Where did all the geniuses go?

A century ago, the world seemed rife with geniuses. It seems as if genius has been collectivized and that the days of the solitary thinker or creative genius, the great man or woman, have passed.

Written by Joseph Bronski.

A century ago, the world seemed rife with geniuses. Einstein, Bohr, Picasso, Freud, Eliot, Stravinsky, Joyce, Faulkner. A motley assortment of culture-changing visionaries. But today, many lament a lack of comparable figures. Who are the physicists who can compete with Einstein or Bohr? Who are the musicians who can compete with Schoenberg or Stravinsky? Who are the poets who can compete with Eliot or Pound?

It seems as if genius has been collectivized and that the days of the solitary thinker or creative genius, the great man or woman, have passed. Scientific progress is no longer driven by great individuals, but by The People, by tinkerers and experimenters. Thus, almost nobody, even those who are rather educated, can name a single physics Nobel Prize recipient from the last 30 years.

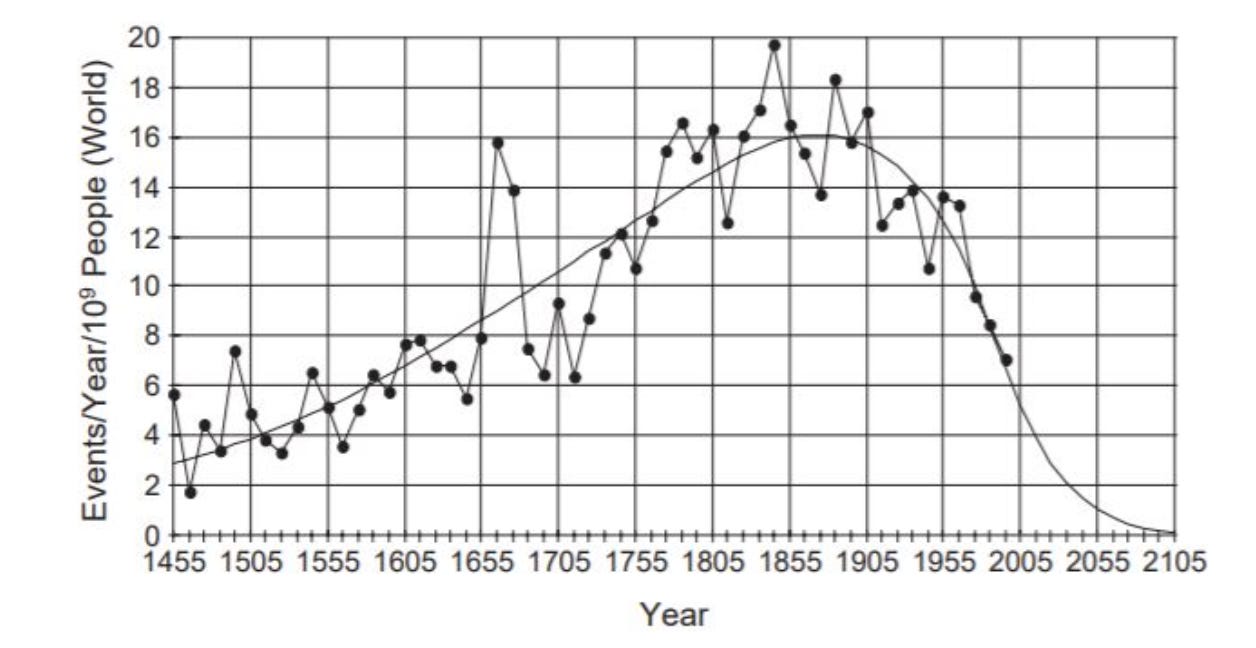

Two immediate causes suggest themselves: fewer geniuses, and less public willingness to recognize and celebrate genius. Some data support the first hypothesis, at least in so far as general intelligence is declining and having high cognitive ability is a precondition for being a creative genius. However, there are countervailing forces, such as more people and more mobility, which allow people to maximize their potential. Thus, this is likely not the predominant cause. Instead, the more important cause is that we are failing to recognize genius.

This is precisely what Darrin McMahon argues in his book Divine Fury: A History of Genius. This history is in fact a conceptual history of the word “genius”, describing assumptions about genius throughout human history.

McMahon argues that in antiquity, the locus of genius was external. For example, Socrates was said to have a demon – he was, simply, possessed by divine fury:

In that respect, at least, this extraordinary man was not all that different from the great majority of his contemporaries, who also believed in spirits hidden and unseen. Invoking daimones as a way to explain the silent forces that moved through their lives, they conceived of these powers as akin to fortune or fate, affecting their actions despite their explicit intentions, for better or for worse. […] Socrates’s own understanding of his daimonion likely drew on these broader beliefs, which were also sustained by widely received legends, myths, and poems. In the verses of Homer, for example, Greeks would have encountered scattered, if conflicting, references to the daimones, which the bard equates on occasion with the gods of Mount Olympus themselves.

