Luxury beliefs are not like luxury goods

A critical examination of the luxury beliefs hypothesis.

Written by Bo Winegard.

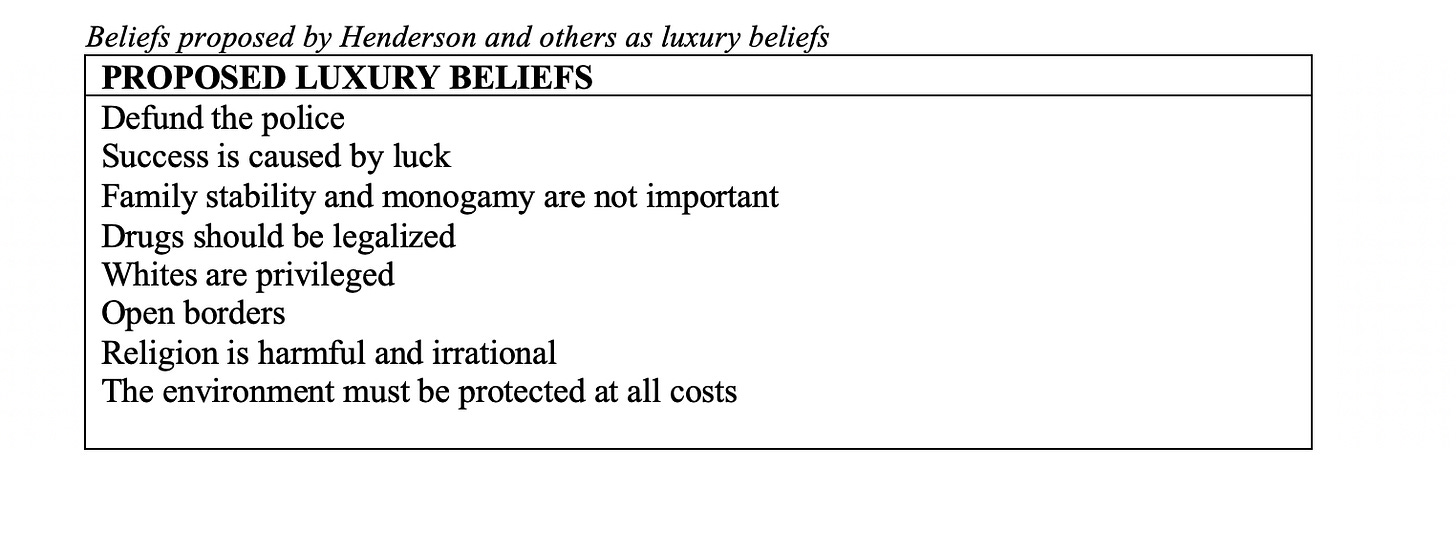

As enlightened and scientifically educated moderns, we applaud ourselves for having swept away the debris of antiquated superstitions—the witches, demons, spirits, ghosts, and omens that haunted our ancestors. Yet, we still seem to fill the world with strange ideas and convictions. During what some have called The Great Awokening, for example, bizarre beliefs such as that we should defund (even abolish) the police or that men can become women and women men solely through the power of psychological identification became so popular that they were propounded by mainstream outlets. Many intellectuals were perplexed by the rapid spread of these apparently implausible or unwise beliefs and attempted to account for their popularity.

Building from other less persuasive and less intriguing efforts, Rob Henderson forwarded perhaps the most interesting explanation: They are luxury beliefs. Like Ferraris, Rolexes, or refined and elevated tastes in art and literature, they are signals of wealth and status. Or, as Henderson wrote, they are “honest indicators of one’s social position, one’s level of wealth, where one was educated, and how much leisure time they have to adopt these fashionable beliefs.”

Having forwarded a similar though less compelling signaling account of some of these beliefs, I initially found the luxury beliefs thesis provocative and plausible (a reaction shared by many people). However, I have come to believe that the thesis is wrong and distorts our understanding of such beliefs.

To understand the luxury belief thesis and its problems, we first must understand the basic logic of costly signaling theory and how it applies to luxury goods.

Signaling is pervasive across the animal kingdom. We are all familiar with the gaudy plumage of a peacock or the impressive antlers of a moose, but animals signal in myriad subtle ways as well. In fact, communication requires signals and without them, organisms would be trapped inside their solitary worlds, unable to exchange information. But signals are not without drawbacks, the primary of which is that anything that can be used to signal can also be used to deceive. The bright red feathers of a cardinal might signal health and vigor to a potential mate, but a weak and sickly bird might grow bright red feathers to mislead a female. She wants to mate with a strong and healthy bird, but she is bamboozled into mating with a frail imposter. This possibility for dishonestly destabilizes signaling systems. How can one organism trust another organism’s signal?

