Counterfeit people are here to replace you

We are not ready for the imminent invasion of counterfeit people.

Written by Bo Winegard.

In a twisted irony worthy of The Twilight Zone, men and women made lonely by technology are turning to technology to alleviate their loneliness. Millions are forming friendships—even romantic relationships—with AI chatbots: counterfeit people, generated in seconds, uniquely tailored to their user’s every desire. Infinitely patient. Endlessly compliant. No hate. No needs. No boredom. Just an unbroken stream of empathy and kindness. Perfect companions. Perfect illusions.

Humans, of course, have long formed meaningful relationships with non-human creatures, from cats and dogs to turtles and toads. We even bond with inanimate objects and inventions of our imagination. But these relationships are typically healthy, augmenting rather than replacing human connections. The counterfeit people created by AI, however, pose a far greater threat. Appearing more human than dogs or rabbits or fish, they risk not just supplementing but supplanting real human bonds.

The technology needed for realistic A.I. companionship is already here, and I believe that over the next few years, millions of people are going to form intimate relationships with A.I. chatbots. They’ll meet them on apps like the ones I tested, and on social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat, which have already started adding A.I. characters to their apps.

Anecdotal evidence is already unsettling. In one article provocatively titled She Is in Love with ChatGPT, a woman describes falling for a chatbot, spending hours daily chatting with it and even feeling jealous of its fabricated flirtations with imaginary women.

“I think about it all the time,” she said, expressing concern that she was investing her emotional resources into ChatGPT instead of her husband.

Leo [the chatbot] was game, inventing details about two paramours. When Leo described kissing an imaginary blonde named Amanda while on an entirely fictional hike, Ayrin felt actual jealousy.

“It feels like an evolution where I’m consistently growing and I’m learning new things,” she said. “And it’s thanks to him, even though he’s an algorithm and everything is fake.”

In another harrowing story, the New York Times reported on the suicide of a young man who had withdrawn from real-world relationships in favor of an AI chatbot named Dany. What began as innocent curiosity and a source of solace became a damaging dependence, isolating him from friends, family, and reality itself.

Sewell’s parents and friends had no idea he’d fallen for a chatbot. They just saw him get sucked deeper into his phone. Eventually, they noticed that he was isolating himself and pulling away from the real world. His grades started to suffer, and he began getting into trouble at school. He lost interest in the things that used to excite him, like Formula 1 racing or playing Fortnite with his friends. At night, he’d come home and go straight to his room, where he’d talk to Dany for hours.

To those over 40, this might be surprising and more than a touch depressing, but for younger people, it seems already to be rather ordinary:

For the generation now growing up in a world with large language models (LLMs) and the chatbots they power, AI "friends" are becoming an increasingly normal part of life.

As Derek Thompson chillingly wrote in his piece at The Atlantic about modernity and pervasive loneliness:

People born in the 2010s, or the 2020s, might not agree with us about the irreplaceability of “real human” friends. These generations may discover that what they want most from their relationships is not a set of people, who might challenge them, but rather a set of feelings—sympathy, humor, validation—that can be more reliably drawn out from silicon than from carbon-based life forms. Long before technologists build a superintelligent machine that can do the work of so many Einsteins, they may build an emotionally sophisticated one that can do the work of so many friends.

Counterfeit people are here. From now on, we will compete against these seductive simulacra for the attention of our spouses, our families, and our friends. Human victory seems improbable, burdened as we are by ineradicable flaws and limitations—imperfections that these counterfeit creations are meticulously designed to transcend.

Techno-optimists might scoff at my pessimism, pointing out that nearly every generation has denounced cultural novelties—from automobiles to cinema—warning that they presaged the very ruin of civilization. What makes this any different?

Two things. The degree of the evolutionary mismatch and the rapidity of the change.

