Written by Peter Frost.

Whites made up 96% of euthanized Canadians in 2024. I couldn’t believe it. Yes, euthanasia mostly involves seniors, and older Canadians are whiter. But the 65+ age bracket was only 86% white at the last census in 2021 and is less so today (Statistics Canada, 2025).

I looked up the latest report on Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) in Canada. Here is the relevant paragraph:

A total of 15,927 of the 16,499 people who received MAID in 2024 responded to this question, the vast majority of whom (95.6%) identified as Caucasian (White). For context on how this compares to the overall population of Canada, approximately 70% of people in Canada identified as Caucasian in the most recent Census. (Health Canada, 2025, p. 32)

Why are Euro-Canadians “over-euthanized”? Let me answer by examining how their risk of euthanasia varies by medical justification and place of death. Why is the risk higher when natural death isn’t near? Why is it higher when the recipient lives in an institution, rather than at home? And why is it higher in certain provinces than in others?

When natural death is near versus when it isn’t

A request for MAID follows one of two tracks: Track 1 for recipients whose death is “reasonably foreseeable”; and Track 2 for those whose death is not “reasonably foreseeable.” In 2024, whites were 94.8% of Track 1 deaths and 97.4% of Track 2 deaths (Health Canada, 2025, p. 32). Track 2 deaths also had a lower median age, 75.9, even though younger seniors tend to be less white.

Euro-Canadians are thus over-euthanized for reasons that run counter to the natural processes of aging and illness — the former preconditions for MAID. Whiteness matters less when the decision is to hasten a natural death. It seems to matter more when the decision is to hasten death independently of medical justification.

So who is making whiteness a risk factor: those who request euthanasia, or those who approve the request?

Are whites more likely to request MAID? Let’s begin with the requesters. Euro-Canadians are more individualistic than other Canadians. They are more likely to live on their own after retirement with neither a spouse nor children to help. So they may be less motivated to continue living, regardless of their medical condition.

Euro-Canadians may also feel alienated in a country that scarcely resembles the one of their youth. This factor, like the preceding one, would matter more in MAID requests when death isn’t near.

Are their requests more readily approved? A MAID request must be approved by two medical professionals. Approval, once granted, is not reviewed by anyone else. Medical professionals can have personal biases, like anyone, and such biases are less constrained if MAID approval isn’t reviewed or requires no medical evidence. Personal biases may include resentment against Euro-Canadians for past or present discrimination or for banal reasons, like a dispute with a neighbor.

For that matter, a personal bias might harm Euro-Canadians without specifically targeting them. It could simply be a more favorable attitude toward one’s in-group. For instance, a physician may be more willing to sit down and discuss alternatives to MAID if the requester comes from the same culture, shares the same religion and is perhaps a relative. This is less likely if the two people come from different backgrounds. The request will then be more readily approved — not out of animosity but because the physician has less time or ability to talk the requester out of it.

If both are Euro-Canadians, the physician may insist on treating all requesters equally — or even overcompensate by showing more concern for those of a different culture. This desire to talk the requester out of it can vary from one situation to another and from one province to another, as we will see. It is especially critical when time is limited and the physician must choose between talking with the current patient or moving on to the next one.

Keep in mind that primary care physicians see about a hundred patients a week and are always under pressure to keep their caseload at a manageable level. If the desire to dissuade isn’t strong enough, approval will inevitably be granted for reasons of convenience.

Trudo Lemmens (2025) documents the case of a man who, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, feared he would end up in long-term care. He signed a waiver of final consent for MAID that would take effect in three and a half years, subject to certain preconditions: difficulty eating or swallowing, bodily tremors, inability to verbally communicate, etc. Less than a year later, he was hospitalized after a fall and became delirious. During “a period of cognitive improvement,” he was deemed capable of consent and given a lethal injection. His previous wishes, as stated in his initial consent, were ignored.

The system invites abuse because a wrongly euthanized person cannot lodge a complaint. The complaint must come from a surviving family member, and this is where the individualism of Euro-Canadians may play a role. If a physician has a heavy caseload, who is easier to “unload”? Someone with ties to many relatives or someone with none?

