Africa is not doomed to poverty

There are factors well known to economists – but not to the general public – that can explain why African development has stalled.

Written by Simon Laird.

There is a tendency among those who believe in biological race differences to believe that such differences are the only explanation for poverty in Africa, and that Africa will therefore always be poor. This view was put succinctly by the co-discoverer of DNA, James Watson, who said that he was “inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa” because “social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours – whereas all the testing says not really.”

Watson’s conclusion, that there is no hope for development in Africa, does not actually follow from the premise. Let’s suppose for the sake of argument that race differences in intelligence are largely attributable to genes. It still would not follow that Africa is doomed to poverty. There are factors well known to economists – but not to the general public – that can explain why African development has stalled.

Consider this argument:

Premise 1. Economic development begins in one place and then spreads out geographically. Modern economic development began in England around 1650 and then spread to Western Europe and England’s colonies, followed by Eastern Europe and Japan.

Premise 2. In the 20th century there were a series of events that severely hampered the spread of economic development.

Conclusion. Since economic development had not yet spread to Africa when these events unfolded, Africa remains far below its potential.

Diffusion of Economic Development

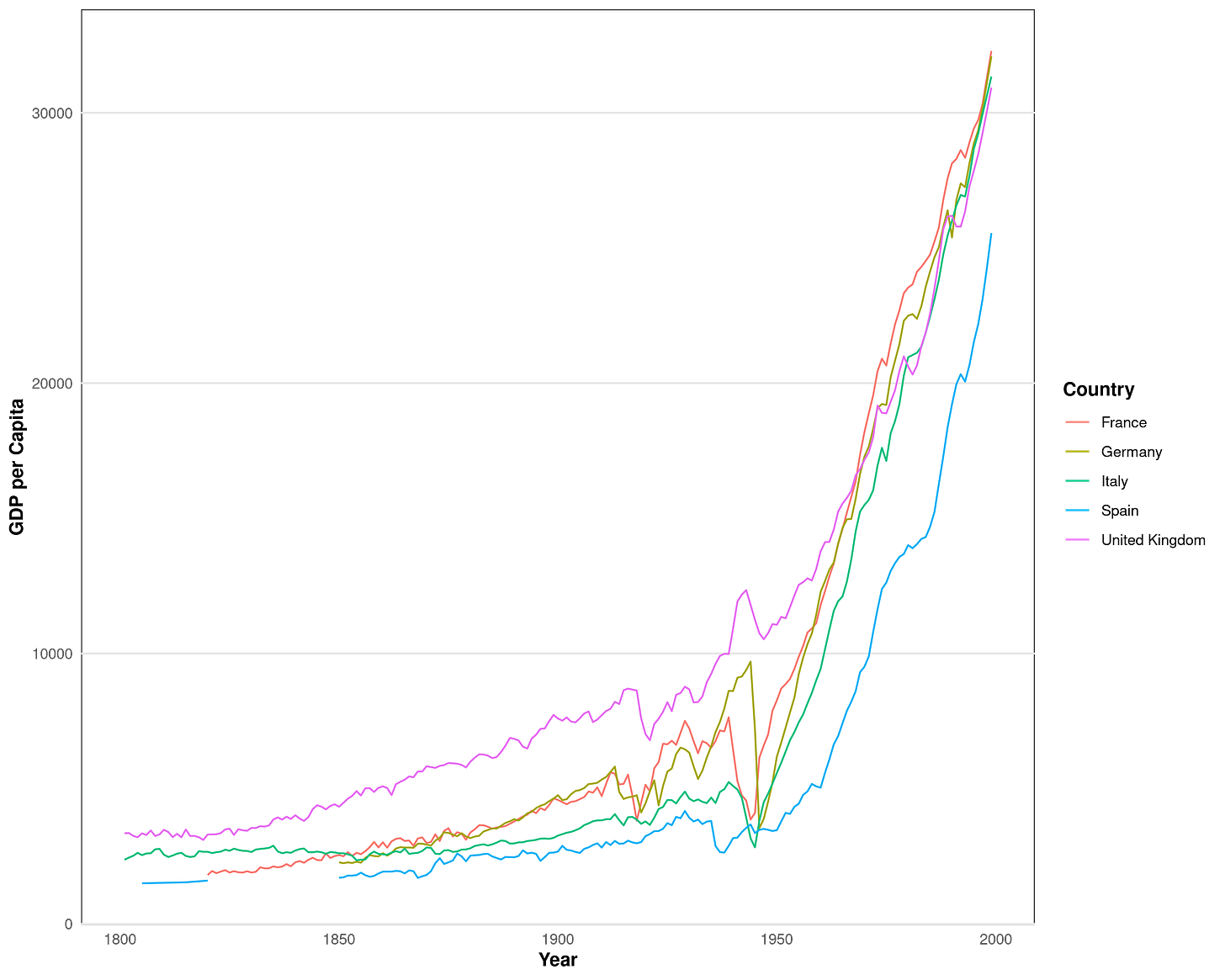

The fact that economic development begins in one place and then spreads out geographically is well accepted by economists. It is abundantly clear in the historical data on economic growth. The gold-standard dataset on historical growth comes from the late Angus Maddison and the Groningen Growth and Development Centre. The graph below shows per capita GDP for selected Western European countries from 1200 AD to 1900 AD.

