Written by Jimmy Alfonso Licon.

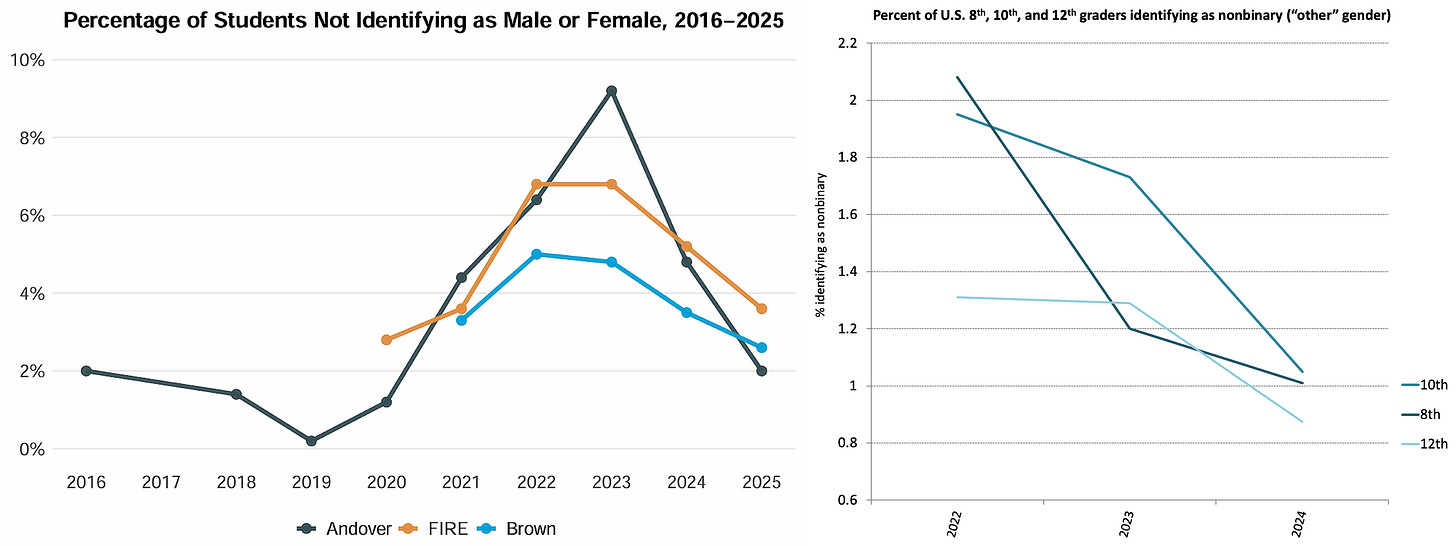

Over the past decade, the number of young Americans identifying as transgender or “non-binary” rose sharply and then declined just as sharply, as Eric Kaufmann and Jean Twenge have recently shown. This pattern invites an obvious political story: transgender identification fell out of fashion due to a cultural backlash and/or its lesser prominence in left-wing politics. But there is another, more subtle explanation for the pattern, namely the dynamics of signalling in a crowded social environment.

Human beings spend a surprising amount of time sending and decoding signals about who we are, what we value and where we stand. Most of these signals entail costs we are willing to bear like time, money, social risk and sometimes even bodily alteration (e.g., foot-binding in China or circumcision in Jewish culture). The central claim of signalling theory — developed independently in economics and evolutionary biology — is that costly signals are more reliable indicators of underlying traits or commitments than cheap ones. This is because cheap signals can be easily faked by those who don’t possess the relevant traits. For example, the peacock grows colorful and elaborate plumage to signal to the peahen that it is capable of surviving despite being encumbered with such a handicap.

When it comes to gender, the same principle applies: declaring an “identity” is a low-cost signal, as compared to, say, undertaking medical transition, changing legal documentation, or living in ways that carry social and professional risks. Individuals who incur those costs send stronger, harder-to-fake signals. Hence when the signalling environment changes — when too many others send weak, easy-to-fake signals — the payoffs shift, and we see a fall in transgender identification, just as Kaufmann describes.

