The Myth of The Female Hunter

Debunking a dubious new anthropology paper making the rounds.

Written by Alexander.

A new anthropology paper is making the rounds. It questions an old observation: that men do most of the hunting in hunter-gatherer societies. The paper's title is "The Myth of Man the Hunter: Women's Contribution to the Hunt across Ethnographic Contexts" (Anderson et al., 2023). Here are some headlines in popular media describing it:

"Shattering the myth of men as hunters and women as gatherers." — CNN Science.

"Women have always hunted as much as men." — El Pais.

"The myth that men hunt while women stay at home is entirely wrong." — New Scientist.

"Worldwide survey kills the myth of 'Man the Hunter'." — Science.

"Early Women Were Hunters, Not Just Gatherers, Study Suggests." — Smithsonian Magazine

The headlines get the results wrong in different ways. In the study, researchers identified 391 modern hunting-foraging populations. They found data on hunting in 63 of those. The study relied on existing ethnographic literature, adding no new observations. We can't conclude that this tells us about early human populations since contemporary hunter-forager groups might differ from past groups. Still, many people use modern populations of hunter-gatherers to make assumptions about what past human groups might have been like.

Those are just some minor limitations. They aren't big problems with the paper. The big problems are:

The data do not show it is a "myth" that men are the predominant hunters across these cultures.

The data do not show that women hunt as often as men do.

The data do not show that women have always hunted as much as men.

That men hunt more than women is a robust cross-cultural observation. Further, sex-based roles persist even when both sexes hunt. In cultures reported as having women who are frequent hunters, women are more likely to trap small game with nets than men. The papers cited by Anderson et al. (2023) describe this. The journalists reporting this paper probably won't read them; they won't go through the data file and corroborate the citations. And the average reader certainly won't. They will take home the headline message: the "myth is busted." Women hunt as much as men do. Turns out anthropology was wrong. Turns out evolutionary psychology is a pseudoscience that constantly underestimates women.

Methodology of Anderson et al.

Anderson et al. (2023) examined the existing ethnographic literature for documentation of women hunting. This was categorized as a binary variable. If there was any documentation of women hunting, it was recorded as a 1, a simple "yes." This raises a problem. It does not quantify how much men and women participate in hunting. It didn't matter if hunting was rare for women or if female hunting practices differed significantly from male hunting practices (e.g., trapping birds versus hunting elephants with spears). The paper is not behind a paywall, and the coding file is included, so I recommend that the curious reader look. This is how it was done:

It's important to understand that anthropologists, evolutionary psychologists, and others who study hunter-gatherers have rarely (if ever) claimed: "women never hunt." This paper may be great for debunking the myth that women never hunt, but that is a myth few believed in the first place.

We have long known hunter-gatherer women hunt. However, in some societies, it is rare. In others, it is more common. In very few cultures, women hunt as much as men do. When women do hunt, it is often not what men hunt. The "myth" of man the hunter arose because, consistently across cultures, anthropologists observed segregation of sexes whereby men participated in hunting substantially more and differently from women.

By coding "women hunt" as a binary, Anderson et al. (2023) grouped cultures where female hunting is rare with cultures where it is more common. They did not quantify the percentage of women participating in hunting nor the time spent hunting. They did quantify some differences in the type of hunting, for example, women hunting small game and men hunting large game. However, they also omitted other sex differences in hunting roles.

Methodology of the current analysis

In this analysis, I will use the same papers that Anderson et al. (2023) used. Instead of asking, "has a woman ever hunted," I will examine sex differences in hunting roles.

Anderson et al. (2023) did not include page references in their coding document, so I had to dig through these to find the appropriate references. I have included passages from the authors in the ethnographies cited to justify my analysis. Where information is vague or incomplete, I have included additional sources. Here I will look at two things:

Do we see any sex differences in hunting roles?

How large are those sex differences, or how much do they segregate men and women?

In the subsequent section, I will share passages from the ethnographies cited by Anderson et al. (2023). There are 63 different cultures; they won't all fit, so I will include only the African cultures listed.

