The Great Cognitive Advance

On a per capita basis, the highly intelligent became ten times more numerous in England between 1000 and 1850.

Written by Peter Frost.

DNA from human remains is showing us how different populations have evolved over time, not only during prehistory but also well into recorded history. This evolution has affected a wide range of mental and behavioral traits: cognitive ability, time preference, propensity for violence, monotony avoidance, rule following and empathy, among others.

Such traits vary among human populations because different cultures have imposed different demands on mind and body. In general, a culture will favour those who can better exploit its possibilities, just as the natural environment does. There has thus been a process of coevolution: we make culture, and it remakes us—by selecting those among us who survive and pass on their genes. This coevolution has followed different trajectories in different times and places.

One trajectory began during the Early Middle Ages on the northwestern fringe of Europe, where fishing peoples were learning how to use the North Sea for long-distance trade. From such inauspicious beginnings, they would become globally dominant in a little over a thousand years:

In every respect, the 7th century marked a turning point: the old economic system was in its terminal phase and a new world was beginning to emerge. The accelerated decline of Mediterranean trade in the 7th century was linked by Belgian historian Henri Pirenne (1862-1935) to the Arab invasion; we have seen that the decline goes further back in time, even though Arab expansion in the 7th-8th centuries and Saracen piracy undoubtedly helped reduce trade even more …

But the great change was really the emergence of the North Sea as the main space of international trade with, around the mid-7th century, the birth of a network linking Frisia, England, Scandinavia and the Frankish world. (Chandelier, 2021, p. 192)