The cost principle

Signalling theory was devised to explain a puzzle: other individuals cannot directly observe our intentions or underlying traits. (We are partially opaque to one another.) They have to infer them from our behavior. For a signal of some trait to be credible under these conditions, it must be easier for genuine carriers of the trait to send than for fakers to do so. Differential costs are what makes this possible.

For example, a university degree is often less about the content of Shakespeare or metaphysics than about demonstrating traits like intelligence, persistence and conformity. And, crucially, getting through a degree is easier for people who do score higher on those traits. The impracticality is part of the signal: if degrees were a walk in the park, they would carry little information.

The same logic applies to social identity. Tattoos, time-consuming activism or medically risky interventions operate as signals. Cheap talk — statements made at low cost and low risk — is less discriminating. When anyone can send a signal just by declaring something, free-riding increases and the information content of the signal declines. This is why many signals (such as fashion trends) follow a pattern of rapid diffusion, saturation and subsequent decline.

Let’s apply this to transgender or “non-binary” identification. A new identity initially functions as a relatively rare and thus informative signal. It differentiates a small number of people from the majority, thereby conveying both underlying traits and alignment with a particular political narrative. As the identity spreads, it becomes cheaper and easier to adopt, if for no other reason than there’s strength in numbers: encouragement from social media, institutions and peers lower the costs of self-identification without raising the costs of insincere adoption.

Once the signal becomes common, its information content declines. Identifying as transgender or “nonbinary” tells observers less about a person’s underlying traits and long-term intentions than when it was rare. At that point, people who seek a strong, credible signal must bear higher costs — such as full-blown medical transition.

Audiences, attention and signal saturation

Circle back to the late 2010s when many Western institutions — schools, media and large companies — offered an attentive and “affirming” audience for gender-related signals. Adopting new gender identities served as a form of personal expression and as a reliable signal of progressive views. As a consequence, the social payoff for low-cost signalling was high. But as signalling became widespread, audiences adjusted. When everyone displays the same badge, it no longer has much purpose. This dynamic explains why a decline in gender signalling can occur without major shifts in partisanship or explicit ideology. What changes is not so much what people believe, but the social payoff from adopting a certain identity.

Unlike verbal identification, a medical or extensive social transition can be seen as a high-cost signal. Surgery and long-term hormone use are, of course, very difficult to reverse, which makes the corresponding signals extremely hard-to-fake. Why would someone incur such costs? There are several reasons, including self-affirmation, higher status in certain political settings, emotional support from others, and an opportunity to signal that one is particularly forward looking, open minded and progressive.

Kaufmann argues that the decline in transgender and “non-binary” identification is not fully explained by changes in mental health or political ideology (although those factors play a role). The pattern appears across red states and blue states, liberal and conservative students, and elite and non-elite institutions. From a signalling-theoretic point of view, this is what we would expect from a shift in the value of a signal rather than in the underlying distribution of underlying traits or intentions. As Kaufmann notes, the change in gender identification “seems to largely be an independent youth fashion that operates on a plane that is separate from politics and mental health”.

When a signal like “non-binary” identification is new, its novelty can create a market itself. As the signal begins to spread, the personal cost of adopting it can go down while the social payoff goes up. This is a recipe for rapid diffusion. After a certain point, however, two things happen. First, the signal no longer sharply distinguishes the “type” it was originally associated with. Second, rival signals emerge that may be cheaper or more effective. As a result, some people abandon the signal, or move on to alternative ways of conveying their traits and commitments.

The observed fall in transgender and “non-binary” identification is not just a cultural or political event; it is also a signalling adjustment. The cheap talkers are moving on.

Jimmy Alfonso Licon is a philosophy professor at Arizona State University, who works on ignorance, ethics, cooperation and God. You can find his Substack here.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

I think signalling is an even better explanation for the vocal transgender "allies". You are (virtue-)signalling you are caring, sympathetic, and part of the "good" group. Very low cost, decent reward in the boom period. Now that the boom is over, the pronouns in bios are disappearing like flies. They’re quickly becoming a signal of naivety, or worse.

So what will be the new signal? Trans-speciesism is too similar to trans-genderism, trans-racialism and trans-ableism failed to gain traction. Even environmental activism is just pissing people off now. As for open-borders; it's only popular as a signal until the migrants show up in the signaler's neighborhood, school, or workplace.