Orwell's Inner Party: The man behind the myth

Orwell is the first serious author many of us read, probably at school, and unlike Shakespeare who is often taught extremely badly, we do not hate him for the experience.

Written by J William Browne.

I give all this background information as I do not think one can assess a writer's motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject matter will be determined by the age he lives in - at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own - but before he ever begins to write he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, in some perverse mood; but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write.'

Why I Write

— George Orwell, 1946

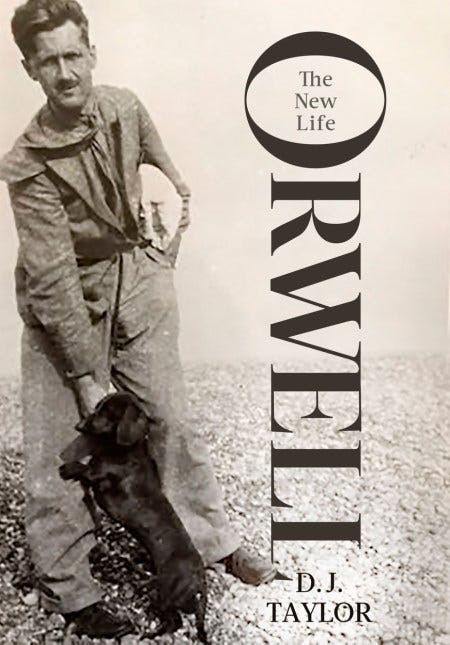

Though he insisted that no biography of his life be written, George Orwell often told his readers who he thought he was. I do not write ‘who he was’, because the myth of Saint George has one primary author, and that is the saint himself. One rarely reads a page where a small detail of his life isn’t to be found, like a sprinkle of breadcrumbs for would-be biographers. It is a trail that seems to lead in circles, for the origins of saints and their myth’s remain elusive. But as he wrote of Gandhi, ‘saints should be judged guilty until they are proved innocent’. It is this guilt or innocence which D.J. Taylor has once again set about proving in a fresh study, Orwell: The New Life.

The new biography follows Taylor’s seemingly definitive Orwell: The Life, released on the enduring English radical’s centenary in 2003. Reviewing this edition ten years ago, I recall thinking that the first study was hindered by excessive scepticism of Orwell’s literary honesty and by frequent and indulgent references to William Thackeray, about whom Taylor has also written a biography. At the time, I was a recent convert to the myth of Saint George and was sensitive to criticisms of him. I considered him “my author”. I soon discovered that this sense of a unique relationship with Orwell was itself rather commonplace. Christopher Hitchens, a talented and mischievous disciple of Saint George, described reading Orwell’s work as the feeling of being personally addressed.

Taylor has as powerful a claim as any to George Orwell as his author. He has not only read and scrutinised his author’s work to a far greater depth than any previous biographers, but also the finer details of his life and most importantly, his literary muses. Taylor can draw attention to the similarities between scenes in Thackeray and Orwell, and document the partial borrowing from many other turgid and forgettable novels besides. In doing so, Taylor gives a sense of what the fierce literary critic Harold Bloom called “the anxiety of influence”: that artistic invention is often motivated by a creative misreading of an author’s literary influences. Discovering these new insights into the inspiration for favourite works such as Down and Out in Paris and London and ‘A Hanging’, I reproached my younger self for dismissing Taylor’s numerous references to Thackeray.

To make a valuable contribution to the burgeoning market of Orwell Studies, particularly as the copyright runs out on his books, one is required to do a tremendous amount of reading to discover the secrets of a writer who was extremely well read: Dickens, Gissing, Joyce, Maugham, Wells, Swift, Housman, Kipling, to name a few of his important influences. As a writer and literary critic himself, one would imagine that D.J. Taylor was already familiar with these authors before writing the first biography published in 2003, but as he has noted upon The New Life’s publication, his relationship to Orwell has changed in the past twenty years, as one can assume the depth of his wider reading has too. It is upon this bookish effort, as well as an understanding of wider historical and political atmosphere to which Orwell responds with much greater certainty in print than in his private letters, that Taylor is wise to the unreliable narrator of Orwell’s fragmented autobiography. And, moreover, the ideological revisions he would make to yesterday’s black thoughts with today’s red pen.