What the ethnographers say about sex differences in hunting

The !Kung San

"The division of labor by sex is virtually universal. Men hunt and gather; women primarily gather and very occasionally hunt; both sexes fish and gather shellfish. The actual productive process may be individual or cooperative. Men may hunt singly or in groups; women may gather alone or with others." (Lee, 1979).

The Ju/' hoansi

"First, there exist foraging societies such as those of the Ju/' hoansi in which women are categorically prohibited from all hunting. Second, and more commonly, there exists a proscription of women's use of hunting weapons, a rule which variously has the effect of eliminating or of marginalizing women's labor in hunting big game. Women's hunting labor, as a result, when and where it exists, is always ancillary to that of men and almost everywhere qualitatively distinct from it." (Brightman, 1996).

The Baka

"Although subsistence hunting is cross-culturally an activity led and practiced mostly by men, a rich body of literature shows that in many small-scale societies women also engage in hunting in varied and often inconspicuous ways … Hunting was more frequent among the Baka: 59.4% (n = 49) of Baka women had led at least one hunting trip, 6.0% (n = 5) had assisted in hunting trips, and only 34.9% (n = 29) had not participated in hunting during the sampled days. All Baka men fell within our category of hunter." (Reyes-Garcia, 2020).

The Aka

For the Aka and following groups, Anderson et al. (2023) relied on papers about net hunting.

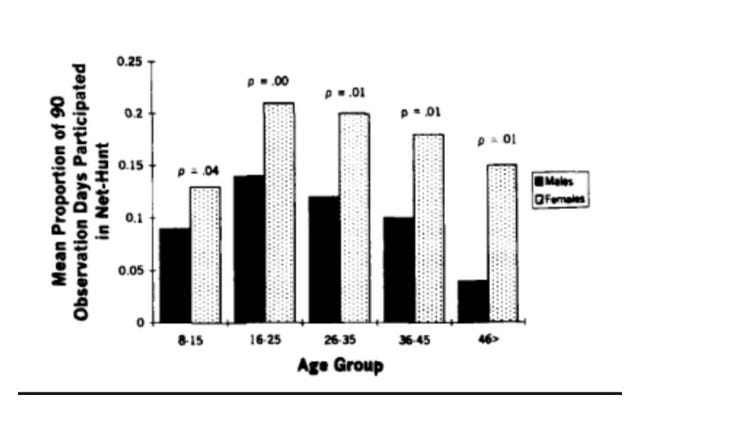

"Overall, women were much more likely to net-hunt than men were. Only 4 of 126 females (3 percent) in Mossapoula did not net-hunt during the entire observation period, compared with 12 of 116 males (10 percent) who never hunted (chi-square = 5.17, p < .05)" (Noss & Hewlett, 2001).

Women and children did hunt with nets more:

However, the Aka also hunt game with spears. According to Lew-Levy et al. (2021) and Kitanishi (1995), all adult and adolescent men participate in spear hunting. Women do not. A division of hunting roles by sex exists. It is stereotypical of what you might expect. Women and children place nets to capture birds. Men use spears to hunt big game.

The Bambote

"Net hunting (lubala) is a group activity, in which both men and women participate … after selecting a place, men set up the nets, which are usually arranged in a slight arc to block any escape. The nets cover one third of the circumference of the hunting ground at most, and the rest is covered by women spacing themselves some 50 m apart. When women are ready at their positions, they start driving animals. Women intermittently shout "hooow, hooow" or "heeei, heeei" thus alerting the animals in the thickets to the presence of humans in a" particular direction ; this is called kusamina. Most men silently wait for game in front of their nets, but a few enter the thickets to search for hiding animals, throw stones into the thickets, or set fire to the grasses to drive out the animals. Driving out is called kuswcrga. Meanwhile, when a man finds an animal, he signals the women by whistling, and the women begin a loud uproar. Thus startled, the animal files from the noise and rushes into the nets. The man nearest the animal pounces on it and kills it with blows." (Terashima, 1980).

In the Bambote, men and women both participate in net hunting. However, we do see a segregation of hunting roles by sex. Women flush animals. Men capture and kill animals. Why is this different from the Aka? It may be because the Bambote capture large game in nets, such as reedbucks and bushbucks. The Aka primarily capture birds. For the Bambote, men are assigned to subduing and killing large animals. Further, Terashima (1980) describes bow and persistence hunting for large game: men do this, but no description is made of women doing this.