In 1300, Western Europe had a GDP per capita of about $1500 (in inflation adjusted 2011 dollars), which was similar to the region’s GDP per capita in the year 1 AD. Living standards were low and stagnant for a very long time. Then around 1650 something happened in the United Kingdom and living standards began to grow exponentially. Economic historians have spent thousands of man-hours studying 1600s Britain, trying to figure out what exactly went right. The answer has at least something to do with the Glorious Revolution, England’s Parliamentary restraints on the monarchy, and the resulting friendliness to free-market policies. I will call this transition from long-standing stagnation to modern exponential growth the “Development Revolution”.

By around 1820, the Development Revolution had spread to France and Germany – though they were still poorer than the UK in 1900 because their development had started later. However, there are theoretical reasons to expect countries that start growing later to grow faster and eventually catch up with countries that started growing earlier. Here is the argument:

Production is done by workers (labour) who use tools and machines (capital).

When the quantity of workers is high and the quantity of capital is low, the marginal value of one more unit of capital is high. When the quantity of workers is low and the quantity of capital is high, the marginal value of one more unit of capital is low.

Hence in countries that have already had a lot of growth, the marginal value of capital is low (because there is already a lot of capital relative to the number of workers). But in countries that have just started to grow, the marginal value of capital is high (because there are many workers and not much capital).

Hence capital will get a higher return in poorer countries. So investors will want to invest their capital in the less developed countries rather than the more developed ones.

Hence capital will flow from the more developed countries to the less developed ones until the capital/labour ratio between them is roughly the same.

This textbook economics argument has been borne out in Western Europe. Here is GDP per capita for the same set of Western European countries from 1800 to 2000.

By 2000, France, Germany and Italy had fully caught up with the UK, and Spain was not far behind. The name for this phenomenon is “convergence”. Now let’s zoom in on the transition from Early Modern to Modern Europe.

