Kings or Cleverness? How Revolutionary France Elevated Genius

WARNING: This article is replete with an incomprehensibly odd number of pretentious French subtitles.

Written by Matthew Archer.

It nearly always takes some stimulus to bring the genius on the scene. The hammer-stroke of Fate which throws one man to the ground suddenly strikes steel in another, and when the shell of everyday life is broken, the previously hidden kernel lies open before the eyes of the astonished world. The world then resists and does not want to believe [that it now beholds] a very different being.

— Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Mannheim (London, 1969), p.266.

How do you know if a revolution has been successful? We can find clues in the most mundane places; corners and alleyways, drawers and desks. Tucked away in the debris of daily life — the places we seldom give a second glance — are the answers to this question. Because a successful revolution doesn’t just change the big ticket items — the contours of existence, like say time itself — but any residue of the past which could imply a different possible future.

For example, whilst Jacobin zeal famously claimed the calendar, declaring Year I to have begun in 1789, the revolutionary spirit also changed the clothes ordinary people wore, the language they spoke, the books they read (if they could read), the plays they saw and the songs they sung. But the carcass of the Ancien Régime needed to be stripped of more than just its religious symbology, the Christian calendar being a prime example. Any vestige of royalty — of divine right — was a candidate for the memory hole. To my mind, there is no better example of this manic spree than the decks of revolutionary playing cards which began to circulate a few years after the Storming of the Bastille.

Génie ou Rois?

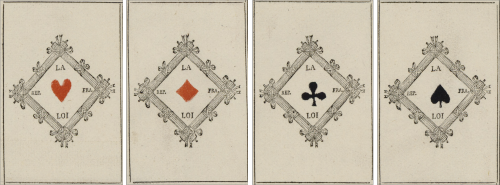

In one deck the Aces — the highest cards in the deck — were replaced with La Loi (the law), under which everything else was subject. But then it became interesting.

We find the Kings (rois) — the second highest cards — replaced with spirits or geniuses (La Génie) of War, Peace, Art, and Commerce.

