Is spanking always harmful to children?

If advice about parental discipline is getting better, why are children more anxious and depressed than in previous generations?

Written by Robert E. Larzelere.

Is spanking always harmful to children – regardless of how it’s used and what it’s used for? Media stories about parental discipline seem to say so. But is this true? And if advice about parental discipline is getting better, why are children more anxious and depressed than in previous generations?

In 2018, the American Psychological Association’s Task Force on Physical Punishment of Children recommended a resolution opposing all forms of physical punishment. Although the Task Force cited five meta-analyses, they relied heavily on a paper that reported unadjusted correlations. They also ignored two stronger meta-analyses that concluded the harmful effects of physical punishment are either trivial or limited to cases of severe and predominant use.

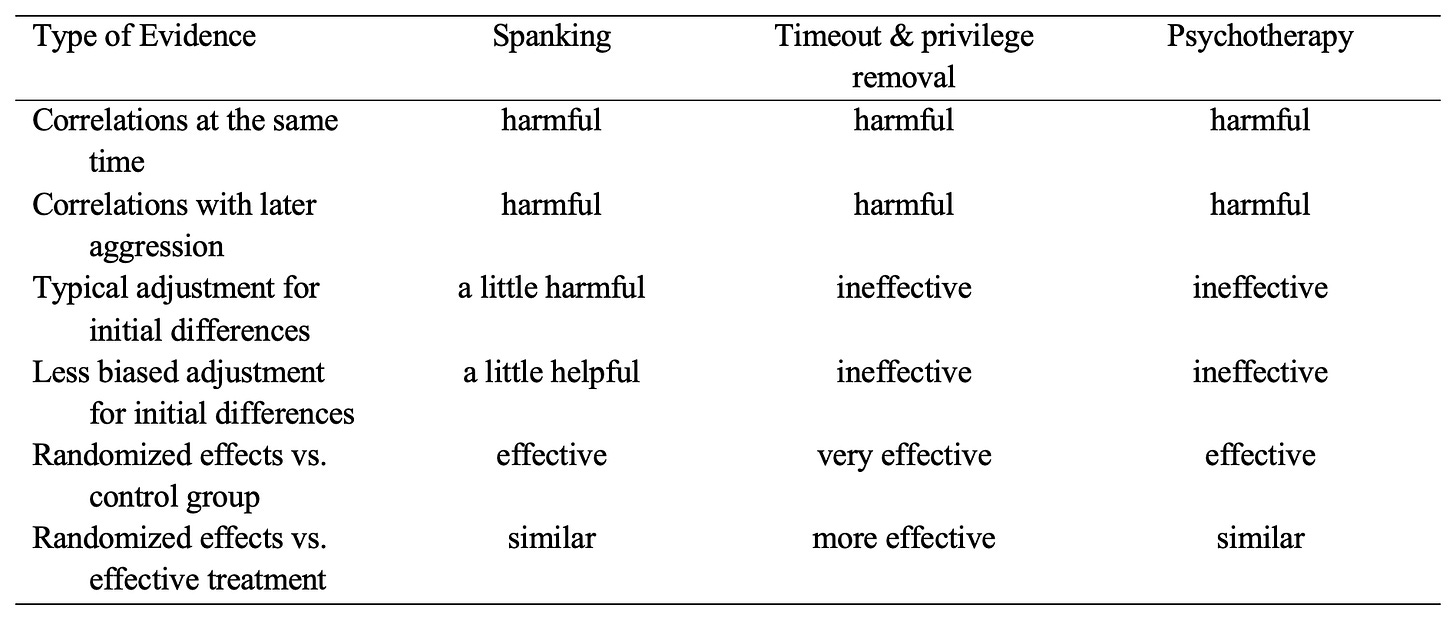

In a recent book chapter, three colleagues and I looked in detail at the relationship between spanking and children’s antisocial aggression. We also looked at two other corrective actions: timeout & privilege removal and psychotherapy. We assembled the table below, which summarizes what different types of evidence say about each corrective action: is it harmful or helpful in reducing children’s antisocial aggression?

Looking at the first two rows, correlational studies suggest that all three corrective actions are harmful in the sense that they’re associated with more antisocial aggression on the part of children. (These are the studies on which the APA’s Task Force so heavily relied.) So children that are spanked tend to be more aggressive. But of course, this doesn’t mean the spanking is what caused them to be aggressive.

