Science and Meaning

Science does not care about meaning, but that does not mean the world is meaningless.

Written by Bo Winegard.

Recently, a deflating remark about science and meaning by Yuval Noah Harari made the rounds on Twitter:

From a purely scientific viewpoint, human life has absolutely no meaning. Humans are the outcome of blind evolutionary processes that operate without goal or purpose. Our actions are not part of some divine cosmic plan, and if planet Earth were to blow up tomorrow morning, the universe would probably keep going about its business as usual. As far as we can tell at this point, human subjectivity would not be missed. Hence any meaning that people ascribe to their lives is just a delusion.

The claim, common in one form or another, is that science is the final arbiter of what is really real. If something cannot be detected, measured or affirmed by the scientific method, it does not truly exist. Meaning, because it is not “scientifically objective,” is dismissed as an illusion. The universe, on this view, is cold, impersonal and fundamentally indifferent. And the man who believes that raising his daughter or writing a great novel gives his life meaning is not just wrong, he is deluded.

Yet this conclusion rests on a category mistake, one that is essential to correct because science enjoys extraordinary prestige in our civilization. Indeed, for many contemporary intellectuals, science has come to function not merely as a method of inquiry, but as a comprehensive worldview — a grand narrative that promises to replace the allure of metaphysics with the plain but practical charm of empirical knowledge. In this vision of scientific triumph, there is the world before science and after science, before enlightenment and after enlightenment. And our pre-Galilean ancestors, our Platos and Augustines, our Aristotles and Luthers, who wrestled with the great puzzles of life were still in the larval stage of thought, their answers little more than ignorant gestures in the dark.

For example, here is Dawkins in the introduction of The Selfish Gene:

Why are people? … Darwin made it possible for us to give a sensible answer to the curious child whose question heads this chapter. We no longer have to resort to superstition when faced with the deep problems: Is there a meaning to life? What are we for? What is man?

This whiggish vision of science is not wrong because science is uninspiring or unproductive; it is wrong because science is a method of inquiry that is astonishingly effective but only within a narrow domain of human activity. Science does not replace metaphysics or meaning and it does not arise in a vacuum.

Rather it emerges from a world that is already meaningful. Before humans engage in science, or even philosophical reflection, they encounter a world that is full of significance, full of threats and opportunities, of purposes and failures, of tragedies and triumphs. Long before the scientist measures, the human being cares. Science does not create our meaningful engagement with reality. It presupposes it. And it no more replaces meaning than a musical score replaces the sadness and beauty of a Tchaikovsky symphony.