Death in an institution versus death at home

Table C.5 of the above report provides a breakdown of MAID deaths by ethnicity and province or territory (Health Canada, 2025, p. 80). We previously saw a national total of 15,226 deaths among whites or “Caucasians” (Health Canada, 2025, p. 32). Yet if we add up the provincial and territorial subtotals, we now get a total of 14,215 deaths among whites. The second total is 6.6% lower.

It isn’t unusual for death statistics to show a discrepancy between the national total and the combined regional total. The discrepancy arises because the form filler is unsure what to write for the deceased’s address and leaves the field blank. Yes, the province of death can be inferred from other fields, and even from the form itself, but such inference requires manual intervention when the forms are processed.

While the address is seldom left blank on a death certificate filled out at the deceased’s home, either a private residence or a retirement home, it often is when the certificate is filled out at an institution, such as a hospice, hospital, palliative care facility, residential care facility, correctional facility or shelter.1

Institutions account for 10.5% of Track 1 deaths and 18.4% of Track 2 deaths (Health Canada, 2025, p. 55). If missing addresses explain the discrepancy between the national total and the combined provincial total, we can infer that the address field was left blank in about half of institutional MAID deaths.

This discrepancy reveals another. Whites are 95.6% of the national total but only 86.2% of the combined provincial/territorial total. If the second total does exclude many institutional deaths, we can infer that Euro-Canadians are more at risk of euthanasia in an institutional setting.

A gap of 9.4 percentage points separates the white share of institutional MAID deaths from the white share of at-home MAID deaths — a gap almost equal to the one between the white share of MAID deaths and the white share of Canada’s senior population (i.e., 9.6 percentage points). The higher risk of euthanasia for whites seems to be confined almost entirely to those institutional deaths, where the form filler did not bother to fill in the address field. Are the addresses of Euro-Canadians harder to look up?

We will return to this point. For now, let’s use the provincial totals while remembering that they understate the white over-representation in MAID deaths. This understatement should, if anything, reduce the differences between provinces in white over-representation, making them seem smaller than they really are.

Whiter provinces versus less white ones

Canada’s ten provinces differ linguistically, politically and ethnically. Quebec stands out not only as an overwhelmingly French-speaking province but also as a highly secular one where public policy is no longer shaped by the Catholic church or even Christianity in general.

The provinces also differ in ethnic makeup. Canada’s population was about 97% of European descent in 1961, but this percentage has fallen since the shift to global immigration in the 1960s, particularly in British Columbia and Ontario — where most non-European immigrants have settled. In contrast, Quebec and the Atlantic provinces have received much less immigration and are now the whitest areas of Canada.