The failure of the Roman economy

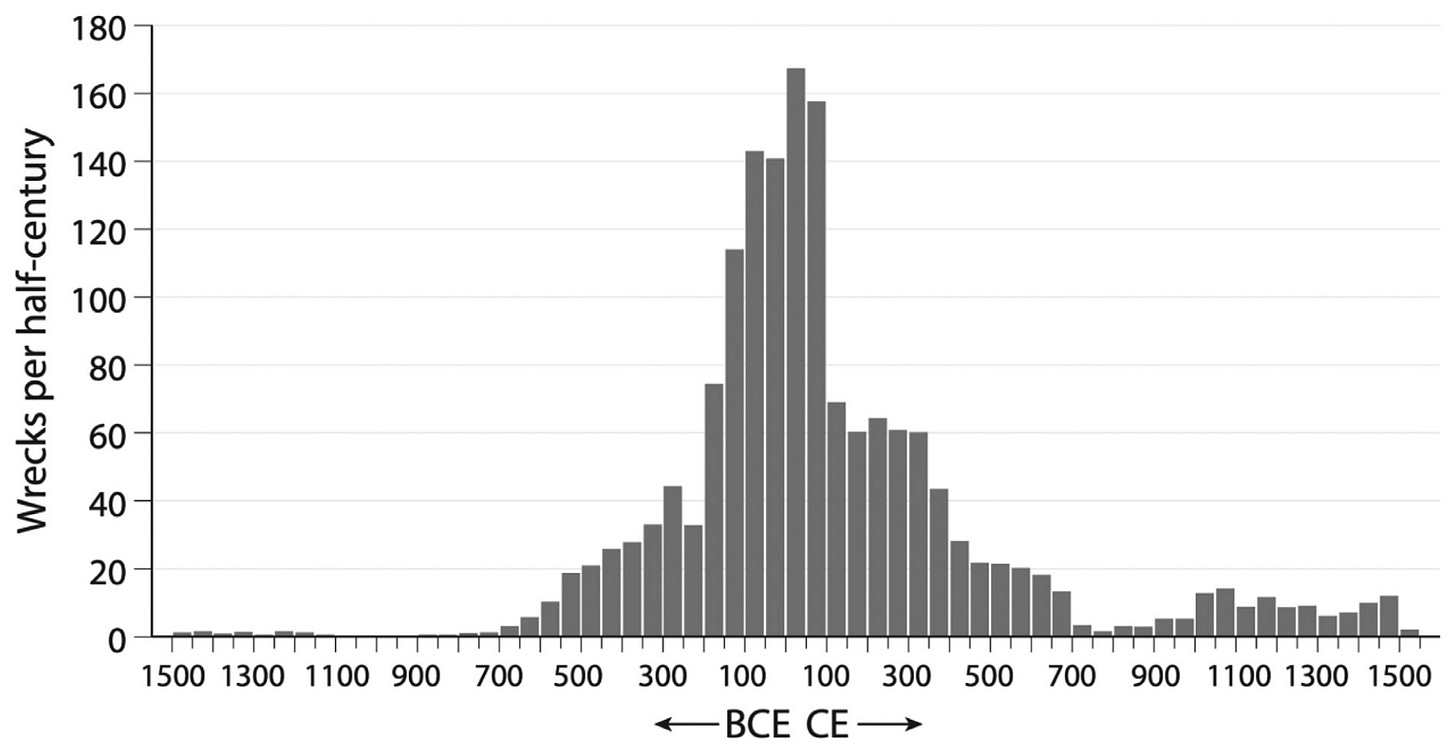

Why did the North Sea overtake the Mediterranean in international trade? Certainly, the latter region was adversely affected by the Arab conquests of the Middle East and North Africa. But the economic decline began much earlier. Shipwrecks on the bottom of the Mediterranean have been dated overwhelmingly to the time between the first century BC and the first century AD. Silver mining in Spain and Cyprus likewise fell sharply after the first century AD, as shown by lead contamination of Greenland’s ice sheet (Terpstra, 2019).

This decline occurred not only before the Arab conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries, but also before the barbarian invasions of the fourth and fifth and the Imperial Crisis of the third. And it seems inconsistent with modern economic thinking: bigger markets should create economies of scale, as well as a better match between supply and demand. So what caused things to go wrong?

Familialism, cronyism and nepotism. One cause was the low level of social trust. People trusted only their close friends and relatives, keeping everyone else at arm’s length. As a result, economic activity was bottled up within family networks, the major exception being physical marketplaces where buyer and seller could meet face to face. Because the market principle remained trapped within small pockets of space and time, it could not generalize to all transactions in Roman society. An economy of markets never evolved into a true market economy.

Thus, when the Pax Romana was imposed in the first century BC, a large space opened up for the peaceful exchange of goods and services. Economic activity surged but remained largely within the much smaller high-trust environments of family businesses. Once that source of economic activity had been tapped out, there remained little scope for further growth.

Deterioration of physical health. Familialism, cronyism and nepotism may explain why the Roman economy grew only to a certain point. But the ensuing decline had at least two other causes.