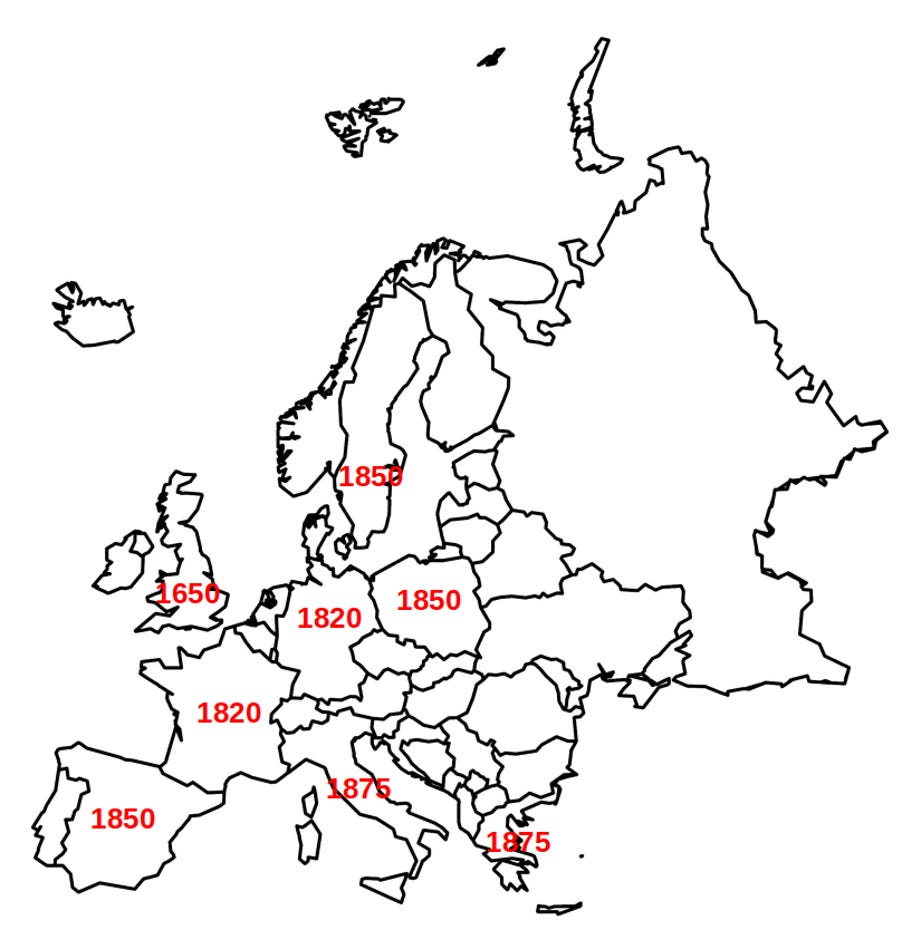

Britain is the leader. After Britain, France and Germany started growing the earliest (about 1820) and by 1913 they are clearly ahead of the rest of continental Europe. Sweden and Poland took off around 1850 and both grew rapidly. Italy and Greece show a trend toward growth around 1875. Spain also started growing around 1850, but did so more slowly than the other countries.

I have labelled this map with the year in which each country embarked upon the path of exponential economic growth. The data are messy but overall a clear pattern emerges: the Development Revolution began in Britain and spread outward from there.

In addition to spreading out geographically into Europe, the Development Revolution spread to England’s offshoots in America and Australia.

Counterfactuals

Imagine a world that has not yet had a Development Revolution. Suppose that each point on Earth has an equal probability of producing one, and once it has occurred economic development will spread outward from that point.

There is one timeline in which the Development Revolution happens in Persia, and then spreads to Pakistan and Arabia. In that timeline, Middle Easterners might have settled the Americas and set up colonies all over the world. Islam rather than Christianity might be the dominant religion. We might be speaking Farsi rather than English.

There is another timeline in which the Development Revolution happens in East Asia. China, Korea and Japan become the world’s three dominant powers. They settle the Americas and rule over Middle Easterners and Europeans. Confucianism reigns.

What stalled development in Africa?

Economic development and technological progress in Europe allowed Europeans to dominate Africa. They brought their technology and their ideas about government, pulling Africa out of the dark ages. Imperial officials and missionaries introduced literacy, modern technology and healthcare, thereby jumpstarting economic growth.

But in the mid-twentieth century African development stalled. Why? It was arguably a combination of factors: fiscal mismanagement, the devastation of WWII, the spectre of communism, and growing anti-colonial sentiment among Western elites. As a consequence, the West gave up its colonies and withdrew the colonial administrators. Civilization went into reverse.

Many post-colonial states fell to warlords or communists. Since most parts of Africa saw economic decline after the colonial period, they were by definition below their potential. Since then, however, some African countries have resumed growth – while others have stagnated.

Let’s examine the trajectory of four countries since the end of colonialism:

Liberia. The country was founded in 1822 by the American Colonization Society, a group that sought to resettle American Blacks in Africa. The colonists were freed slaves. They established a coastal city called Monrovia (named for James Monroe) and extended their rule into the jungle interior of the country. Liberia has been criticized for its corruption and abuses, and for its practice of slavery. Yet every system has some corruption, and Liberia was able to build a more advanced civilization than anything that had existed in Africa prior to European contact.