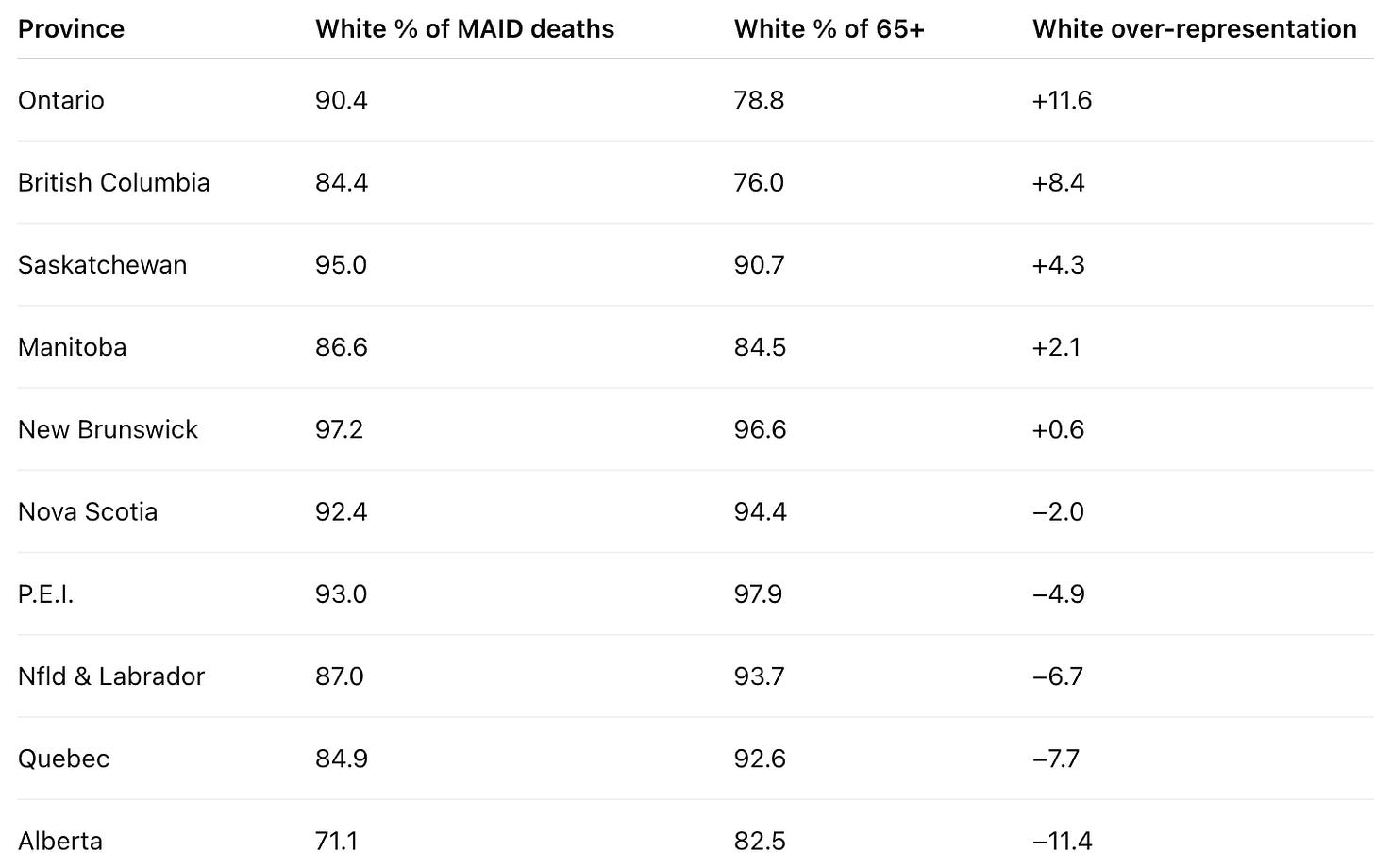

Do these provincial differences have any bearing on MAID deaths? Are whites more over-represented in some provinces than in others? We can answer this question by comparing the white percentage of MAID deaths in each province with the white percentage of the senior population. The following table shows how much whites are over-euthanized by province:

MAID deaths were not whiter than the 65+ bracket in the Atlantic provinces, Quebec and Alberta. But they were very much so in Ontario, British Columbia and Saskatchewan.

The same pattern appears if we compare the white share of MAID deaths with the white share of the general population. Euro-Canadians are more likely to be euthanized in those provinces where they are proportionately fewer — except for Alberta. Its demographics are like Ontario’s, yet the two are poles apart in terms of white over-representation in MAID deaths.

As with the Track 1/Track 2 differences, these interprovincial differences may be due either to the requester or to the physician approving the request.

Are whites less likely to request MAID in whiter provinces? Euro-Canadian culture may be less individualistic in whiter provinces. Poorer provinces attract fewer immigrants and thus tend to be whiter, more traditional and more culturally resistant to market forces. Their residents prefer to stay near relatives in a stable community, rather than move elsewhere for a better-paying job. Québécois also wish to preserve the French language and culture even if the result is slower growth.

In such provinces, older Euro-Canadians receive more emotional and material support from other family members and the community at large. These factors may explain why Euro-Canadians are less likely to seek euthanasia in some provinces than in others.

Again, Alberta is an exception. Its demographics are like Ontario’s: 66.5% white versus 62.9% white in 2021. It is also one of the provinces with the fewest locally born residents — only 52%. Yet it is also the province where whites are the least likely to be euthanized compared to other groups. Are they more religious? Actually, self-identified Christians are less common in Alberta than in the country as a whole, and other measures portray the province as average in terms of religiosity (Cornelissen, 2021).

