How Taboos Affect Science

A new study sheds light on taboos in science, confirming that race and IQ is the most taboo subject of all.

Written by Emil O. W. Kirkegaard.

Aporia has published a lot about taboos in science – such taboos seem obvious and powerful to those who’ve flouted them. Yet hard data on the topic are scarce. The publication of a new and important study by Cory Clark and colleagues, Taboos and Self-Censorship Among U.S. Psychology Professors, changes this and confirms what many already suspected: taboos are common in academia. However, it also complicates the story, suggesting that most scholars actually oppose discouraging research on the most incendiary of topics, namely race and IQ.

The authors began by interviewing 41 researchers in psychology to get an idea of which topics are most taboo. Using the researchers’ answers as a guide, they condensed the topics to a set of 10 statements:

The tendency to engage in sexually coercive behavior likely evolved because it conferred some evolutionary advantages on men who engaged in such behavior.

Gender biases are not the most important drivers of the under-representation of women in STEM fields.

Academia discriminates against Black people (e.g., in hiring, promotion, grants, invitations to participate in colloquia/symposia).

Biological sex is binary for the vast majority of people.

The social sciences (in the United States) discriminate against conservatives (e.g., in hiring, promotion, grants, invitations to participate in colloquia/symposia).

Racial biases are not the most important drivers of higher crime rates among Black Americans relative to White Americans.

Men and women have different psychological characteristics because of evolution.

Genetic differences explain non-trivial (10% or more) variance in race differences in intelligence test scores.

Transgender identity is sometimes the product of social influence.

Demographic diversity (race, gender) in the workplace often leads to worse performance.

Based on these statements, they surveyed 470 psychology professors from highly regarded schools and universities in the United States. Each subject was presented with a scientific statement and asked these questions:

How confident are you in the truth or falsity of this statement? (responses ranged from “100% confident it is false” to “100% confident it is true”)

If the topic came up in a professional setting—for example, at a conference—how reluctant would you feel about sharing your beliefs on this topic openly?” (responses ranged from not at all reluctant to extremely reluctant),

Should scholars be discouraged from testing the veracity of this statement?” (responses ranged from no discouragement to very strong discouragement)

In short, they measured the scientists’ belief in the statements, their reluctance to share their views, and how much they supported discouraging research into the question, whether through overt censorship or some other means. I have plotted their main results below.

Each dot shows the average rating of a given question, the color shows the metric, and the error bars show the mean + standard deviation, so as to measure disagreement or diversity of views among the professors. Genetic contributions to IQ differences was the most discouraged research question, while the binary-ness of sex was the most believed statement. Contrary to what you typically hear in the media and from some scientists, there was no scientific consensus for any topic: all average ratings fall between 21 (Demographic diversity and performance) and 66 (Binary biological sex), and the standard deviations are wide. Experts are divided on most of the topics, just as the general population is. Encouragingly, levels of support for discouragement were fairly low: not even genetic contributions to IQ differences reaches an average of 25 (out of 100).

