Written by Charles Small.

Why do voting maps of Scotland resemble the country’s Iron Age kingdoms? I first noticed the pattern when reading Jim Wilson’s work mapping the genetic landscape of the British Isles. His team found, by looking at Scots with ancestry from different regions, that the country is still genetically divided along the borders of the old kingdoms of Pictland, Strathclyde and others. Wilson’s genetic map looks strikingly similar to Scotland’s electoral ones.

It’s one thing to not move around much, and who could blame you in that climate, but why would the modern inhabitants of those ancient kingdoms vote the same way? As a part-Scot myself, I’m open to the idea that we’re uniquely tribal savages. Yet there appears to be something driving this that applies far more generally, something that may change how you view the world.

Consider the image below. On the left, you see genetic clusters corresponding to the ancestral homes of those who volunteered their genomes for study. On the right are the results from a UK parliamentary election.

A keen eye will notice that the various clusters tended to choose different parliamentary parties from their neighbouring clusters. This pattern has held true over time, even after the rise of the Scottish National Party. To investigate it, I matched each constituency to the relevant genetic clusters. By pooling data from 28 general elections in Scotland over 1918–2019, I found that up to half of the variation in party support was between the clusters (without adjusting for potential confounders). Clusters also tended to vote differently to their neighbours, regardless of the party in question.

This phenomenon is visible on a wider scale. Stephen Leslie and colleagues’ genetic map of the UK, based on DNA from Brits with four grandparents from a particular area, closely resembles the 2017 electoral map—and many others before and since.

Northern Ireland is of course known for its sectarian conflict, and the division of votes along ethnic lines is not surprising there. Such division is not consciously practised in the rest of the country. Yet here it is, in plain view.

Staunchly Labour-voting North West England is revealed to be inhabited by a genetic cluster distinct from the Tory-voting Home Counties in England’s Southeast. Likewise, Northumberland maintains itself as distinct both politically and genetically. While the sample for Brighton was small, Leslie and colleagues’ study picked up a Devonian cluster around the city, which prides itself on voting Green as distinct from the traditional conservative heartland surrounding it. The Cornish independent streak is visible on older electoral maps, but its relative absence in more recent general elections has coincided with increased settlement of English internal migrants, reinforcing the idea that voting still occurs along genetic lines.

Bring back biology

The most parsimonious explanation for this phenomenon is that tribalism is rooted in our biology. Culture, economics and all political science are determined by the limits set by the harder sciences. To study human behaviour, we must understand humans.

Like other creatures, humans have evolved to favour genetic relatives as well as our own individual interests. There is a simple logic to this: a gene for helping one’s relatives can be favoured by selection even if such helping is costly to oneself, since the gene is likely to be present in one’s relatives too—and is therefore “helping” copies of itself. The geneticist J.B.S. Haldane captured this idea in his quip that he would lay down his life “for two brothers or eight cousins”.

This logic of genetic altruism also holds for groups of more distantly related individuals, though the precise mechanism by which this happens is still debated. Due to the influence of genes on phenotypes, genetically similar people may unconsciously recognise each other as part of an in-group, without having to acknowledge a shared identity. Similarity to oneself can function as a cue of kinship—and therefore with whom to form political alliances. After a certain point of relatedness, however, the signal of someone being a distant cousin becomes so weak that our formation into distinct groups must be driven by social forces (which may reinforce kin-selecting mechanisms).

When it comes to more distant relatives, rather than laying down their lives, individuals may make relatively minor sacrifices, such as choosing a candidate favoured by the extended kinship group. Ethnic nepotism in voting could be a manifestation of the same biological mechanisms that give rise to altruism among close relatives, at least in part.

When applied to politics and warfare, this approach could be termed “kinship realism”. In international relations theory, realism purports that nation states act independently in their own self-interest, forming and dropping alliances as they see fit. It seems to me that kinship groups also act in this manner, sometimes prioritising their “genetic interests” above those of their countrymen from rival clusters.

