandulache, M., Avramescu, S., Ilie, A., & Neacsu, A. (2007). Red is a distractor for men in competition. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 285-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.03.001

Irwin, E. (1974). Colour Terms in Greek Poetry. Toronto: Hakkert.

Jay, P.C. (1962). Aspects of maternal behavior among langurs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 102(2), 468-476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13653.x

Jonauskaite, D., Wicker, J., Mohr, C., Dael, N., Havelka, J., Papadatou-Pastou, M., ... & Oberfeld, D. (2019). A machine learning approach to quantify the specificity of colour–emotion associations and their cultural differences. Royal Society Open Science, 6(9), 190741. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190741

Jones, A.L., Russell, R., & Ward, R. (2015). Cosmetics alter biologically-based factors of beauty: evidence from facial contrast. Evolutionary Psychology, 13(1) https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491501300113

Kareklas, I., Muehling, D. D., & King, S. (2019). The effect of color and self-view priming in persuasive communications. Journal of Business Research, 98, 33-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.022

Lorenz, K. (1971). Studies in Animal and Human Behaviour, vol. 2. London: Methuen & Co.

Manning, J.T., Bundred, P.E., & Mather, F.M. (2004). Second to fourth digit ratio, sexual selection, and skin colour. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25(1), 38-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-5138(03)00082-5

Nestor, A., & Tarr, M.J. (2008a). The segmental structure of faces and its use in gender recognition. Journal of Vision, 8(7), 7, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1167/8.7.7

Nestor, A., & Tarr, M.J. (2008b). Gender recognition of human faces using color. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1242-1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02232.x

Osgood, C.E. (1960). The cross-cultural generality of visual-verbal synesthetic tendencies. Behavioral Science, 5(2), 146-169. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830050204

Pazda, A. D., & Elliot, A. J. (2017). Processing the word red can enhance women’s perceptions of men’s attractiveness. Current Psychology, 36, 316-323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9420-8

Pazda, A. D., Thorstenson, C. A., & Elliot, A. J. (2023). The effect of red on attractiveness for highly attractive women. Current Psychology, 42(10), 8066-8073. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s12144-021-02045-3

Roberts, S. C., Owen, R. C., & Havlicek, J. (2010). Distinguishing between perceiver and wearer effects in clothing color-associated attributions. Evolutionary Psychology, 8, 350–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491000800304

Rupp, H.A., James, T.W., Ketterson, E.D., Sengelaub, D.R., Janssen, E., & Heiman, J.R. (2009). Neural activation in women in response to masculinized male faces: mediation by hormones and psychosexual factors. Evolution and Human Behavior, 30(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.08.006

Schwarz, S., & Singer, M. (2013). Romantic red revisited: Red enhances men’s attraction to young, but not menopausal women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.08.004

Semin, G.R., Palma, T., Acartürk, C., & Dziuba, A. (2018). Gender is not simply a matter of black and white, or is it? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 373(1752), 20170126. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0126

Shi, J., Zhang, C., & Jiang, F. (2015). Does red undermine individuals' intellectual performance? A test in China. International Journal of Psychology, 50(1), 81-84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12076

Shibasaki, M., & Masataka, N. (2014). The color red distorts time perception for men, but not for women. Scientific Reports, 4, 5899. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05899

Stephen, I.D., Oldham, F.H., Perrett, D.I., & Barton, R.A. (2012). Redness enhances perceived aggression, dominance and attractiveness in men's faces. Evolutionary Psychology, 10(3) https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491201000312

Tarr, M.J., Kersten, D., Cheng, Y., & Rossion, B. (2001). It's Pat! Sexing faces using only red and green. Journal of Vision, 1(3), 337, 337a. https://doi.org/10.1167/1.3.337

Tarr, M. J., Rossion, B., & Doerschner, K. (2002). Men are from Mars, women are from Venus: Behavioral and neural correlates of face sexing using color. Journal of Vision, 2(7), 598, 598a. https://doi.org/10.1167/2.7.598

Thorstenson, C.A. (2018). The social psychophysics of human face color: Review and recommendations. Social Cognition, 36(2), 247-273. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2018.36.2.247

Thorstenson, C.A., Pazda, A.D., Young, S.G., & Elliot, A.J. (2019a). Face color facilitates the disambiguation of confusing emotion expressions: Toward a social functional account of face color in emotion communication. Emotion, 19(5), 799-807. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000485

Thorstenson, C.A., Pazda, A., & Lichtenfeld, S. (2019b). Facial blushing influences perceived embarrassment and related social functional evaluations. Cognition and Emotion June 23, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2019.1634004

Thorstenson, C.A., McPhetres, J., Pazda, A.D., & Young, S.G. (2021). The role of facial coloration in emotion disambiguation. Emotion, 22(7), 1604-1613. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000900

van den Berghe, P.L., & Frost, P. (1986). Skin color preference, sexual dimorphism and sexual selection: A case of gene-culture co-evolution? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 9(1), 87-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1986.9993516

Wen, F., Zuo, B., Wu, Y., Sun, S., & Liu, K. (2014). Red is romantic, but only for feminine female faces: Sexual dimorphism moderates red effect on sexual attraction. Evolutionary Psychology, 12, 719–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491401200404

Wiedemann, D., Burt, D. M., Hill, R. A., & Barton, R. A. (2015). Red clothing increases perceived dominance, aggression and anger. Biology Letters, 11(5), 20150166. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2015.0166

Yang, D., Li, X., Zhang, Y., Li, Z., & Meng, J. (2022). Skin color and attractiveness modulate empathy for pain: an event-related potential study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 780633. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.780633

Yip, A.W., & Sinha, P. (2002). Contribution of color to face recognition. Perception, 31(8), 995-1003. https://doi.org/10.1068/p3376

Young, S.G. (2015). The effect of red on male perceptions of female attractiveness: Moderation by baseline attractiveness of female faces. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2098

Young, S.G., Elliot, A.J., Feltman, R., & Ambady, N. (2013). Red enhances the processing of facial expressions of anger. Emotion, 13(3), 380–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032471

That was a thoroughly satisfying read. Thanks. My wife, an Asian, was extremely light-skinned when we first married and her skin color has since gradually darkened with age. Looking at old photos of her re-elicits in me exactly the male attitude(s) you describe, however.

I'm curious about the role of vitamin D? (ie fitness selection rather than sexual selection).

I gather animal studies have suggested a link between low vD status during gestation and poor (cognitive) outcomes for their offspring. This seems a feasible mechanism for selection of relatively pale human females.

Perplexity.ai pointed me to an open access 2024 review paper in Nature (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41387-024-00296-0) that recommends vD supplements for pregnant women due to adverse birth (ie noncognitive) outcomes of vD deficiency. The studies reviewed looked at a combined total of 250,569 gestating women.

So, shout this recommendation from the rooftops?

In the Nature review paper discussion it seems to say Low vD status appears to have adverse outcomes for mother and child (during pregnancy and birth) based on weak 'observational' data but with stronger 'RCT' data for a benefit from vD supplements, though the level of benefit is unclear (ie not a strong selective pressure?).

Also, Perplexity.ai pointed me to what seems a pretty good 2017 study from Southern India which found no association between ~400 pregnant mother's vD status (measured once at <30 weeks) and the subsequent child's cognitive performance (at preschool and early adolescence). (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5965666/).