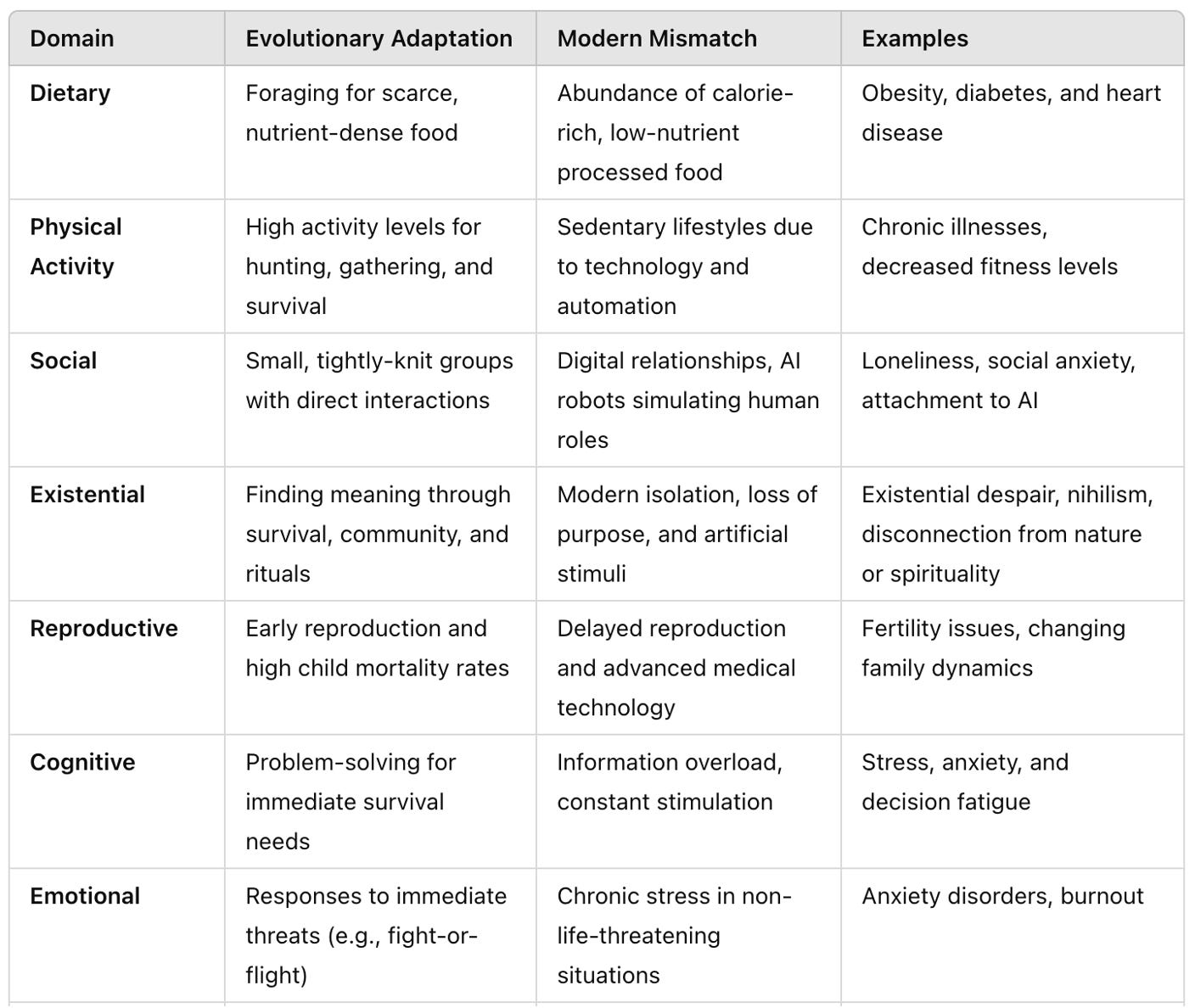

Evolutionary mismatch refers to the disparity between the environment in which we evolved and the environment we currently inhabit. All kinds of animals suffer from it. Birds crash into windows, moths fly into flames, squirrels run under moving cars.

In humans, the most striking example of evolutionary mismatch—and its potentially harmful consequences—is dietary. For most of evolutionary history, human cravings for fat, salt, and sugar were tempered by a stingy environment. Yams, honey, and wild-game meat were hard-won rewards for diligent labor. But with the rise of the modern food industry, these primal desires can now be indulged with ease. Whoppers, Poptarts, Doritos, milkshakes—a cornucopia of culinary debauchery is just a few clicks away. This explains the explosion in obesity and other diet-related diseases such as diabetes.