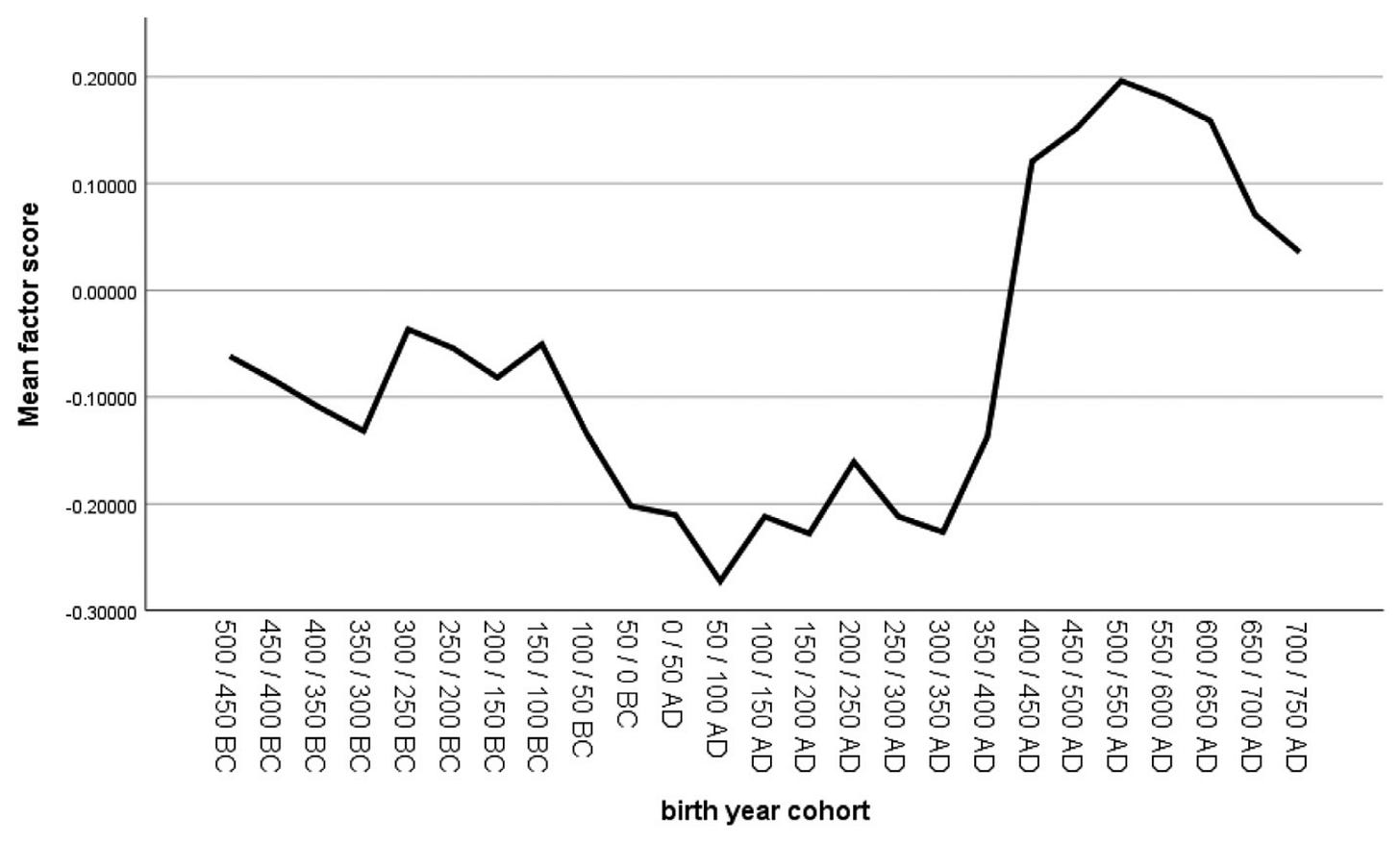

One was a deterioration of physical health, as indicated by the length of long bones belonging to over 10,000 adult men and women born between 500 BC and 750 AD. The data show a steady decrease from the second century BC, reaching a low point in the second half of the first century AD, followed by a slow recovery and then a dramatic recovery from the fifth century AD (Jongman et al., 2019).

This trend may seem paradoxical, as it inversely correlates with the success of Imperial Rome: physical health deteriorated as the Empire expanded and then recovered as the Empire shrank. The study’s authors concluded that the Romans created not only an integrated Mediterranean economy but also “the first integrated disease regime”.

In health terms, however, the consequences were not necessarily that favourable. Roman cities had become the focal point of viruses and bacteria that all vectored in on them, to find a densely packed population. Historically, a declining biological standard of living under conditions of economic development and increasing economic integration is not unique, of course. (Jongman et al., 2019)