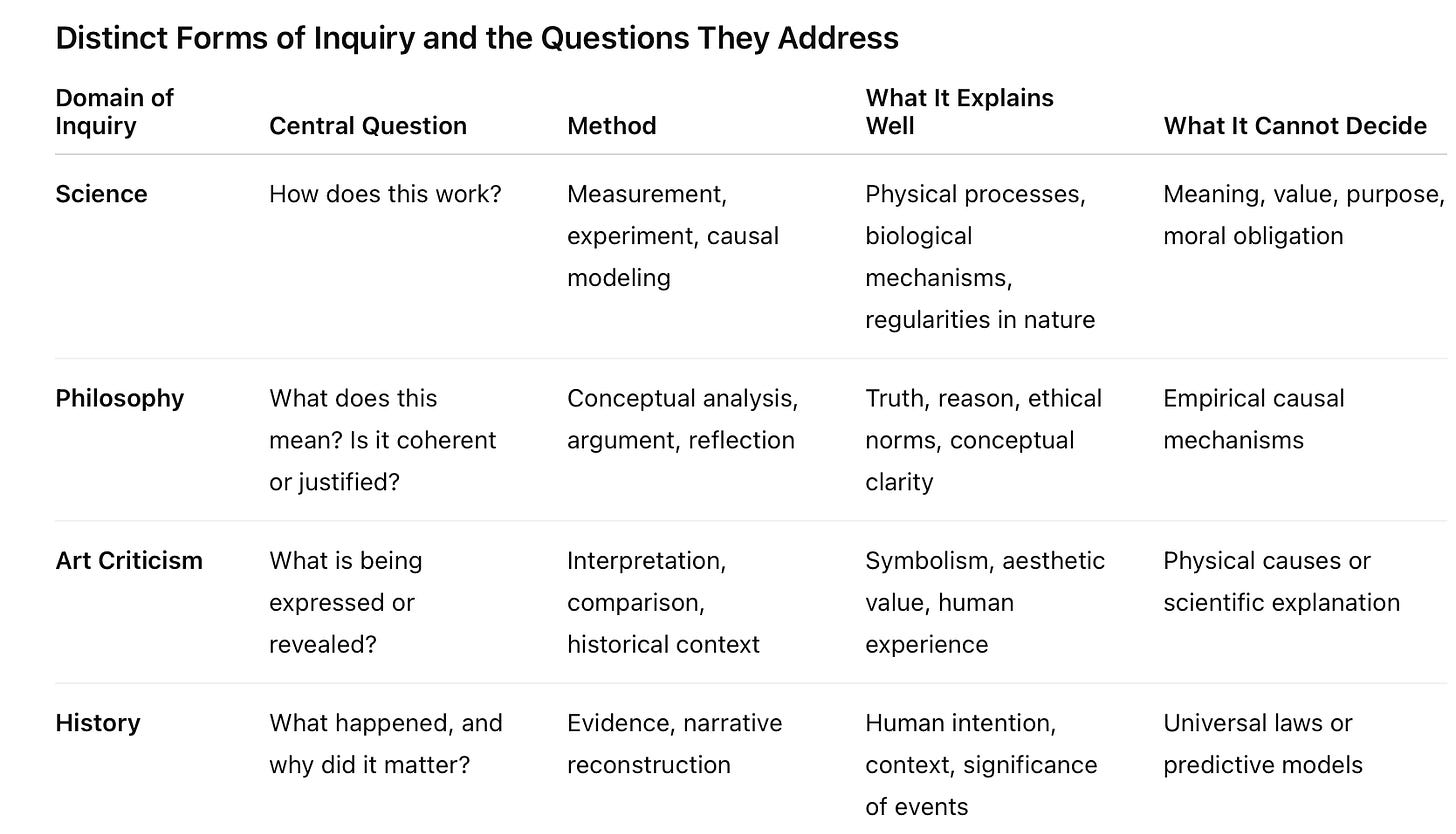

What is more, science is extraordinarily effective precisely because it sets aside questions of meaning, value and purpose in order to focus on causal processes. It asks how things work, not what they mean; how events follow one another, not why they matter. The category mistake is to confuse this methodological restraint with a discovery about reality itself, to conclude that because science necessarily brackets meaning, the universe must therefore be meaningless.

Dawkins seems to expect science to provide an objective, non-superstitious answer to the question “What is the meaning of life?” But that is like expecting a thermometer to tell us what it is like to be cold. A thermometer can tell us the temperature with remarkable precision; Jack London’s To Build a Fire tells us what it means to be chilled to the bone.

One often encounters a particularly deflating form of this scientism in popular works by neuroscientists and biologists who appear to take delight in a posture of provocative nihilism. For example, here’s Robert Sapolsky from Determined:

Maybe you’re deflated by the realization that part of your success in life is due to the fact that your face has appealing features. Or that your praiseworthy self-discipline has much to do with how your cortex was constructed when you were a fetus. That someone loves you because of, say, how their oxytocin receptors work. That you and the other machines don’t have meaning.

The idea, as best as I can tell, is that love, hope, meaning, morality are all products of brain cells and chemicals and therefore not actually real. We are “machines” programmed by nature to reproduce, care for our children, and die. The rest, the material that makes up our great literature, our great films and our great religions, is the fantasy we spin for ourselves lest we perish from the bleak truth of our meaningless existence.

One sees the same category mistake. Neurons may be necessary for love, but they are not identical with love. Love is a complex psychological, social and cultural phenomenon—an experience, an emotion and a process in a broader narrative of meaning and moral obligation. It should be no more disconcerting to learn that someone loves partly because of sustained patterns of neural activity than it is to learn that Aaron Judge hit a home run partly because the exit velocity of the ball off his bat was 108 miles per hour. The neuroscientist and the physicist can illuminate the causal processes involved in love and home runs, but they cannot tell us what either means or why either matters.

The error that gives rise to Harari’s arguments, and to much of modern scientism, is thus not scientific but philosophical. Science is a marvelous human invention and an unparalleled engine for the accumulation of empirical knowledge. But the universe does not become meaningless simply because science cannot discover meaning.

For meaning is not one object among others, not a proton or a quark waiting to be revealed by ever more powerful instruments of observation. Meaning consists, rather, in the way the world is disclosed to creatures who act, choose, suffer and hold one another responsible—it is disclosed in the watching of a sunset, the whispering of a prayer, the reading of a novel, the refraining from cruelty, the observation of a distant planet. Science arose within this already meaningful world and abstracts from it in order to isolate causal processes. To mistake that abstraction for a complete account of reality is not hard-headed realism, but conceptual confusion.

Once this confusion is recognized, the deflating rhetoric, e.g., the claim that “from the scientific viewpoint, life has absolutely no meaning,” loses its force. Meaning is not delusional because physics is indifferent, just as fear is not delusional because it has neural and hormonal correlates.

A father who supports his daughter, an artist who crafts a novel, or a citizen who struggles for justice is not mistaken to think his life meaningful simply because such meaning is not measurable under a microscope. These activities belong to a different domain of understanding, one concerned with significance, value, and obligation, and they are best approached through philosophy and art rather than through physics or chemistry.

It is right to celebrate science, but dangerous to turn it into an imperial creed with an austere metaphysics of reductive materialism. The world is a big place. There’s enough room for science and religion, for physics and poetry, for chemistry and phenomenology, for matter and meaning.

Bo Winegard is an Editor of Aporia.

Become a free or paid subscriber:

Like and comment below.

Yuval Noah Harari is an obnoxious pseudointellectual and Sapiens is one of the worst books on Human Evolution & History ever written

In the past I would have agreed with Yuval. But I invite anyone that thinks life is meaningless to have a daughter. Seeing her growing up and smiling has answered what dozens of philosophy books haven’t.