Turning to the middle two rows, studies that try to adjust for initial differences have much more mixed findings. The corrective actions appear to be neither harmful nor helpful, or in the case of spanking slightly harmful or slightly helpful, depending on the type of adjustment.

Now look at the final two rows. Randomized studies – by far the strongest form of evidence – suggest that all three corrective actions are at least somewhat effective. It should be noted that the randomized studies of spanking used spanking to enforce compliance with time-out, and only included children who were clinically referred for oppositional behavior problems. So one can’t infer that spanking is always effective. Nonetheless there do appear to be circumstances when it is effective, especially for the most defiant children.

It turns out that the evidence against spanking is surprisingly similar to the evidence against non-physical punishments and psychotherapy. How then do researchers end up concluding that spanking and other forms of parental punishments are harmful, while certain other corrective actions are helpful? They do so by emphasizing the part of the outcome pattern that fits their preferred conclusion.

If they support the corrective action (e.g., psychotherapy, Ritalin) they insist on randomized studies of the most appropriate versions of those treatments. But if they oppose it (e.g., spanking, timeout) they consider correlational evidence sufficient – despite the well-known dictum “correlation is not causation.” In addition, they cite studies that do not test the most appropriate use of spanking in the most appropriate disciplinary situations (i.e., to enforce compliance with time-out).

This biased approach explains why anti-spanking researchers cannot find any alternative that reliably reduces antisocial aggression.

In their only known studies testing other disciplinary actions, anti-spanking researchers examined 11 such actions via 76 statistical tests, but found no improvements in antisocial aggression or other outcomes. They thus oppose not only spanking, but also timeout and privilege removal – despite the documented effectiveness of both actions.

In one recent study by anti-spanking researchers, the alternative action of verbal explanations did prove beneficial. Yet the study failed to distinguish “teaching children the right behavior” from “addressing a behavior problem.” Of course, parents should use explanations and other positive actions as much as possible. However, those who refrain from spanking need effective alternatives when children are defiant, not only when they are ready to listen.

What does appropriate spanking look like? Parents of young defiant children were trained to use two swats to a child’s bottom to enforce cooperation with timeout. The purpose was to teach children to cooperate with timeout, and the back-up spanking was subsequently phased out. Its effectiveness was documented in four randomized studies of clinically defiant 2- to 6-year-olds. For example, one such study compared the back-up spanking with letting the child decide how long to stay in timeout. Compliance to maternal commands improved much more with the back-up spanking (from 23% to 78%) than with the child-determined duration (from 23% to 44%).

The other three randomized studies found only one alternative to be as effective as the spank back-up – a brief isolation period in another room. And in fact, the latest review of timeout variations confirmed that spanking and the brief isolation period were the most effective enforcements for timeout, even though both were opposed by professional societies.

Can you imagine professional societies opposing the two most effective medications for Covid-19? That is exactly what has happened with respect to actions for treating oppositional behaviour problems in young children.

A recent Harvard study found that psychotherapies for oppositional defiance are half as effective now as they were 30 to 50 years ago when spanking was the preferred enforcement for timeout. The only review that compared spanking with other disciplinary actions found that back-up spanking led to less aggression or defiance than 10 out of 13 alternatives.

Back-up spanking is effective because it is: non-abusive (not out-of-control due to anger); used specifically for defiance after milder tactics have already been tried; and used specifically with two- to six-year-olds. There is no evidence against this type of spanking. And children eventually learn to comply with the milder tactics, allowing spanking to be phased out. Indeed, the only study of phased-out spanking found that it was associated with better academic performance and more prosocial behavior.

Robert E. Larzelere is a professor in the department of Human Development & Family Science at Oklahoma State University. He can be reached via email.

“Can you imagine professional societies opposing the two most effective medications for Covid-19? That is exactly what has happened with respect to actions for treating oppositional behaviour problems in young children.”

Why yes, yes I can.

Simply put, I think spanking is mostly not harmful. Context is everything though. It is certainly not a zero sum issue.

I was spanked occasionally by my parents from the ages of about 4-9..and I am grateful for it. It’s complex because each family is different.