In the excellent Arena documentary series from 1983, where one glimpses the living, wheezing man behind the typewriter through interviews with those who knew him, his close friend Tosco Fyvel summed up the challenge of the biographer best:

As Orwell was such an autobiographical writer, one could say that there was an element of fiction in all his autobiography and a strong element of autobiography in all his fiction.

The statement is a compelling summons for scholars and students of his work alike, for there are many periods of his life when Orwell goes missing altogether. In this new biography Taylor presents recently discovered caches of letters to love interests which reveal his tendency for philandering, but also where he was during gaps in his diaries and most importantly, what he was reading. Though there is little new information that will change an analysis of Orwell’s most important body of work, the letters do provide an insight into the authors whom he was reading as he wrote what Taylor calls the most ‘Orwellian’ novels, A Clergyman’s Daughter and Keep the Aspidistra Flying.

Still, blank pages in the biography remain. We know little of Orwell’s immediate reaction to the British Empire during his five years as a young Imperial Policeman in Burma and still less of the two failed novels that he attempted as a ragged trousered bohemian in late 1920s Paris. Little that is, other than the carefully edited accounts written many years later, which were written when Orwell’s attitude had undoubtedly altered in response to both experiences in the crucible of ideology that was the first half of the 20th century.

The Road from Bank to Mandalay

Burma is a mystery which fascinates many scholars of his work, including Taylor. It was the start of a journey from the Eton schoolboy of snobbish privilege, christened Eric Arthur Blair, to the oppressed outsider, George Orwell, who found virtue and warmth in the filthy underbelly of society. His five years in the East were also the beginning of a literary maturity, providing the material for two of his most powerful essays, ‘A Hanging’ and ‘Shooting an Elephant’.

Despite Taylor’s best efforts, poring over ancient copies of the Rangoon Gazette to confirm that Lt. Blair saw a man hanged in Lower Burma, or to find literal missing elephants which the author claimed later to have shot and glimpsed the horror of imperialism in the grisly act, the mystery of whether either happened as described remains.

‘A Hanging’ describes the execution of a native prisoner by the British and hinges upon on a seemingly insignificant detail which becomes a moment of revelation when seen through Orwell’s eyes:

It was about forty yards to the gallows. I watched the bare brown back of the prisoner marching in front of me. He walked clumsily with his bound arms, but quite steadily, with that bobbing gait of the Indian who never straightens his knees. At each step his muscles slid neatly into place, the lock of hair on his scalp danced up and down, his feet printed themselves on the wet gravel. And once, in spite of the men who gripped him by each shoulder, he stepped slightly aside to avoid a puddle on the path.

It is curious, but till that moment I had never realised what it means to destroy a healthy, conscious man. When I saw the prisoner step aside to avoid the puddle, I saw the mystery, the unspeakable wrongness, of cutting a life short when it is in full tide. This man was not dying, he was alive just as we were alive. All the organs of his body were working — bowels digesting food, skin renewing itself, nails growing, tissues forming — all toiling away in solemn foolery. His nails would still be growing when he stood on the drop, when he was falling through the air with a tenth of a second to live. His eyes saw the yellow gravel and the grey walls, and his brain still remembered, foresaw, reasoned — reasoned even about puddles. He and we were a party of men walking together, seeing, hearing, feeling, understanding the same world; and in two minutes, with a sudden snap, one of us would be gone — one mind less, one world less.

If French Literature gave the world ‘Proustian Moments’, this is what we might call the English equivalent: an ‘Orwellian Epiphany”. It was a characteristic of his writing to employ a series of individual human moments as apparent revelations, used to make grand abstractions on the state of England, her Empire, and the forces that would seek to destroy them. And though the political moral Orwell divines is a sober reflection from his writing desk rather than the Damascene conversion we are presented, the immediacy and pathos remain hard to refute.