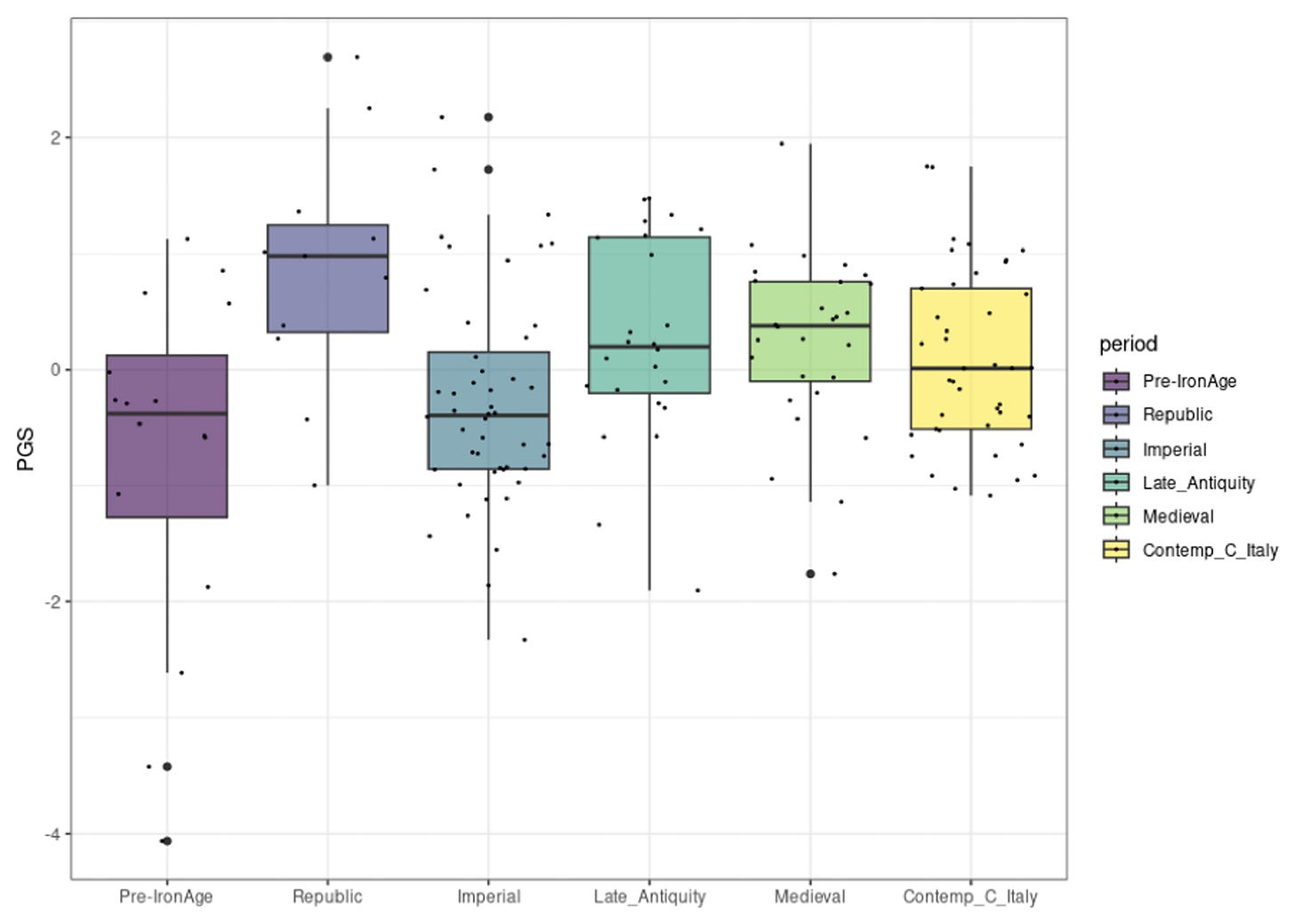

Cognitive decline. The other cause was a decrease in average cognitive ability. Fewer people could master the skills of numeracy, literacy and budgeting that are so essential to economic activity.

