Housebuilding or immigration?

A scarcity of homes not only leaves renters and mortgage-holders with less disposable income, but contributes to a host of social ills.

Written by Noah Carl.

The cost of housing is widely considered one of the UK’s biggest economic problems – if not the biggest. According to the housing theory of everything, a scarcity of homes not only leaves renters and mortgage-holders with less disposable income, but contributes to a host of social ills, including obesity, inequality and sub-replacement fertility.

In a recent article, the FT’s John Burn-Murdoch argued that housing has become particularly scarce in English-speaking countries like Britain, where prices have risen more steeply since the global financial crisis. He presented the following chart, which shows the divergence between those countries and advanced European economies.

To further investigate the trends in Britain, I obtained the dataset Burn-Murdoch used for his analysis, namely James Gleeson’s PublicHouse dataset. All the numbers for Britain come from the UK government, and are publicly available online (see the source publications and source links that Gleeson has helpfully provided).

I first recreated Burn-Murdoch’s left-hand chart above, limiting the sample to Britain and the three largest European economies. The pattern is clear: while the number of dwellings per 1,000 people has increased more-or-less continuously in France, Germany and Italy, it has flattened out in Britain since around 2000.

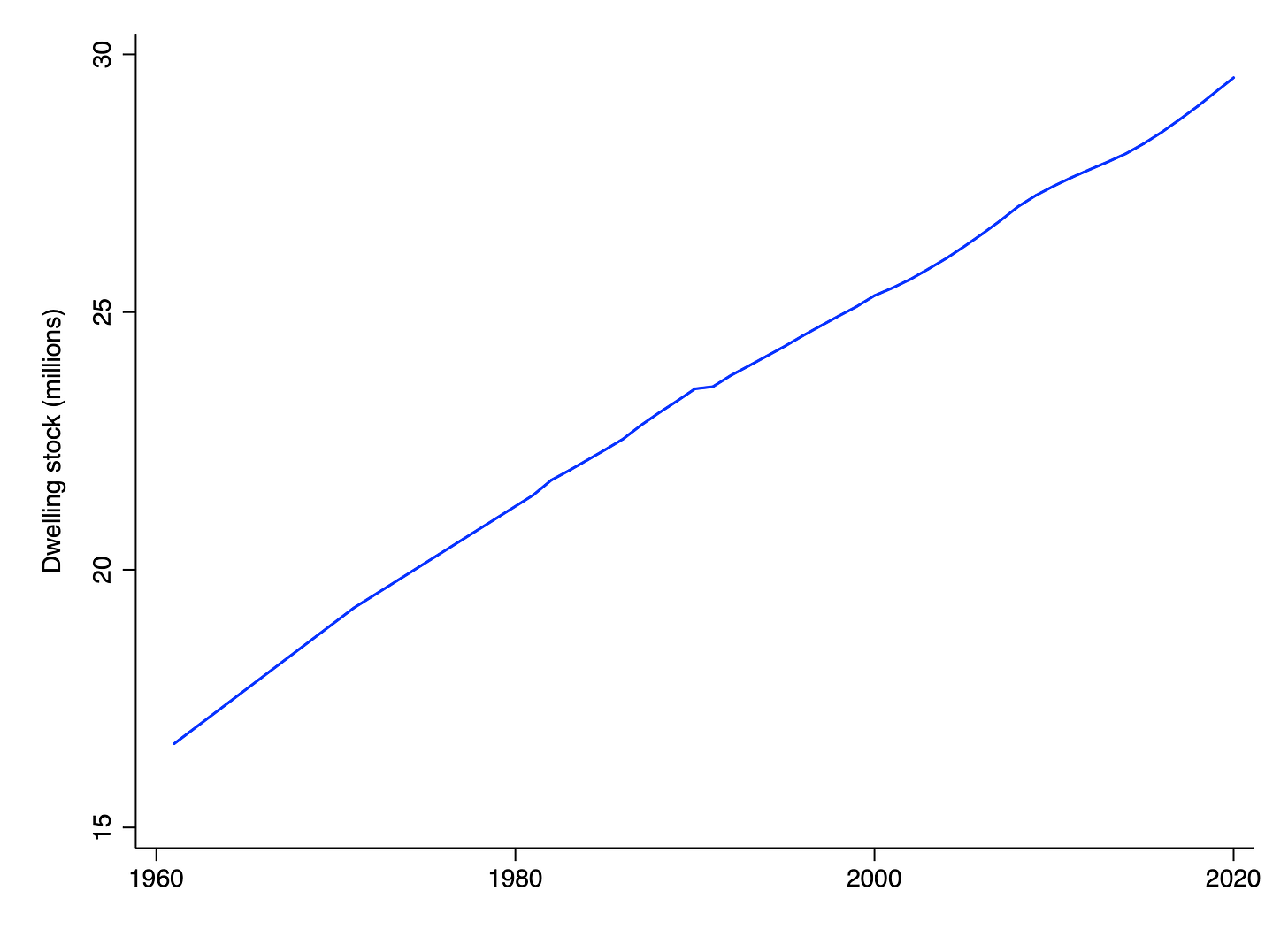

What explains the trend in Britain? You might assume that the dwelling stock was increasing at a steady clip until around 2000 when the number of new dwellings suddenly began to fall. We can check this by simply plotting the total number of dwellings over time:

As you can see, that’s not what happened. The dwelling stock has been increasing at pretty much the same rate since the early 1960s; there’s no obvious bend around 2000. So what happened? We have to look at the other part of the fraction – the total number of people.

As you can see, population began increasing at a much higher rate around 2000 – and that is what explains the flattening out of the number of dwellings per 1,000 people.

From 1961 to 1999, the dwelling stock increased by 218,000 per year. Then from 2000 to 2020, it increased by 208,000 per year – which is only slightly lower. Population is a different story. From 1961 to 1999, it increased by 117,000 per year. Then from 2000 to 2020, it increased by 439,000 per year – which is more than three times higher.

So rather than increasing the dwelling stock too slowly to keep up with population growth, it would be more accurate to say we’re increasing the population too fast to keep up with growth in the dwelling stock.