For the biographer of Orwell, these moments are important. His epiphanies represent developments in his political beliefs and personal myth, both of which formed the mature writer who is revered today.

Returning from Burma on leave, Orwell scandalised his respectable family by stating that he was throwing in his job in the East to become a writer. He had also started to tramp. In the footsteps of his idol, Jack London, the old Etonian began sleeping rough in Trafalgar Square, fraternising with prostitutes and vagabonds in the Latin quarter of 1920s Paris and made a habit of braving the end of many a public schoolboy’s nightmare, the ‘Spike’ (the casual ward of a workhouse that functioned like a kind of voluntary prison for the homeless).

In one of the insightful vignettes that punctuate Taylor’s chapters we read of how Orwell’s ‘Duke of Windsor cockney’ accent would give him away to the tramps and navvies whom he associated with in the lowest of common lodging houses, if his expensive flannel trousers from the family tailor in Southwold hadn’t already. Previous biographers Bernard Crick and Michael Shelden have contended that his tramping was simply a search for revelations to write about for a genteel audience. Taylor however takes a more charitable view, which is far more convincing. In my opinion, Orwell’s descent into squalor was a conscious crossing of the floor, from the sweet smelling cant of the oppressors, to the ‘sub-faecal’ sincerity of the oppressed.

Wigan Pier

It was however in 1936 that Eric Blair began fully to shed his skin in response to what he saw in the slums of the industrial north and Revolutionary Spain. In the most famous of his epiphanies, Orwell once again saw a political vision: not on the Road to Damascus, but on The Road to Wigan Pier. Typically edited from the original for greater effect, a scene glimpsed during a walk around a slum backstreet noted in his dairy, Wigan Pier was the book in which he became an overtly political writer:

The train bore me away, through the monstrous scenery of slagheaps, chimneys, piled scrap-iron, foul canals, paths of cindery mud criss-crossed by the prints of clogs... As we moved slowly through the outskirts of the town we passed row after row of little grey slum houses running at right angles to the embankment. At the back of one of the houses a young woman was kneeling on the stones, poking a stick up the leaden waste-pipe which ran from the sink inside and which I suppose was blocked. I had time to see everything about her – her sacking apron, her clumsy clogs, her arms reddened by the cold. She looked up as the train passed, and I was almost near enough to catch her eye. She had a round pale face, the usual exhausted face of the slum girl who is twenty-five and looks forty, thanks to miscarriages and drudgery; and it wore, for the second in which I saw it, the most desolate, hopeless expression I have ever seen. It struck me then that we are mistaken when we say that ‘It isn’t the same for them as it would be for us’, and that people bred in the slums can imagine nothing but the slums. For what I saw in her face was not the ignorant suffering of an animal. She knew well enough what was happening to her – understood as well as I did how dreadful a destiny it was to be kneeling there in the bitter cold, on the slimy stones of a slum backyard, poking a stick up a foul drain-pipe.

What links both these revelatory insights is an appeal for a common humanism, as made from a distance of class and culture from their subject. It is less ironic than simply characteristic of a writer who rejected the title of an intellectual, that Orwell reduced himself to the level of a tramp or out of work miner to discover the source of what would come to define his political attitude: common decency.

Spending time in the lowest of lodgings, with full chamber pots beneath the breakfast table and crawling with black beetles, or lying prostrate at the coalface as near-naked miners blackened to their eyelids set about their morning’s shift, Orwell found a cause for his appeals to common decency in Democratic Socialism. He wasn’t, however, one to join a cause without scepticism:

One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words ‘Socialism’ and ‘Communism’ draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature Cure’ quack, pacifist, and feminist in England.