This decline was driven by an uncoupling of reproductive success from economic success—as I argued in a previous article. The wealthy were no longer using their wealth to bring children into the world. A rich man might prefer to leave his wife for a younger woman of low social status, often adopting her children. Or he might never marry. The resulting fall in cognitive ability can be seen in DNA retrieved from the human remains of that period (Frost, 2024b; Piffer et al., 2023).

As average cognitive ability decreased, so did its manifestations in daily life. The Romans still excelled at directing large numbers of people, often slaves. But they were not so good at innovation. Their medieval successors took much less time to find better ways of doing things:

Unseen in Roman society were the humble wheelbarrow and stirrup, which would not appear until the Middle Ages. Apart from mechanical clocks, medieval Europe invented heavy ploughs, spectacles, windmills, iron-casting, firearms and paper. The first half of the fifteenth century would add the printing press. Well before that time, medieval texts had been published in codex form, a massive improvement on the unwieldly book scroll of Roman antiquity. Along with better carriers of written information, the Middle Ages adopted a consistent system of graphic symbols, greatly facilitating the readability of the Latin script. Improved ship design in the thirteenth century allowed Mediterranean sailing year-round, unlike in Roman times when travel largely ceased during the winter months. … [T]he maritime shippers of the Middle Ages rejected heavy, breakable ceramic vessels as transport containers. Instead, they adopted the more practical wooden barrel, which had “a better volume to weight ratio, more efficient stacking capability, and greater maneuverability.” (Terpstra, 2019)

The success of medieval and post-medieval Europe

In the seventh century, a new space for trade opened up around the North Sea (Melleno, 2014). Here, local traders had a knack for exploiting opportunities across a potentially large area, unlike other trading peoples for whom markets were merely physical marketplaces—small islands of exchange beyond which people produced for family, kin or lord. The North Sea traders were the first to break free from an economic model where the individual is embedded in static, long-lasting relationships based on rank, kinship and locality.

In this, they had a behavioral advantage. The North Sea and the Baltic form the core zone of certain tendencies that, for at least a millennium, have prevailed north and west of a line running from Trieste to St. Petersburg, i.e., the “Hajnal line.” These are tendencies toward individualism, the nuclear family, late marriage and solitary living, as well as a greater willingness to trust strangers and form bonds of impersonal prosociality (Frost, 2025).

Such tendencies didn’t come into being with the market economy—they arose long before for an unrelated reason. But they did provide the best behavioral conditions for a market economy once the possibility of creating one emerged. Northwest Europeans were thus well-positioned to organize economic relationships on a much larger scale (Frost, 2020). Meanwhile, with the consolidation of state power in Western Europe from the 11th century onward, and the consequent rise of the rule of law, a consensus emerged on the need to execute violent males so that law-abiding people could live in peace. By the Late Middle Ages, courts were condemning to death between 0.5 and 1% of all men in each generation, with perhaps just as many dying at the scene of the crime or in prison while awaiting trial. The pool of violent men dried up until most murders occurred under conditions of jealousy, intoxication or extreme stress. As a result, the homicide rate fell from 20–40 homicides per 100,000 in the Late Middle Ages to 0.5–1 per 100,000 in the mid-20th century (Frost & Harpending, 2015).

People could now get ahead through trade and work, rather than through theft and plunder. This new, pacified environment favored the growth of the market economy and the success of those who possessed the necessary skills, especially literacy, numeracy and budgeting. They would become the middle class.

The great cognitive advance (11th to 19th centuries)

In England, from the eleventh century onward, the middle class outperformed the lower classes in having children who survived to adulthood. This class therefore grew as a proportion of the population, gradually replacing the lower classes through downward mobility. Gregory Clark has argued that the medieval/post-medieval period saw English society become increasingly middle class, mentally and behaviorally. "Thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work were becoming values for communities that previously had been spendthrift, impulsive, violent, and leisure loving” (Clark, 2007; Clark, 2009; Clark, 2023; Frost, 2022c).