Although the Liberian settlers (the Americo-Liberians) kept themselves separate from the surrounding African tribes, they established Christian missions in order to civilize the natives and convert them to Christianity. Some Western ideas of human rights appear to have been present. In 1930 the League of Nations published a report claiming that the Americo-Liberians were enslaving some of the natives, and in the ensuing scandal both the President and Vice President of Liberia resigned.

During the 1940s, thousands of uncivilized Africans migrated from the interior of the country to the Americo-Liberian colonies on the coast. The colonists had previously prevented this kind of immigration, but in the 1940s the government “was no longer able to restrain it”. Since no country with a functioning military is actually “unable” to prevent migration, we should infer that the government was unwilling to stop immigration, presumably due to the kinds of sentiments expressed in the League of Nations report.

In 1980 master sergeant Samuel Doe, from one of the indigenous ethnic groups of the interior, overthrew the government in a military coup. Many Americo-Liberians fled the country. Liberia has been a tinpot dictatorship ever since.

Katanga: After the end of Belgian rule in the Congo, the southern province of Katanga declared its independence from the central Congolese government. The President of Katanga was Moise Tshombe – a pro-Western, anti-communist leader. Katanga was supported by both South Africa and Rhodesia, but neither the United States nor the Soviet Union agreed to recognize it. The two superpowers supported the centralized Congolese government and its Communist-aligned leader Patrice Lumumba.

Katanga was better administered and more prosperous than the rest of the Congo. Skilled white technicians supervised large numbers of black factory workers, who made better wages than they would have done anywhere else in the country. With the support of both the US and the USSR, United Nations troops crushed Katangese resistance and forced it back under the thumb of the centralized government in Kinshasa.

According to American anti-communist groups, the UN troops had originally presented themselves to Tshombe as peacekeepers and vowed not to take part in Katanga’s internal affairs. Once they had amassed enough of these “peacekeepers” on Katangese territory, UN forces betrayed Tshombe and attacked, striking both military and civilian targets. The UN also expelled all civil service and military personnel of European descent. (The UN disputes this version of events.)

All sides agree, however, that UN forces attacked Katanga and forced it back under the dominion of the centralized Congolese government. The fledgling state’s infrastructure and industrial capacity was badly damaged by the war and has never really recovered. Today Congo is one of the poorest places on Earth.

Botswana: The most prosperous country in Sub-Saharan Africa is Botswana. In 2022 the country’s GDP per capita (at PPP) was $18,323. By way of comparison, Mexico’s was $21,512. Ukraine had a GDP per capita before the war of $18,040, and the sub-Saharan African average was just $4,639. The average Botswanan is about as rich as the average Colombian and richer than the average Egyptian.

Some hereditarians have dismissed Botswana’s success as the product of its well-run diamond mines. But this begs the question. Since nearly all of Sub-Saharan Africa is rich in natural resources, why does Botswana manage its natural resources competently while other countries do not?

When Botswana became an independent “democracy” in 1966 the voters elected their hereditary king to be their first president. The king had studied at the London School of Economics, and he immediately implemented capitalist policies. Botswana never nationalized its diamond mines and it has an ongoing partnership with the De Beers corporation. Meanwhile, in neighboring Rhodesia, communists took over the country and nationalized the diamond mines. After decades of misrule, Zimbabwe is extremely poor.

Rwanda: The UN famously failed to intervene during the Rwandan genocide of 1994. As a result, the post-conflict government was formed by the victorious Tutsi militia led by Paul Kagame. For several years after the genocide, there were strict curfews every night. Crime is punished swiftly and severely. Citizens are required to participate in neighborhood watch programs. The result has been peace, stability and an economic boom.

Kagame has been President since 2000. Western, “liberal-democratic” globalist organizations are upset with him because he does not allow the masses to vote on whether he stays in power. Identitarians might disapprove of Rwanda’s heavy-handed integrationist policies. Ethnic “divisionism” is illegal and the government operates model “reconciliation” villages in which Tutsis and Hutus are forced to live side by side. But Kagame’s record speaks for itself; he has led his people back from genocide to peace and relative prosperity in a single generation.