As a political writer during this period, Orwell was still shaking off his upbringing in an act of class rebellion. Described by friends as a “Bohemian Tory” and “Tory Anarchist,” his anthropology was still that of an upper class gentleman’s perspective of 6 feet and 2 inches, heights above the anaemic working class troglodytes he briefly walked amongst like the giant from Gulliver’s Travels. For in Wigan Pier Orwell bridges the gulf of class at the shortest possible point. As Taylor asks, where in Wigan Pier is northern culture? The comedians, the music halls, the dreary Methodism which preached such a political application of the gospel? Their absence is particularly noticeable in that these were topics which he would become so absorbed in towards the end of his life, essentially founding a new academic discipline in cultural studies such was his interest in working class and popular culture. But as it was, under the pressure of the political decade that was the 1930s, Orwell harnessed his typewriter to the socialist cause. It was a cause he would die believing, and indeed very nearly die for, in the Spanish Civil War.

That Arid Square

On that arid square, that fragment nipped off from hot Africa, soldered so crudely to inventive Europe;

On that tableland scored by rivers,

Our thoughts have bodies; the menacing shapes of our fever

Spain

— W.H. Auden, 1937

That Arid Square remains a heated subject nearly 90 years on. Despite the ongoing retrospective disputes about Revolutionary Barcelona, Taylor, like Orwell, merely observes from above. He is clearly well read on the subject, providing insight into the confused ideological ferment of the loyalist forces to evaluate Orwell’s own restricted view of events. Objectivity can stifle the imagination, however. What this essential section of the biography lacks is a judicious amount of indulgence of Orwell and his reportage from Spain. Orwell’s fight against fascism, his having been shot in the trenches of that fight, and his having fled to France to avoid execution by his own side for the wrong ideological associations — these were the most defining experiences of his life.

It was Spain that Orwell talked and wrote about incessantly right up to his death; Spain where the genesis of Nineteen Eighty-four and Animal Farm are to be found; and Spain where the enduring saint started to perform miracles in his works. Though it is a period piece, Homage to Catalonia is one of the most re-readable of Orwell’s books, a point in his development as a writer where his craft of political writing had become an art. The Spanish chapters feel light on the nuggets of Taylor’s literary insight and analysis for a period in his life where Orwell’s mature style asserts itself with immense power and clarity, nuggets which the biographer provides in assessing his earlier and later life. Taylor’s book being a biography and not a literary investigation, this is less a criticism than a greedy desire for more.

It is in Homage to Catalonia that we are treated to another moment of epiphany, perhaps the only one that took place more or less as described. Here Orwell narrates being shot through the neck by a fascist sniper in the dawn trenches of Aragon Front, and presumes that he is dying:

As soon as I knew that the bullet had gone clean through my neck I took it for granted that I was done for. I had never heard of a man or an animal getting a bullet through the middle of the neck and surviving it. The blood was dribbling out of the corner of my mouth. 'The artery's gone,' I thought. I wondered how long you last when your carotid artery is cut; not many minutes, presumably. Everything was very blurry. There must have been about two minutes during which I assumed that I was killed. And that too was interesting—I mean it is interesting to know what your thoughts would be at such a time. My first thought, conventionally enough, was for my wife. My second was a violent resentment at having to leave this world which, when all is said and done, suits me so well. I had time to feel this very vividly. The stupid mischance infuriated me. The meaninglessness of it! To be bumped off, not even in battle, but in this stale corner of the trenches, thanks to a moment's carelessness! I thought, too, of the man who had shot me—wondered what he was like, whether he was a Spaniard or a foreigner, whether he knew he had got me, and so forth. I could not feel any resentment against him. I reflected that as he was a Fascist I would have killed him if I could, but that if he had been taken prisoner and brought before me at this moment I would merely have congratulated him on his good shooting. It may be, though, that if you were really dying your thoughts would be quite different.

England, His England

Avoiding death by fractions of an inch, Orwell was patched up in a field hospital but would never recover his voice which was irreparably damaged, something he made up for in spades as a polemicist with a pen. After fleeing to the French border with his wife to escape the Communist counter revolution and a likely second and this time fatal bullet from his own side for sharing a dugout with the wrong ideological bedfellows, Orwell returned to the world that suited him so well, his England. He spent the next two years fighting with partisan London publishers to get his accounts of the war in Spain into print, before briefly travelling to Morocco to restore his health and write the most typically English of his novels, Coming Up for Air.