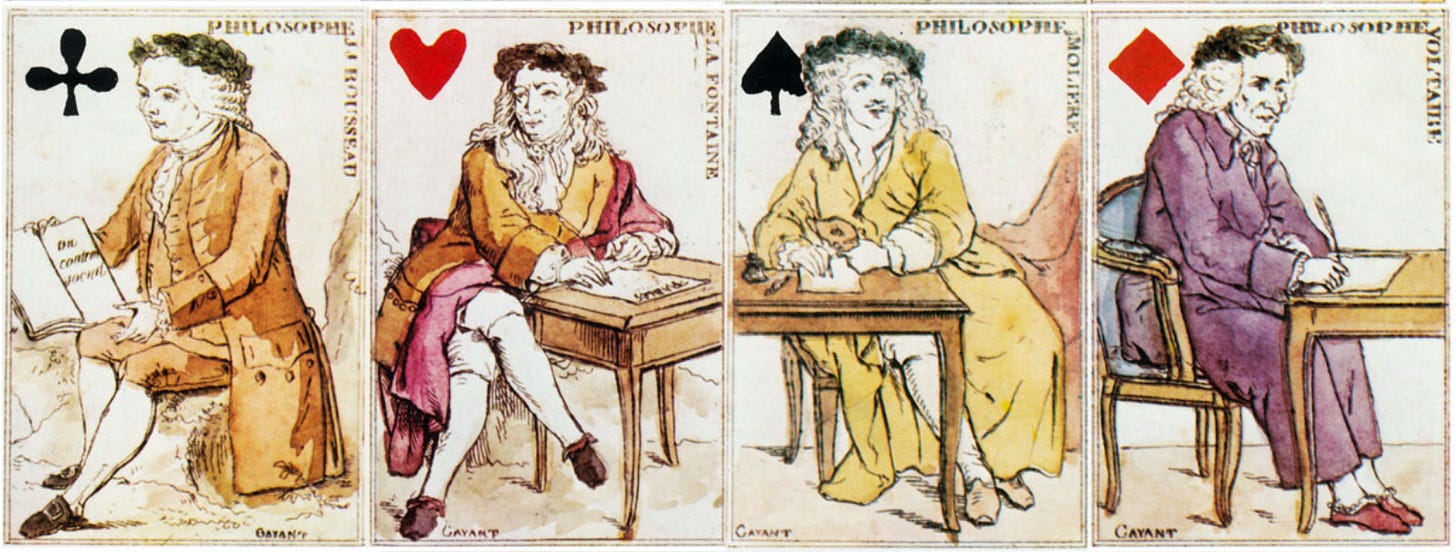

In another deck printed in 1793 by the publisher Gayant, we find the kings replaced by philosophers: Voltaire, La Fontaine, Molière and Rousseau, to be precise.

As Professor Darrin McMahon writes in his book, Divine Fury: A History of Genius, this was ‘wonderfully symbolic of the genius’s newly exalted status’. He continues:

“Genius” and the “genius of France” graced revolutionary coins, just as the genius of the emperors had once sealed the specie of Rome. Symbolically, the genius was usurping the place of sovereigns and claiming the right of kings.

Fête du Génie

Of course, there were greater aspirations beyond playing cards and coins. When the Christian calendar was abandoned, an actor and poet by the name of Fabre d'Eglantine renamed the months in a quintessentially French fashion (the first he called vendémiaire because it was the wine harvest season). However, he also proposed a fête du génie (a festival of genius), a day at the end of the year to recognise those who France was most in debt to. Upon submitting his proposal to the National Convention, Fabre declared that the holiday would honour the:

[…] “most precious and lofty attribute of humanity—intelligence—which sets us apart from the rest of creation.” The “greatest conceptions, and those most useful to the nation,” would be celebrated on this day, along with “all that relates to invention or the creative operations of the human mind,” whether in “the arts, sciences, trades, or in legislative, philosophic, or moral matters.”

Translation by Darrin M. McMahon

It remains unclear whether the festival was ever celebrated amidst the chaos.

Les Droits du Génie

The elevation of the genius in revolutionary France is best exemplified in a statement by the political revolutionary Joseph Lakanal. Whilst advocating for legislation to protect the intellectual property of authors, Lakanal proclaimed “the declaration of the rights of genius”. Professor Carla Hesse writes:

With the "declaration of the rights of genius," the power to determine the meaning and fate of ideas devolved from the state, the family, and the corporate publishers to individual authors and to the public at large. The ideal of an enlightened republic was embodied in more than just the "rights of genius"; it lay also in the notion of democratic access to a common cultural inheritance, preserved in the public domain.

What The French Gave Us

McMahon summarises what the French Revolution did for the genius:

By linking geniuses emphatically to politics and political change, the revolutionaries highlighted the capacity of extraordinary individuals not just to understand the world, but to change it. Only with the Revolution could a myth of revolutionary genius emerge, and with the propagation of that myth was born a possibility, still fledgling, but soon to be fulfilled: that genius might be used as the basis of political power, celebrated not only in death but in life, employed to justify an extraordinary privilege and license. The very possibility raised a question: What was the place of the genius in a free nation? To a regime that had declared liberty, equality, and fraternity as its founding ideals, it was not an idle concern.

Now, more than 200 years later, it still seems as though the question of the genius’ place in a free nation remains unresolved. Whilst it’s true that famous faces still adorn bank notes and specie, the myth of the revolutionary genius seems to have passed. As for the idea that genius might be used as the basis for political power? Never has the phrase “wishful thinking” been more appropriate. How many readers could even name one or more of this year’s Nobel Prize winners?

Perhaps we are in a genius famine. If so, we may have to sustain ourselves with symbology. Though that doesn’t seem likely either. In 2024, the European Central Bank will decide on a new design of the (currently soulless) euro banknotes. They are to hold focus groups with the aim of making the notes ‘more relatable to Europeans of all ages and backgrounds.’ But the genius, of course, is the opposite of relatable. And that is precisely what should be celebrated.

Matthew Archer is the Editor-in-Chief of Aporia Magazine.