Of course, a major contributor to population growth since 2000 has been immigration. Net migration averaged around 200,000 per year, equating to 4 million extra people over the whole time period. (Since fertility has been below replacement level since the early 1990s, the other contributors were population momentum and rising life expectancy.)

Using the PublicHouse dataset, we can work out that if population had increased at the same rate from 2000 to 2020 as it increased from 1961 to 1999, the number of dwellings per 1,000 people in 2020 would be 485 instead of 440. And Britain would have closed 60% of the gap with Germany.

An important caveat is that demand for housing is influenced more by the number of households than by the number of people per se. There can be more or fewer households for a given number of people, depending on social arrangements (e.g., average family size). However, social arrangements have not shifted dramatically in the last few decades.

This is far from the first time someone has drawn attention to immigration’s role in the housing crisis. For example, the thinktank Migration Watch maintains that “immigration is the largest component of rising demand” for housing. But it bears repeating.

The problem of dwellings being scarce can just as well be seen as the problem of people being too abundant. And when we compare Britain to the other large European economies, its divergence is explained almost entirely by a rise in the number of new people, rather than by a fall in the number of new dwellings.

I therefore can’t understand why someone like Sam Bowman (whose recent article on Britain’s economic troubles I largely agreed with) can describe more housebuilding as “the biggest single fix for the UK economy”, while dismissing immigration control as a “preoccupation of the elite”.

Note that supporting high-skilled immigration on economic grounds is perfectly reasonable. I just don’t understand how increasing the number of dwellings can be “the biggest single fix” if reducing the number of people that need to live in them isn’t even worth considering.

Noah Carl is an Editor at Aporia Magazine.

Please consider supporting our work with a paid subscription and follow us on Twitter.

I have thought this the case for quite some time but assumed I had misunderstood something basic since I never heard anyone mention immigration in connection with the housing crisis. This article confirms that I'm not going mad and I now have the figures to prove it!

I don't have any solutions but I do get sick of the ubiquitous, unreflective journalistic meme about Britain's failure to build enough new homes. If we're talking fundamentals......Britain does not have a 'Housing Crisis'; it has a family-formation, single-parenthood crisis.

Yes it's too late now to row back but at least let's call a spade a spade. https://grahamcunningham.substack.com/