Our Almost Perfect Meritocracy....

Simon Wright tells us what twin studies reveal about the success of modern societies

Paid supporters can listen to my narration of this article here.

For this week only, we’re giving you 50% off a yearly subscription. For just $25, you will receive a whole host of benefits and support our project:

Written by Simon Wright.

Life isn’t fair. Some people are born with more than others and they stay rich. If you’re born poor, you are likely to stay poor. The rich get richer, the poor get poorer. Not only is this unfair, it’s inefficient. After all, what we want is the best and most productive people for the job. We want meritocracy. And we can’t have that if Sebastian’s rich dad’s rich friend keeps giving him all these prestigious internships and a flat to live in rent free whilst he works for nothing. Sebastian is a woefully under-qualified, privately educated twat who epitomises everything wrong about [insert rotten country].

Except this isn’t really true. I mean, the Sebastian part is true. Many of us know of a truly talentless rich kid or two who soared to senior partner despite spending much of their education licking their elbows. God, you’re a twat, Sebastian. But the Sebastians of the world are outliers. The truth is that when we consult objective metrics, our convenient little story falls to pieces. The brilliant sociologist Peter Saunders has already written beautifully for this publication, asking why everybody lies about social mobility, including supposedly right-wing politicians. All of which has left Peter feeling somewhat depressed:

For the best part of thirty years I’ve been trying to explain to governments, educationalists, journalists and other opinion-leaders that our system is to a large extent meritocratic, and that the social class gap in educational and occupational achievement is largely down to differences of ability rather than differences of opportunity. But I’ve got nowhere. Politicians don’t want to know. They feel much more comfortable telling people that the system is unfair than explaining to them that some kids are simply brighter than others, and maybe their kid isn’t one of them.

I urge you to read the full piece here:

What I want to do in this sequel article of sorts is to examine the hard evidence that we live in a meritocracy. And maybe I’ll convince you that sending your children to private school is a waste of money along the way.

Economics 101

According to economics 101, our original story doesn’t make much sense. If firms are systematically hiring people that aren’t the best for the job then they will be less profitable. Not only is this an incentive not to engage in hiring rich kids just because they are rich, in a competitive market it’s imperative! Hiring a family friend for your cheese cake company even though he’s not very good at his job? Well, your competitor isn’t. Now he can undercut you, selling for less than you can afford to charge because your family friend is a weirdo who keeps sticking his penis into the cake mixture. Despite watching this on the CCTV, you can’t fire this cake-fucking maniac because his dad gave you a start-up loan.

Note: this isn’t to say that there can’t be any nepotism or inefficiency in the real world. Market imperfections mean a lot of things can happen here on earth that don’t exist up in the platonic realm of a perfectly competitive market, where prices are perfectly flexible and profits are knife-edge. But we don’t expect to see such systemic insanity. However, a question quickly emerges.

Why is it then that we see children of rich parents earning more than children of parents who aren’t as well off? There are two possible answers. The first is that our economic theory is wrong, or not applicable to the real world; maybe the incentive of profit and the forces of competition aren’t strong enough to drive out the lure of hiring rich children. The second is that children of high income parents really are more productive than the children of low income parents. Perhaps they are getting higher paying jobs because they are better suited to these roles? (We will come back to the question of if this is because of richer children having unfair advantages).

So how do we work out which theory is correct? The obvious answer is to try and statistically control for ability and see how well a family income predicts children’s income. Fortunately, this has recently been done using two surveys in the US: the NLSY79 (surveying people born between 1957 and 1967) and the NLSY97 (people born 1980-1984). Before we control for ability, the NLSY79 survey shows that doubling your parent’s income will increase a child’s earnings by 23%! And your parents having an extra year of education increases your income by an average of 4%, not very meritocratic. Things do look a little better for people born in the later group — there doubling your parent’s income will only increase your income by 9% while the effect of your parents getting more schooling stays at 4%.

Okay, so what happens when we control for ability? We’re going to do this by using IQ as a proxy for ability, we’ll talk more about that in a second. Well, the effects for family income roughly halve, to 13% and 5% for NLSY79 and NLSY97 respectively, and the effect of parental education disappears into statistical insignificance! Let me repeat that: once you control for IQ, if you were born between 1980 and 1984 (our most recent sample), then doubling your parent’s income would only increase your income by 5%! That is pretty damn meritocratic. If we add in a control for your years of education (another proxy for ability) this doesn’t change much, except to shrink the effect of IQ a bit, but it remains more than twice as important as family income in NLSY79 and 3.5 times as important in NLSY97. (For the nerds out there, we can compare the relative importance of various factors using something called “standardised Betas”).