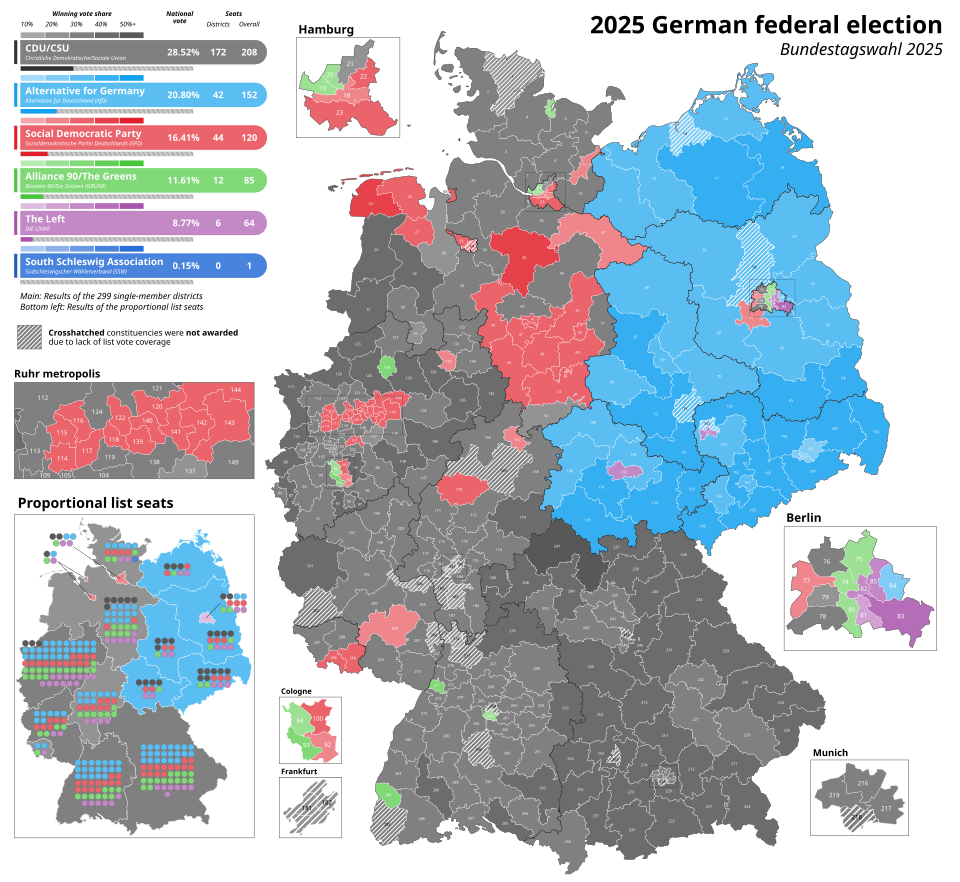

Let’s apply kinship realism to one of the great political issues of our day: the rise of the German “far-right”. As in Scotland, voting appears to be correlated with ancient political boundaries. The much-maligned Alternative for Germany (AfD) does well in the historically Slavic regions of East Germany.

The lands formerly inhabited by the Obodrites, Sorbs and Veleti still contain direct descendants of those tribes. And the genetic signal of those ancient Slavs is present more in East Germans today, even outside of the modern Sorbian population that maintains a distinct language and culture. Simply put, kinship realism would predict that East Germany should vote distinctly to the rest of Germany. Indeed, the rise of the “far-right” appears to be the rise of Slavic Germany and is limited to its traditional homelands.

Genetic politics and warfare

It is possible to measure how far apart European groups are genetically. Analysing the German case further by plotting the Global25 genetic coordinates of East Germans and groups with nearby origins, the Euclidean distance between East Germans and their compatriots in the West is further than that between East Germans and Czechs, a neighbouring Slavic group.

Quantifying things raises questions of what to control for. Waldo Tobler’s first law of geography states that near things are more related than distant things, so genetically closer peoples should, all else equal, be geographically closer. Yet in this case, there is more relatedness than what would be expected from geographical proximity alone. With a shared Western Slavic inheritance, East Germans are closer to Czechs than Hamburg Germans are to Danes.

There is also the issue of past political divisions causing the clusters to remain distinct. Stalin, for example, justified his annexation of Poland in 1939 by claiming it was to protect ethnic minorities, so genetic distinction was the reason for a political division that further impacted genetic differences. After the war, Stalin also happened to occupy German territory along a distinctive ethnic boundary. Reasons of military expediency may explain why the Soviets focused their efforts on taking the Slavic areas of Germany and thereby creating East Germany, but this pattern of wars being fought over the territories of distinct genetic clusters does seem to recur throughout history. Those who only partially conquer a closely-related cluster seem destined to fight in never-ending wars of unification along their artificially imposed frontier.