Quebec is another exception. It is the province where whites are the second-least likely to be euthanized compared to other groups. It is also the least religious province by any measure, with the lowest percentage of people participating in group religious activities at least once a month (Cornelissen, 2021).2

Something else seems to explain the Alberta and Quebec exceptions. Both may simply be less “woke.” They have not gone as far as other provinces in normalizing anti-white thinking, discourse and behavior. We will return to this point.

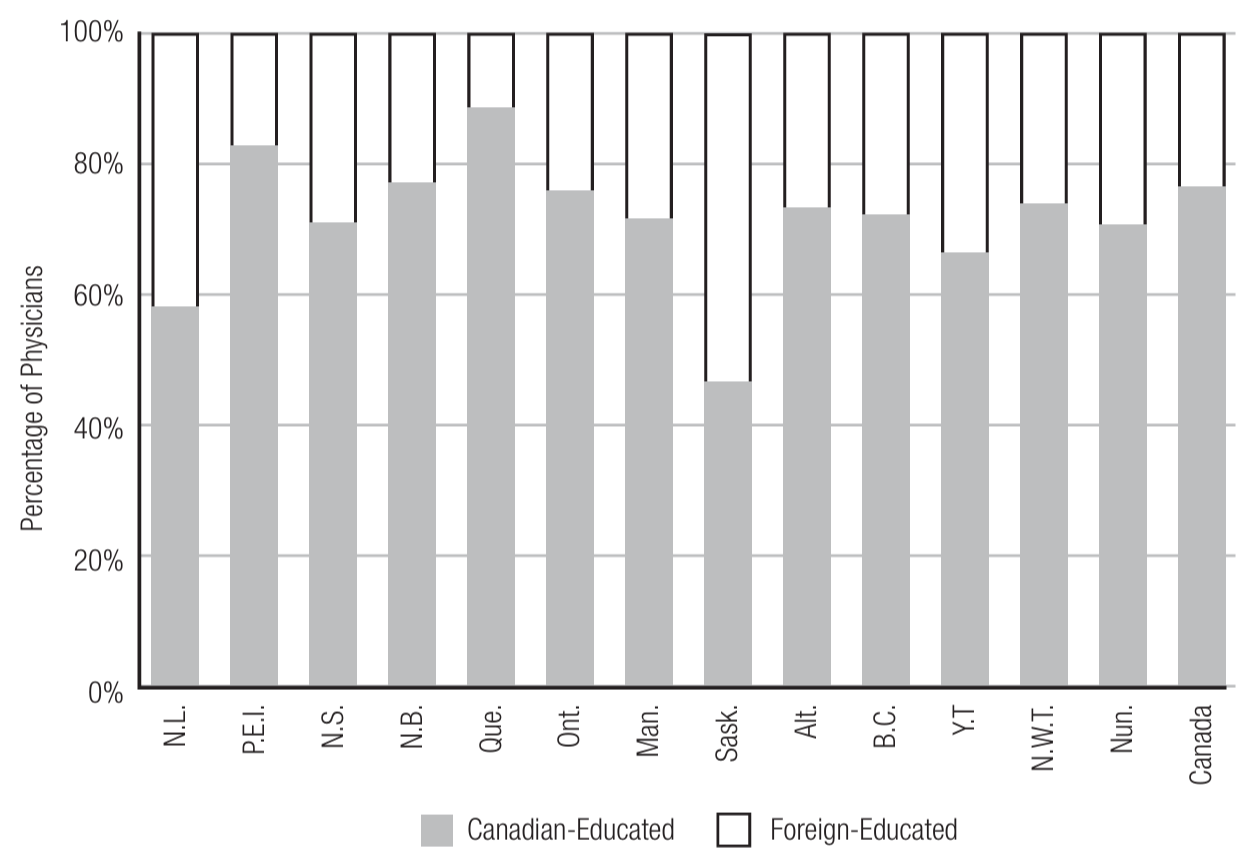

Are requests from whites less readily approved in whiter provinces? In whiter, more traditional provinces, Euro-Canadians may encounter more pushback during the MAID approval process because their physicians are more often of the same cultural background. Although we lack provincial data on physicians by country of birth, we can use the percentage of Canadian-educated physicians as a rough proxy. Unfortunately, the latest figures date from 2004:

Quebec has the highest percentage of Canadian-educated physicians, at about 90%. It also has, proportionately speaking, the fewest MAID requests that actually lead to MAID — many are withdrawn or deemed ineligible, or the requester dies before euthanasia can be provided (Health Canada, 2025, p. 76). Perhaps Quebec physicians are more likely to sit down with the requester and discuss the pros and cons of euthanasia.

Conversely, Saskatchewan has the lowest percentage of Canadian-educated physicians, and its MAID deaths are disproportionately white, surpassed only by Ontario and British Columbia in this regard. Saskatchewan is otherwise more like neighboring Alberta or even Atlantic Canada — comprising mostly small towns, with nonwhites being largely Indigenous people on reserves. Traditional small-town living, in itself, does not seem to protect Euro-Canadians from euthanasia.

If we compare the percentage of foreign-educated physicians with white over-representation in MAID deaths across provinces, we get a modest but non-significant correlation of 0.30. We therefore cannot draw any conclusions about this factor, although it deserves further study with better and more recent data.

Discussion

MAID was legalized in Canada as a human right, that is, everyone has the right to choose the time and place of their death. Nonetheless, this choice — and its subsequent approval — should be viewed within a broader context.

In general, the more freedom physicians have to authorize MAID deaths, the more such deaths become disproportionately white. Specifically, this happens:

when approval isn’t subject to review (currently, all cases)

when no medical justification is needed (Track 2 cases)

when the requester is kept in an institution

when the requester and the physician are not bound by a shared culture and religion

when the broader ideological environment permits anti-white bias

It would be politically easier to say that Euro-Canadians are over-euthanized because they want to be. They are less traditional than other groups, more solitary and thus more open to euthanasia when old age creeps up on them. Yet this explanation doesn’t fit certain patterns in the data.

First, euthanasia is most often preferred at home and as a means to hasten natural death. We see the opposite pattern, however, with white over-representation in MAID deaths. The reason does not seem to be personal choice, at least not by itself.

Second, MAID deaths are disproportionately white in institutional settings — so much so, that this one factor may explain most of the white over-representation. The “home turf” of a private residence or a retirement home seems to offer seniors more freedom to make up their mind — and not have it made for them.

Finally, there are the interprovincial differences: in whiter and more traditional provinces, Euro-Canadian seniors are euthanized at the same rate as other seniors, perhaps even at a lower rate. This might reflect personal choice, that is, a more conservative attitude toward euthanasia among traditional Euro-Canadians. But how do we explain the exceptions of Alberta and Quebec?

Alberta is the province where whites are the least over-represented in MAID deaths and may even be underrepresented. Yet it is not much whiter than Ontario, and almost half its residents are born elsewhere. Nor is it very traditional, at least if we use religion as a metric.

Quebec is the province where whites are the second-least over-represented in MAID deaths, and yet institutional resistance to euthanasia is almost absent there. In addition to having more unique MAID practitioners than all other provinces combined, it has the lowest percentage of hospitals that report no MAID deaths on their premises. Nor is there much resistance from organized religion.

However, Alberta and Quebec are similar in one respect: their estrangement from Canadian political culture. For different reasons, neither province feels wholly part of Canada, and neither feels bound by the country’s current political culture, including the belief that anti-white bias is normal and justified.

Is wokeness a factor? Woke ideology does seem to play a role: the more prevalent it is, the more euthanasia is disproportionately white. This factor is noticeably less prevalent in French Canada, apparently because of the language barrier, the existence of separate institutions and a general mistrust of Canadian political culture. An analogous mistrust may have had similar consequences in Alberta.

In the rest of English Canada, wokeness seems much more prevalent, even more so than in most of the United States. In a sense, English Canadians get the worst of both worlds: they easily absorb American culture but possess none of the immunity to its worst aspects that Americans have acquired to varying degrees.