Then, in the Christian Middle Ages, the locus moved from pagan drivers to guardian angels:

That redefinition—or what we might call today “rebranding”—had a curious consequence, preserving at the heart of a nominally monotheistic religion the remnants of a polytheistic conception of the world. Alongside God the Father hovered untold legions of little “gods”—never, to be sure, described by Christians as such—but present nonetheless. No wonder that early Christians saw demons everywhere! The whole of the pagan pantheon—from the Olympians to the most insignificant local genius or sprite—was reconceived as the product of mass illusion wrought by the work of conniving spirits.

But during the Renaissance, the modern view began to emerge. Philosophers “substituted the beautiful soul for the angels as the agent of ascent to God … our true genius was the glorious mind, caught up in the rapture of divine embrace.” Thus, the cult of the natural genius was born.

This cult did not go unchallenged. Marx famously wrote that “history repeats itself: first as tragedy, then as farce.” We may now be living through the farce. The tragedy was the egalitarian Reign of Terror, which killed thousands of people.

The Reign of Terror did not last, nor did the egalitarianism that inspired it. The cult of the individual genius saw new life. But that life is again under siege in a new age of widespread egalitarian sentiment. McMahon calls this the age of “the genius of the people.” People have begun to ascribe genius not only to physicists and composers but also to soccer players and boxers — “Genius was no longer confined to the artists, statesmen, and scientists who had long commanded pride of place.”

Everyone has become a genius: “Genius is now everywhere. A 1993 cover story in Newsweek magazine, for example, observed that ‘judging by the hundreds to the thousands of newspaper references to ‘geniuses’ every month, we’re overrun with them.’” If your favorite livestreamer is a genius, the word loses its power to describe Yann LeCun, Geoffrey Hinton, and Yoshua Bengio, three living visionaries who have given us much of the technology and methodology in AI that birthed GPT and other famous, groundbreaking tools. Men like these disappear from a public eye that lacks the capacity to distinguish them from professional Fortnite players.

Is it a coincidence that the mundane have become the genius in the same age that the ugly have become beautiful, in an age filled to the brim with egalitarianism? It is unlikely that the root causes of these phenomena differ. What that cause is exactly remains mysterious – but it can’t hurt to think about what you want genius to mean the next time you use the word.

Is Divine Fury worth reading? The strongest aspect of the book is its tracing of the conceptual evolution of the ideal of genius from antiquity to the present day. McMahon gives scores of anecdotes on how the meaning of genius, once having been associated with external, divine influences, was gradually internalized. It provides the reader with a broad historical context for the understanding of genius.

The weakest part of the book is that it is not data-driven. Anecdotal histories have limited objective utility and mostly serve to help a reader think more deeply about his or her own idea of genius. That said, given my priors about the pagan religiosity of ancient peoples, McMahon’s argument that genius was once considered the product of supernatural influences seems likely to be correct.

It's also worth noting that McMahon's analysis could have been more interesting and wide-reaching if he included a deeper exploration of the idea of genius in different non-Western cultures. What do the Chinese think about genius and how has that changed since the time of Confucius? McMahon doesn’t consider this question.

Despite limitations, Divine Fury is a thought-provoking exploration of the history of the concept of genius. If you are interested in this, I would recommend giving it a read.

Joseph Bronski is a Substacker, Youtuber, Twitterer and researcher interested in human biodiversity, political psychology, and social power. He graduated summa cum laude with a B.S. in computer science in 2023.

Follow us on Twitter and consider supporting us with a paid subscription:

More from Joseph Bronski:

Great individual geniuses today are simply ignored, cheated or quickly bought out for a song. All the credit today is given to corporate heads like Elon Musk or Bill Gates who've acquired lots of money but have never invented anything. The patent system that once nurtured great individual inventors only protects big corporations. The lone inventor doesn't have the money to take out patents or launch patent infringement lawsuits. In addition, China doesn't respect patents, anything invented in the west will simply be copied by them and made cheaper, to be marketed here. Many brilliant men who once would've had an avenue to market their inventions, are now blocked by the very system that once nourished their creativeness, they simply don't bother inventing any more or if they do, they don't try to market them. Just like music, we now have very little variation in popular music, modern technology has taken the wind out of the sails of creative people. The industry is controlled by large corporations that are afraid of taking the risk of trying something new, hence, popular music has hardly changed in 20 years. We also see very few new gadgets coming out, everything that's advertised to be new are simply rehashed gadgets that were out 40 or 50 years ago. There are companies that look around for expired patents and start making the device or thing that was made profitably in the past. We need to provide a system where the small inventor is protected for 20 or so years so that he can bring his invention to market and make a profit without any worries that a big parasitical corporation or the Chinese will take it away from him.

Very interesting. Another possible angle in the sciences is the enforced specialisation required by both the vast increase in knowledge and the rigid credentialing academy. Former geniuses were able to influence a wide range of subdisciplines within their area, or even engage across multiple disciplines entirely.

As for “poetic genius”, let us simply agree to disagree over whether there are popular lyricists today whose output exceeds the calibre of such classic verses as:

“The Pekes and the Pollicles, everyone knows,

Are proud and implacable passionate foes;

It is always the same, wherever one goes.

And the Pugs and the Poms, although most people say

That they do not like fighting, will often display

Every symptom of wanting to join in the fray.”