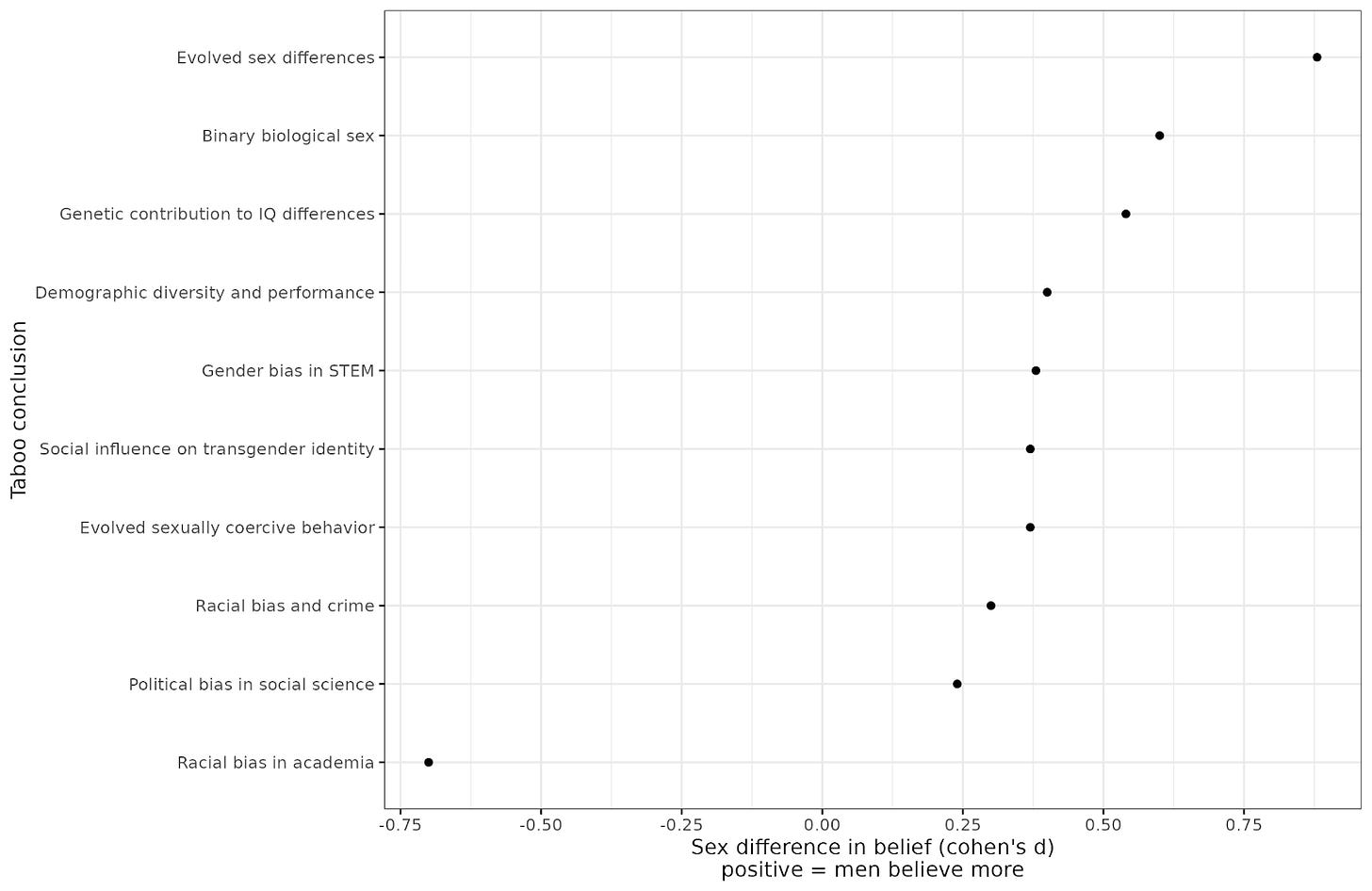

In terms of the origins of censorship, female professors believed every inegalitarian or non-woke conclusion less than men, as shown below.

Consequently, they were also more in favor of discouraging the relevant research. Men were also more self-censoring than women. One might be tempted to explain this in terms of the less conservative views of women (the women were also younger and younger professors hold more left-wing views), but this difference was still present when conservatism was statistically controlled (i.e., held constant). It isn’t possible to investigate alternative models because, as the authors say, “To encourage honest responding, we assured participants that all demographic variables and open-ended responses would be removed from the data file before we shared it publicly (to ensure anonymity).” Ironically, this is yet another example of taboos negatively affecting science.