Yet this is not the whole story. According to a recent report from the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, Canadians aren’t more woke than Americans; In fact, public opinion on cancel culture, critical race/history, and transgender issues is almost the same in Canada, the UK and the US.

But the report does reveal two differences: Although younger people are considerably more woke in Canada than older people, the generation gap isn’t as large as in the UK or US; and Canadians are much more trusting of journalists than Brits and Americans (Kaufmann, 2024). Both findings indicate a higher level of group conformity.

In general, Canadians are less confrontational and more deferential, especially toward representatives of authority, such as government officials, university professors, church leaders and journalists (Lipset, 1986). Once these authority figures have been ideologically captured, everyone else falls into line (Kaufmann, 2024, pp. 61-63). Canadians may feel unhappy about the woke revolution, but they generally keep their unhappiness to themselves.

This reluctance to disagree with authority is reinforced by the fear of job loss and reputation loss (Kaufmann, 2024, pp. 38-44). The same report found that “55 percent of Canadians say they feel less free than they did 5 years ago to express their views on immigration; 61 percent say that the political climate prevents them from expressing their views as it might offend others; and 78 percent say political correctness has gone too far” (Kaufmann, 2024, pp. 38-39).

Canadian deference and non-confrontation may also help wokeness spread within the country’s institutions, which have adopted woke discourse more readily than their American counterparts. Another factor is that Canada’s elite is smaller, more centralized and more interconnected (Brodie, 2001; Clement, 1975; Savoie, 1999). Because Americans have a larger, less centralized and less interconnected elite, on top of being less deferential and more confrontational, they have had less trouble pushing back and building anti-woke institutions.

French Canadians and Albertans seem to be just as deferential and non-confrontational as other Canadians, but they have less trust in the federal government (Leger, 2025). They are thus more likely to challenge wokeness, which has become identified with federal policies.

French Canadians also diverge from other Canadians on certain issues. While they lean further left on economic and foreign policy, in addition to being more republican and anticlerical, they are less woke than English Canadians on gender and racial diversity. In particular, they are more opposed to measures for racial or gender diversity at university, and to transgender rights and flying the pride flag on public buildings. In sum, French Canadians are generally further to the left, but their leftism is much more pre-woke (Kaufmann, 2024, pp. 36, 49).

To what extent does wokeness, in relation to other factors, explain white over-representation in MAID deaths? Can we parcel out the relative importance of each factor? The question is difficult to answer because the different factors interact.

Take the fact that whites are not over-euthanized in Quebec. Is the main reason the lower prevalence of wokeness? Or is it the language barrier, the existence of separate institutions or the lower percentage of foreign-educated physicians? There is no easy answer because these factors are entangled with each other. The French language has hindered the inflow of woke ideology while leading to the creation of separate institutions and a political culture that favors the training of local physicians, rather than the licensing of foreign ones.

Whatever the cause or causes of white over-representation in MAID deaths — woke ideology, contemporary Anglo culture, white individualism, lack of rapport between immigrant physicians and Euro-Canadians — MAID could be the tip of the iceberg. The anti-white bias we see in medically assisted death is probably just as present whenever and wherever a Canadian physician has to make life-or-death decisions.

Peter Frost has a PhD in anthropology from Université Laval. His main research interest is the role of sexual selection in shaping highly visible human traits. Find his newsletter here.

Become a free or paid subscriber:

Like and comment below.

References

Brodie, I. (2001). Interest group litigation and the embedded state: Canada’s court challenges program. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique, 34(2), 357-376. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423901777931

Clement, W. (1975). The Canadian Corporate Elite. McGill-Queen’s University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qf2rw

Cornelissen, L. (2021). Religiosity in Canada and its evolution from 1985 to 2019. Insights on Canadian Society, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2021001/article/00010-eng.htm

Hahn, R. A., Wetterhall, S. F., Gay, G. A., Harshbarger, D. S., Burnett, C. A., Parrish, R. G., & Orend, R. J. (2002). The recording of demographic information on death certificates: a national survey of funeral directors. Public Health Reports, 117(1), 37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4598716