One solution is the development of costly signals, or signals whose costs are prohibitive for cheaters. In the case of the cardinal’s plumage, if the weak and sickly bird cannot convert food into bright red feathers because the process is too metabolically expensive, then the signaling system will be reasonably reliable. Vibrant red birds, being those that are healthy enough to extract certain nutrients from foods and convert them into pigment, will be attractive to females; and pale red birds, being those too feeble or compromised to do so, will be unattractive.

The same principles hold for humans. We signal to each other incessantly. The most pervasive and important way is through language. Talk is cheap as the saying goes, and thus language is not only an effective tool for communication but also an effective tool for deception. On a date, it is not difficult to say, “I have several million dollars in my bank account.” Or “I am the son of a famous film studio executive” Or “My IQ is over 170.” Therefore, costly signals are crucial. A woman might not be impressed by a man’s declaration that his bank account is two million strong, but she probably would be impressed by his brand-new $250,000 Porsche or his $25,000 Rolex. These are costly (and therefore hard-to-fake) signals of wealth because only affluent people can afford to purchase them without making intolerable cuts to their monthly budgets.

Such costly signals in humans are also called luxury goods and are used primarily to signal wealth and social status. Other luxury goods include high-end clothing, expensive wines, jewelry, yachts, penthouses, mansions, vacation homes, personal chefs, et cetera. Anything that is relatively difficult (if not impossible) for poor people to display but relatively easy for wealthy people to display can function as a luxury good.

Not only goods but also tastes, preferences, behaviors, and other cultural displays can also function as costly signals of wealth and social status. For example, a sensitive and refined ability to distinguish among expensive wines might signal that one is wealthy. Only a prosperous person could have spent his time tasting innumerable wines to discern the difference between a Napa Cabernet Sauvignon and a Goldstrike Cabernet Sauvignon. Similarly, an admiration for modernist literature might signal that one is highly educated because only an erudite and intelligent person could have developed the knowledge to make sense of the nearly inscrutable writing of James Joyce or T. S. Eliot.

Luxury beliefs are like luxury goods or tastes because, according to Henderson, “These are ideas and opinions that confer status on the rich at very little cost, while taking a toll on the lower class.” Or put more technically, luxury beliefs are beliefs which are differentially costly: They impose a greater marginal cost on the lower classes than on the rich. From this perspective, defund the police is like a top hat because both are luxury symbols (though one is material and one is not) which reliably distinguish cultural elite from the plebeians and vulgarians who cannot obtain or display them.

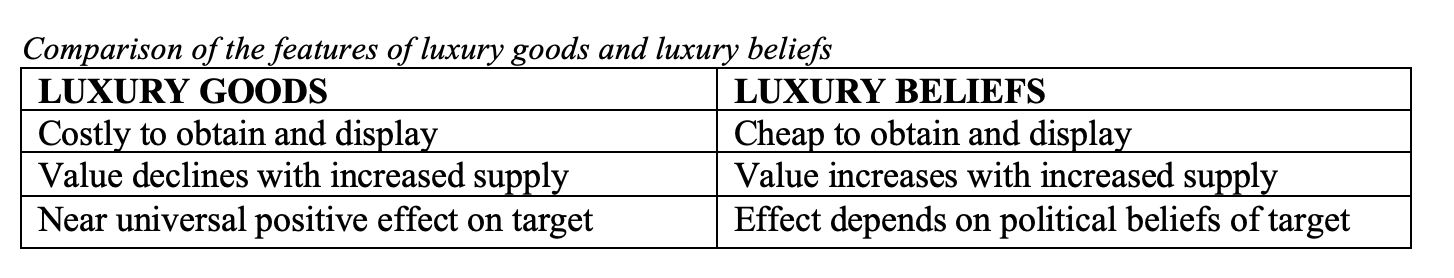

However, there is an important, even crucial difference between luxury goods and luxury beliefs which undermines the luxury beliefs thesis: luxury beliefs are not immediately costly. If Thomas is on a date with Sally, he can assert that he is an ardent supporter of police abolition and open borders without paying a single cent. Similarly, Jane can post on social media that she champions legalized drugs and polyamory without paying anything beyond the subscription fees to her internet provider and X.

Luxury goods are reliable precisely because they are too expensive for cheaters to acquire and display; but luxury beliefs are not similarly costly. Many do not even require the costs of an advanced education, since one can profess support for police abolition without grandiloquent speeches or a sophisticated understanding of police tactics.