Georg Oesterdiekhoff has argued for a similar evolution across Western Europe as a whole. He views this evolution in terms of Jean Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, i.e., more and more people could go beyond preoperational thinking (egocentrism, anthropomorphism, animism) and achieve operational thinking (ability to understand probability, cause and effect and another person’s perspective) (Oesterdiekhoff, 2023; Rindermann, 2018, pp. 49, 86-87).

With the retrieval of DNA from human remains, we can now verify this model of recent Western European evolution by comparing genomes from different time periods. Two such studies have been done recently.

In the first study, present-day genomes were compared with genomes from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages (n = 467). The comparison showed a substantial rise in mean cognitive ability over time—between one third and one half of a standard deviation (Frost, 2024a; Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024).

The actual rise may have been even larger, since it is imperfectly measured by a comparison between medieval and present-day genomes. At one end of the timeline, according to Gregory Clark, cognitive ability had already begun to rise during the Middle Ages. At the other, it may have peaked in the Victorian Era and then declined thereafter (Frost, 2022d). Also, the rise in cognitive ability may have begun earlier in some regions than in others.

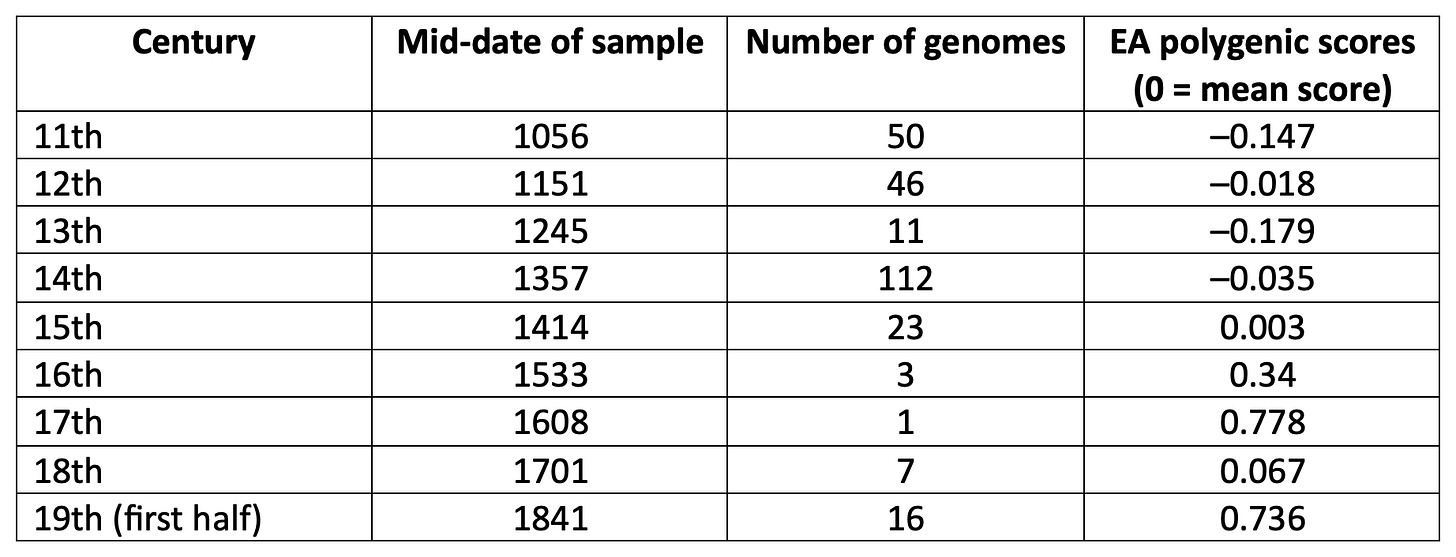

To address these limitations, a second study was conducted with genomes from only one region of England (Cambridge and surrounding area, n = 269). The genomes are from the eleventh to nineteenth centuries (Piffer & Connor, 2025).