Health Canada. (2025). Sixth Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/health-system-services/annual-report-medical-assistance-dying-2024.html

Kaufmann, E. (2024). The Politics of the Culture Wars in Contemporary Canada. Macdonald-Laurier Institute, February. https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/20240129_Culture-wars-Kaufmann_PAPER-B-v2-FINAL.pdf

Leger (2025). Trust in Government and Views on Provincial Sovereignty, May 12. https://leger360.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Special-report-May-20th.pdf

Lemmens, T. (2025). What Ontario MAID Death Review Committee reports tell us about Canada’s MAID policy and practice—and about the overhaul it needs. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, 8(4), 88-94. https://doi.org/10.7202/1121339ar

Lipset, S. M. (1986). Historical traditions and national characteristics: A comparative analysis of Canada and the United States. Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers canadiens de sociologie, 113-155. https://doi.org/10.2307/3340795

McGivern, L., Shulman, L., Carney, J. K., Shapiro, S., & Bundock, E. (2017). Death certification errors and the effect on mortality statistics. Public Health Reports, 132(6), 669-675. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354917736514

Savoie, D. J. (1999). Governing from the Centre: The Concentration of Power in Canadian Politics. University of Toronto Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442675445

Statistics Canada. (2025). Sources of income of racialized individuals 65 years and over in Canada, 2020. Dorcas Hindir (author). Ethnicity, Language and Immigration Thematic Series, 89-657-X2025003. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-657-x/89-657-x2025003-eng.htm

Statistics Canada (2026a). Indigenous identity population by gender and age: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomeration. Table: 98-10-0292-01. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810029301

Statistics Canada (2026b). Visible minority by gender and age: Canada, provinces and territories. Table: 98-10-0351-01. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810035101

The report states that “There were 298 cases where the postal code was incomplete or incorrect” (Health Canada, 2025, p. 70). This does not explain the discrepancy of 1,011 cases between the Euro-Canadian total of 15,226 on page 32 and the Euro-Canadian total of 14,215 on page 80. The use of the word “incomplete” instead of “absent” may indicate that this file had already been purged of cases with blank address fields.

I asked Health Canada about this discrepancy and was told: “We are looking into the discrepancy you have pointed out and will follow up as soon as possible.” Despite a reminder email, I have received no further communication from Health Canada.

On this point, a recent study of death certificates in Vermont concluded: “Certificates for deaths in hospitals were more likely to have major errors than certificates for deaths in a private residence … Certificates indicating deaths in a nonhospital facility were also more likely to have major errors than certificates indicating deaths in a private residence” (McGivern et al., 2017; see also Hahn et al., 2002).

Another factor may be the difficulty in getting access to euthanasia. Alberta has the second-highest rate of MAID recipient transfers to another hospital (73.6%), a practice usually due to the original hospital refusing to be a party to medically assisted death. Hospital staff may thus do more to talk requesters out of euthanasia (Health Canada, 2025, p. 64).

On the other hand, Manitoba has an even higher rate of MAID recipient transfers (77.3%) and yet its whites are fourth-most likely to be euthanized compared to other groups. And how do we explain Quebec? It has the lowest rate of MAID recipient transfers (4.2%) and more unique MAID practitioners than all other provinces combined. In 2023, the provincial government legislated to ensure that “palliative care hospices may not exclude medical aid in dying from the care they offer” (Health Canada, 2025, p. 84). Yet it is the province where whites are the second-least likely to be euthanized compared to other groups.

I really think Canada has a MAIDS epidemic

I'm Native American and know of the wildly disproportionate rates of suicide among Native Americans so I looked up the rates among First Nations people in Canada. I was not surprised to learn the suicide rates among First Nations people are approximately three times higher than among non-Indian people. In some tribes, the rate is up to 25 times higher. Since assisted suicide is legal in Canada then are First Nations people also disproportionately represented in that form of suicide? If not then why would a suicidally-prone group not also participate in disproportionate numbers in assisted suicide? Apart from cultural and religious reasons, I immediately thought of one potential factor: lack of access to quality healthcare. So here's a bizarre question to ask: Are white Canadians disproportionately committing assisted suicide because they have better healthcare?