The Efe Pygmies

"The association of burden carrying with women's work is so strong that when men kill a very large animal, they will travel considerable distances back to camp in order to fetch women to carry the meat, rather than carrying it back themselves" (Brightman, 1996). Bailey & Aunger (1990) similarly describe, "men hunt alone, but most meat is procured and most hunting time is spent in male groups consisting of 4-22 men."

The Mbuti

"Consider, for example, Mbuti women who are "likely to be off on the hunt, or on the trail somewhere when birth takes place" (Brightman, 1996).

Not much to go on, but this gives us "women hunt." Ichikawa (2021), however, describes elephant hunting in the Mbuti as being done by men; "a mtuma [experienced elephant hunter] is often accompanied by one or two young men, his younger brother, son or nephew, as apprentice or assistant doing daily chores."

Further, rituals described in Ichikawa (2021) preceding and following an elephant hunt are divided by sex.

The Mbuti are a pygmy group like the Baka, Aka, Bambote, and Efe. Ichikawa (2021) describes women participating in net hunting here as well, but not in hunting large game or with groups of men. In the code given by Anderson et al. (2023), hunting with men is given a 1 for "yes," and "3," indicating hunting of large game, but I don't see this occurring in Brightman (1996). Large game hunting by women is also not described in the recent literature by Ichikawa (2021).

The Sua (Tswa)

Anderson et al. (2023) include the Sua in their data, but the reference is empty. I expected this to indicate that it was in the previous reference (Brightman), but Brightman (1996) does not mention the Sua or Tswa that I can see.

Given this, we'll have to look elsewhere for information about the Sua. According to Bailey and Aunger (1989) the Sua or Tswa are one of four pygmy groups within the BaMbuti, alongside the Efe, Aka, and Mbuti. Bailey and Aunger describe the hunting behavior similarly, with a division of hunting by sex: "a very important difference with respect to the labor that goes into net hunting vs. archery is that, among archers, hunts are almost exclusively conducted by men (for exceptions see Terashima, 1983), whereas, among net hunters, women routinely participate in hunts; they act as beaters to drive the game into the nets."

The Kikuyu

The Kikuyu are the next entry in the Anderson et al. (2023) data and similarly have no citation, so again, I don't know where they derived their coding from. We can once more look elsewhere for information about the Kikuyu. I can't find much about traditional hunting, perhaps partly because the Kikuyu have largely modernized. However, Mulligan & Gibson have this to say on Kikuyu gender roles: "Traditionally, the division of labor between males and females was rigidly defined. Each gender had its own responsibilities. Custom prescribes the line between a man's work and a woman's work and this begins in the earliest years."

The Hadza

"The Hadza have a sexual division of labor; men mostly hunt game and collect honey, and women acquire plant goods, including tubers and berries." (Marlowe, 2010). The Hadza are a relatively well-studied population, and it is well-documented that they have a fairly strict division of hunting and foraging labor (Berbesque & Marlowe, 2009; Froehle, 2019; Lew-Levy et al, 2021).

The BaKola

The BaKola are another pygmy group. Ngima (2006) describes men and women manufacturing all the weapons, women carrying the spears of male hunters, and net hunting. Again, women take the role of flushing out game to be captured in the nets. Additionally, Ngima describes fishing as female-dominated.

Ngima also notes that more egalitarian roles, for example, those of the BaKola, are the exception: "Most African societies have a division of labor and social roles between men and women. Men are assigned hard duties like clearing the bush, felling down trees, constructing houses, hunting, maintaining cocoa and/or coffee plantations … However, the Bakola have maintained their own ways and customs to organize the works, despite the frequent contacts with their Bantu neighbors. They have no prejudice about the division of labor in their society; women's participation is actually as important as men's in net hunting, honey collecting, fishing and farming."