It is a story in which the oncoming world war slowly rumbles towards its protagonist, George Bowling, who tries in vain to escape to a past that exists only in memory. In considering his tendency towards epiphany, it is worth noting that Bowling’s journey in time its triggered by a Proustian moment. While reading a newspaper headline that reminds him of the church services of his boyhood, mixed with the sound of traffic and pungent smell of horse manure, Bowling is overcome by nostalgia. But it is Orwell who is speaking through Bowling here:

The past is a curious thing. It’s with you all the time. I suppose an hour never passes without your thinking of things that happened ten or twenty years ago, and yet most of the time it has no reality, it’s just a set of facts that you’ve learned, like a lot of stuff in a history book. Then some chance sight or smell, especially smell, sets you going, and the past doesn’t merely come back to you, you’re actually in the past. It was like that in this moment.

This is perhaps the best insight into how Orwell’s epiphanies formed in his memory, to be edited later at his writing desk. But much as his previous work had made a habit of these moments of revelation, in Burma, Wigan, and Spain, the mature Orwell was beginning to develop from Saul to Moses; from epiphany to prophecy. The night before the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was announced, he had a premonition:

I don’t quite know in what year I first knew for certain that the present war was coming. After 1936, of course, the thing was obvious to anyone except an idiot... But the night before the Russo-German pact was announced I dreamed that the war had started. It was one of those dreams which, whatever Freudian inner meaning they may have, do sometimes reveal to you the real state of your feelings.

The war invigorated Orwell’s love for England, her quiet and peculiar ways. It also invigorated his literary output. After an initial false start of two years at the BBC, the 1940s were to be Orwell’s most prolific decade. And where the Spain chapters fall short, Taylor excels on the wartime and post-war period. Warm meetings with Graham Greene and P. G. Wodehouse are discussed as well as his sense of finally being recognised as a serious writer. We see the indulgent austerity of his day-to-day life, even by the standards of wartime, and a habit of unburdening intimate details in letters to near strangers.

It was through this habit and at this point in his life more than any other that we see Orwell reinterpreting the saint he sought to judge, Gandhi, to ‘be the myth you wish the world to see in you’. Recounting sexual encounters to dinner party company: of how his wife Eileen had allowed him to hire a teenage Arab prostitute in Marrakech, or asking a pointed question of fellow writer Anthony Powell “had he ever had a woman in a park?”, to set up the reciprocal question and confirm that he had, as ‘there was nowhere else to go.’ As Taylor points out:

The revelation trails off into something close to self-pity: a better ordered society would provide a venue in which Orwell and his girlfriend could go off an have sex to their hearts’ content. And yet the lack of one is equally important: clearly part of him actively wants to be a ground down bedsit-dweller whose landlady has forbidden his women friends the house, or at any rate to be able to talk about his predicament to other men.

It is in keeping with a response to another dinner party question, ‘what quality would you most wish to possess’, to which Orwell’s answer was ‘to be irresistible to women’. These glimpses of Orwell with his guard down are irresistible. With no express memoir, recording of his voice, and nearly everyone who knew him now dead, Orwell the man remains an elusive figure. A particular highlight in this book is an interlude between chapters, ‘Orwell and his World’, where Taylor attempts to answer the question his subject seems to constantly evade, even in his own biography: ‘what was Orwell like?’

Animal Farm

His first biographer, Bernard Crick, once made the point that people tend to read Orwell backwards. We start with Nineteen Eighty-four and Animal Farm, and if we are lucky, stick around long enough to discover his literary criticism, political essays, social novels and reportage. As such, it is this period of The New Life that is likely to be the most vital. Orwell did not like to give too much away when a manuscript was still in progress, but we learn from Taylor of the undercooked draft of Animal Farm that he shared with the young translator Michael Meyer in 1943. Meyer was unimpressed and astonished to read the finished novella two years later.