The Role of IQ

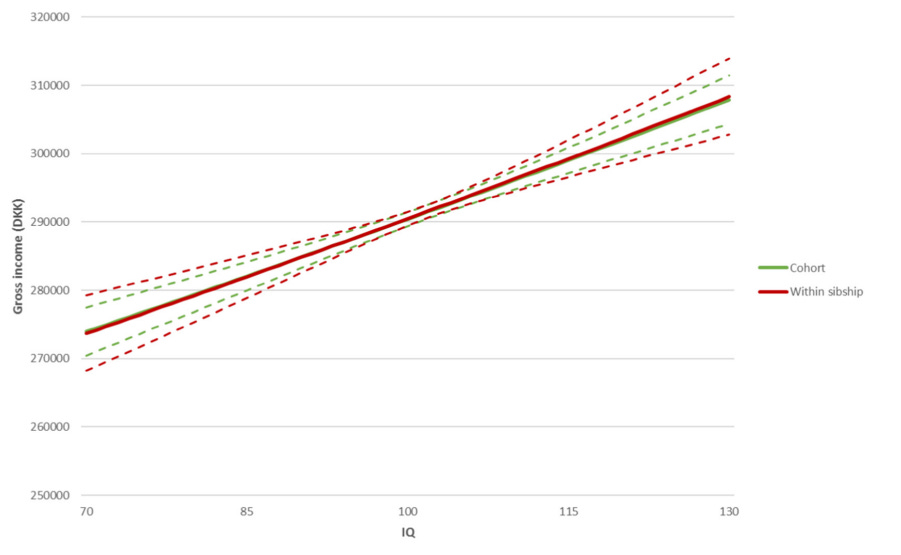

Some people think that IQ has been “debunked” or is “pseudoscience”. These people are wrong. The vast majority of experts support the notion of a general factor of intelligence. More specifically, when it comes to if IQ is a good proxy for ability, we have extremely good evidence that it is. One recent example comes from “within sibling analysis”. Put simply, we find that for a pair of siblings, the brother or sister with a higher IQ will earn more on average than the sibling with a lower IQ. Not only that, but a 1 point higher IQ will result in the same average income difference between two siblings as between two random people, after controlling for a few variables such as age. This removes any confounding effects with childhood as an explanation for the association between IQ and income.

Still, what if high IQ parents have high incomes and good connections, which leads to their children getting higher incomes. In other words, the cause of those children’s high incomes could have nothing to do with their IQ. But, as we’ve just demonstrated, this is clearly not true because we now know that higher IQ children will do better than lower IQ children, even when they share the same parents! Remember, however, that such statements must be carefully caveated with the phrase: on average. It does not matter if you think this isn’t true for 90% of the siblings you personally know.

Two Moves Left

There are two interesting replies we can now make.

What if high income parents are giving their children an advantage in IQ? Maybe they are sending their kids to private school, or having more books at home etc.

We might actually be overestimating the role that family has so far! We’ve controlled for IQ as a proxy for ability, but there are other things that contribute to ability as well, like conscientiousness and dedication. People also have different interests, which will contribute to their career choices. All these are likely to have partially genetic explanations beyond IQ.

To analyse these objections, we need to introduce a few terms. I’m going to stick to giving you an intuitive understanding of what these terms mean. (If you want more detail, I suggest reading chapter 10 of Charles Murray’s brilliant book Human Diversity).

Variance: A measure of how spread out our data is. In our example, the wider the differences in income between people the higher the variance.

Heritability: the share of the variance in a trait (e.g income) that is attributable to genes. It's important to note that this is not a fixed quantity, and the wider the range of environments, the lower the heritability. For example, if we were to plant some seeds and subject them all to identical environments (same sunlight, water, soil etc) then the heritability of the plants height would be 100%. If we start to give different plants different levels of sunlight, then some of the variation in height would be because of that, so heritability would drop. (Again, nerds might be interested in learning about broad vs narrow heritability, a rabbit hole I’m not going to go down here).

Common/shared environment: Any environmental influence that is shared by twins, such as books in the home, the school they attend, income etc. Technically this is only to the degree that these are making siblings more similar. For instance; if both siblings had a parent very involved in their academic achievement and this caused one child to excel but the other child to rebel, it would not be captured by shared environment.

Non-shared environment: Any other environmental influences on a trait that is not shared by siblings. Such as if their parents treat them differently, different friendship groups (to the extent differences in friendship groups are not caused by genes), accidents that may affect them etc. When we try to estimate this, it is impossible to separate the construct from measurement error, which includes errors in reported income, and also the degree to which our construct differs from our measure. For example if we want to measure the heritability of lifetime income, but we only have data for someone’s 5 year income, then the extent to which these two things differ is measurement error.