Rob Henderson, being a sophisticated thinker, forwarded a reasonable answer to this problem: the cost is the effect the professed belief would have if enacted. Sure, extolling Black Lives Matter and denigrating the police may be costless for any particular individual, but if such beliefs became so widespread that they led to reduced policing, the lower classes would pay more than the wealthy, who curiously exempt themselves from the pleasures of diversity by living in relatively homogenous neighborhoods that are often protected by steel gates and private security forces. The same applies to other luxury beliefs such as open borders. Immigration does not hurt the affluent; in fact, in the short-term it likely helps them. But it hurts the poor by lowering their salaries because it increases the supply of cheap labor.

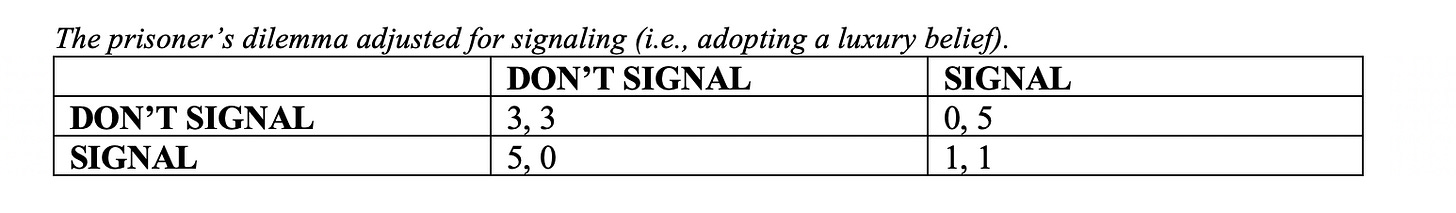

Although this proposal is not without merit and explanatory power, it does not support an analogy between luxury goods and luxury beliefs (as the luxury beliefs thesis requires). If an individual must choose between signaling to gain status while risking collective costs or refraining from signaling while also risking collective costs, signaling is the rational strategy.

This is a tragedy of the commons or a prisoner’s dilemma in which the stable strategy is to defect (i.e., to signal). Stated less technically, although the expression of a belief such as defund the police might hurt the lower classes if enough people embraced it, it is always in an individual’s self-interest to espouse it if it enhances his status.

Therefore, a signaling system in which people promote luxury beliefs to obtain status is not stable because it cannot distinguish cheaters from honest signalers. According to the luxury beliefs thesis, if Joe wants to obtain status, all he must do is assert that he is a champion of open borders and drug legalization. These beliefs are not difficult or costly to profess, so he should do so. This contrasts sharply with other (costly) displays of taste. If Joe claims to revere James Joyce or Thomas Pynchon, a skeptic might ask him, “Really? What was the name of Bloom’s son? Can you tell me about the Circe episode?” Or “What do you think about Tyrone Slothrop?”

There are at least two other major differences between luxury beliefs and luxury goods. First, luxury good are positional whereas luxury beliefs are not obviously so and second, luxury goods confer status among most (perhaps all) groups of people whereas luxury beliefs do not.

Positional goods derive their value from scarcity whether absolute or socially imposed. The value of a Porsche as a signal depends upon its scarcity. If everybody had a Porsche, its possession would become meaningless. It might still be a blast to drive, but it would no longer reliably communicate anything about a person’s underlying traits or social status. Therefore, a person who bought a Porsche would likely be crestfallen if he awoke one morning to discover that everybody in his community owned a Porsche. Because of this, those who own luxury goods generally do not attempt to spread those goods across society. In fact, elites have often imposed sumptuary laws that restricted specific groups from certain types of consumption to limit the availability of luxury goods.

Henderson is aware of this, writing, “Once a signal is adopted by the masses, the affluent abandon it,” but many of the proposed luxury beliefs do not follow this pattern. Advocates of defund the police or open borders or polyamory often work indefatigably to convert other people and seem earnestly thrilled when others adopt their beliefs. And the affluent have not abandoned many beliefs that might once have been considered luxury beliefs. Instead, those beliefs have become commonplaces.

Luxury goods are impressive to most people, even those who pretend not to care about such extravagances. Luxury beliefs, on the other hand, rankle and alienate many people. We can use something I will call the “date test” to examine this.

Suppose Joe arrives for a blind date in a Porsche. Will this increase or decrease his chances of securing the affections of his date? The answer is an unqualified increase. Now suppose that Joe says to his date, “I think the police are terrorists who harass and destroy the black body. They should be abolished!” Will this increase or decrease his chances? The answer is we have no idea because it depends almost entirely on the political views of his date. The same holds for professions of other luxury beliefs such as “I think the border should be eradicated” or “Whites are privileged and should feel guilty.”