Though this and many other manuscripts sadly do not survive, we learn of important moments in Animal Farm’s development: the apparent moment of inspiration, of Orwell seeing a small boy leading a giant carthorse down a country lane and wondering what would happen if the animal asserted itself, to the amendment made to the part of the story where the farm windmill explodes and the animals throw themselves to the floor in terror. The first draft read ‘all the animals, including Napoleon’. In the second, Napoleon is the only animal to stand his ground. This is a reference to Stalin remaining in Stalingrad at the height of the Nazi siege in 1942-1943 and typical of Orwell’s sense of fair play even to the gravest of enemies.

What is missing from this section of The New Life is the influence of his first wife, Eileen. In the first biography, Taylor seems to hint at her role in the development of Animal Farm, while Sylvia Topp has argued cogently for her influence on Animal Farm in her biography of the other side of the story, Eileen: The Making of George Orwell. Eileen does however get a sympathetic hearing throughout. Taylor is not coy in his criticism of Orwell’s under appreciation of his extraordinary first wife, who tragically died in a routine operation in 1945 while her husband was away in France, reporting on the war.

2 + 2 = 1984

George Orwell was never truly well. Throughout his short life he had wrestled with attacks on his lungs, including bouts of tuberculosis, made worse by his habit of heavy smoking and heavy writing when he ought to have been at rest. By the end of the war, he was extremely ill and increasingly delicate, something which his biographer picks up in almost every mention of Orwell from this period. In 1946, with the assistance of a nanny to look after his infant son Richard, whom he and Eileen had adopted shortly before her death, Orwell moved to the Isle of Jura in the Inner Hebrides, partially to escape the demands of London literary life, partially to escape what was a prime target for an atomic bomb. Orwell had been dreaming for many years for an escape to one man’s island solitude.

Moving to a house seven miles from the nearest road and days from a doctor seems a foolish act for such an ill man, if not a dark one of actively hastening his death. Unlike many others, Taylor does not believe this act to have been a consciously morbid one, but rather Orwell being Orwell, impractical and stoic to the last.

By 1948 with the manuscript part-finished, we read of how Orwell would have sent Nineteen Eighty-four down the memory hole should he have died before his novel was complete. Like the other writer that exercised so much influence on the 20th century, and who like Orwell has given his name to a state of affairs he would have hated, Franz Kafka also instructed that his unfinished manuscript of a dystopian masterpiece, The Trial, should have been destroyed upon his death. Thankfully, both writers had their dying wishes ignored. But even though he survived to see his own novel published, in a typically uncharitable assessment of even his finest work, Orwell thought it to have been a poor execution of a good idea.

While flawed, Nineteen Eighty-four still acts like a doomsday clock, most recently topping the bestseller charts during the pandemic lockdowns and upon Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine. Its influence reaches far beyond those who have read it and is quoted like gospel at the faintest whiff of government overreach which seeks to fulfil the spirit of Orwell’s prophecy. Being the novel people are most likely to have lied about reading, Nineteen Eighty-four is also often clumsily wielded by those who would claim it for the Right and capitalism, as many in the U.S. did, along with Animal Farm throughout the Cold War (a phrase Orwell was the author of). But its author satirises something beyond old left and right, beyond good and evil.

In the decaying world of Airstrip One, Orwell exposes the undying allure of ideology obsessed with power. As Christopher Hitchens said of the novel’s enduring success, totalitarianism is nothing if not a cliché. It is a meaningful coincidence that the Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea was founded in the same year that Nineteen Eighty-four was finished in 1948.

Intriguingly, D. J. Taylor has suggested there is a ‘provisional aspect’ to Nineteen Eighty-four, which he believes to be an incomplete novel which could have looked quite different if its author had been well. It is a book without hope. Some who knew him towards the end of his life have said that Orwell knew he was dying as he was finishing Eighty-four, but always one to ignore his ill health, there is much to suggest that he was planning on living for ‘another ten years’ as he set out in a letter from this period. All the same, the shadow of death hangs over the book he went to Jura to write, and which Taylor seems to almost suggest killed its author.