I won’t dive into the maths of how we estimate these things, but essentially by looking at the differences between identical and non-identical twins we are able to come up with estimates (key word) for the share of the variance in a trait (e.g income) that is attributable to genes, shared environment and nonshared environment (+ measurement error). Because psychologists aren’t the most creative bunch in the world, we call this type of analysis “twin studies” or more accurately “twins reared together”.

So, armed with our twin study methodology, what can we say about the first argument. To save you scrolling, that was:

What if high income parents are giving their children an advantage in IQ? Maybe they are sending their kids to private school, or having more books at home etc.

We have some surprising findings here from eleven studies. These studies conclude that the heritability of IQ increases with age (another rabbit hole for another day) and reaches roughly 70% by age 17. Shared environment explains none of the variance! Remember, this includes all of the environment that you share with your siblings, not just effects related to income inequality between parents. (Another nerd note: for those of you who have heard of something called Scarr-Rowe effects, there is no evidence for its existence in the West outside of the United States. Here is a study specifically for the UK. Indeed, recent evidence suggests it doesn’t even exist in the US.)

What about our other argument? It was:

We might actually be overestimating the role that family plays.

In other words, using IQ actually causes us to miss something. Looking back to our US survey data we can see that IQ alone accounts for 15 or 17% of the variance in income, depending on the survey. If we look at twin studies in the US we can see that the average estimate for the heritability of income is 41%, with the common environment explaining just 9% of the variance in income. To add a bit of speculation into this finding, the 41% heritability is likely an underestimate for lifetime earnings: US studies measure either annual earnings or wages, but earnings over a year are likely to be more subject to random fluctuations than earnings over a lifetime. As pointed out when we introduced our terms, this discrepancy between what we are really interested in (lifetime earnings) and our measure (annual earnings) will be picked up in our non-shared environment estimate. From the same literature review we have estimates from Sweden showing that heritability is much higher for income over 20 years than income over 5 years, whilst the role of common environments remains either at 0% or shrinks to 0%.

A more recent study found that shared environment plays no role in personal income but that it explains 15% of the variance in household income (heritability estimates of 34.2% and 26.6% respectively), which suggests that your parents’ socioeconomic status (and other shared environment factors) may play a role in who you marry!

I want to address a final more nuanced point tangentially made by the likes of Noam Chomsky: What if we are measuring the wrong outcome here? Maybe having rich parents allows you to not care about money and instead focus on doing what you love. We have two ways to address that question. First, we can look at “occupational attainment” as an outcome measure, this essentially measures how prestigious your job is. Turning back to our US surveys again we find that IQ is at least six times as important (as parental SES) in explaining occupational attainment.

Our second method is to see if a shared environment has any influence on how happy people are. Shared environment seems to play almost no role here and studies which estimate the part of subjective well-being that is stable over time tend to find very high heritability estimates (72-95%). The evidence here again suggests that your job and how happy you are is largely the result of genes, and not how rich your parents were.

Concluding Thoughts

IQ is a far more important predictor of income than how rich one’s parents are.

Within industrialised countries, intelligence and income differences can be largely explained by genes.

The role of a shared environment in determining income is very small and this will incorporate all effects of the shared environment, including how loving, nurturing and smart your parents are, not just their income.

Short of kidnapping children and forcing them into communal learning facilities you probably aren’t going to get rid of these environmental effects. Of course, this does not mean that income inequality is immutable. What it does mean is that, to a large extent, market income reflects people’s innate ability and choices. Hence, you probably will not reduce income inequality by providing the children of low income families with a better childhood environment (better schooling, giving parents money, and so on). If you want to reduce income inequality, you will have to do it the old fashioned way: tax the rich, pay the poor. If you can’t reduce income inequality in the market then don’t, reduce income inequality after taxes and transfers instead. I will also offer that we may have more luck tackling wealth inequality which seems to be more affected by parental socioeconomic status than income, although heritability estimates still suggest that shared environment plays a fairly small role in the value of household assets or whether someone owns a home (10% and 17.5% common environment respectively).

Simon Wright is an independent researcher looking to embark on a PhD in economics. He can be contacted at simonwright50392@protonmail.com

Help us grow something special!

If you’d like to help support and grow ISF, become a supporter today from only $5 per month and get:

Exclusive articles

You will get to hear my sweet dulcet tones as I narrate every article we upload. Worth the price of admission alone.

Livestreams with myself, Jonny Anomaly, and other guests

Submit questions to guests & gain access to the 3 special questions we ask guests.

Early access to podcasts & your name in the credits

You can also become a Patron (where we have more benefits on offer).

Nice pile of shattered illusions you've got yourself there, Simon.