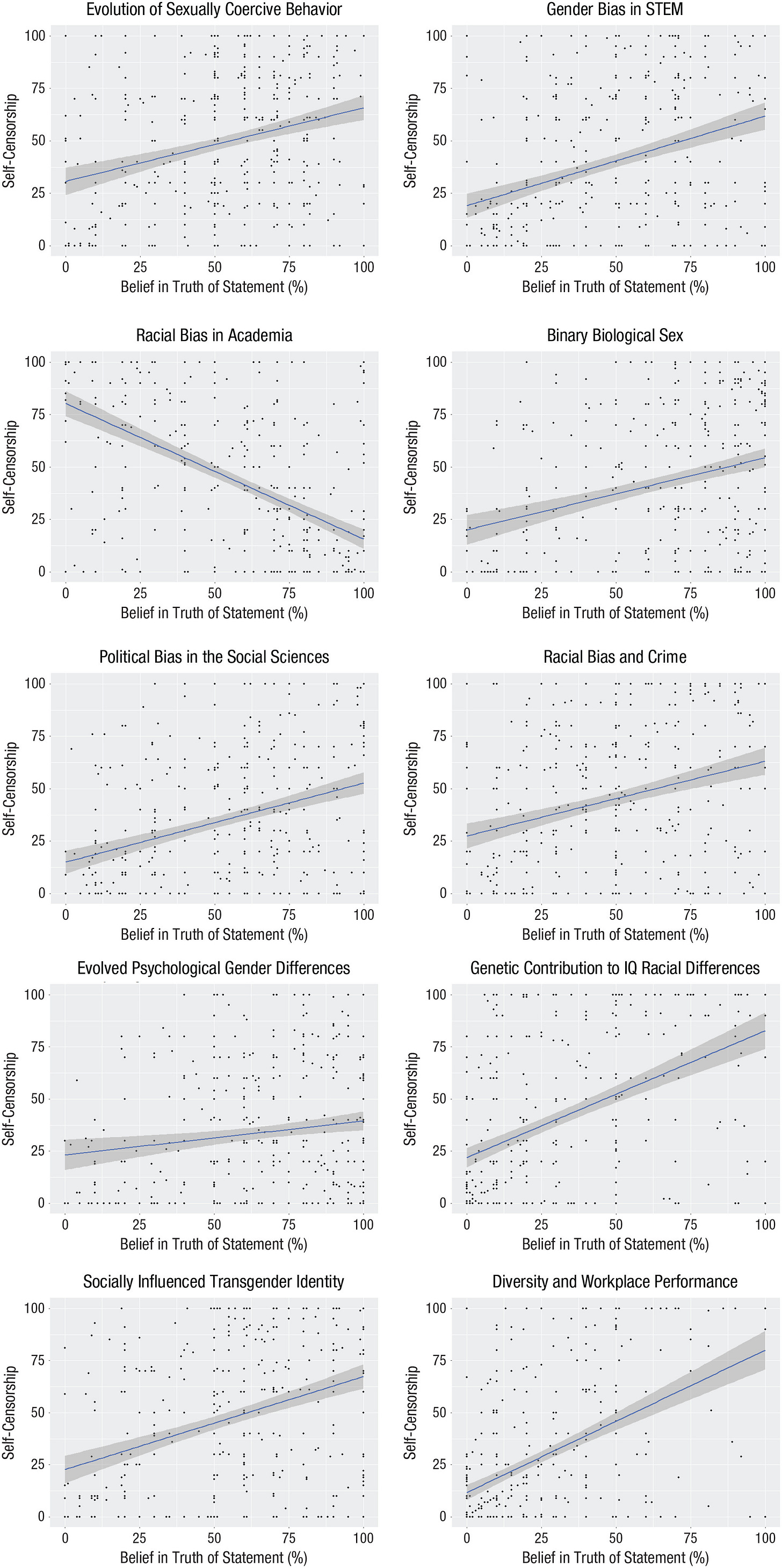

The upshot of these findings is that scholars who question prominent views in society cannot openly research them without risking getting censored, harassed or fired. Because of the structure of academia and the disproportionate influence of activists, the scientific community is effectively unable to research these topics. This is clear when we look at the association between degree of self-censorship and belief in each of the conclusions. In each case, those who believe the taboo conclusion are more likely to self-censor.

The relationship was particularly strong for genetic contributions to IQ gaps, and for diversity and workplace performance. Many professors with even moderate views on the questions said they self-censor.