For some of these centuries, notably the sixteenth to eighteenth, we have too few genomes for a century-by-century analysis. Nonetheless, the overall trend is clear: a rapid increase in mean cognitive ability from the 1300s onward.

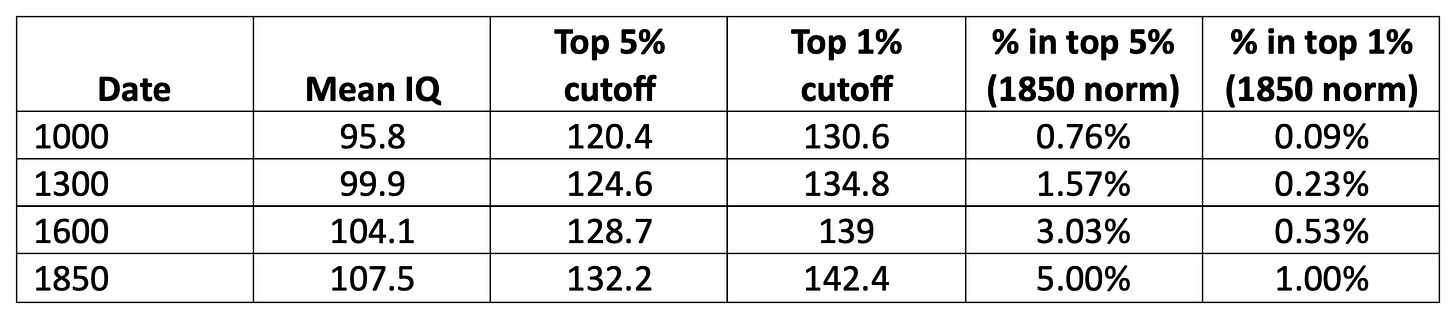

Particularly impressive is the increase in the "smart fraction": the top 1% in 1850 was as smart as the top 0.1% in the year 1000. In the following table, EA scores have been converted into IQ scores for ease of interpretation.

Thus, on a per capita basis, the last millennium saw a massive increase in the number and proportion of highly intelligent people. Intellectuals were no longer voices crying in the wilderness. They could now meet and socialize in coffeehouses, learned societies and debating clubs. This synergy would give rise to the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, ultimately energizing all areas of life—not only the sciences but also literature, music and the arts (de Courson et al., 2023).

The authors of the above studies—Davide Piffer, Gregory Connor and Emil Kirkegaard—intend to pursue this avenue of research further. In particular, they hope to answer the following questions:

Did this cognitive evolution proceed at the same pace from the eleventh to nineteenth centuries? The current data suggest that it was sluggish at first and then took off sometime in the 1300s.

Did the take-off occur initially in one part of Western Europe and then spread elsewhere? One candidate region would be England and Holland, which began their economic take-off in the 1300s (Frost, 2022a). Another would be northern Italy during the Renaissance (Rindermann, 2018, p. 133, 141-142, 259-260).

When did this cognitive evolution come to a halt? Did it peak in the late nineteenth century and decline thereafter, with the rise of industrial capitalism and the severance of the link between economic and reproductive success? (Frost, 2022d).

Was there a parallel evolution with other mental and behavioral traits? For example: time preference, propensity for violence, impulse control, empathy etc.

Did this cognitive evolution include certain alleles that are cognitively beneficial as heterozygotes but deleterious as homozygotes? One example might be alleles for autism, which became more frequent with the rise in cognitive ability (Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024). This sort of heterozygote advantage has already been noted in Ashkenazi Jews with respect to lysosomal storage diseases: Tay-Sachs; Gaucher's; Niemann-Pick; and Mucolipidosis Type IV. All of these alleles became frequent over the same short span of time, in the same population and in the same metabolic pathway—an indication of natural selection, and strong selection at that (Cochran et al., 2006; Diamond, 1994; Frost, 2022b).

To answer these questions with sufficient detail and clarity, we will need more genomic data from medieval/post-medieval times. Such data could also help us better understand the recent evolution of other genetically influenced traits.