Conclusion

In summary, economic development began in England, before spreading outward to continental Europe and England’s colonies. Economic progress would have spread across the whole world (at least to some degree) if it had not been arrested by communism, decolonization, and the West’s loss of self-confidence.

In the four case studies mentioned above (Liberia, Katanga, Botswana and Rwanda) we see evidence that leftist policies like universal democracy, open immigration, anti-colonialism and leniency for criminals are associated with poor outcomes.

The collapse of Liberia was in part caused by anti-civilizational trends that took hold in the West in the mid-twentieth century. Liberia’s was related to its failure to take a hard line on immigration. Katanga was militarily destroyed by the UN. Two of sub-Saharan Africa’s biggest success stories, Botswana and Rwanda did not take the typical “sovereign liberal democracy” path – which the “international community” has tried to force on former colonies. Botswana’s post-colonial government was contiguous with its hereditary monarchy and it implemented capitalist policies. Rwanda has resisted international pressure on law and order, allowing it to remain largely peaceful.

Even if you maintain that genes explain why Africa is relatively poorer than the rest of the world, they cannot explain the absolute level of African poverty. The fact that living standards are absolutely low today has a lot to do with the historical and cultural factors outlined in this essay.

It is the Left that has destroyed the prospects for a reasonable degree of prosperity in Africa. It is the UN – not leaders like Moise Tshombe and Paul Kagame – that has made the Eastern Congo a warring hellhole for the last 60 years. It is the Left that has blood on its hands. A higher standard of living for Africa really is possible… if the Left would just get out the way.

Simon Laird holds a Master's degree in economics from George Mason University and works for a political organization in Washington, DC. He writes about philosophy on his Substack.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.

Everyone needs to examine their biases and prejudices every now and again. So I read your article with interest to examine those within myself. However, I am still not convinced those biases are groundless, or for that matter an irrational prejudice on my part.

Here is my simple rebuttal to your counterfactual (a counterfactual in itself?)—South Africa!

SA was a first world nation when it turned itself over to the Black majority rule in the mid-nineties. I believe they even perfected a nuclear weapon, not to mention the world’s first heart transplant! Heck they gave us Elon Musk to boot. ;-) But that was then and this is now.

In the span of basically a quarter century (the turnover of political authority was staged and took a bit of time), they are a basket case—brownouts throughout the nation, water crises in major cities, farmers being killed in the middle of the night and their farms confiscated, inflation, White dispossession and White homeless encampments, riots and the like. Not to mention politicians running on “kill the Boar” platforms. This “grand experiment” is not yet over. It will become worse and certainly would be had it not been for the few remaining Whites they allow to remain in significant managerial positions within the general economy—this do to law requiring mostly Black hires regardless of merit. We call this here in the States, AA.

If Africa’s problem is less about the general (sub)African’s genetic makeup and more about their peculiar development timing and geographical predicaments, how do we explain SA before and after Black rule as described above? The answer—genetics—both wrt to IQ *and* behavioral proclivities (also tied to genetics). The economists’ excuses notwithstanding, Africa is Africa because of Africans. The experimental result of replacing the SA White controlling population with a Black controlling population is pretty good evidence of this as any measurement and experimental design person will attest to.

Finally, I’ll note that we too in the USA are also partaking in such an SA experiment here at home—only at a much slower rate—as we replace our White heritage population with non-White, diversity. And as we produce a generally lower national IQ, we too will test the limits of our “Smart Fraction” to keep and maintain a first world technological society. That limit is not yet known, but as we approach it, we will see signs—and they won’t be pretty. :-(

Africa is poor largely because of the quality and intelligence level of its inhabitants. What wealth or ‘development’ exists is the result of western or Chinese assistance and direct involvement. The author sounds like another apologist for our current economic and financial system. Africans should largely be left alone by people like the author to develop their own system to the best of their abilities. Africans like Asians will never be white or western. Different peoples different ways and standards. One economic or political model isn’t suitable for all people on the planet.