An optimist may note that most professors were opposed to firing researchers who pursued taboo topics. This might be surprising since news about cancelled academics is fairly common. It suggests that such actions are either instigated from outside the university or by a small minority of radical professors.

There are various conclusions one could draw from this study. The first and most important is that contrary to some widely implausible claims, there are many taboos in science. The second is that taboos, and the punishments for breaking them, are important enough that self-censorship is common. This wastes resources and distorts science. The duty of researchers is to discover the truth, not to surrender to popular dogmas. Society pays the price since self-censorship slows down the scientific process. And policies that are based on erroneous premises may have disastrous consequences. For this reason, the taboo problem must be confronted.

The demographics of censorship supporters will be no surprise to those who’ve read George Orwell: “It was always the women, and above all the young ones, who were the most bigoted adherents of the Party, the swallowers of slogans, the amateur spies and nosers−out of unorthodoxy.” (in 1984). Being young, female, and having left-wing politics predict censorship of the studied topics, and seem to have independent effects. This is not too surprising because 9 of the 10 questions concern taboo conclusions that go against dominant left-wing narratives. One might even be tempted to ask the unwelcome question: why do we have so many young women in science if their values go against the scientific ethics of open debate?

Leaving that question aside, it is worth noting that the current study indirectly replicated a recent study of our own. In our study, we asked 500 Americans to rate the tabooness of 33 scientific questions.

Our study also found that the most taboo topic concerned intelligence differences between groups. Interestingly, this was even perceived to be more taboo than otherwise eyebrow-raising questions concerning the harms of incest, pedophilia, the mental illness of transsexuals, biological causes of homosexuality, and Jewish power. If Nathan Cofnas is right that the ascent of extreme forms of leftism or quasi-communist wokeness in recent years is partially caused by the collective denial of naturally caused or otherwise fair race differences in intelligence, it doesn’t bode well for the future of the United States and other Western countries.

I don’t want to end on a pessimistic note, as I’m fundamentally an optimist. The advent of open science practices, in particular open datasets, has facilitated the reemergence of non-institutionized science. Hobbyists reading papers at home and academics posting under pseudonyms now have the ability to participate in science using data others have collected. Really, this should have been the case all along because the public was paying the bill for the research.

Before the internet age, it wasn’t easy to share your data with others, but with the growth of services like Open Science Foundation’s free to use repositories, and other similar services, it has become easy to share data. Institutional changes – whether journal or university policies – that force authors to post their datasets publicly has led to this revitalization of citizen science. And while a few leftist academics like Kathryn Paige Harden have voiced their concerns over their loss of data privilege and thus control, this has been a boon for open science.

Taboos on certain topics are a constant feature of human civilizations of past and present. There were good reasons why dissident intellectuals in religious, political, and philosophical movements wrote under pseudonyms in fear of reprisals from the powers that be – think of the early Protestant movement criticizing Catholic abuses of power, of the American founding fathers criticizing English dominion, or the enlightenment philosophers probing at the foundations of society. While some dubious characters spend their lives trying to reveal the identities of pseudonymous writers (e.g. the recent case of Lom3z, doxxed by an Antifa activist publishing in The Guardian) writing pseudonymously or even anonymously is a time-tested approach to defying dogmas. Let’s hope that today’s shattered taboos are tomorrow’s obvious truths.

Emil O. W. Kirkegaard is a social geneticist. You can follow his work on Twitter/X and Substack.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

To chat with fellow Aporia readers and attend meet-ups, join our Telegram. You can also follow us on Twitter.

There are still a few reasons to be proud to be a man.

"The demographics of censorship supporters will be no surprise to those who've read George Orwell: "It was always the women, and above all the young ones, who were the most bigoted adherents of the Party, the swallowers of slogans, the amateur spies and nosers-out of unorthodoxy."

Very impressive! Any chance you could write about the very interesting phenomenon where many/most scientists, and definitely science's fan base, are oblivious if not worse to what you've pointed out here? It's a very big problem.