Peter Frost has a PhD in anthropology from Université Laval. His main research interest is the role of sexual selection in shaping highly visible human traits. Find his newsletter here.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

References

Chandelier, J. (2021). L’Occident médiéval. D’Alaric à Léonard. 400-1450. Mondes anciens, Paris: Belin. https://www.belin-editeur.com/loccident-medieval

Clark, G. (2007). A Farewell to Alms. A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton University Press: Princeton. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691141282/a-farewell-to-alms

Clark, G. (2009). The domestication of man: the social implications of Darwin. ArtefaCToS, 2, 64-80. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277275046_The_Domestication_of_Man_The_Social_Implications_of_Darwin

Clark, G. (2023). The inheritance of social status: England, 1600 to 2022. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A., 120(27), e2300926120 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2300926120

Cochran, G., Hardy, J., & Harpending, H. (2006). Natural history of Ashkenazi intelligence. Journal of Biosocial Science, 38(5), 659-693. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932005027069

de Courson, B., Thouzeau, V., & Baumard, N. (2023). Quantifying the scientific revolution. Evolutionary Human Sciences, 5, E19. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2023.6

Diamond, J.M. (1994). Jewish Lysosomes. Nature, 368, 291-292. https://doi.org/10.1038/368291a0

Frost, P. (2010). The Roman State and genetic pacification. Evolutionary Psychology, 8(3), 376-389. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491000800306

Frost, P. (2020). The large society problem in Northwest Europe and East Asia. Advances in Anthropology, 10(3), 214-134. https://doi.org/10.4236/aa.2020.103012

Frost, P. (2022a). When did Europe pull ahead? And why? Peter Frost’s Newsletter. November 21.

Frost, P. (2022b). Ashkenazi Jews and recent cognitive evolution. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 5.

Frost, P. (2022c). Europeans and recent cognitive evolution. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 12.

Frost, P. (2022d). The Great Decline. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 20.

Frost, P. (2024a). Cognitive evolution in Europe: Two new studies. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, March 14.

Frost, P. (2024b). How Christianity rebooted cognitive evolution. Aporia Magazine, October 10.

Frost, P. (2025). Adapting to an environment of their making. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, February 25.

Frost P., & Harpending, H. (2015). Western Europe, state formation, and genetic pacification. Evolutionary Psychology, 13(1), 230-243. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491501300114

Jongman, W. M., Jacobs, J.P. & Goldewijk, G.M.K. (2019). Health and wealth in the Roman Empire. Economics & Human Biology, 34, 138-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.01.005

Melleno, D. (2014). North Sea networks: trade and communication from the seventh to the tenth century. Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 45, 65-89. https://doi.org/10.1353/cjm.2014.0055

Oesterdiekhoff, G.W. (2012). Was pre-modern man a child? The quintessence of the psychometric and developmental approaches. Intelligence, 40, 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2012.05.005

Piffer, D., & Connor, G. (2025). Genomic Evidence for Clark's Theory of the British Industrial Revolution, preprint, ResearchGate, June. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392808200_Genomic_Evidence_for_Clark's_Theory_of_the_British_Industrial_Revolution

Piffer D, Dutton, E., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2023). Intelligence Trends in Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of Roman Polygenic Scores. OpenPsych. Published online July 21, 2023. https://doi.org/10.26775/OP.2023.07.21

Piffer, D., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2024). Evolutionary Trends of Polygenic Scores in European Populations from the Paleolithic to Modern Times. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 27(1), 30-49. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2024.8

Rindermann, H. (2018). Cognitive Capitalism. Human Capital and the Wellbeing of Nations, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cognitive-capitalism/7C10B724756D97F00B7AF0515B800CC5

Terpstra, T. (2020). Roman technological progress in comparative context: The Roman Empire, Medieval Europe and Imperial China. Explorations in Economic History, 75, 101300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2019.101300

As usual, engaging and informative.