Prussian General Clausewitz famously said that war is the continuation of politics by other means, and it does appear that warfare follows the same logic of kin preference. To investigate this, I researched the family histories of over a thousand leaders of 654 wars from 1816 to 2007, each one listed in the Correlates of War dataset. I gave each of these leaders genetic PCA coordinates based on the Global25 coordinates for ethnicities of their ancestors. For many, this entailed going back to the medieval period, while for others an estimate had to be made due to the paucity of publicly available genealogical information.

My key finding was that allies tend to be genetically closer to each other than adversaries. For example, the genetically closest living other leader to former British Prime Minister Tony Blair in the dataset is former US President George W. Bush. Unsurprisingly, they are much closer than their adversaries Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden. Considering that wartime allies Blair and Bush were born an ocean apart illustrates that ancestral genetic proximity can matter more than geographic origin in the traditional sense (London being closer to Baghdad than to Washington D.C.)

In the over 3,000 relationships between wartime leaders sampled, adversaries were over 10% further away by Euclidean distance in PCA space than allies, and this increased further after statistical adjustments. Overall, adversaries were about as genetically distant as an East German and a Turkman, while allies were about as close as an East German and a Lithuanian.

Can it all be culture?

For many of us who have sunk years into studying politics and international relations, it is tempting to fall back on the old explanations for this phenomenon. Perhaps it’s all culture. Shared symbols, a tradition of speaking the same language, economic integration and traditions of democratic governance are meant to explain the close Blair-Bush alliance. And democratic peace theory teaches that democracies don’t go to war with each other.

There is undoubtedly some truth in these explanations, but to neglect the genetic relatedness of those with real military power in democracies is a mistake. As with the ethnic voting blocs in which customs, dialects, names and other markers of in-group identity reinforce kin-selecting mechanisms, cultural norms of democratic institutions could be seen as an emergent phenomenon arising to promote kin selection at scale (though this is, admittedly, speculative).

The concepts surrounding kinship realism were so embedded in international relations historically that it was taken for granted that alliances would be forged through intermarriage of royal families. Such intermarriage eventually led to what was effectively ethnogenesis: the creation of a new genetically distinct people group. By plotting the genetic coordinates of the ancestors of Europe’s aristocracy and royalty from the late medieval period, it was possible to see that the European elite did not clearly belong to any national genetic cluster. Much as India’s caste system can be viewed either through a Marxist lens of class oppression or an ethnographer’s lens of distinct people groups competing with one another, so can Europe’s modern history.

Most elites who historically ruled the British Isles, for example, are deeply admixed with the European aristocracy and royalty cluster, maintaining a social system that benefitted those genetically closer to them than the average Englishman, consistent with the logic of kin preference. This is the case to a much lesser extent today, though Blair for example is part-descended from this European aristocratic cluster.

Analysing distinct cultural groups like these has been a part of modern intelligence gathering since its early post-World War II days. The now public Central Intelligence Agency archive is full of reports discussing the cultural practices of various peoples involved in conflicts around the world. With the advancement of modern genomics, intelligence agencies would benefit from including genetic distance calculations in their toolkits to help prevent wars that could affect the rest of us.

By taking into account genetic distance, kinship realism has the potential to revolutionise how we view history and modern society. It will never offer a complete explanation, but it can still be valuable. Across time and space, human relations are shaped by genetic proximity. We are, after all, an advanced ape, and animals in general favour those genetically closer to themselves.

Charles Small is data analytics and open-source intelligence consultant. You can follow him on Twitter and Substack.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

AfD electoral success entirely overlaps with the political borders of the former East German state, suggesting its overperformance there is caused by different 20th century sociopolitical experiences and their aftereffects rather than early medieval population history. This can simply be tested by looking at a) parts of former East Germany which didn't have a Slavic population in the early Middle Ages (Western Thuringia, Western Saxony-Anhalt) - AfD does just as as well there as in the rest of East Germany b) parts of West Germany where Slavs did live in the past (East Holstein, Wendland in Lower Saxony, parts of Bavaria along the Czech border) - no particular AfD overperformance there.

Also, when estimating the degree of "Slavicness" of East Germans by comparing them with Czechs it's important to keep in mind that the latter are far more Western-European like genetically compared to other Slavic peoples to the prehistorical and historical population history of the Czech lands. The genetic distance between East Germans and Poles would be considerably larger.