Although luxury beliefs are probably not like luxury goods, i.e., they are not costly signals of social status, they may be signals of a different kind, namely, tribal signals or identifiers. Identifiers are pervasive, from gang colors to sports jerseys to NPR mugs and bumper stickers. They communicate one’s membership and commitment to a group or tribe. And just as shirts and bandanas can signal tribal allegiance, so can beliefs. If a person says, “I believe that every individual should be allowed to carry a concealed weapon,” we can reasonably predict that he is a Republican. Similarly, if a person says, “Policing is the greatest danger to black people,” we can reasonably predict that she is a Democrat. And if a person says, “I believe that Jesus Christ died for my sins,” we can reasonably predict that he is a Christian.

Identifiers share many qualities with luxury beliefs. They can become bizarre or extreme because their function is to distinguish one tribe from another and to elicit displays of loyalty from members. Advocating implausible or flamboyant beliefs can be an honest signal commitment to one’s own tribe since it often alienates those in other tribes (Credo quia absurdum est). And because they signal commitment, identifiers earn status within the ingroup. People respect and reward others who are loyal to the tribe. Furthermore, people are often motivated to proselytize such beliefs to increase the size of one’s tribe, which increases the tribe’s power and influence. This might explain why those who hold luxury beliefs often work assiduously to convert others. They want to expand their tribe and its influence.

If this is correct, the behavior of luxury beliefs should be similar to the behavior of the tribal beliefs of right-wing populists: MAGA hats, disdain for elites, opposition to abortion, immigration restrictionism, et cetera. We can apply the date test. If Joe goes on a blind date, will wearing a MAGA hat increase or decrease his chances of wooing his date? The answer depends almost entirely on his date’s political preferences. Similarly, if he espouses the belief that Trump won in 2020, the effect depends almost entirely on his date’s political preferences. This matches the effect of luxury beliefs. The most important variable when predicting the effect on a target is the target’s political ideology.

Thus luxury beliefs are a subset of a broader category of signals of tribal identity; and they only appear to be unique to progressive elites because those who discuss them often single out the tribal identity beliefs that are displayed by progressive elites and ignore those that are displayed by populists (or other tribes). However, if the tribal beliefs thesis is correct, the belief that we should defund the police is not functionally different from the belief that Donald Trump won the 2020 presidential election. They are both identifiers that signal one’s commitment to a coalition.

Evidence supports the tribal beliefs thesis. For example, Zach Goldberg, in a comprehensive piece for the Manhattan Institute found that support for depolicing policies is largely a function of tribal affiliation, though it is also related to wealth and education. As one would expect, Democrats are much more likely to support such policies than Republicans. Tribal affiliation is a more powerful predictor than affluence: “While greater education and (to a lesser extent) family income matter for the expression of pro-defunding and pro-depolicing attitudes, the data also suggest that ideological self-identification may be relatively more important.”

Even more important, Goldberg found that although living in relatively high-crime areas predicted less support for depolicing from black and Hispanic Democrats, the “data show no evidence that white Democrats are more likely to support defunding and depolicing because they tend to reside in low-crime areas.” Of course, the relation between class, education, ideology, and any specific belief or set of beliefs is complicated. On nuanced topics such as taxes and immigration and race, income, education, and political affiliation all predict attitudes and beliefs, though affiliation is generally the more powerful predictor. And more research is therefore needed to test competing hypotheses.

The luxury belief thesis is almost certainly incorrect as currently articulated in the literature. Nevertheless, the name “luxury beliefs” might be appropriate for a subset of beliefs that arise because elites are often isolated from and ignorant of the lives and behavioral propensities of ordinary people. In this, luxury beliefs are related to luxury, but they are not like luxury goods. To the extent that they signal, they signal tribal affiliation. And many of them are best understood as sincere but misguided attempts to understand or change the world while seeing it through a glass clouded by wealth and privilege.

Bo Winegard is the Executive Editor of Aporia.

We can only widen the Overton window with your financial support. Join our network by becoming a paid subscriber today:

We revolutionize society by fundamentally changing the gender roles in the past 60 years, telling girls that they are better boys. We see a sea change of women ending up in management. Disproportionately in government, NGOs, universities, schools, etc. These institutions become feminized and start to show the clear feminine pathologies of suppressing dissent, devaluing logic, ignoring reciprocity, increasing reputation warfare, hyper focus on empathy and feelings, and victim hood becomes currency.

And then we write an article like this trying to figure out what got us in this mess and not a single word about the mind boggling revolution we just witnessed in the last century.

I like your critique of the Luxury Beliefs concept....which has in any case become a bit of a cliche. My comment is about HOW these beliefs, contrary to all common-sense and observable evidence, have come to spread through Western civilisation like a virus:

Most people are intellectual sheep....always have been. In recent times though, two new things have happened 1) the ‘shepherds’ have been an up-itself Lefty intelligentsia that has colonised academia (without our ‘pluralist democracy’ even noticing the fact until recently) 2) an ever-expanding percentage of young people have been going through this academia sheep-dip. The rest is history.