How a Legend is Created

In the small hours of 21 January 1950, Orwell died alone in a ward of University College Hospital from a massive haemorrhage in one of his lungs. He had seemed to rally his health, and had been greatly cheered up by a hospital wedding to Sonia Brownell who was making plans to remove her husband to a sanitarium in Switzerland, but all who saw him during for the few months before his death could sense the end. As Taylor writes of two close, literary friends who regularly visited him near the end:

[The Doctor’s] staff believed he was not in pain, but psychologically he was at the end of his tether. [Malcolm] Muggeridge and [Anthony] Powell, walking around the hospital on the afternoon of Christmas Day, found him alone in his room, with Christmas decorations suspended incongruously from the ceiling — looking like a picture of Nietzsche on his deathbed, Muggeridge thought, and inwardly seething. And all the while “the stench of death was in the air, like autumn in a garden”.

A line, I suspect, that Orwell would have liked to have written himself.

Considering the fickle literary fashion that in ten years had reduced his beloved A.E. Housman, a titan of Victorian poetry, to something a boy in 1940 may consider ‘rather cheaply clever,’ Orwell asks of writers who fall from favour:

Why does the bubble always burst? To answer that question one has to take account of the external conditions that make certain writers popular at certain times.

We may ask the same question today: when will George Orwell’s bubble burst? Why are people like D. J. Taylor still publishing books about his life? In the essay, ‘Inside the Whale’, Orwell refers to Housman as a once ‘fashionable author’, by which he meant an author admired by people under the age of 30. Perhaps this explains the bubble’s continued rise.

Orwell is the first serious author many of us read, probably at school, and unlike Shakespeare who is often taught extremely badly, we do not hate him for the experience. Orwell was heartened to learn that one of his friend’s sons had enjoyed Animal Farm, subtitled ‘A Fairy Story’, as “there was no long words in it”.

I was however struck upon watching a discussion held by the Orwell Society with D.J. Taylor on this new biography, that Taylor was one of the youngest in attendance at 60 years old. The lesson to be drawn is that Orwell is a writer who speaks to all ages; you don’t need to be young to enjoy books with short words. It is the force he conveys with his simple prose, the moral clarity of exposing the naked brutality of power, that is the reason he still commands so much influence and respect.

Malcolm Muggeridge, reading through the obituaries of his friend, Orwell, who had now become a household name, commented that he could see “how the legend of a human being is created.” A legend which has endured, despite many a biographer’s best efforts to print the facts against his subject’s wishes. Orwell’s request that no biography of his life be written was mainly, I suspect, to allow the myth of ‘George Orwell’ to gather a little dust and increase the mystique around his work.

He wasn’t a saint, and isn’t found to be guilty or innocent in this latest study of his life. But paired with his earlier Orwell: The Life, with few living memories left to plunder, we now have as complete an image of the man as we ever will have. It may be that Orwell’s dying wish will now finally be respected, in that D.J. Taylor has written what are surely the definitive accounts of George Orwell’s extraordinary life.

Orwell: The New Life (2023) by D.J. Taylor is published by Constable.

J William Browne is a writer of fiction and a book reviewer on Substack and Twitter. He is currently writing a novel and collection of short stories that will both be published next year.

Consider supporting Aporia with a $6.99 monthly subscription and following us on Twitter.

„This is a reference to Stalin remaining in Stalingrad at the height of the Nazi siege in 1942-1943…“

What?

When I read this review, which I liked, I'm almost sure there was a part about Orwell's comments on The Road to Serfdom where he insisted central planning was still viable. Was this cut, or am I hallucinating? It was the most interesting part to me, where we could point out Orwell's biggest flaw: even before Hayek's crystal clear explanations, he insisted on socialism.