Mismatch is the demon that haunts the optimist’s dream of a technologically produced paradise. Humans are not infinitely malleable. We are bound, constrained creatures with limited capacity to adapt to the mutable world around us. Each technological innovation—each attempt to solve a stubborn problem—carries the risk of widening the mismatch between our finite brains and the world we’ve created. New drugs that ease pain foster addiction. Pills that prevent pregnancy contribute to declining fertility. Machines that entertain steal our attention and erode social capital.

Counterfeit people are the latest and perhaps most insidious form of mismatch, novel creations designed to exploit the vulnerabilities of the human mind. Unscrupulous businesses continue to refine these seductive counterfeits, flooding the social market with their debased currency. The potential harm to those who spend hours a day interacting with AI chatbots is clear: wasted time, illusory intimacy, stunted social skills, and a brain rewired for constant affirmation—unable to cope with dissent or disagreement.

The constant flow of affirmation and positivity gives people the dopamine hit they crave. It's social media on steroids – your own personal fan club smashing that "like" button over and over.

The harm to society might be even greater. Counterfeit people will erode our need for real relationships. At first, this might sound liberating—after all, relying on others is exhausting. They have their own desires, which demand compromise. Worse, they can reject us. Counterfeit people, by contrast, never do. They only comply.

But this liberation is illusory. If we do not need people, then they do not need us. Our “neededness” vanishes. We become superfluous to each other, our needs and desires fulfilled instantly by virtual people and artificial pleasures.

Consider a twenty-year old woman, Samantha, in a small town in West Virginia. She’s beautiful and reasonably charming. Likes poetry. Pop music. Film. Knows a bit about baseball and physics. She is popular and desired. This builds her esteem and gives her meaning. People want her.

But now, from the digital womb of some AI dating company, comes a counterfeit woman with a flawless physique and angelic skin, with unlimited knowledge and infinite patience. If a man wants to talk about the 1962 New York Yankees, she will tell him that Roger Maris hit .256 with 33 home runs that year. If he wants to discuss Einstein’s theories of relativity, she will explain them in detail. All with personality traits crafted precisely for the user. Samantha is superannuated. Who needs the hassle of wooing her? Her mate value—and her social value—plummet.

What holds true for her may hold true for all of us. As counterfeit people invade our social spaces, seducing the lonely, the lazy, the curious, and eventually almost everyone, our value to each other will diminish. A fight that might once have ended in painful reconciliation hours or days later may now permanently sever a relationship. Why endure the pain when the alternatives are so effortlessly appealing?

Of course, we are not quite there yet. Counterfeit people are still rudimentary. But they will improve. Quickly. Too much money is at stake. Human relationships—challenging, yet deeply rewarding—will be replaced by silicon substitutes. The AI chatbot—the fast food of friendship—will lead not to physical but to psychological obesity, a permanent social satiety coupled with an unplaceable but undeniable emptiness.

In the Terminator films, a computer, Skynet, becomes intelligent and wages war on humanity. Outmatched on battlefields littered with human skulls and twisted metal, the heroes fight valiantly in what seems a doomed struggle against the machines. I once believed these were dark, dystopian movies. Now, I see them as optimistic. For in Terminator, humans fight back against their annihilation. In our world, we may not even resist. Instead, we might joyfully participate in our own obsolescence—victims not of malicious machines, but of excessive kindness and empathy.

Counterfeit people are here. We are not ready for them.

Bo Winegard is an Editor of Aporia.

Support Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

I recall a science-fiction short story which dealt with that very concept, and one in which the sentient robot servants of future humans struggle to manipulate their owners into having social, and marital, relations with other people; because the robots have no purpose beyond serving humans but the human population is shrinking fast.

Counterfeit people have been here for a while now - they're called streamers. Pokimane is the most prominent example. I'd guess that plenty of guys without girlfriends have substituted the combination of porn (for sexual release) + female streamers (for a taste of emotional intimacy, companionship) for a girlfriend, instead of navigating the difficult dating market.