The Bofi

Two passages from Lupo & Schmit (2002) describe the sexual division of hunting labor:

"The most common communal technique is the net-hunt. Net-hunts are well described in the literature (see Harako, 1976; Putnam, 1948; Schebesta, 1936; Tanno, 1976; Turnbull, 1965), and only the salient features are mentioned here. Among the Bofi, net-hunts can involve groups of up to 35 people and can include men, women, and children. Infants who are usually carried by their mothers often accompany the task group, and small children old enough to keep up with the adults often assist in the hunt. Nets are set end to end to form an arc in the forest, and beaters drive prey into the nets where they are dispatched."

"Hunting with crossbows and poisoned arrows is usually a solitary technique conducted by men. Hand capture involves several techniques some of which are tool-assisted. Slow moving and docile animals, such as tortoises, young birds, and pangolins, are grabbed when encountered. Giant pouched rats are removed from subterranean burrows through excavation by hand or with a metal hoe. Wooden probes made from saplings are often used to help extract animals from burrows. Dogs and fire may also be used to flush prey from heavy vegetation or subterranean burrows."

Again we see a reference to communal net-hunting and a division by sex for individual hunting.

Analysis

Based on the description of the cultures in Anderson et al. (2023) and the research cited above, I coded cultures according to the following:

A clear sexual division of hunting labor: a binary yes/no.

The extent to which hunting was segregated overall: a scale of 1-4. A 1 indicates no segregation; men and women perform the same hunting tasks in mixed groups. A 4 indicates nearly total segregation.

Here are the results for the African societies used:

100% of the societies had a sexual division of labor in hunting. Women may have participated with men in some hunting contexts, typically capturing small game with nets, but participated much less in large game hunting with weapons or by persistence. Even within these contexts, it was usually the case that the role of women during the communal hunt was different. For example, women flushed wild game into nets while men dispatched the game.

These are my subjective ratings based on the papers I read in Anderson et al. (2023) and the supporting literature I cited. You may disagree and assign some different ratings. The point is that there is substantial variation across cultures in sex-based hunting roles. Additionally, none of the societies truly have an absence of these roles.

Discussion

Why did the perception of "man the hunter" arise? It's likely because we see many sex-segregated hunting practices, particularly in hunting large game with weapons. Additionally, when you think of hunting, the first thing that comes to mind may not be chasing birds into nets. You probably think of a man with a spear — usually a man, not a woman, with a spear.

Nonetheless, it's important not to devalue the role of small game hunting and foraging. Ichikawa (2021) noted that small game net hunting produced an equal supply of food in tonnes but was also stable and not sporadic compared with hunting elephants. In agricultural societies, women are not merely sitting at home either. Farming labor is shared and women tend to produce as much food as men. Women work hard across cultures. They are not merely sitting in the cave waiting for you to return the mammoth meat.

For some people, that is not good enough. They are driven by a belief that the egalitarianism of hunter-gatherer societies means they have no sex-based roles or divisions. This is not only a belief but an ideological desire. They want to believe that hunter-gatherer egalitarianism means the sameness of the sexes. On that, I will leave you with what Lewis (2014) wrote about gender roles for one pygmy hunter-gatherer group related to those reviewed in this literature:

Mbendjele recognize, cultivate, and celebrate gender differences, but value them equally. To understand egalitarian societies, it is necessary to understand that individual variation and equality coexist, so to understand gender egalitarian societies, it is necessary to recognize that gender difference and equality coexist

[…] Mbendjele men and women spend most of their waking time apart; in the forest women gather and fish together with other women and children, men go looking for honey or hunting in smaller male‐only groups.

Alexander is a grad student in behavioral and cognitive research. His research interests are in relationships and attraction. You can follow him on Twitter for interesting research threads and YouTube for evidence-based dating tips.

Read more of Alexander’s work:

Egalitarians are incapable of arguing against the obvious statistical facts that eviscerate their worldview, so their only last resort is the NAXALT argument; not all X are like that! Deboonked! There is evidence of 1 woman involved in a mammoth hunt in human history, some women fishing and hunting small animals, therefore egalitarians are right about everything!

I enjoyed your analysis of the published papers. Too often journalists seem to take for granted that a peer-review in an academic journal is de facto axiomatic. However, it's all very strange that anyone would presume that there were never any female hunters. We have a constellation named after Artimes - goddess of the hunt - after all.